Cello Artificial Harmonics

WHAT IS AN ARTIFICIAL HARMONIC?

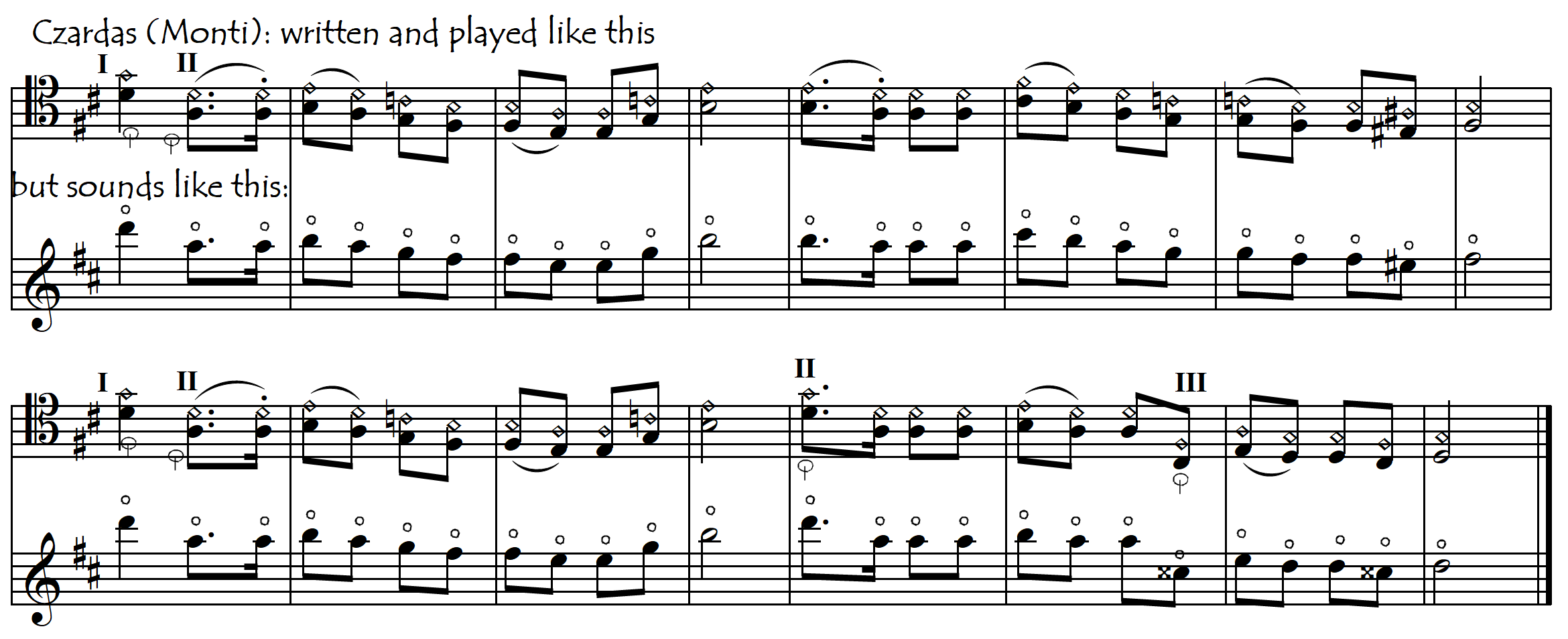

Whereas a natural harmonic requires only one finger touching the string, artificial harmonics require two fingers on the same string simultaneously. The lower finger needs to stop the string firmly, while we simultaneously gently touch a higher finger to the same string. In the most commonly used artificial harmonic the musical distance between the bottom and top fingers is a perfect fourth. This is the standard artificial harmonic interval, indicated by a hollow diamond notehead one fourth above a normal notehead. It gives us a pitch that sounds two octaves higher than the stopped (lower) finger as illustrated in the following example from Monti’s Czardas.

The following link opens up a compilation of repertoire passages using artificial harmonics (and their various substitutes).

