The Retake as A Bowing Technique

This page is a subdivision of the “Bow Trajectory In The Air” page.

What is a “retake” ? Even though it sounds like something from Japanese cuisine (like shiitake mushrooms and the “sake” drink) it is actually a simple and fundamental bow technique. With a retake, instead of starting our new bow impulse from the point at which the bow finds itself after the previous bowstroke, we make use of a little musical space (silence or resonance) to bring it silently, in the air (usually but not always), and in the opposite direction, back to the position that we want it to be in for the next note.

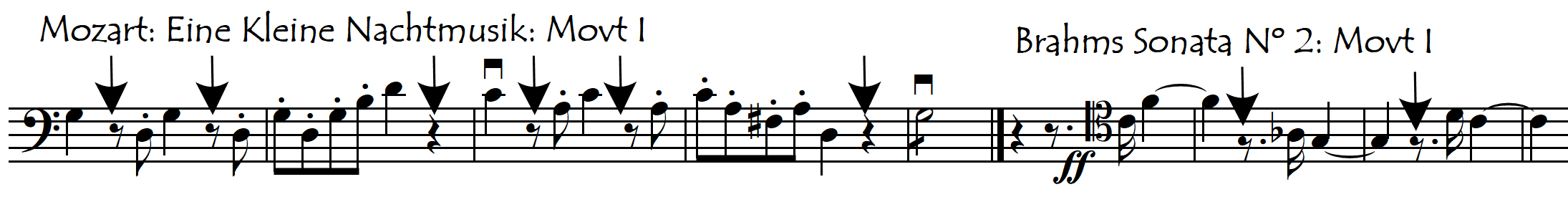

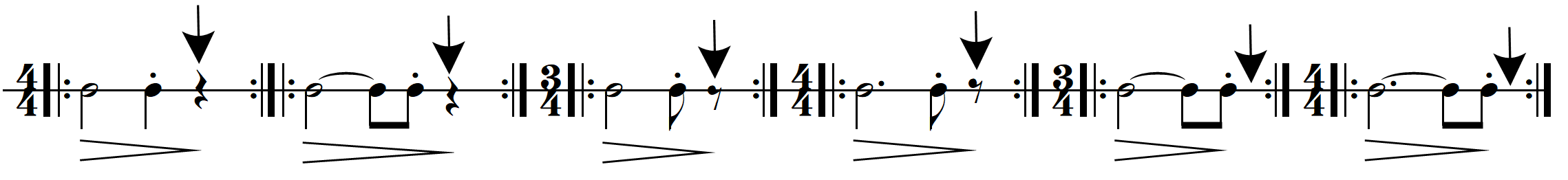

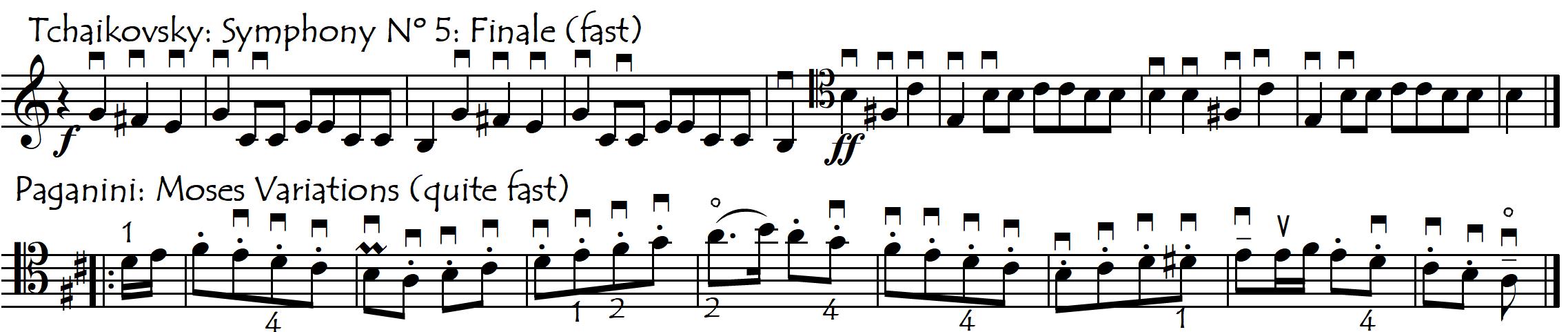

This is best illustrated by some musical examples in which the moment of the retake is indicated by the arrows:

Just like in the above examples, the use of the retake allows us to solve many problems of bow division and bow speed in rhythmically asymmetrical figures.

