Simple Extensions on the Cello In All Of The Fingerboard Regions: Different Extended Hand Postures

On this page, we will look at our simplest extensions: those of a major third between the first and top fingers (with the corresponding whole tone normally between the first and second fingers). These general observations are in principle, valid for all the fingerboard regions (Neck, Intermediate, and Thumb).

EXTENSION LABORATORY

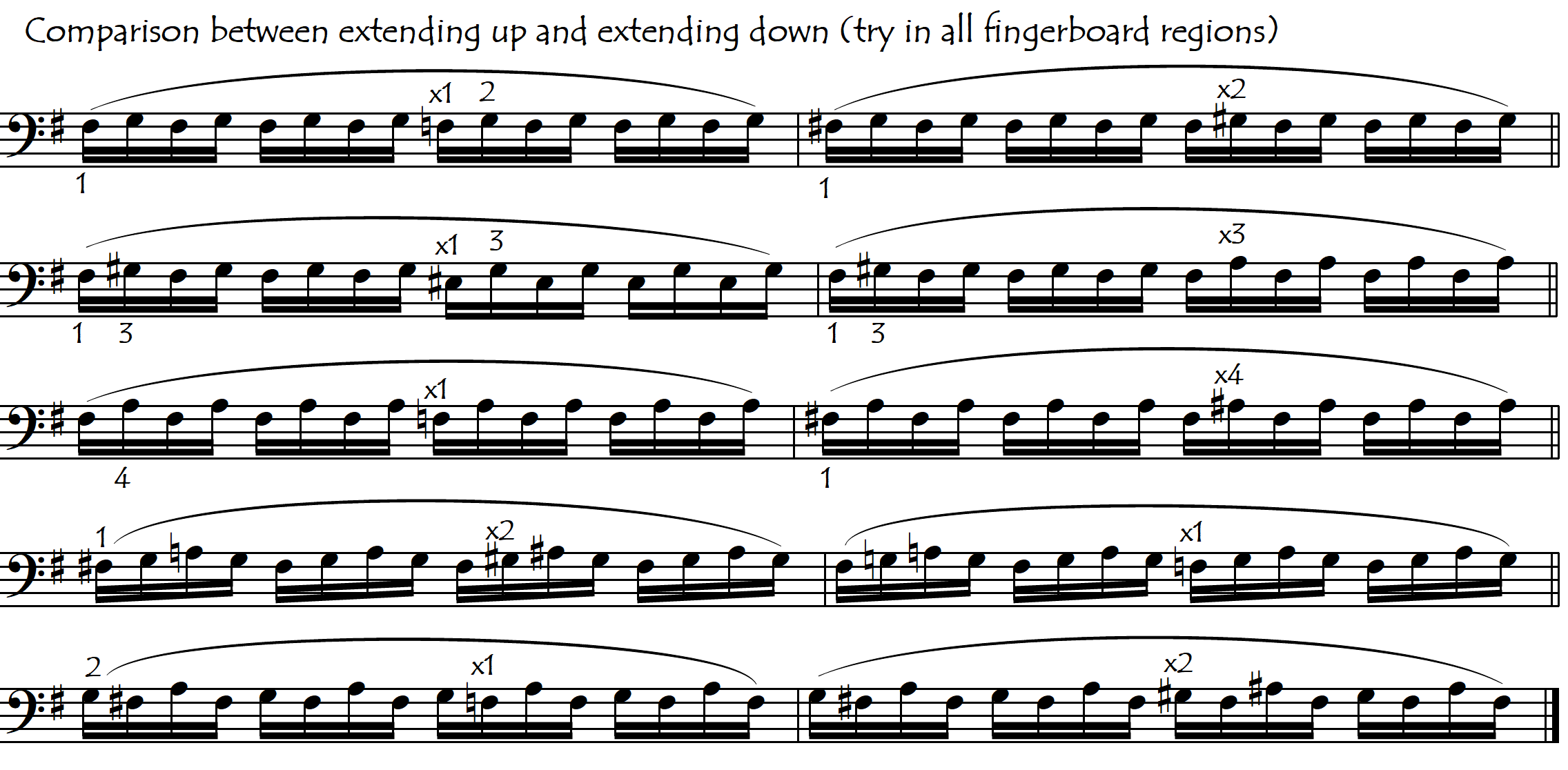

Before we start any “talking”, try playing the following little note sequences, observing the whole time just what the differences are between the upwards and downwards extensions and what the different elements of our left hand and arm want to do in order to make the extensions comfortable:

- what does the thumb want to do: move ? be released ?

- how curled (curved) are our different fingers in the extensions ?

- what do we do with our wrist, elbow, shoulders, and even our neck ?

The note sequences are shown only in the neck region but we can transpose them up into the intermediate and thumb regions also.

To make an extension we have a choice of hand posture/position that will be somewhere between the two following extremes, depending largely on our hand size, cello size, position of the thumb, and relative finger lengths:

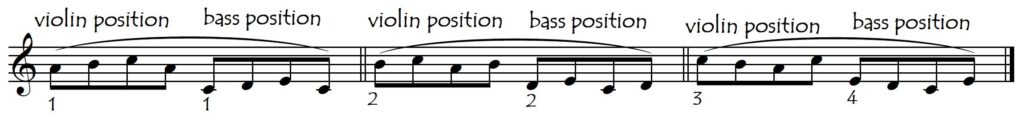

1. VIOLIN HAND POSTURE:

In this position, the hand is sloping  backwards towards a very curled (rounded) first finger. The wrist is flat (as though it were the direct continuation of the forearm), the highest finger is quite straight (extended) and the thumb is touching the back of the cello neck quite deeply (in the Neck Region). This position can be considered as an extension upwards by the higher fingers. In this position, the first finger is the strong, stable, unchanging base from which the higher fingers are extended (strained). To help this extension, it is useful to allow the metacarpal (knuckle) joints to “collapse”, especially of the first finger. This gives the back of the wrist a concave shape (“caved-in”). It is as though we were reaching up to the higher note from “underneath” (see below)

backwards towards a very curled (rounded) first finger. The wrist is flat (as though it were the direct continuation of the forearm), the highest finger is quite straight (extended) and the thumb is touching the back of the cello neck quite deeply (in the Neck Region). This position can be considered as an extension upwards by the higher fingers. In this position, the first finger is the strong, stable, unchanging base from which the higher fingers are extended (strained). To help this extension, it is useful to allow the metacarpal (knuckle) joints to “collapse”, especially of the first finger. This gives the back of the wrist a concave shape (“caved-in”). It is as though we were reaching up to the higher note from “underneath” (see below)

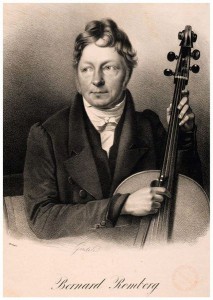

The illustration on the right shows the cellist Bernard Romberg (1767 – 1841) with his hand very exaggeratedly in this position. Janos Starker favoured this position as did also, it would appear David Popper. There are two main advantages to using this hand posture for extensions:

- it facilitates vibrato

- it is the same in all the three fingerboard regions, thus facilitating rapid, comfortable and secure shifting between regions.

The main impediment to using this position in extensions, especially in the lower neck region but also in the higher regions, is that the highest finger – especially the 4th finger in neck position – is simply not long enough. Cellists with long fingers – especially the higher fingers – have a great advantage and will be able to use this very practical “violin position” more than cellists with short fingers.

2. DOUBLE-BASS HAND POSTURE:

We are obliged to use this position if we can’t reach an extension using the “violin posture”. Whereas in the “violin posture” it was the higher fingers that were extended (straight), in the “double-bass posture” we can consider the extension as an extension downwards (backwards) of the first finger, which is now straighter, or even completely straight.

In this posture, the hand is flatter, with the back of the wrist not sloping backwards but rather more square to the fingerboard, or even maybe sloping forwards (upwards) towards the higher fingers which are “curled” (rounded, not straight). The wrist-joint is often raised up in relation to the fingers and forearm, especially for small-handed cellists. To make the stretch even bigger or to reduce the tension in the hand, we may release the thumb from its contact with the neck. Doing this is a little like standing on only one leg to be able to reach a little higher.

In this posture, it is as though we were reaching “up and over” to the top finger (whereas in the violin posture we were reaching up to the top note from “underneath”). Using this “double-bass” posture we can reach further than with the “violin” posture however this greater reach comes at a price. The price is that this is a less stable and less comfortable posture than the “violin posture”, especially with respect to the extended-back first finger, which is fundamentally unstable when it is under tension (for small hands). Vibrating on, and shifting from and to, this stiff, straight, rigid, extended-back first finger is difficult for the small-handed cellist and is often a cause of bad sound and insecure intonation. For large-handed cellists however, the extended-back first finger is less strained and rigid than for a smaller hand, and the finger can even maintain some of its healthy curve. This posture was favoured by both Andé Navarra and Paul Tortelier.

In thumbposition, this posture is not practical unless we have a very long thumb or unless we release the thumb from its position on the fingerboard. In “fourth” position on the A string, this hand posture is not practical either, because the pinky (little finger) side of the hand collides with the edge of the top of the cello. Therefore we need to use the violin position in these areas.

CONSEQUENCES OF CHANGING THE HAND POSTURE:

Changing between these two hand postures is awkward and constitutes a source of difficulty, tension and intonation problems. If these hand-posture changes occur during shifts they can add considerable insecurity to the shift. In slower music we will have time to adjust to our new hand posture before the shift starts, after arriving at the new note, or even during the shift. In rapid playing however, those hand-angle changes can be very disturbing which is why, during fast passages, we need to try to have as much stability and consistency in hand posture as possible. Popper’s solution to this problem (as well as Starker’s) was to keep the left hand as much as possible in the “Violin Posture” in all regions of the cello fingerboard. This however requires a long fourth finger for the lower regions. Tortelier’s solution was to stay as much as possible in the “Bass Posture”, which however requires a long thumb for the higher regions.

The fact that in the Intermediate and Thumb Regions we normally use the Violin Position whereas in the lower Neck Region we will normally use the “Bass Posture”, means that in faster shifting passages between the Neck Region and these higher regions, to avoid the disturbing hand-angle change, it is useful to use the Violin Position also in the Neck Region. One way to achieve this is by using fingerings that avoid extensions (and therefore avoid the use of “Bass Posture”) in the lower Neck Region on either side of (before or after) rapid or difficult shifts between the regions.

Fortunately, these shifts between regions are often quite large, and this big shift size reduces the disturbance caused by our hand posture change simply because we have a longer distance over which to achieve it.

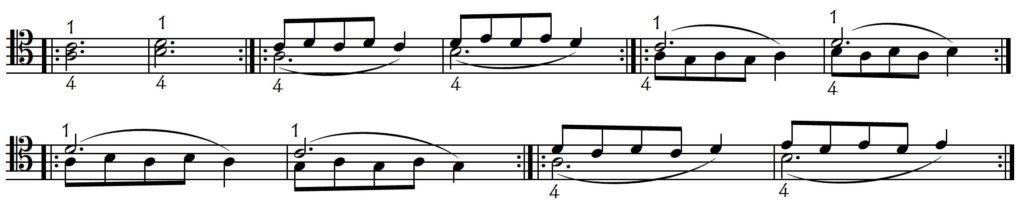

Perhaps the most disturbing postural change between “Bass” and “Violin” extended postures occurs for small-handed cellists over a small distance in the Neck Region on the higher strings between the extended-up third position (bass posture) and the extended-back fifth position (violin posture) as shown in the following example. Here, over a very small distance, we have a large (and very destabilising) hand-angle change. This makes scales in thirds quite awkward:

This postural change is made unavoidable because the side of the cello obstructs the forearm and hand from continuing their upwards trajectory in the “doublebass position”. This obstruction is most significant when we are playing on the higher strings because it is on those strings that our forearm and elbow are held the lowest. Because of that low elbow (which is necessary to enable us to play on the pads of our fingers), our arm hits the side of the cello as we go up the fingerboard (towards the bridge) unless we either raise the elbow (very awkward for the playing fingers) or change the hand angle into the “violin position”. We can consider ourselves lucky that, just at that moment when the arm can go no further in the “bass position”, the distances between the fingers become small enough that we can, for the first time, reach the 1-4 major third with the hand in the “violin position”.

For larger and/or more flexible hands this problem is much reduced and may even be inexistent.