Artificial Harmonics: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

USING DIFFERENT INTERVALS ABOVE THE STOPPED FINGER (THUMB)

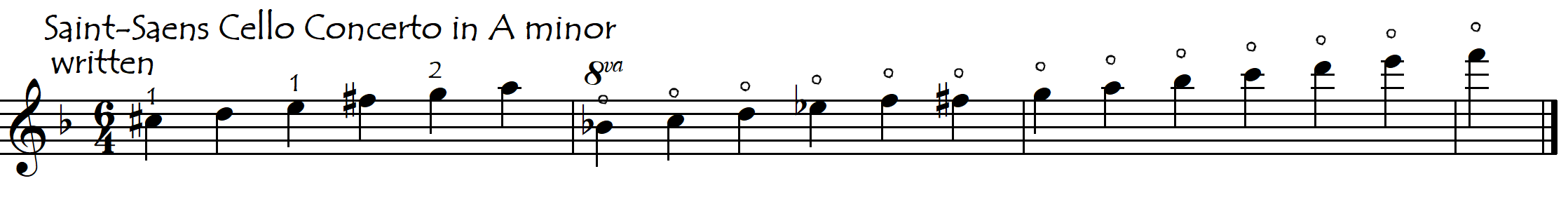

Although the most common interval we use to play an artificial harmonic is the fourth above the stopped finger, we can also use other intervals (and also sometimes natural harmonics). Artificial harmonics also sound on the major third and perfect fifth above the base (stopped) finger. For this reason, composers sometimes notate the harmonics at the sounding pitch and leave it up to the instrumentalist to find the best way to sound (play) them. Let’s look now at these different artificial harmonic fingering possibilities in order of “popularity” (utility).

ARTIFICIAL HARMONICS ON THE FIFTH

The artificial harmonic that is produced when we touch the finger lightly to the string a fifth above the thumb, sounds a note that is one octave above the “harmonic” finger (one octave plus a fifth above the thumb). This artificial harmonic is both easier, safer and more resonant then the one we normally use (on the fourth above the thumb). Try playing some and you will confirm this observation. Why is this ? This added safety, ease and extra resonance are due to the larger distance (a fifth instead of a fourth) between the “stopping” finger (thumb) and the “touching” finger (usually the third finger). The extra length of vibrating string gives simultaneously an added resonance (volume) and a significantly greater margin of error in our thumb-finger relative spacing (before we get that familiar unintelligible squeak).

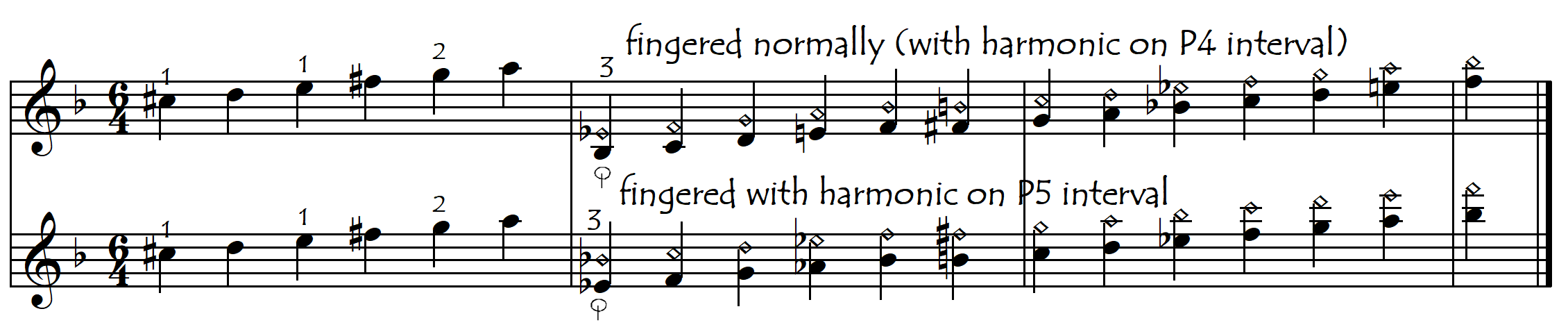

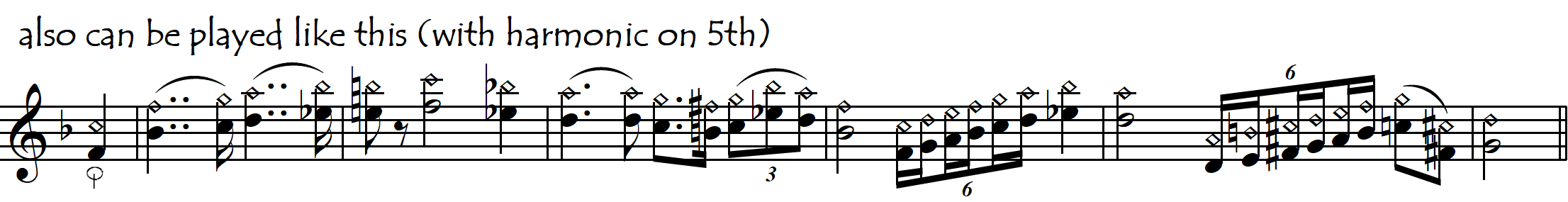

The above example could be perfectly played with either the standard perfect fourth interval or the more unconventional perfect fifth interval between base and harmonic finger:

The added safety, resonance and ease of playing for the harmonic at the fifth may seem surprising as the hand is so much higher up the fingerboard than it would need to be to sound the same harmonic pitch with the “standard” perfect fourth distance between thumb and stopping finger. In fact, with the harmonic at the fifth, the 3rd finger is a full 5th higher up the fingerboard (and the thumb a fourth higher) than it would need to be to sound the same note using the harmonic on the fourth. Normally, the higher we go up the fingerboard, the more dangerous and unstable things get: but not in this case – quite the opposite in fact. This “ease of speaking” and extra resonance means that some artificial harmonic passages (especially the higher ones) that are traditionally played with the “normal” harmonic (on the fourth) might actually be easier using the harmonic on the fifth.

If we want to change from an artificial harmonic on the fourth to playing the same note with an artificial harmonic on the fifth, we simply need to put our thumb where our third finger was, and then reach up a fifth for our “harmonic” finger. In other words, if we place our thumb on the note that was played by the higher finger in the standard “on-the-fourth” artificial harmonic then this puts our hand in the correct position to sound the same note but now with an interval of a fifth between thumb and higher finger. Being aware of this can help us read and play with the “on-the-fifth” hand configuration artificial harmonic passages that are notated for the standard “on-the-fourth” hand configuration. We can see that in the above (and in the following) examples.

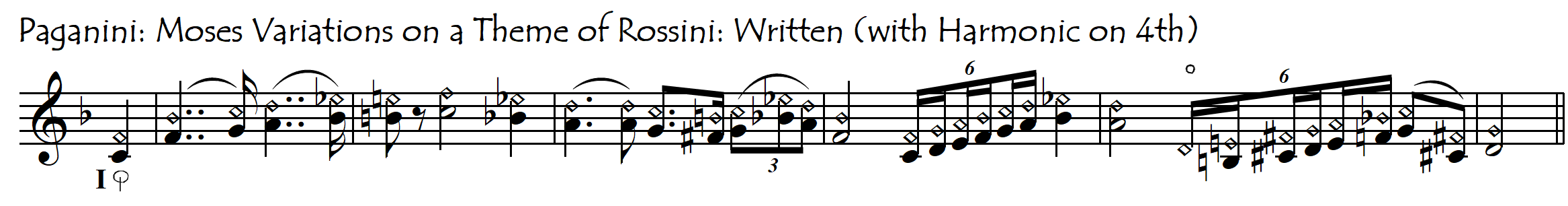

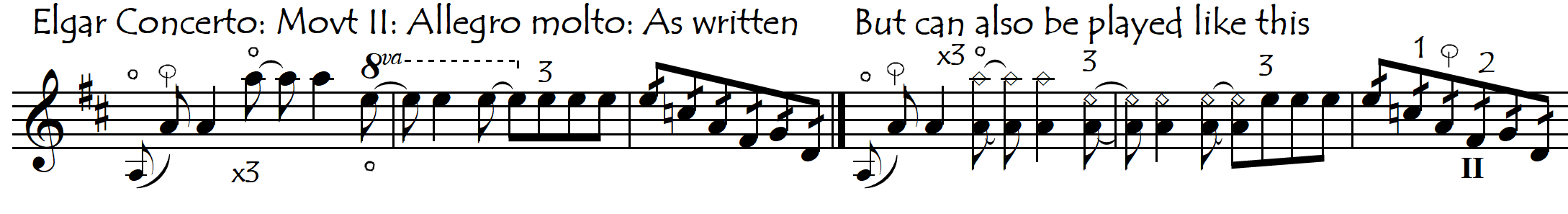

Here is another repertoire example for which we could quite happily substitute the standard fingering for a fingering using the artificial harmonic on the fifth:

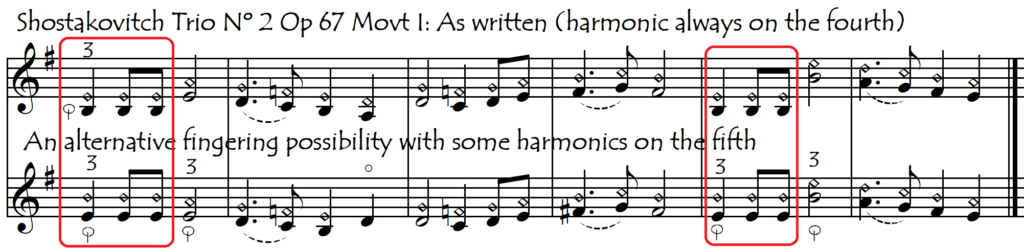

On other occasions, we can mix-and-match our artificial harmonic fingering, for example by using an occasional harmonic on the fifth to avoid a large shift during a passage in “normal” artificial harmonics such as in the following passage from the opening of Shostakovich’s Trio nº 2

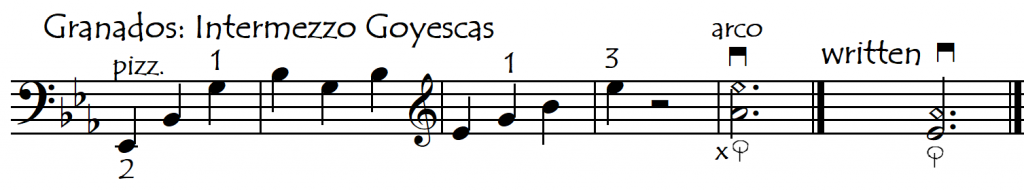

Sometimes an isolated use of this harmonic avoids shifting entirely, thus giving greater intonation security:

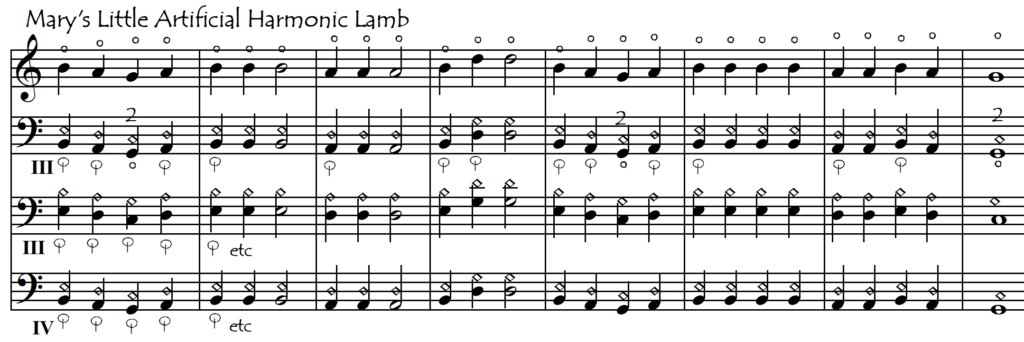

ARTIFICIAL HARMONICS ON THE MAJOR THIRD

Using the harmonic of the major third above the stopped finger is theoretically possible but in practice quite difficult. This harmonic sounds two octaves above the harmonic (higher) finger but it is quite difficult to make it sound (speak), certainly with any reliability. It can be used occasionally as a way to avoid large leaps in slower passages, for example in this excerpt from the opening to Shostakovitch’s Trio Nº 2. The upper line shows the way the passage is written, with standard harmonic fingering. The lower line shows an alternative fingering using harmonics on the third to avoid leaping around.

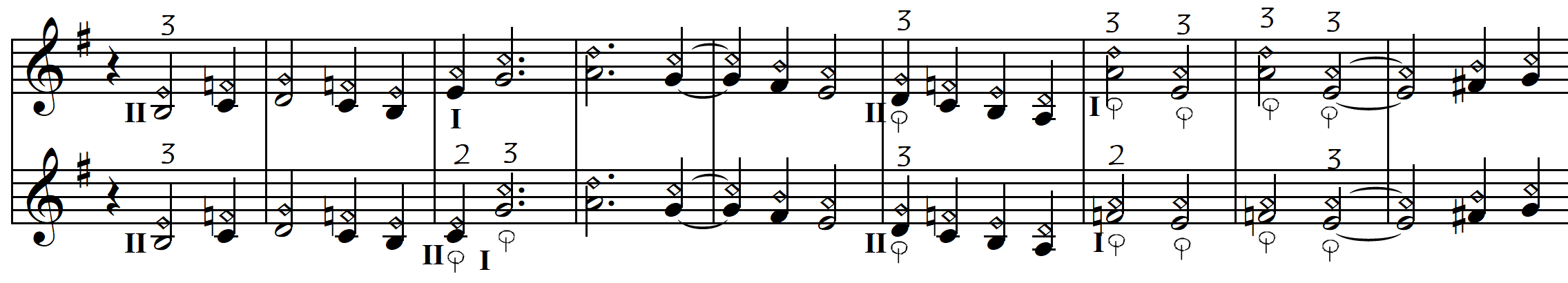

We can experiment with the many different possible ways to play most passages in harmonics, trying different natural and variously-fingered artificial harmonics. Here is a popular children’s nursery rhyme with three different possible artificial harmonic fingerings – we could also play it with two different natural harmonic fingerings in the neck region:

IMAGINATIVE PRACTICE METHODS FOR ARTIFICIAL HARMONICS

In order to practice getting the distances right between thumb and finger, it will be very useful to practice our artificial harmonics as double stops. For normal harmonics on the fourth, placing the top finger on the higher string (instead of on the same string as the stopped lower finger) gives us an octave interval. So, in fact, all practice of octaves and all practice of “artificial harmonics on the fourth” are perfectly interchangeable and mutually useful (see Octaves). To practice the distance of a fifth above the thumb, we can practice the double stop with the third finger on the lower string and the thumb stopping the higher string. This gives us a unison double stop and no other interval is as sensitive to slight inaccuracies of intonation so we will have absolutely no trouble hearing if our distance between the two fingers is correct or not.

WHY MIGHT OUR ARTIFICIAL HARMONIC SQUEAK, SCRATCH OR NOT SOUND?

If our artificial harmonic doesn’t sound (and all we get is a squeak or whistle), this normally tells us that something in the placement of our two fingers is not right. Either the distance between them is wrong, or, for louder playing, the stopping finger is not holding down the string hard enough. We almost always use the thumb as the “stopping” finger, because for a viable, reliable harmonic, the minimum distance necessary between the stopped note and the harmonic is a perfect fourth which, for most hands, is uncomfortable to stretch without the use of the thumb. In order to get a really sure, firm stop of the string with the thumb on the A string we might want to have the thumb only on the A string (and not on both A and D strings) as this allows it to stop the string with the hard edge of the nail rather than with the (often) softer callous.

But this firm stopping of the lower finger (usually with the thumb) is only absolutely necessary if we want to play the harmonic loudly. For soft playing, artificial harmonics can also sound perfectly clearly and cleanly with only a very light pressure of the thumb (or lower finger) on the string, as though that lower finger were also playing a harmonic. We can experiment with just how much thumb pressure is needed to ensure that the harmonic sounds cleanly. This possibility to relax the thumb pressure can make many (soft) artificial harmonic passages (especially those with a lot of shifting) suddenly very much easier.

Another possible reason for an artificial harmonic that squeaks or doesn’t speak can come from our bow. Artificial harmonics do not like to be played sul tasto (with the bow over the fingerboard). In order for them to sound cleanly and resonate strongly, it helps to keep the bow somewhat closer to the bridge than for “normal” notes.

ALTERNATIVES TO ARTIFICIAL HARMONICS

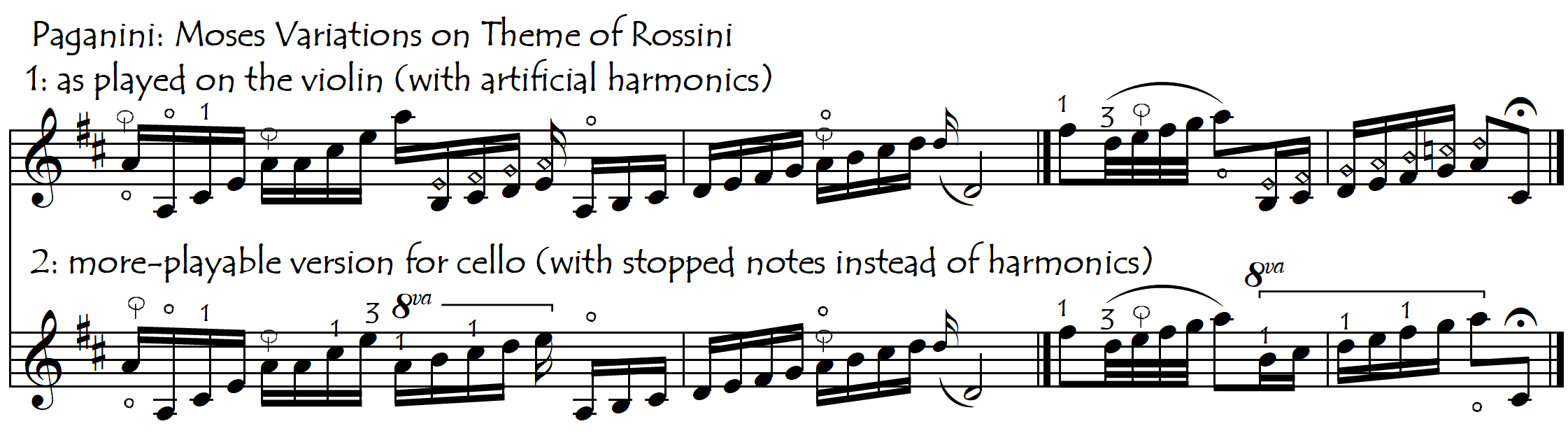

Artificial harmonics sound more easily, and are played more easily (with the simple 1-4 perfect fourth finger distance) on the violin than on the cello. Sometimes therefore, in music transcribed from the violin, the passages in harmonics are too difficult for the cello – usually because they are too fast. We have several alternatives that we can use to avoid the most difficult passages in artificial harmonics:

1: USING STOPPED NOTES INSTEAD OF ARTIFICIAL HARMONICS

The violinist’s left-hand can’t go as high up the fingerboard as the cellist’s left-hand, because their thumb (unlike ours) has to stay behind, stuck in the crook of the neck (violinists don’t use “thumb position”). This means that, in passages for which violinists are obliged to use artificial harmonics (because their hand can’t go any further up the fingerboard) we cellists can in fact sometimes “comfortably” continue up the fingerboard, playing stopped notes. Often this may be technically easier, and sound better, than leaping two octaves backwards down the fingerboard in order to find the artificial harmonics, which is what violinists are obliged to do.

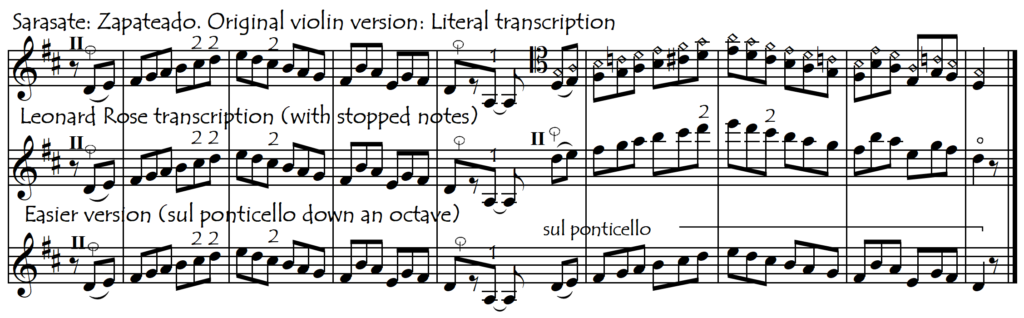

2: USING SUL PONTICELLO DOWN AN OCTAVE INSTEAD OF ARTIFICIAL HARMONICS OR STRATOSPHERIC STOPPED NOTES

The following example is taken from Sarasate’s Zapateado. In the original violin version, artificial harmonics are used in this passage. In Leonard Rose’s transcription, however, the notes are stopped (and very high). We can reduce our difficulty level even further, without sacrificing much of this special effect, by simply playing the notes an octave lower but “sul ponticello”:

Another good example of our use of sul ponticello stopped notes instead of artificial harmonics comes from Bartok’s Romanian Dances, where, just like in Zapateado, our cello artificial harmonics just can’t keep up with the speed and virtuosity of the violin.