Left-Hand String Crossings

WHAT ARE “LEFT-HAND STRING CROSSINGS”

While the word “shifting” describes the vertical displacement of the left-hand up and down the fingerboard, the term “left-hand string crossing” refers to the horizontal displacement of the fingers across the fingerboard, between the different strings. The left hand’s “vertical” positional sense (“how far up the string am I?”) is discussed on the highlighted page as well as in the shifting department. On this “Left-Hand Stringcrossings” page however we will look uniquely at the hand’s “horizontal” positional sense (“how far across the fingerboard am I?”, or in other words, “which string is the finger on?”).

STRING CROSSING PROBLEMS: LEFT HAND OR RIGHT HAND?

When we think about (and work on) our technique of “String Crossings” we almost always focus uniquely on our right hand (i.e. our skill at Bow Level Control). It is however also interesting and useful to work on our left-hand’s horizontal positional sense. This factor (skill) is often overlooked as a source of problems in complex multi-string passages.

In some problematic multi-string passages – series of broken chords with many open strings for example – the string crossing difficulties may be almost exclusively bowing problems. In other passages – series of broken chords with few open strings but many changes of the fingers between different strings for example – the left-hand component of the string crossing difficulties may however be considerable. And in other passages (the majority), our string crossing difficulties may be a mixture of complications for both hands (and for the coordination of the two hands).

SEPARATING THE STRING CROSSING PROBLEMS INTO LEFT AND RIGHT HANDS

Fortunately, it is not difficult to separate these two elements of string crossing (right and left hands) in any particular problematic passage. To isolate the bowing aspect we simply remove the left hand completely and play the passage on open strings, whereas to isolate and work exclusively on the Left-Hand problems involved in a string crossing passages we can simply play the passage pizzicato (which may involve chordal strumming rather than rapid individual plucking) or, in the case of a passage involving only two strings, we can practice the passage as double stops (keeping the bow always on both strings at the same time).

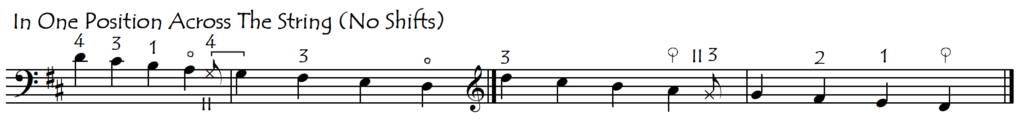

To totally eliminate the string-crossing factors for both right and left hands, we can play a multi-string passage on only one string:

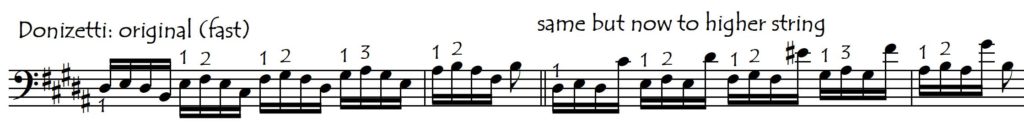

And as a “fun” practice method (to avoid the boredom of repeating the same passage always identically) we could make the string crossing to a different string:

WHY IS THIS ASPECT OF TECHNIQUE NOT USUALLY WORKED ON SPECIFICALLY?

Every string player practices specific material to develop their right hand’s control of bow level (string crossings), and we also spend an enormous amount of practice time on our left hand’s “vertical positional sense” (shifting). So why then do we usually just take the left hand’s “horizontal” positional sense (across the strings) for granted, spending very little time working on this aspect of our technique ?

Shifting movements cover a wide range (distance). The maximum range (distance) from the lowest positions to the highest covers about 60cm (corresponding to a musical range of approximately 3 octaves), although most of our playing occurs in the first (approximately) 55 cm, corresponding to 2.5 octaves. This musical range of 2.5 octaves is composed of 30 semitones (12 + 12 + 6), which means that, within that useful fingerboard distance of 55cm, we need to be able to locate 30 different points. If the cello was like a piano (with the notes located an equal physical distance from each other in every octave), then this would imply one “note” every 18mm (550mm divided by 30). Unfortunately, the semitones are not equidistant from each other but rather get closer together as we go higher up the string. To make matters more complicated, there are very few visual or tactile indicators to help us distinguish these points (notes) from each other: we basically only have our ears and our kinesthetic sense to know when we are in the right place. All this means that these 30 notes on each string are not easy to find. This is why we need to practice our vertical positional sense (shifting skills) so much.

Some of these same problems occur, but to a much lesser degree with our Right Hand String Crossings (bow level control). Here, as with shifting, we only have our ears to tell us which string we are playing on but, fortunately, there are only four separate points to locate (one for each string) within the maximum range of distance between the top and bottom strings. And, to make it even easier, these four points have a considerable margin of error compared to the almost zero tolerance permissible for our left hand’s vertical positional sense (shifting/intonation). This is why we usually practice “shifting” much more than we work on our “string crossing technique”. Curiously, the distance range that the right hand and bow cover between the highest and lowest strings (the arc of 40-50cm that is described by both the tip of the bow while playing at the frog or by the wrist when playing at the frog) is quite similar to the fingerboard shifting distance range covered in “normal” playing by the left-hand.

Left-hand string crossings are quite a different story to both these other elements of positional sense. Left-hand string crossing movements cover a maximum range of only about 5cm (between the lowest and highest strings). Within this distance, there are only four different points (strings) that we need to locate, and to make matters easier, these points are clearly differentiated from each other both visually and for our sense of touch.

So, this is why, in the hierarchy of technical difficulty, shifting is far above bow level control, and left-hand string crossings is right down the bottom, almost taken for granted most of the time. Thanks simply to our many hours of playing and to the fact that we usually only play one note (and thus one finger) at a time, our fingers normally, “know where to go” in order to find the new string. But there are in fact many specific situations – most notably involving chords, double stops and/or fast playing with rapid leaps across the strings – which benefit considerably from giving some attention to this aspect of left-hand technique:

VERTICAL OR HORIZONTAL: HARMONY OR MELODY ?

Keyboard players and guitarists are used to playing several notes at the same time. They thus learn, almost automatically, to think, play and memorise music both harmonically (vertically) and melodically (horizontally. We string players, on the other hand, are principally horizontal, melodic thinkers because we normally only play one note at a time. Because of this, we can be quite weak at both thinking harmonically (memorizing chords, double stops and large intervals) and playing harmonically (placing several fingers simultaneously on different strings).

Playing vertical, “harmonic” music, with lots of chords, double stops and leaps (between bass harmony notes and tenor melody notes or simply melodic leaps ) is a good way not just to develop our harmonic thinking but also to develop our Left Hand String Crossing ability. In fact, this article has considerable overlap with the article on Doublestops, and can in fact be considered as the first stage in working up to double-stops and chords.

Vertical, harmonic writing is however not only manifested by the use of actual chords and double stops (in which the bow is playing on two strings at the same time) but also by the use of “broken” chords and double stops. Here, the bow plays only one note at a time, but the intervals are chordal (arpeggiated) rather than purely melodic. We can play these arpeggio intervals across the strings or with shifts on the same string, but the closest fingering of an arpeggio interval (especially a larger one) is usually just across on the neighbouring string (changing strings is like taking a shortcut to a distant note). When we play these arpeggio intervals across the strings – especially if the music is fast – the left hand is often obliged to play as though it were playing actual double-stops.

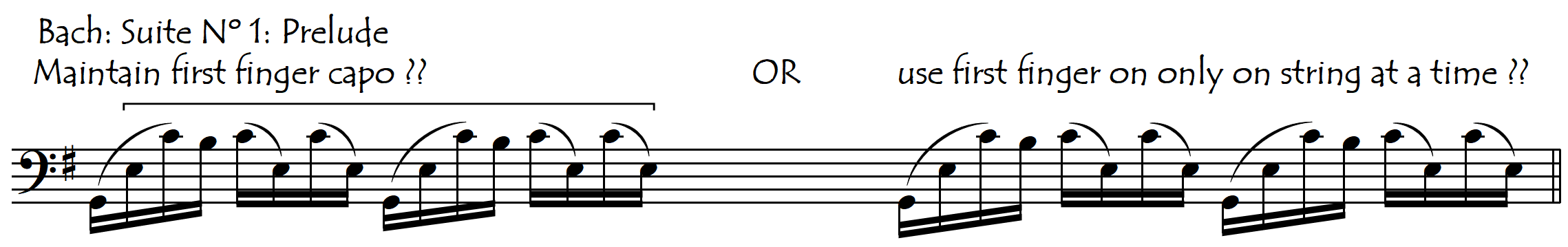

Think about the beginning of the Preludes of Bach’s First and Fourth Solo Suites. In spite of the fact that there is not even one chord played as such, this is very harmonic, vertical writing.

This music is made up of broken chords and broken double-stops, which are in fact much more frequent than the “real” ones. Although no chord or double-stop is played with the bow in these examples, the left hand is required to either operate on two strings at once (Prelude Suite I) or to leap around between the different strings like a jumping bean (Prelude Suite IV). This requires almost as much Left Hand Horizontal String Crossing skill as playing “real” chords and double-stops. We say “almost as difficult” because when the chord is broken (for the bow) it does also usually give the left hand a little bit more time than when all the notes have to sound simultaneously.

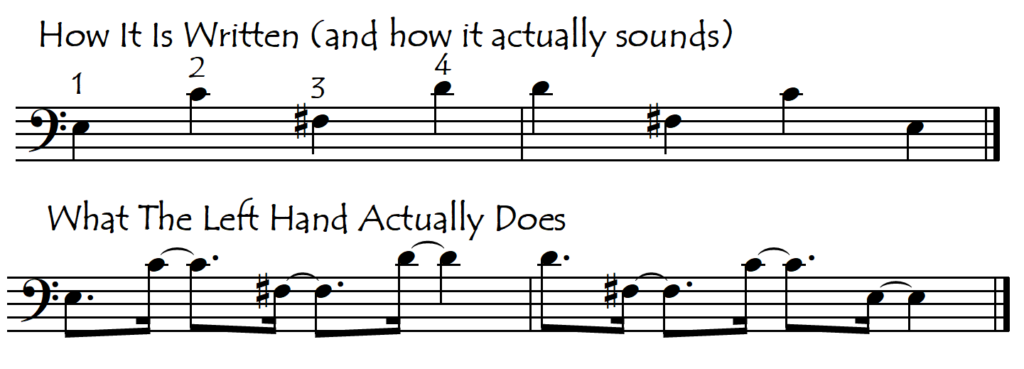

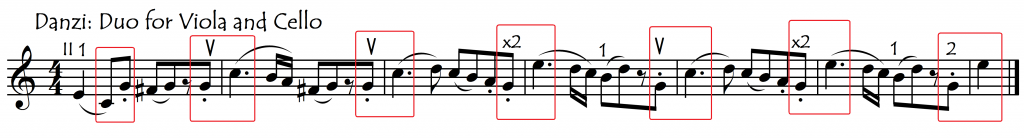

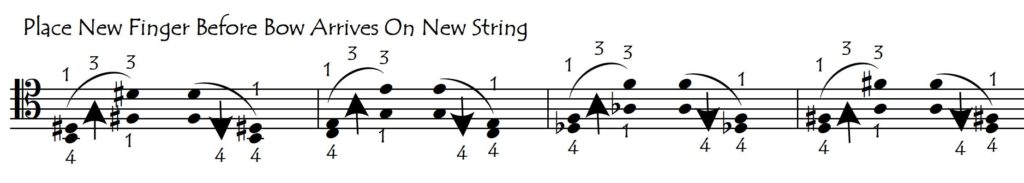

This is not always the case with broken stops however. Sometimes – especially in faster passages – even when the chords are sounded (played) “broken” by the right hand, the left hand will play them as if they were real, simultaneous chords, with the fingers all going down on the different strings at the same time:

The music of Bach – especially the Solo Cello Suites and the Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (transcribed for cello) – is full of this “harmonic” writing, using “broken” chords and “broken” double stops but also many “real” (simultaneous) double stops and chords. Thus, as well as being beautiful music, it is also excellent study material for the Left Hand String Crossing skills needed to play, understand and memorise “vertical, harmonic” music. Some of the best exercises for developing this skill can be found in Christopher Bunting’s “Essay on the Craft of Cello Playing” in which a whole chapter is dedicated to this subject. The Piatti Studies and Duport Studies Nos. 1, 14 and 16 are also useful in developing this skill as they use large amounts of double stops and chords.

Playing and practicing broken chords and double-stops is a good preliminary step in developing our sense of Left Hand String Crossing (geography and technique), the culmination of which is the ability to be able to place (and then operate) different fingers simultaneously on different strings. This culmination is reached in pizzicato chords. Here we not only have to place several Left-Hand fingers on several strings at the same time but also need to simultaneously do the same with the Right-Hand fingers (unless we are doing a guitar-type “strum”). This is perhaps the greatest test for our Horizontal Positional Sense for both hands.

CHANGE STRING OR USE “CAPO FIFTH”

Sometimes it is not absolutely clear whether it would be better to jump the finger across the strings or use the capo technique (see Fifths), as in the following example:

ANTICIPATION OF LEFT-HAND ARTICULATION ON NEW STRING

Anticipation is one of the most important and useful concepts in Lefthand Stringcrossings.

In “real” doublestops we need to maintain the fingers simultaneously on the different strings. But this doesn’t always mean that we have to place both fingers on the two strings at exactly the same time. It is often easier to place the fingers one at a time (if we have time to do this preparation of course). In broken double stops (and broken chords) we have even more possibilities to choose from with regard to the timing of the finger placement both in relation to the other fingers and to the bow. We can choose to place the fingers either simultaneously or consecutively (successively), and we can also choose when to place them with respect to the bow (or pizzicato pluck): placing them either simultaneously with the bowstart or before the bow starts to play the new note (finger). Placing the finger before we actually need it is a very useful skill and is also a very good example of the general usefulness of the Anticipation Principle.

It is useful to place the new finger on the new string before we need it because, in a string crossing, having the new finger already prepared on the new string eliminates the need for exact coordination between the hands at the moment of the bow crossing. This allows us to dedicate our entire attention to the bow at this delicate moment. Now we only need to coordinate/synchronise two elements (bow crossing with the rhythm) instead of having to coordinate three things (bow-crossing, left-hand articulation and rhythm).

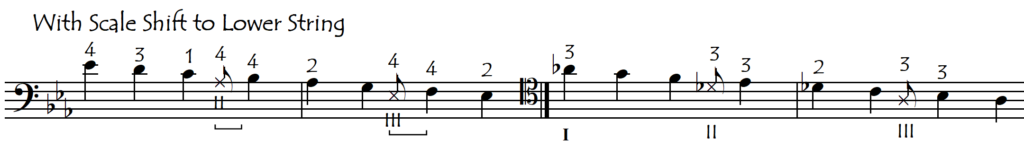

In the above example, the anticipation of our finger placement on the new string was favoured by the presence of the open string just before the new finger. The open string gives us lots of time (and lefthand brain space) to enable us to place that finger anticipatedly and with ease. This is why this skill is most easily learned initially by playing downward scales across the strings in keys that use the open strings:

This anticipated placement of the new finger on the new string not only makes fast passages easier and legato string crossings smooth, but also gives us more control in delicate bow landings from the air.

ANTICIPATION BEFORE SHIFT TO NEW STRING

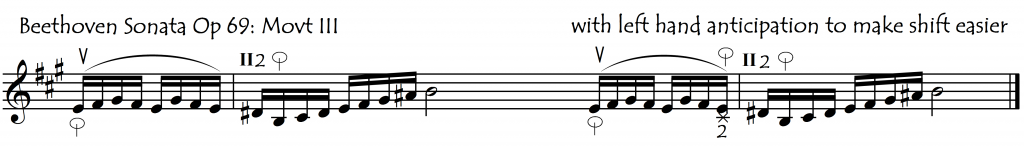

Another use for anticipated Left-Hand-String Crossings is to prepare for a shift to a new string. If we place the new finger down on the new string before we do the shift, then that is one less thing to do during the shift, which makes the shift easier because, just like for anticipated finger placement in one position (without shifts), this removes the difficulty of having to perfectly coordinate the bow’s change of string with the finger’s articulation.

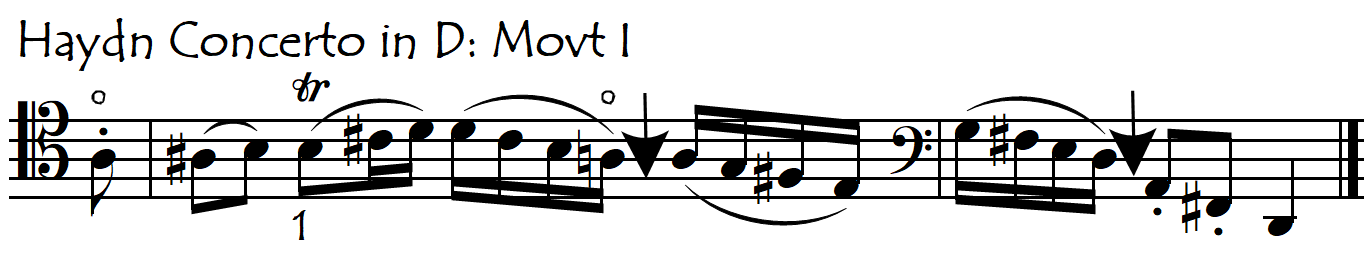

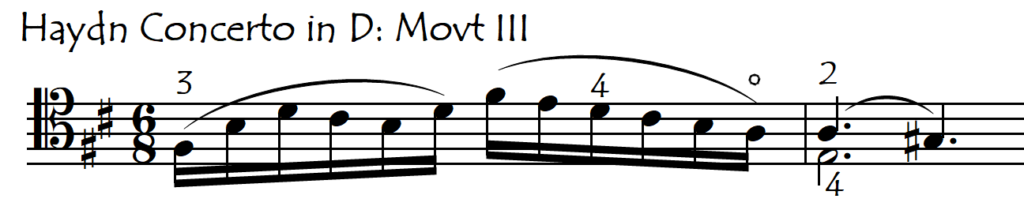

This can be especially useful in fast passages:

But it is also very useful in smooth slurred legato string-crossings, where this anticipated finger placement allows us to hear the glissando into the new position.

For more discussion about this subject, as well as practice material for working on it, see the following article:

Shifting To A Different String

DIFFICULT FINGER COMBINATIONS: HIGHER FINGER ON LOWER STRING WITH LOWER FINGER ON HIGHER STRING

Using a higher finger on a lower string while simultaneously using lower fingers on the higher strings tends to require that the hand and arm align themselves in what we have called the “Double-Bass Hand Posture” (in contrast to the “Violin Hand Posture). Compare the relative comfort of the following two hand postures:

Because the fourth finger is so much shorter than the other fingers it requires the greatest repositioning of the hand and arm in order to place it on the lower strings. Therefore the most awkward finger grouping for the Neck Region is the 3-4 combination (3rd finger on the top string and the 4th on the lower string). For the Thumb Position, the most awkward combination is the equivalent position: with the third finger on the lower string and 2# on the higher. And if we need the extended back first finger the discomfort is even worse. Often we will avoid these types of fingerings:

The following exercises are absolutely horrible to play – difficult, uncomfortable and often very dissonant – but they are very good for working on this type of problem:

Doublestopped Exercises For Higher Finger On Lower String

LEFT-HAND STRING CROSSING STUDY MATERIAL:

Placing one finger squarely (perfectly centred) on the correct string is the most basic, simple test of our lefthand’s horizontal positional sense. When we place more than one finger on more than one string at the same time, we are testing (and developing) this skill in a much more intense and challenging way.

Therefore, doublestops and chords are some of the best material for working on this department of left-hand technique. Below are some links to this type of material using 2, 3, and 4 strings. Progressions (sequences) of doublestops and chords can be played with a wide variety of bowings and rhythms with both pure and broken doublestops (or arpeggiated chords).

1: ACROSS TWO ADJACENT STRINGS

Doublestopped trill exercises, in general, are extraordinarily good at developing this skill as well as training our fingers to be independent from each other in every sense. These stay in one position so are a very “pure” way to isolate our LH string crossings as we have no shifting to worry about::

Doubletrill Exercises In One Position: NECK REGION Doubletrill Exercises In One Position: THUMBPOSITION

Piatti’s Caprice Nº 1 Op 25 is an excellent study that works almost exclusively with broken doublestops across two strings. It combines the precise technical focus of the exercises with the pleasant harmonies of a musical composition:

On the cellofun.eu page dedicated to chords and doublestops can be found compilations of repertoire excerpts in doublestops, grouped according to the historical period. This is excellent material for working on our left-hand’s horizontal sense.

2: ON THREE AND FOUR STRINGS

Placing Fingers on Three or Four Stringers Simultaneously: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS