Technical Fingerings On The Cello

This is a sub-article of the page dedicated to fingerings. Here we will look at different ways in which we can use fingerings to make difficult technical passages physically easier to play.

1. FINGERINGS TO REDUCE THE USE OF EXTENSIONS:

This is such a large and important subject that is has its own dedicated page

Fingerings To Reduce The Use Of Extensions

This extensive article concerning how to reduce the use of extensions can be summarised into the following two main fingering tactics:

- use the thumb more (especially in the Thumb Region and Intermediate Region)

- shift more often

2. FINGERINGS TO AVOID (OR TO SEPARATE) SHIFTS:

If the shifting in a passage is causing us technical problems (insecure intonation etc), we have two possibilities to eliminate this difficulty: either we work on our shifting and our positional security, or we change our fingering to either avoid the shifts or to at least space them out in time. There are several ways to use fingerings in order to avoid shifting problems:

- START (AND STAY) UP HIGH: FINGERING ACROSS THE STRINGS

This situation occurs frequently in the higher regions of the fingerboard. Whereas a very skilled cellist may be comfortable fingering very difficult passages using shifts up and down one string, others of us may prefer to opt for security and stay “in position”. This usually means starting up high on a lower string, so that we can find our high position tranquilly and securely in the silence (or in the music) before the phrase starts. By staying in position up high (fingering across the strings in the same position) we can avoid the dangers of large shifts up into (and in) the stratosphere.

Click on the following link for more repertoire examples of these types of fingering:

Staying (Or Starting) Up High: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

- SPREAD THE LOAD

If we divide the shifts across several different strings we can reduce the number and size of our shifts and give ourselves more time between the shifts. What this normally means is that, instead of doing all our ascent into the high regions uniquely on the A string, we can do some of our climb also on the lower strings.

- USE OF THE THUMB IN THE NECK AND INTERMEDIATE REGION

The use of thumbposition gives us suddenly an extra finger to play with and is often a way to reduce the number of shifts in a passage. With the thumb up on the fingerboard we can now play like violinists, with all the notes of the scale under our hand without any need to shift. See “Advantages of Thumbposition” and “Use Of Thumb In The Neck Region“.

- USE MORE CONTRACTIONS AND SNAKES

Fingerings using contractions and snake movements are another way in which we can eliminate smaller shifts. Click on the highlighted link for more details

3. FINGERINGS TO AVOID SHIFTS TO AN EXTENDED FINGER

An extended finger is more strained and more unstable than an unextended finger. This, especially for cellists with a small hand, can lead to insecure intonation when shifting to an extended finger. Shifts to the extended first finger are a particularly frequent source of intonation insecurity, especially if the finger has to be placed from midair (after an open string or harmonic).

4. FINGERINGS TO GIVE US A MAXIMUM AMOUNT OF TIME

Here, we choose our fingerings according to the rhythm of a passage in such a way as to have the most time possible for the difficult movements (shifts, jumps across strings, extensions etc).

What this means essentially is that it is usually a good idea, especially in faster passages, to do our shifts and string crossings before the short notes (= after the long notes), because that is when we have the most time. Immediately after the short note is when we have the least time, so any movement done after the short note will have to be done quickly (see Fast Playing). For this reason, dotted rhythm passages often benefit considerably from a little more thought as to which fingerings to use. Using “standard” fingerings, and/or shifting only when we need to (at the last minute) can cause us to get tangled up.

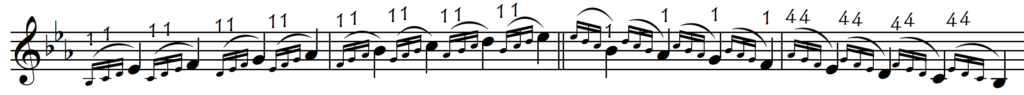

In the following scale passages, even though the sequence of notes is identical in the three examples, we need to do a different fingering for each one if we want to avoid unnecessary “panic” shifting. Of course in sight reading we may not have time to work out the most ergonomic fingering, which is why sight reading difficult music can be quite unrewarding.

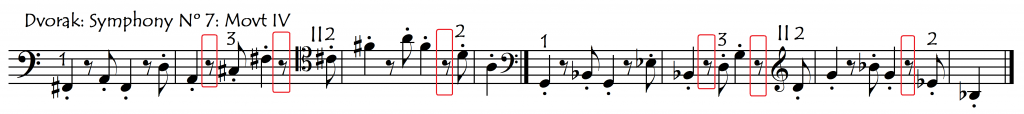

The repertoire is full of examples where we can put this principle to good use. It doesn’t only concern dotted rhythms: we simply want to shift where we have the most time. In the repertoire example below, by shifting after the long notes (in this case, during the rests as indicated by the red enclosures) we are giving ourselves much more time to do the shifts than if we were to shift after the short notes.

5: SHIFTING UP ON THE FIRST FINGER (AND DOWN ON THE TOP FINGER ?)

Because of the angle of the hand and fingers to the fingerboard, it is almost always more ergonomic to shift upwards on the first finger than on the higher fingers. This principle applies in every fingerboard region. Shifting downwards on the top finger is an ergonomic fingering principle that is very useful in the Neck Position but is much less valid in the higher fingerboard regions.

The following link opens up two pages of exercises for working on this skill:

Shifting Up On First Finger (And Down On Top Finger ?): EXERCISES

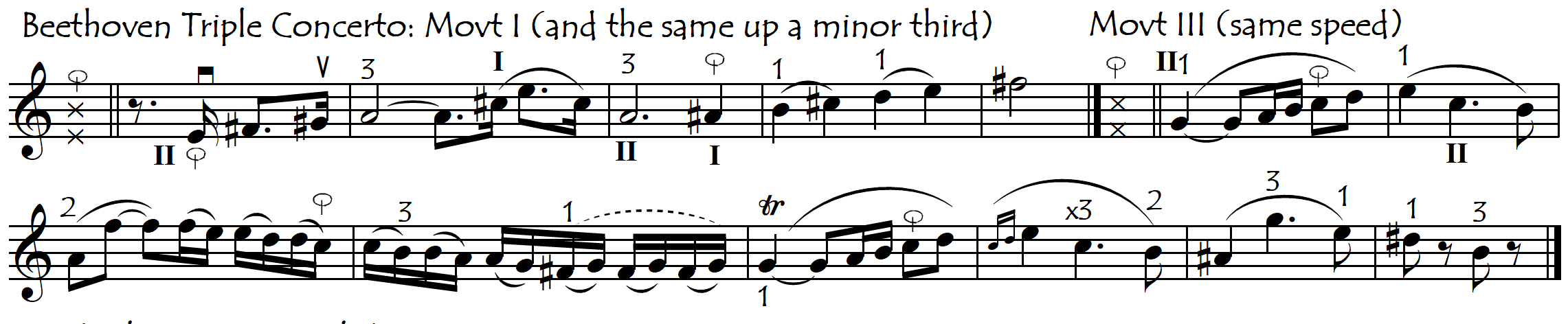

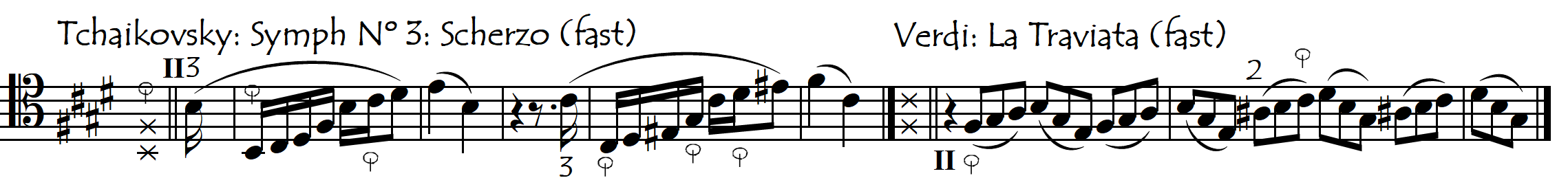

Shifting Upwards On First Finger And Downwards On Top Finger: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

PATTERN FINGERINGS TO AVOID BRAIN OVERLOAD

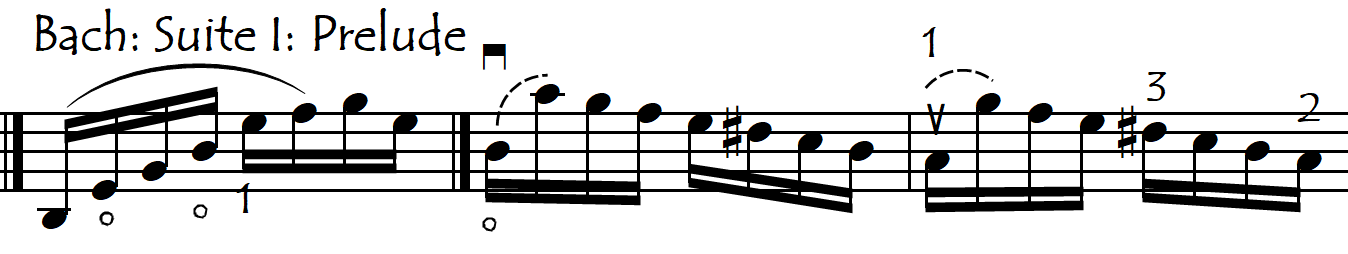

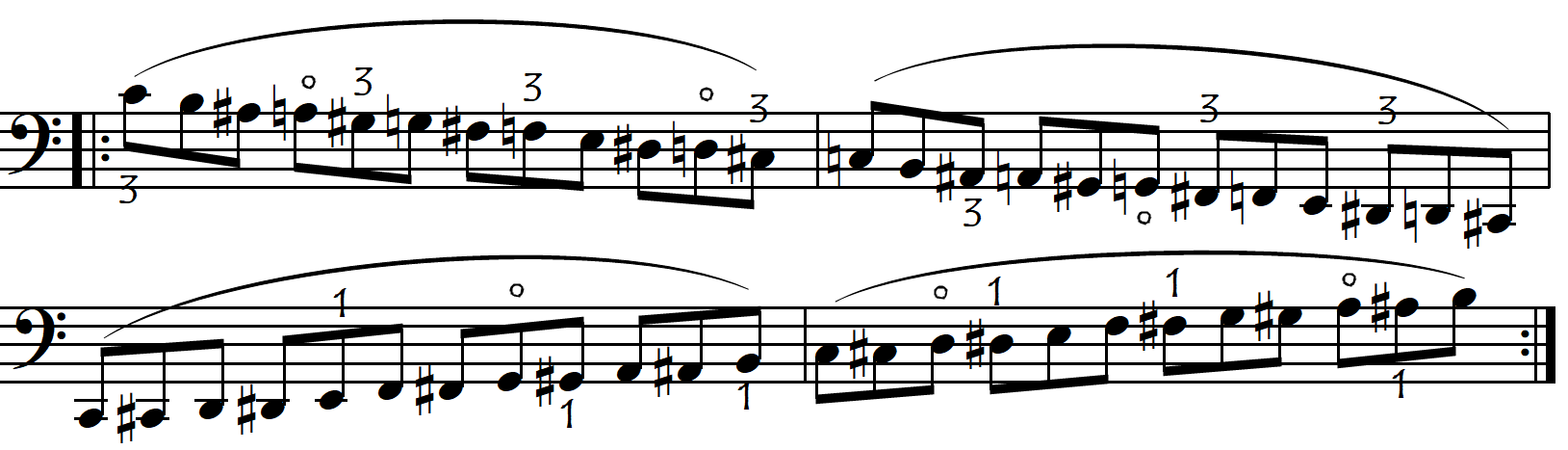

Sometimes we can make our difficult passages easier if we use fingerings that simply repeat themselves over and over (pattern fingerings). Perhaps ergonomically these may not be the ideal fingerings, but the fact that the pattern repeats itself makes the job for our brain so much easier that this compensates for the diminished ergonomy. Chromatic scales across open strings give many good examples of this:

The following link opens up several pages of repertoire excerpts in which we can make use of these types of pattern fingerings: