Bow Speed

It is difficult to speak about Bow Speed in an isolated form. Before reading this page we need to read the preliminary page “Bow Pressure, Speed, Point of Contact and Hair Angle” which discusses the intimate interrelationships between these four bowing factors. It is also useful to read the specific pages dedicated to each one of these elements, especially the page dedicated to Bow Pressure, with which this page shares certain material.

According to the painting analogy that we used in the Bow Pressure, Speed etc article, bow speed corresponds to the same two elements (darkness and paint quantity) as bow pressure, but in exactly the opposite way. Whereas greater bow pressure leaves more paint on the canvas (or ice-cream in the spoon), a greater bow speed (normally associated with less bow pressure) leaves less paint on the canvas and thus creates a “lighter” and “whiter” sound. A high speed+low pressure bow stroke corresponds to delicate water-colours or pencil drawings whereas a high pressure+low speed bow gives exactly the opposite effect, comparable to thick oil painting. It’s not surprising that the “ultimate” fast-bow (flautando sul tasto) is used so often in French impressionist music, as this type of bowing gives a sound that corresponds perfectly to the lightness and delicacy of the French impressionist painting style.

THE PRESSURE/SPEED RATIO: THE RIP, THE SCRATCH, THE CONCRETE MIXER, AND THE WHISPER

We can see that bow speed and bow pressure are normally like opposites: yin and yang, male and female, black and white, but that they are intimately linked to each other. We could usefully use the concept of the P/S ratio, where “P” = bow pressure and “S” = bow speed. As this value gets higher, our sound gets thicker and denser (oil paints), whereas as it gets lower, our sound gets more and more “airy” (watercolours). And when this value becomes extreme in either direction (high or low), we enter into the world of special effects.

Whereas “sul tasto/flautando” (created by a very low pressure and high bowspeed) is a valid musical effect (like a whisper, a singer’s hum or an airy flute sound), the same cannot be said (except for in experimental music) when the pressure side of the equation goes through the roof. Excess pressure causes some very unmusical sound-effects. When it happens at the start of the note, we get a scratch or a rip, just like when we press too hard on a piece of paper when writing (or on any material). And if we continue with this excess pressure (in relation to speed), then we get the concrete-mixer sound (rough and grinding). Thus the scratch, the rip, and the concrete-mixer sound are the highly audible symptoms of a bow-pressure that is too high in relation to the bow speed. Or, to say the same thing from the opposite perspective, the scratch and the grind are symptoms of a bow-speed that is too slow relative to the bow-pressure.

To fix this, either we speed up the bow, or relax the pressure ……. or both! As a general rule, we could say that an excess of bow-pressure is not only more dangerous but also much more common than an excess of bow-speed. This is why many excellent cellists are very cautious with their use of the word “pressure”, preferring usually to talk more about bowspeed as the source of phrasing and dynamics.

PHRASING AND DYNAMICS: PRESSURE OR SPEED?

Dynamics and phrasing are almost entirely a question of this bowspeed/pressure relationship but energy, vitality and “air” always come from bowspeed. And in fact, dynamics very often refer more to an energy level rather than a decibel level, which emphasises the importance even more of bowspeed in relation to pressure for making phrasing and dynamics. When high bowspeed and pressure combine together, we get the potent fireworks an extremely high energy ff, whereas we can make the difference between a high-energy (french) pp and a tragic deathly pp simply by varying our bowspeed while maintaining an identical pp bow-pressure:

- nervous, high-energy pp = fast bow + low pressure

- tragic, low-energy pp = slow bow + low pressure

There is often a difference between the way we do crescendos and diminuendos on upbows and downbows, according to our relative use of pressure and speed. The natural increase in arm weight that occurs on an upbow as we get closer to the frog gives us a natural crescendo, whereas the downbow has a natural diminuendo because of the diminishing effect of the arm’s weight as we go towards the tip. This means that we can do our upbow crescendos and downbow diminuendos without much variation in bowspeed.

But when our crescendos come on downbows, we will probably want to (or need to) use a large increase in bowspeed to make the crescendo, in order to compensate for the fact that the weight of the arm on the bow (and therefore also the bow pressure on the string) diminishes naturally as we go out towards the tip.

This is especially true when we need to “blast off” with a vigorous bounce on our upbow following the crescendo.

Here below is a link to some exercises that look at these differences between upbow and downbow crescendos:

Upbow and Downbow Crescendos: EXERCISES

BOWSPEED IN SOFT PLAYING: HOW SLOW IS TOO SLOW?

Bowspeed gives vitality, energy, projection, resonance and quality. Even when playing very softly, we still usually need all these ingredients, even in discreet “pp” accompaniments. Think about unamplified theatre and singing. Actors and singers often need to do their stuff (talk/sing) softly, but at the same time, they always need both projection and intensity. A performer’s sound not only has to be heard everywhere in the room, but also must have “resonance” – unless we deliberately want the passage to sound choked, suffocating, dead or dying. It is bowspeed (rather than pressure) that gives us this resonance.

If an actor or singer runs out of breath, their voice not only sounds soft but also weak. They would probably describe this problem as “having no support”. Their support comes from the air that they have in their lungs(?) but in our case, our “support” comes, not from anything to do with pressure, but rather from the speed of the bow. Below a certain bowspeed the string cannot vibrate freely and the sound becomes strangled, as if we were choking or suffocating, exactly like a singer running out of air. For a singer, the solution is to take another breath, but for us, the solution to a choked sound is to use more bow (= faster bow). It is almost always better to discreetly break a slur than to choke for lack of oxygen (bowspeed). We can find thousands of examples of this in the repertoire because composers’ long slurs are almost always just phrasing indications rather than bowing indications – see Choosing Bowings. Also, instead of long whole bows, when playing “pp” it may be better to use more bows in order to stay in the upper half of the bow, where it is so much easier to play softly.

There is however one special effect that very slow bows do provide, apart from the dead sound. A very slow pp bow has a dramatic visual, choreographic effect: suddenly, the movement stops, we are hanging by a thread, holding our breath, our air is running out, we are pleading, whispering, exhausted, afraid, pulled back, hiding, about to burst into tears etc ….. it is hard to make these special effects if we are merrily sawing back and forth with our bow!

2: BOW DIVISION, BOW SPEED, AND CHOICE OF BOW DIRECTION

Normally we plan our bowings to avoid sudden and extreme changes in bow speed, pressure and point of contact (unless deliberately desired for special effects). This planning is called the science of Bow Division and represents the culmination of all our knowledge, mastery and experience of bow use – and also a little bit of simple mathematics. Bow Division is a little like the way in which a singer plans their use of the breath, only considerably more complex because not only do we change our bow so much more often than a singer breathes but also because we play on both inward and outward breaths (downbows and upbows). This means that we sometimes need to do some addition and subtraction, in order to calculate how many rhythmical units we are playing on a downbow and how many we are doing on an upbow in any particular passage.

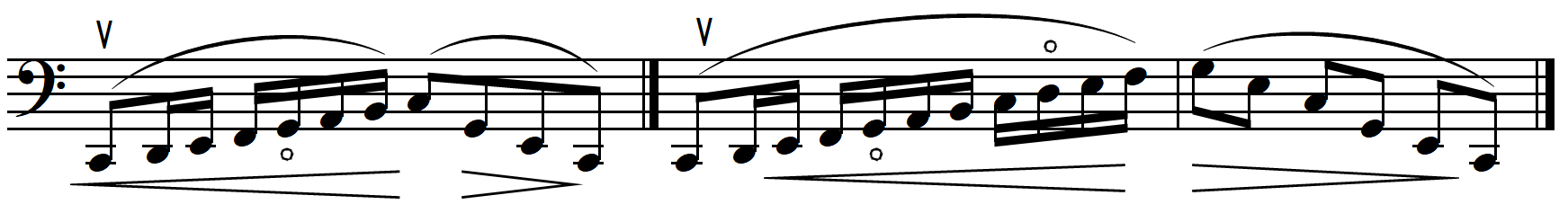

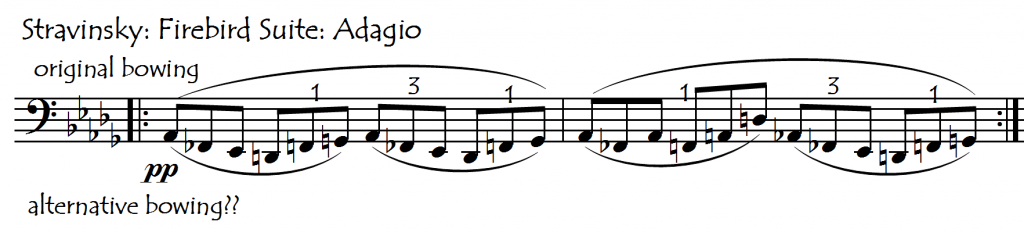

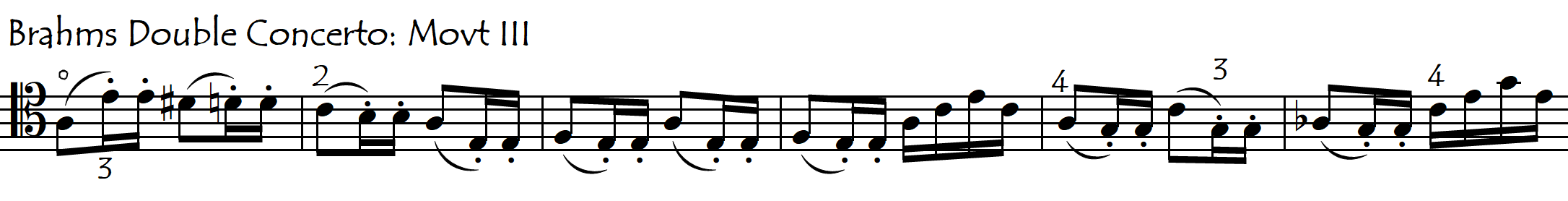

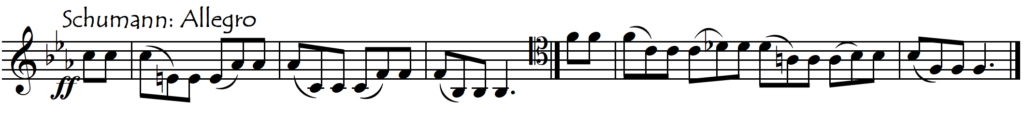

Sometimes, we don’t need to plan anything because this equilibrium between upbows and downbows is balanced, meaning that with a simple alternation of downbows and upbows the music “plays itself” and our bow stays where we want it to be without us needing to do special tricks with either the bow directions or the bowspeed. In the following example, each bar brings the bow back to where it started because in each bar our bow travels for exactly the same amount of time in each bow direction. If we consider the downbows as “+” and the upbows as “-” then the maths gives us +3-1+1-3=0 (there are exactly four eighth notes in each direction):

However, this planning becomes especially complex and difficult in figures in which the alternation of long and short notes note creates “unbalanced” patterns of upbows and downbows (see Dotted Rhythms and Choosing Bowings) as we will see in the following section.

AVOIDING BOW SPEED BUMPS IN UNBALANCED FIGURES: DOTTED RHYTHMS

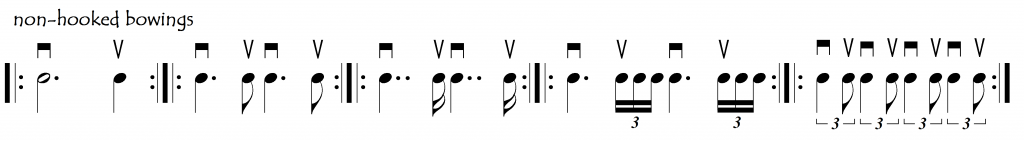

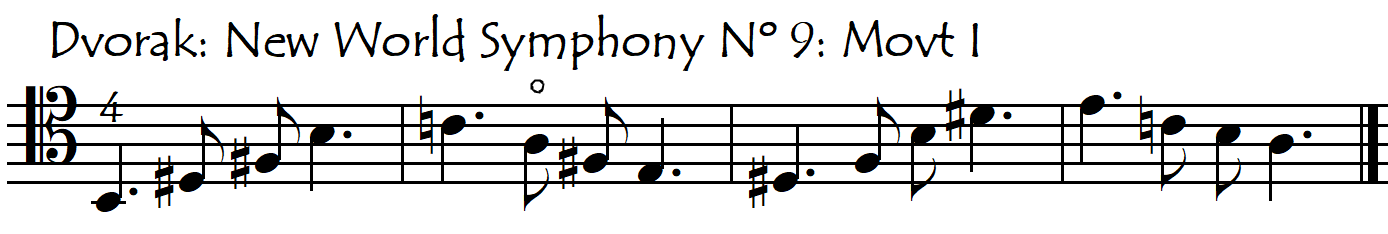

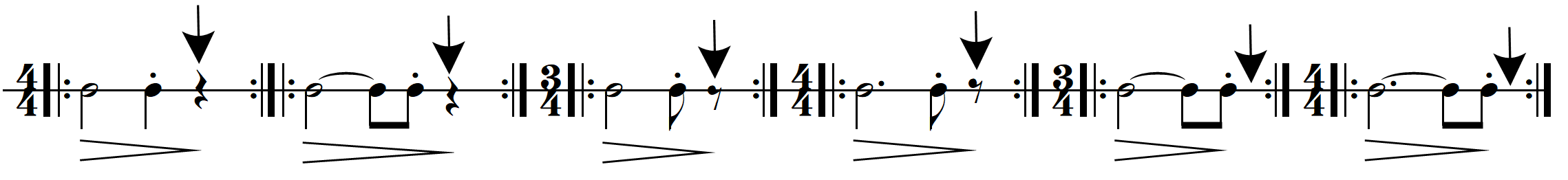

“Unbalanced” bow patterns – especially repeated dotted rhythm figures – pose special problems for Bow Speed and Bow Division. Try the following patterns:

These repeated dotted rhythm figures create the danger of “speed bumps” or “bunnyhops” (accents on the short bow strokes) produced by the fact that, if we play these figures with a simple alternation of down and upbows (“as-it-comes”,) we have to use a much faster bow on the short strokes in order to avoid our bow gradually working its way more and more to the tip. There are several ways in which we can change the “as-it-comes” bowings in order to avoid the need for radical changes in bow speed and pressure and thus avoid the risk of “speedbumps”. Let’s look at these bowing “tricks” now:

3:1 “RETAKING” THE BOW

If we can lift our bow off the string before or after the short note, then this enables us to move our bow, silently in the air, back to where we want it to be. This, along with “hooked bowings” (see below) is one of the easiest ways to solve the problems of bow division posed by repeated dotted figures. We have two choices for when to retake the bow:

1: In a brief “gap” after the long note:

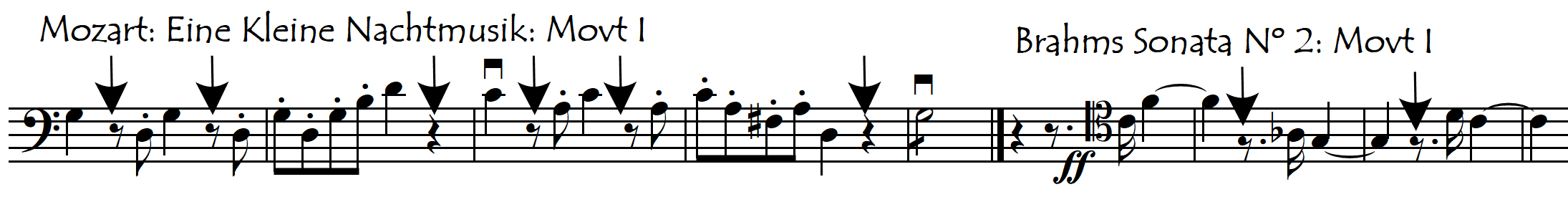

It is surprising just how often we can make this “gap” after the long note, even when it is not specifically written as a rest. If, near the end of the long note, we remove the bow from the string in the appropriate way (see Note Ends), that long note will keep sounding even without any bow contact, and this resonance – like the piano’s sustain pedal – creates the aural illusion that we are still sounding it with the bow. Basically, what we are doing then is putting in a little comma, during which we bring the bow back towards the frog. Below, the retakes are indicated with arrows.

In all of the above examples we are retaking from a downbow to an upbow. We can of course also go “the whole way”, and retake to another downbow, as in the following example:

2: We can also retake sometimes after the short bow and before the next long bow (rather than in the above examples where we always retake after the long bow and before the short bow). In the following exercises we have progressively less time to do our retake:

We have a whole article dedicated to “The Retake” (click on the link)

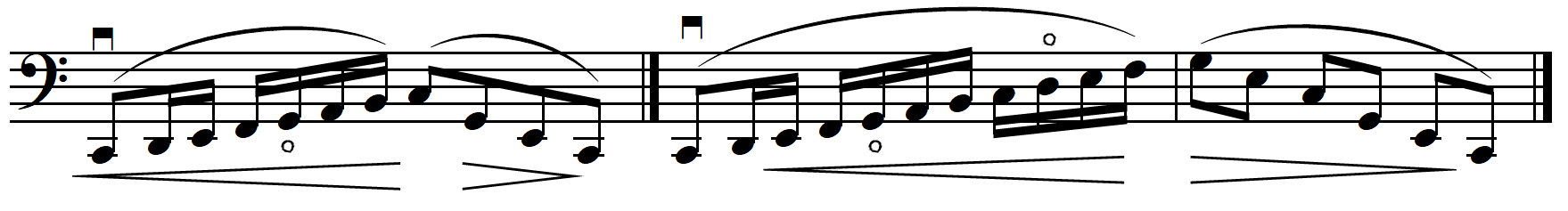

3:2 HOOKED BOWINGS

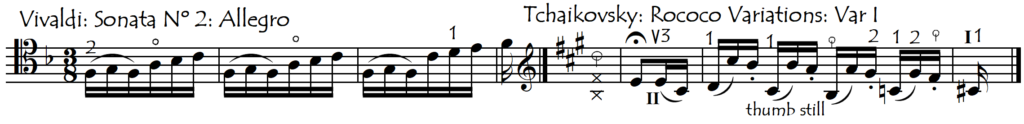

Very often we will encounter asymmetrical figures in which we don’t have enough time to do a retake. In these situations we will most probably use “hooked” bowings, in which we “hook in” the little note in the same bow direction as the previous longer note to avoid “speed bumps”.

The back legs of rabbits are much more powerful than their front legs. This is why their running rhythm resembles more a dotted rhythm than the regular binary flow of other animals whose front and back legs are more symmetrical. Playing asymmetrical rhythms with hooked bowings avoids our sudden fast bow stroke giving this same “bunnyhop accent” to the short notes.

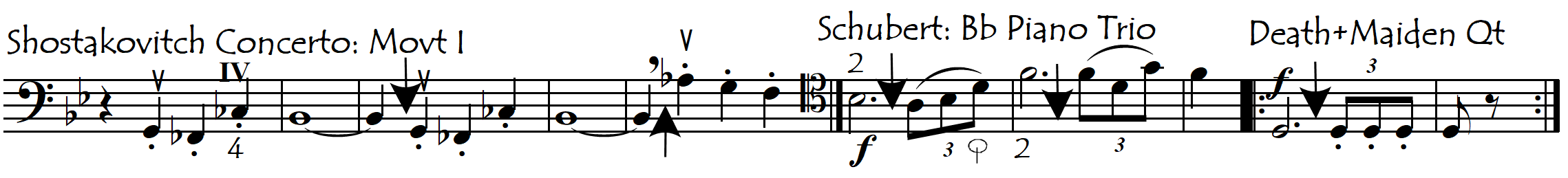

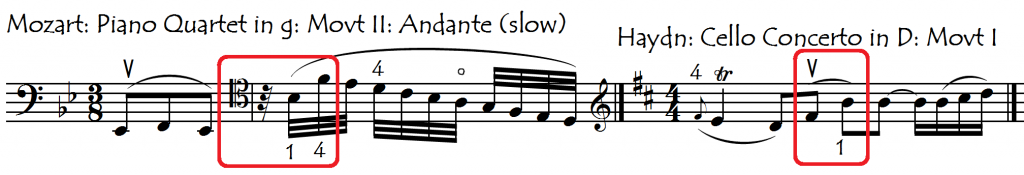

Retakes and hooked bowings are a wonderful solution for avoiding bunnyhop accents. Both of these subjects have their own dedicated pages (click on the highlighted links). Unfortunately however, their use is not always possible and sometimes we have no choice but to use radical changes of bowspeed in order to stay in the same part of the bow. Sometimes this is a desired effect by the composer:

For a more detailed discussion of these situations, and about finding the right bowing for asymmetrical musical figures in general, see the “Choosing Bowings” section.

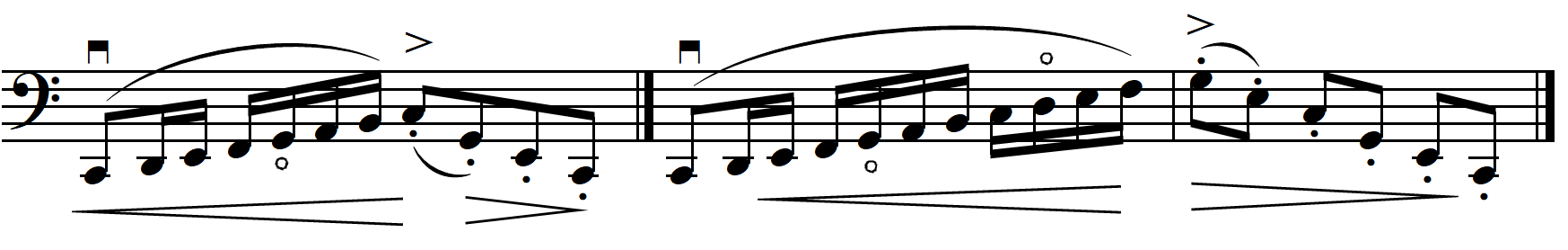

UNAVOIDABLE RADICALLY ALTERNATING SPEED/PRESSURE CHANGES

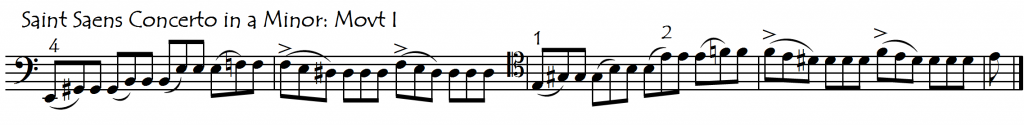

Sometimes however, we cannot use hooks and retakes to avoid the need for radical bowspeed changes and we have to do miracles in order to stay in the same part of the bow. The word “radical” is very appropriate here as the changes in the bowspeed/bowpressure relation that we need to make (in order to avoid either making accents on the short strokes or ending up in the wrong part of the bow) are both huge and sudden. For the longer bowstrokes, we need heavy bow pressure and slow bow speed, whereas for the short strokes, we need just the opposite: fast speed and low pressure. This rapid alternation of opposites is quite tricky to achieve and almostfalls into the category of a magic trick. The key to making these types of passages easier is to release the bow pressure quickly at the end of the longer stroke, basically shortening it, which helps to reduce the asymmetry of the figure.

Often, composers don’t realise the problems that these articulations pose for bowed-string instruments because for players of keyboard, wind, and plucked string instruments (as well as singers), these types of articulation present no special difficulty at all. In the Romantic Period however, these types of unbalanced bowings are often used deliberately, to achieve a very agitated effect. In these cases, even though it might be a good technical idea, shortening the longer bowstroke may not be a good musical idea because it can make the music sound too “Baroque” or “Classical”.

The following link opens up several pages of repertoire excerpts of this type, in which we cannot choose an alternative bowing and are thus obliged to develop our bowing virtuosity:

Unavoidably Unbalanced Bowspeeds: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

BOW SPEED VARIATION IN SHIFTS

Very often, to hide an unwanted glissando in a slurred position change we can simply slow down the bow speed (and/or reduce the pressure) during the shift, making a sort of portato effect. If we do this discreetly, then the interruption to the legato line can be imperceptible, whereas the musical advantage of avoiding an unwanted smear/smudge can be considerable. This is especially useful in music of the Classical Period in which glissandi were not yet the important expressive device that they became in the Romantic Era.

This technique is also useful to help with obtaining a clean start to any note that is slurred to an immediately preceding harmonic on the same string. If we maintain constant bow speed and pressure after the harmonic, then the new finger has a high risk of starting with a squeak rather than with a clean start. The exceptional resonance of the simple natural harmonics means that the interruption to the legato line due to this momentary bow relaxation is usually imperceptible.

BASIC EXERCISES FOR VARYING BOW SPEED

Just as for “Point of Contact” and “Bow Pressure”, we can observe the interrelationship between Bow Speed and the other bow variables by experimenting along the following lines:

1. Vary the bow speed without changing any of the other variables (pressure, point of contact, bowhair angle, left-hand position)

2. Vary the bow speed while simultaneously varying one other variable, for example:

………. left-hand distance from the bridge

……….. bow pressure

……….. point of contact

3. Vary the bow speed while simultaneously varying two other variables, for example:

………. left-hand distance from bridge AND bow pressure

……… left-hand distance from bridge AND point of contact

………. bow pressure AND point of contact