Unfortunately, no music scores provide any indication for this choreography (bowing) of the retake, not only because no standard sign exists in music notation but also because there are other bowing alternatives to the retake (namely the “hook“) and no editor or composer wants to tell a string-player how to play their instrument. This lack of “instructions” is regrettable for inexperienced players, because the retake is a very frequently needed component of our bowing toolbox.

In the edited sheet music available on this website, rather than overloading the staves with thick invasive arrows, we have tried to find an alternative solution to indicate retakes. But in the end, rather than indicating the retakes, we have preferred to indicate instead the hooked bowings, which are always indicated with dotted slurs. Therefore, in the absence of a dotted slur between two consecutive bow strokes in the same direction, the retake becomes the default solution. In some editions, a comma is used to indicate a retake but this is definitely not the optimum form of notating a retake because in most printed music a comma indicates a rhythmical delay.

The above examples illustrate the most common type of retake, which is the bringing of the bow back towards the frog for a short upbow after a longer downbow. In this, the most common retake, we lift our bow off the string and bring it towards the frog before the short note. In order to be able to do a retake, we need to have a “musical space” between the notes that is long enough to permit us to bring our bow back silently to where we want it to be without disturbing the musical line. In the above examples, the “retaking” of the bow occurs during notated rests, but this is not always the case. Sometimes there is no notated “rest” and the “musical space” between the notes (the space in which we will do the retake) is indicated by a staccato dot on the note previous to the retake. But at other times there may be neither a rest nor a staccato dot to give us the “retake time” between the long and short bows of an asymmetrical figure. In these cases we will need to “steal” the time for the retake from the long note by shortening it slightly, making an almost inaudible “gap” after the long note, even when it is not specifically notated as a rest or dot:

It is surprising, not just how easy it is to do this “theft” but also how frequently we need to do it. The secret to this “magic trick” is “resonance“. If, near the end of the long note, we release the bow from the string while still maintaining plenty of bowspeed (see Note-Endings), that long note will keep sounding even without any bow contact, and this resonance – like the piano’s sustain pedal – creates the aural illusion that we are still sounding it with the bow. It is during this resonance that we bring the bow back towards the frog. No matter how it is notated – with a notated rest or not – the musical space (time) in which we do our retake is full of the resonance of the previous bowstroke. So when we talk about making the note previous to the retake a little shorter, we only mean reducing the time that the bow is pressing on the string. The resonance continues for the note’s full value.

The fact that in pre-romantic music we tend to sustain the long notes less than in romantic music, means that the retake is used especially frequently in these earlier musical styles. In romantic music, the need to hold/sustain the longer notes till the end means that, in asymmetric figures, we will probably use hooked bowings rather than retakes as our preferred bowing solution.

RETAKING TO WHICH NEW BOW DIRECTION ?

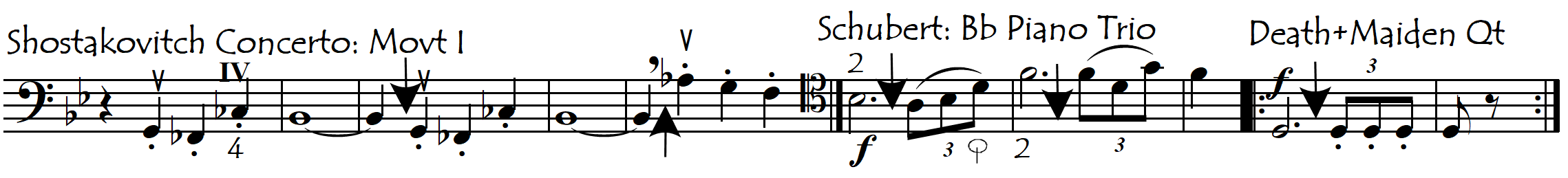

In the previous examples, all the retakes were from downbows to upbows but, in fact, our retake can be followed by a new bowstroke in either direction. Sometimes we will retake from a downbow to another downbow:

Less often, we will do retakes from upbow to upbow, or from upbow to downbow. In all the above examples, our retake brings the bow back towards the frog/lower half. In the following examples, however, our retake brings the bow out towards the tip/upper half:

So, in fact, we can retake from any bow direction to any bow direction, and from any part of the bow to any other part of the bow.

RETAKING AFTER THE SHORT NOTE

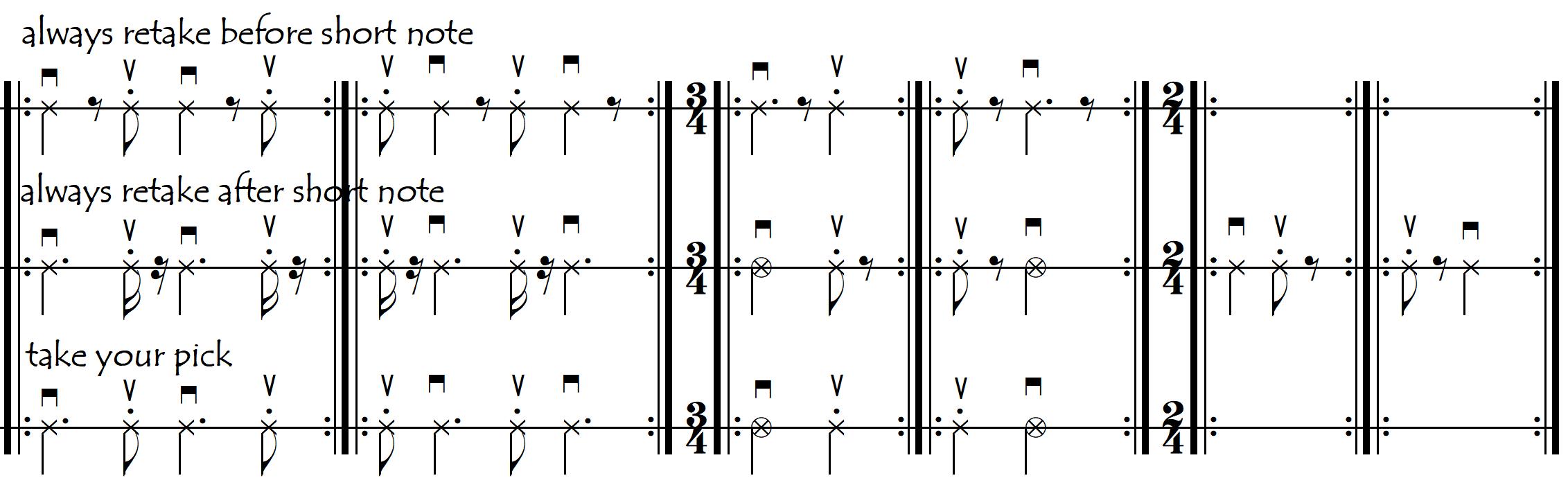

Most often we will do our retake after the long note (before the short note). This is the case in all the above examples. But sometimes we will, by choice or obligation, need to do the opposite, bringing the bow back towards the frog in a brief gap after the short note. In the following figures, we have progressively less and less time in which to do our retake.

And here is a musical example of the extreme case of this retake after the short note, done here with very little time. We will make use of the bounce to get us into the air and flying back as quickly as possible.

Sometimes (as in the above example) our choice between the two options (retake after long note or retake after short note) is absolutely clear, but at other times our decision could go either way:

In the above discussion, we have always talked about the retake between long and short notes, but in fact, a more accurate way to describe the retake would be to use the terminology of long and short bowstrokes because we can have many or several notes in our bowstrokes on either side of the retake.

TO RETAKE OR NOT TO RETAKE ? HOW FAR TO RETAKE ? IN THE AIR OR LIGHTLY ON THE STRING ?

A retake is, like so many other things in life, not an either/or phenomenon. We can do a big retake all the way to the end of the bow or a small retake to gain just a few centimetres. We can retake high in the air or we can keep the bow touching (barely) the string. Or we can choose not to do a retake at all, preferring to use a hooked bowing or a radical bowspeed change.

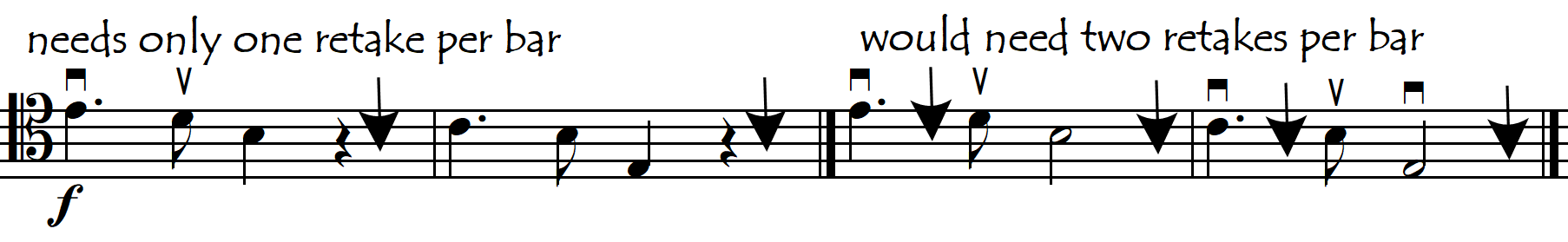

Look at the following figure from the orchestral opening of Brahms’ Double Concerto. We don’t need to retake after the first long note, but we definitely do after the second one. If, however, Brahms had written his rhythm slightly differently, we might have needed two retakes in each bar:

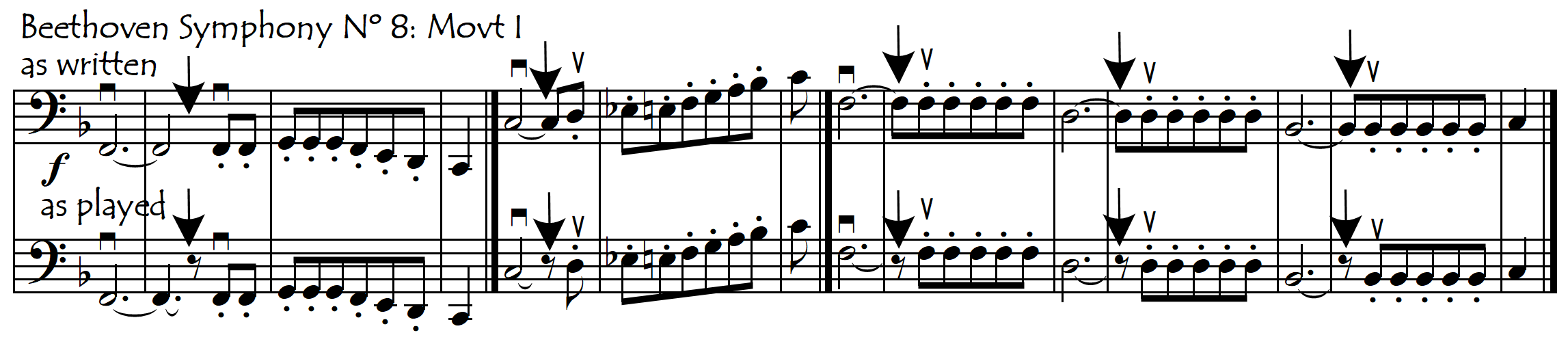

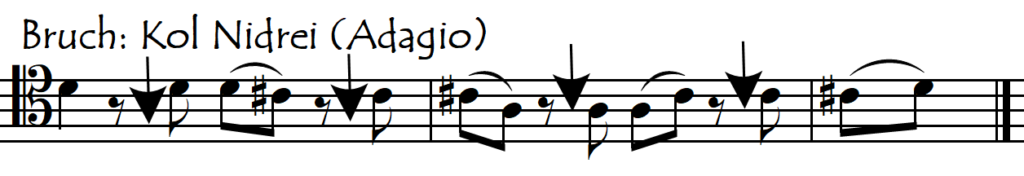

If we retake to the lower half of the bow we are very likely to bring the bow in the air, but if we do a smaller retake to the middle or upper half of the bow then we might want to keep the bow in VERY light contact with the string during the retake in order to avoid a hard bouncy landing. In the following example, most players retake, some don’t at all, while others retake just a little. As this thematic motif comes back several times in the piece in different registers and with different dynamics, we can experiment with the different retake options and use this theme as a “retake laboratory”. One thing is absolutely certain though: rather than being a silence, the rests are absolutely full of resonance (see Reading and Notation Problems).

Certainly, when we retake to an upbow at the tip/upper half it will normally be easier to keep the bow very lightly (and inaudibly) in contact with the string rather than lifting it up in the air:

WHY RETAKE?

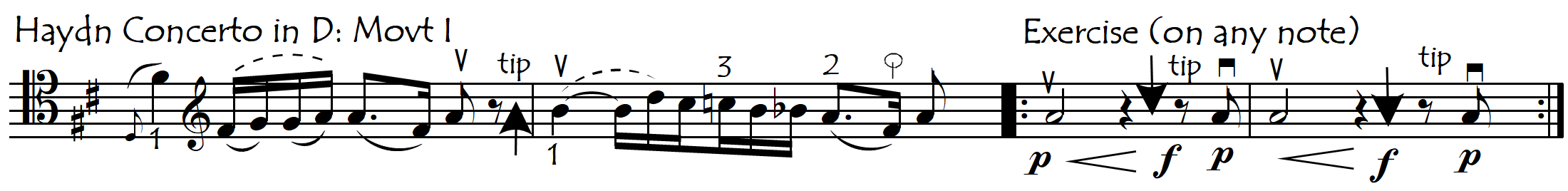

There are many reasons for which we might decide to retake our bow. In order to play as expressively and as easily as possible, we need to plan our bowing directions (bow choreography) so that our bow is taken effortlessly to where we want it to be. Basically, a retake is simply a means to get to the part of the bow that we want to be in for the next note. Some of the reasons for a retake might be purely technical, others are purely musical, but most often the reasons for a retake are a combination of the two. Many musical effects are much easier (more natural) in a specific part of the bow or in a specific bow direction (diminuendo towards the tip, crescendo towards the frog, pianissimo at the tip, spiccato in the lower half of the bow, sforzando at the frog etc). Crunchy attacks are much better at the frog, which is why some passages use a succession of “retaken” downbows to give that extra energy, each note being like the crack of a whip – with the wrist having a wild workout:

Most commonly, we will use retakes for simple reasons of bowdivision: for example to avoid extreme bowspeed changes (and their resulting unwanted accents) in rhythmically asymmetrical passages (as is the case in most of the musical examples given above). At other times, however, our use of the retake is exclusively for visual, choreographic reasons

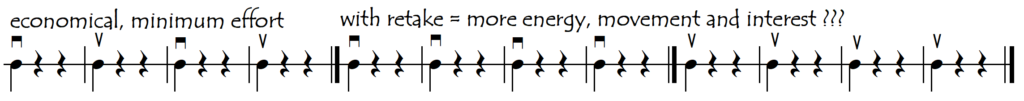

As-it-comes bowings (in which we simply alternate up and down bows as though we were using a saw to cut wood) are usually the most simple and economical bowings in terms of energy expenditure and intellectual effort but are also the most neutral/inexpressive in terms of body language. Even though the use of retakes may not be necessary from a technical point of view (bow division, bow bounce etc), their use can add a huge amount of interest, character, energy and attractiveness to the same notes because now our bow and right arm are obliged to move a lot more. This idea can be valid in music of any speed and dynamic. Now we are dancing instead of mechanically sawing back and forth:

PRACTICE MATERIAL

Click on the following link to open up a compilation of repertoire excerpts in which can be found examples of all the different varieties and permutations of “the retake”: