Shifting On The Cello (or on any string instrument)

“Shifting” is a huge subject so it has been broken up into several different pages. On this page we will discuss some general concepts concerned with shifting, but other more specialised aspects of shifting have their own dedicated pages (click on the highlighted links).

- Finger Choreography

- The Glissando: Expressive Tool and Technical Aid

- Non-Whole-Hand Shifts

- Shifting and the Bow

- Shifting To Another String

- Shifting During an Open String

The most basic discussion of how we know where our left hand is on the fingerboard is dealt with on the page:

WHAT IS A SHIFT? DIFFERENCE BETWEEN “SHIFTS” AND “PLACEMENTS”

If we ask the question “what is (and what isn’t) a shift“? our logical first reaction is probably to think “duhhh …… what a stupid question“! But is it really such a stupid question? Finding a note in a new position is always the result of a displacement of the left hand, but this displacement is not always what we would consider a “shift”. When, for example, we start a piece (or when we find our new position after a long rest), we don’t normally consider that we are doing a “shift” but rather that we are “finding our starting note”. We will call these note-findings “placements” to differentiate them from “shifts”. So what is it then that determines the difference between a “shift” and a “placement”? There seem to be three interrelated factors involved in making this distinction, and it is these three factors that will determine whether we do our hand displacement in one or the other way:

- the amount of time pressure we are under when finding our new position

- the possible use or not of sliding left-hand finger contact with the cello during our approach to the target note/hand position. If we slide into our target position then we can consider this hand displacement as a shift. If, on the other hand, the hand doesn’t slide into its target position, then we can consider that this is a simple “finger placement” (or “note finding”) rather than a shift

- the relevance of the “departure note” to finding the position of the “destination note”.

These three factors are closely related, because it is when we have no time pressure (i.e when we have loads of time to find our new position), that we are most likely to release the contact of the fingers with the fingerboard in the gap between the two notes and thus do a “placement” rather than a “shift”. We do this in order to allow the hand and arm to rest. Taking every reasonable opportunity for rest is an absolutely normal, spontaneous and healthy reflex that we do instinctively not only with both arms at the cello but also with our entire body in everyday life. It is this same instinct that leads us to normally want to sit down when it is no longer necessary to stand up. However for our arms, taking opportunities to rest is even easier: sitting down requires a chair, whereas we don’t need any object on which to rest our arm(s).

When our left hand comes to the fingerboard from its resting position, we rarely use a slide (audible or inaudible) to find our new note. This is why we call this way of finding a new position a “placement”. When finding a note in this way we almost always first place the thumb in its position under the cello neck (or on the fingerboard if we are in thumbposition), and only then do we place the finger, often checking its pitch of the note with a soft left-hand pizzicato before actually playing it. In this process, rather than finding our new note with a shift, we are now finding it “out of the blue”, “from midair”, which makes more demands on our absolute positional sense than on the relative positional sense that we use when measuring distances. Finding a note in this way can be considered as a “fresh start”, or a “new beginning”, for which the previous note is often almost irrelevant. In these cases, our hand displacements up and down the fingerboard can be considered “placements” rather than “shifts”.

To summarise, we basically have two standard situations for finding new left-hand positions (notes):

1: lots of time to find new position = find note from the air (from the rest position) = no slide = placement (and not a shift)

2: with time pressure = not enough time to rest the hand = maintain finger contact with fingerboard during displacement = a shift

HOW DO WE DECIDE WHETHER TO DO A “SHIFT” OR A “PLACEMENT”

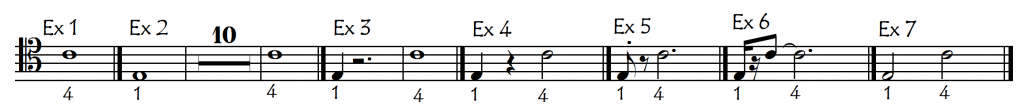

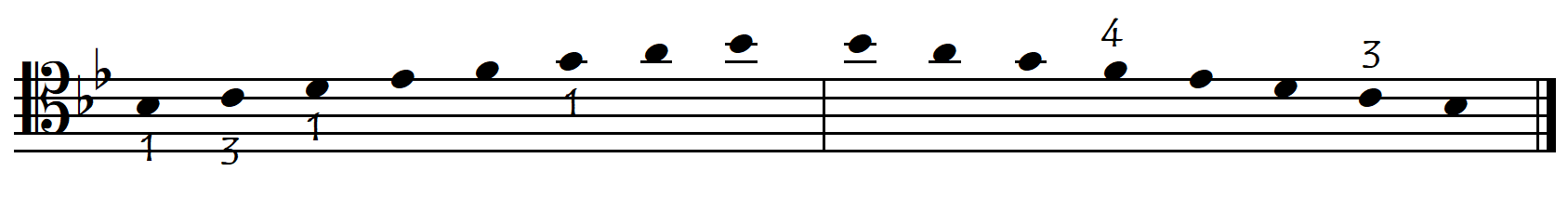

Normally it is simply the amount of time pressure we are under that will determine whether we will use a “shift” or a “placement” to find our new position. Let’s look now at some different practical examples of this. In the following progression of examples, the amount of time we have to do our identical hand displacements is progressively reduced. Which of these seven placements of the fourth finger “C” on the D-string would most likely be the result of a “shift”(with a slide), and which would most likely be the result of a “finger placement” (no slide):

While all of these “findings” of the 4th finger on “C” could be achieved by shifts, it is only Ex 7 that absolutely has to be done by a “shift”. In all the others, the fact that there is some “free-time” before the left-hand displacement means that the fingers and/or the whole hand could be removed from the fingerboard during the rest, and thus the fourth finger could be found by a placement rather than by a shift. The less time we have to do the hand displacement, the more likely we are to do it with a shift (maintaining finger contact with the fingerboard).

Let’s look at these examples now in more detail:

- in example 1 we are finding our first note “out of the blue”, from our left arm’s resting position. This is the way we start a piece, and it would be highly unusual that we might want to find our starting note by means of a shift.

- in example 2, we have so much time to wait between the two notes (10 bars) that we will certainly allow our left arm to relax entirely, taking it and the hand away from the cello neck. This means that when we come to play the second note of this example, it is as though we were starting the piece “from zero” exactly like in Ex 1. The first note is long “forgotten” and no longer relevant to finding the second note. Once again, it is highly unlikely that we might want to use a “shift” to find this note.

- in examples 5, 6, and 7 we can leave the “old” finger on the string during the rests and thus do the hand displacements as “shifts”. Alternatively, we could, if we wanted to (or needed to scratch our nose), remove the left hand entirely from its cello contact during the rests and then find the new note “out of the blue”. [Aha! this is why rests are called rests]

To recapitulate: our choice between hand removal from the cello (followed by a placement) and hand remain (shift) will be determined mainly by the amount of time that we have between the origin and target notes (or by the urgency of our itch). For example, in the transformation occurring from example 5 to example 7, we have progressively less time in which to remove our hand from the cello neck. At some stage, removing the hand for a rest (or a scratch) will no longer be feasible and/or worthwhile, because the effort and rush of having to do it so quickly and for such a short time is greater than the benefits obtained.

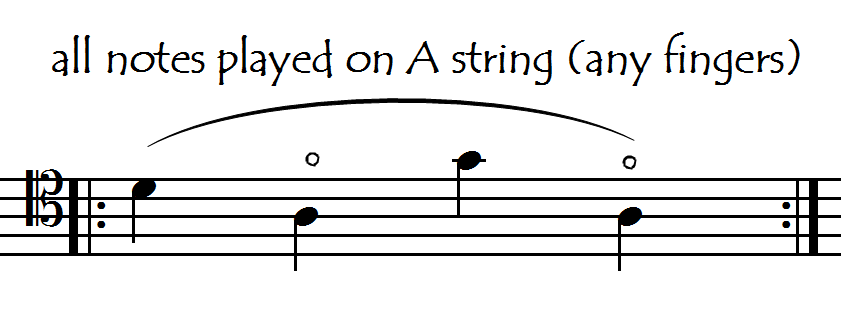

A SPECIAL CASE: SHIFTING ON THE SAME OPEN STRING

Shifts during the same open string are quite unique in the sense that the left-hand fingers must be released from their contact with the fingerboard during the shift in order for the open string to be able to sound. Therefore there is no possibility of using a slide (glissando) – audible or not. So in fact, they are more like “placements” than shifts. These placements are however more difficult than our normal placements because there is no possibility of putting the finger down before it is needed (to check its correct location). This is why these “shifts” are particularly difficult and have their own specific page (Shifting On The Same Open String).

SHIFTING: ORDER OF DIFFICULTY

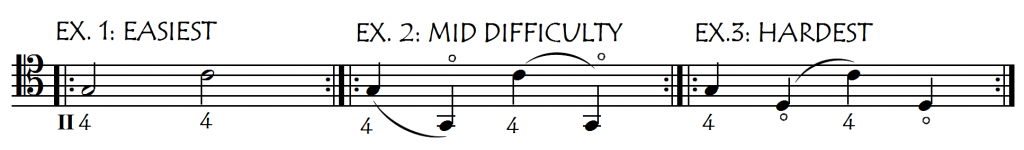

We can establish an order of progressively increasing difficulty for shifts, based on the concepts discussed above. The easiest shifts are those in which not only do we have permanent finger/string contact throughout the shift, but also we can hear the glissando (Ex. 1 below). If that permanent finger contact is however inaudible (normally because the bow is on another string) then the shift becomes somewhat more difficult to control (Ex. 2 below). The hardest shifts of all are those in which we have no finger contact during our hand’s displacement, such as occurs when shifting on the same open string (Ex. 3 below). In the following examples, for an identical hand displacement, the shift difficulty changes, increasing from Ex 1 to Ex 3, according to these principles of finger contact and shift audibility.

These concepts are developed in the different pages dedicated to the specific aspects of shifting, but the link below opens a “Shifting Laboratory” page in which we can do any shift in a progression of increasing difficulty with respect to the contact of the fingers with the string and the audibility of the glissando:

SHIFTING: AN EXPRESSIVE DEVICE OR A TECHNICAL PROBLEM?

Depending on the musical context, shifting – moving the hand and arm up and down the fingerboard to find a new note – can be considered either as a technical problem to be overcome (as discreetly as possible), or as an expressive opportunity to be exploited, and sometimes as both. This very often depends on the speed of the music we are playing.

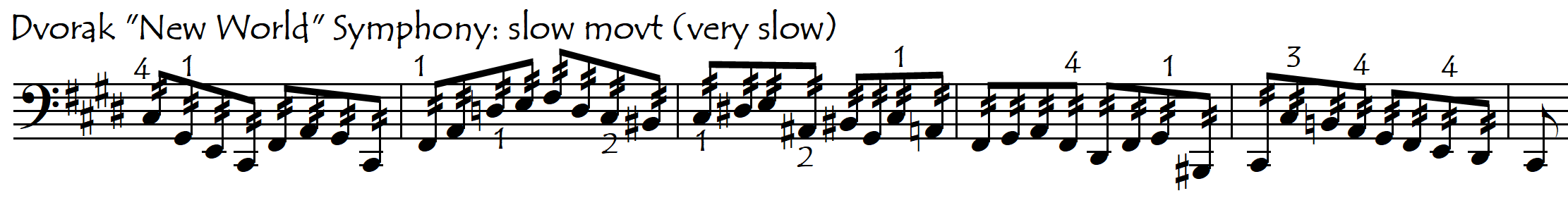

In slow music we will often use our shifts as expressive devices, trying to stay as much as possible on one string so that we can make vocal glissandos (see Expressive Fingerings). In fast music we will tend to do exactly the opposite, trying to avoid shifts (most notably by going across the strings instead of staying on the same one), and hiding those shifts that are unavoidable (purely technical rather than expressive – see Technical Fingerings). A glissando can sound like a muddy smear in a fast virtuoso passage where brilliance and machine-like perfection are the expressive goals. (examples)

ESSENTIAL TECHNICAL TIPS FOR SHIFTING

There are a few fundamental principles (“tricks”) that can help us to achieve fluid, easy, smooth and accurate shifting:

- shift as slowly as the music allows

- anticipate the shift with a preparatory arm movement

- keep the hand as relaxed as possible before, during, and after the shift (avoid shifting in extended position)

- relax the pressure of the shifting finger on the string during the shift, except for when we want an audible legato glissando

- understand the utility of the “intermediate note“

Let’s look now separately at these vital elements of shifting.

1: SHIFTING AS SLOWLY AS POSSIBLE: THE SPEED AND TIMING OF SHIFTS

When we give ourselves more time in which to do a shift, then we can do it more slowly, with more ease and comfort. There are two main ways in which we can give ourselves more time:

- start the shift as early as possible and

- use fingerings that place the shifts after longer notes.

Let’s explain these two principles, for which the following example serves as a good illustration:

1A: THE IMPORTANCE OF AN EARLY DEPARTURE

Musical notation does not allow for the time it takes to do a shift. In a literal interpretation of musical notation, any shift (that is not done during a rest) would be “infinitely fast” in order for us to be able to both hold the note-before-the-shift to its full value, and also start the note after the shift in time (see Problems Of Musical Notation).

This problem doesn’t occur at all for computers and is much reduced for keyboards (thanks to the sustain pedal) and for wind instruments (because the hands don’t move, only the fingers). But on string instruments, we often have to move our hands through large physical distances, and seeing as we have no sustain pedal, we have to steal the time for these shifts from somewhere. Unwary, honest, obedient string players, who don’t like to steal, and want to play the rhythms exactly as they are written, may therefore think they need to do their shifts both as-late-as-possible and as-fast-as-possible. This is a recipe for disaster in every sense and absolutely the opposite of what we need to do.

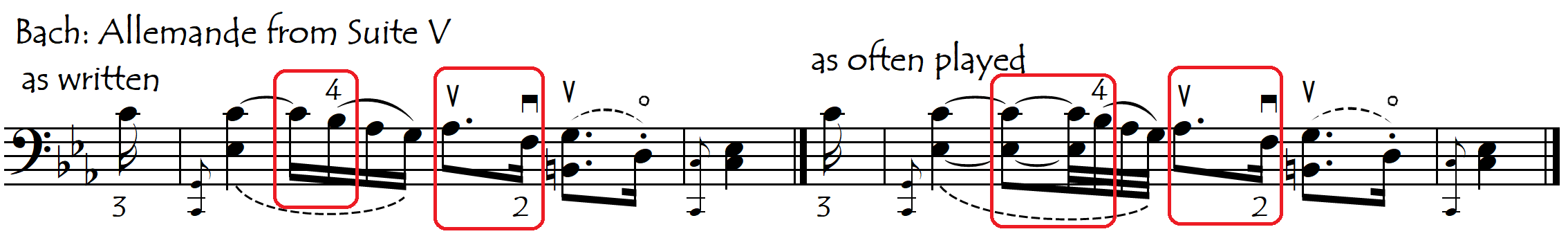

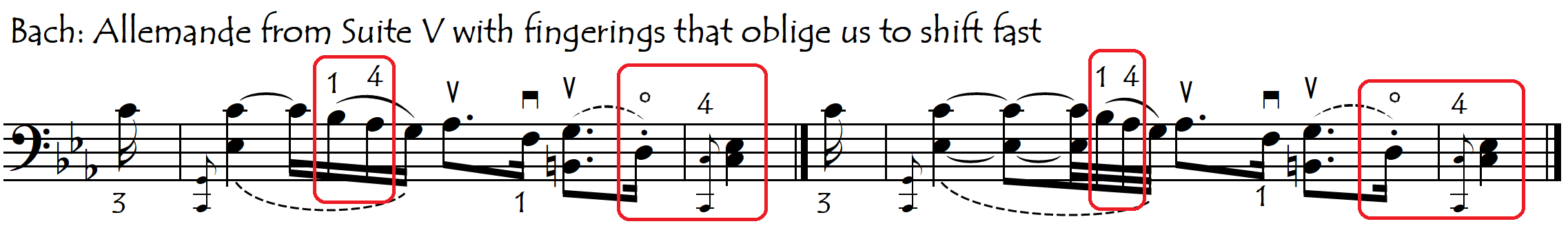

So where do we steal this “shift-time” from? The answer is that we steal the time for the shift almost always from the end of the note preceding the shift. In other words, we shorten the note before the shift in order to be able to do the shift and still arrive at the exact correct moment on the next note. In the above example from the Bach Allemande, this task is made easier because the notes on either side of the shift have a musical separation between them (they are not slurred). When can use this separation the time in which to do our shift: comfortably and without any hurry. Gary Hoffmann likes to start with the general idea that we should use half the time (duration) of the last note for the shift. Or, to put it in other words, that we should shorten the note preceding the shift by half, and use the second half for our shift.

There are of course exceptions to the rule. In some special cases, where the shift itself has an expressive or dramatic effect, we can take some (or all) of the time for the shift from the arrival (“new”) note by delaying it.

It is a fundamental principle of healthy shifting to shift as slowly as the music will let us. But shift speed is inextricably linked to shift timing. In order to be able to shift slowly, we need to start our shifts early. The earlier we start the shift, the more time we will have to get to our destination, and the more fluid, flowing, relaxed and easily controlled will be not only our voyage but also our arrival. It is the musical context that determines how early is too early, and how slow is too slow.

Conversely, the later we start the shift, the faster we will have to shift in order to arrive on time. A shift that is started late has thus every chance of being a frenzied, tense, panicky jerk. Its speed and abruptness make it difficult to control, especially at the arrival point where the sudden braking makes the correction of arrival intonation difficult.

PIZZICATO AND TREMOLO: TWO DIFFERENT WAYS TO SLOW OUR SHIFTS DOWN

When we play pizzicato, each note gradually fades away because there is no motor (bow) to keep pumping energy into the sound. This allows our left-hand to relax between the notes and gives us lots more time to do our shift, as well as giving us more brain-space to observe what is going on between the notes. This is why playing a passage pizzicato (at a slow or moderate speed) can be a very useful way to work on our shifting: it is like watching our shifts in a slow-motion video. We can observe our shift speed in any passage, playing it alternately pizzicato and bowed (both slurred and separate bows).

Another great way to get used to shifting smoothly and relaxedly, with early shift-departures, is to play our passages with tremolo bowing. Because it’s impossible to do our shift during “the bow change” we can now relax both hands totally and make the shift a beautifully smooth organic movement. Not only does the bow tremolo encourage us to shift very ergonomically with the left-hand but also we learn, almost automatically, to relax the bow pressure during the shifts so as to dosify (calibrate) the audibility of the glissando (see Shifting And The Bow).

1B: FINGERINGS TO GIVE US MORE SHIFTING TIME

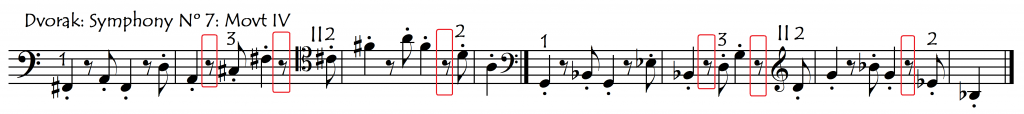

When all the notes are fast, we will have to shift fast, but when only some of the notes are fast we can very often can choose our fingerings according to the rhythm of a passage, in such a way as to give us the most time possible for the shifts. When the note preceding a shift is a “long note” it is easier to steal time for the shift than when the shift comes after a “short note”. In other words, it is usually a good idea, especially in faster passages, to do our shifts and string crossings before the short notes (= after the long notes), because that is when we have the most time. Immediately after the short note is when we have the least time, so any movement done after the short note will have to be done quickly (see Fast Playing). For this reason, dotted rhythm passages often benefit considerably from a little more thought as to which fingerings to use. Using “standard” fingerings, and/or shifting “only when we need to” (at the last minute) can cause us to get tangled up.

The Bach Allemande example can give us a good illustration of what happens when we finger a passage “badly”, with the shifts after the short notes instead of after the long notes. Suddenly we have no time for our shifts and they have to be done fast, with a corresponding increase in tension and difficulty:

In the following scale passages, even though the sequence of notes is identical in the three examples, we need to do a different fingering for each one if we want to avoid unnecessary “panic” shifting. Of course in sight-reading, we may not have time to work out the most ergonomic fingering, which is why sight-reading difficult music can be quite unrewarding.

The repertoire is full of examples where we can put this principle to good use. It doesn’t only concern dotted rhythms: we simply want to shift where we have the most time. In the repertoire example below, by shifting on the rests (as indicated) we are giving ourselves much more time to do the shifts than if we were to shift after the short notes.

Many more examples in which we can apply this fingering principle can be found in the pages dedicated to Dotted Rhythms.

Many more examples in which we can apply this fingering principle can be found in the pages dedicated to Dotted Rhythms.

2: PREPARATORY MOVEMENTS BEFORE SHIFTS

The orange (middle light) on traffic lights was a giant evolutionary step forward. Only the most primitive systems function exclusively with a simple autistic binary logic of “yes/no” or “stop/go”. Systems that are more highly evolved, have a preparatory phase before both the “yes” (starting) and the “no” (stopping) actions. These preparatory phases make movements fluid and comfortable that would otherwise be stiff, jerky, mechanical and hurried. It is the preparation that allows this. Preparation (anticipation) makes the difference between brutal or beautiful, abrupt or flowing, hurried or easy, tense or relaxed etc, and shifting is a very good illustration of this rule.

Doing a shift is like putting a car into motion. To achieve a gradual, smooth, controlled, comfortable release from our starting position we need a clutch. For a cellist’s left hand, the “clutch” involves preparatory movements along the whole arm, shoulder and possibly even the back. When these movements become totally automated and natural, we no longer realise that we are doing them. At this stage we can consider that our clutch has evolved into an automatic gearbox!

Normally it is the upwards shifts that require the most conscious preparation. This is because in the lower positions the left arm is closer to the body, and feels more “at home”. Bringing the hand to the higher positions and keeping it there requires more muscular effort than going in the opposite direction because in the higher positions the arm is extended and the elbow is raised, all of which requires effort. Coming “home” is always(?) easier than preparing a voyage to faraway territories and it is as if by simply relaxing the arm, that it falls gently and effortlessly back down to earth.

The most important anticipatory movement concerns the elbow (sometimes accompanied by the shoulder) which needs to be raised before a shift up the fingerboard. In Scale-Arpeggio type shifts (see Shift Types), the contraction of the hand (see below) which anticipates the change of finger, will also be part of the anticipatory movements before the shift. Placing the destination finger on the destination string is also an important part of our shift preparation.

It is this preparation that allows us to make even enormous fast shifts seem fluid and easy.

3: KEEP THE HAND AS COMPACT AS POSSIBLE DURING SHIFTS

If we allow our fingers to bunch up together before the shift (rather than staying in our normal slightly extended playing position with one semitone distance between each finger), then this allows our hand to be not just totally relaxed but also to be at its maximum of compactness and stability. Relaxing the hand in this way before the shift encourages it to stay relaxed also during and after the shift, and this will help our shifting enormously. In faster music, we may not want to use this technique because at higher speeds this contraction may be destabilizing for our positional sense. But in slower music, not only is this technique easier to do but also it is more important to use it, because it is in slower music that we have the greatest need for both warm relaxed shifting, and for warm relaxed vibrato before and after the shift. The smaller our hand, the greater the benefits will be of using this technique.

4: FINGER CONTACT AND PRESSURE DURING SHIFTS

In the same way that tightrope walkers always maintain contact between both of their feet and the rope, it is much safer for us string players to always maintain the contact of our left hand with the string during the shift. The ideal pressure of this finger contact is simply the minimum necessary, according to the type of glissando that we want. If we want a beautiful vocal legato glissando then we will need to maintain the string more firmly stopped by the target finger during the shift. If, on the other hand, we don’t want this type of vocal shift, then the fluidity, speed and ease of our shift will be helped by relaxing the pressure of the shifting finger on the string. In other words, while finger contact is absolutely desirable in shifts, finger pressure is not an “either-or” situation: we will dosify the finger pressure during the shift according to the amount of audible glissando we want.

5: THE USE OF INTERMEDIATE NOTES

“Intermediate Notes” are notes that were not written by the composer but that we will use as a technical aid in order to help us find the new left-hand position of the note that is actually required by the composer. We use them hugely in silent placements of the hand (finding our new hand position without any audible glissando). That subject is dealt with above. In normal (glissando, sliding) shifts, intermediate notes are really only used in “Assisted Shifts”, for which they are often a vital component. Click on the following highlighted links for a detailed discussion of this subject.

DOUBLEBASS PLAYERS: SHIFTING EXPERTS

The technique and musicality of shifting are, like most aspects of string-playing, common to all string instruments, but it is doublebass players who are the most exposed to this (mine)field (or goldmine, depending on how you look at it). Their standard vibrating string length of 106-110cm compares to the cello’s 69-70cm, the viola’s 37-38cm and the violin’s 32-33cm. Not only do they have to cover huge distances but also have to shift more often because their handframe barely covers a minor third. And, to make matters even more complicated, they very often (especially in Classical Period repertoire) double the cello parts which, in fast passages, requires extraordinary shifting virtuosity. This means that it is doublebass players who, amongst all string players, tend to develop their shifting expertise and become shifting virtuosi in order to dominate their repertoire.