Notation (Reading) Problems For Musicians: Rhythm

This page is part of the article dedicated to Music-Reading and Notation Problems. A more general discussion about rhythm can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted link. Reading problems related to pitch are looked at on the following page:

Reading and Notation Problems In Relation To Pitch

******************************************************

The notation of rhythm is both simpler and more standardised than the notation of pitch. Whereas any single pitch (note) can be notated in five ways (double flat, single flat, natural, sharp or double sharp), rhythmic values are standardised. As long as it starts on the beat, a crotchet (quarter-note) is always a crotchet: it is never notated as two tied quavers (eighth-notes), nor as three tied quaver triplets nor as four tied semiquavers (16th-notes). Likewise for the other note values (8th notes, 16ths and whole notes etc).

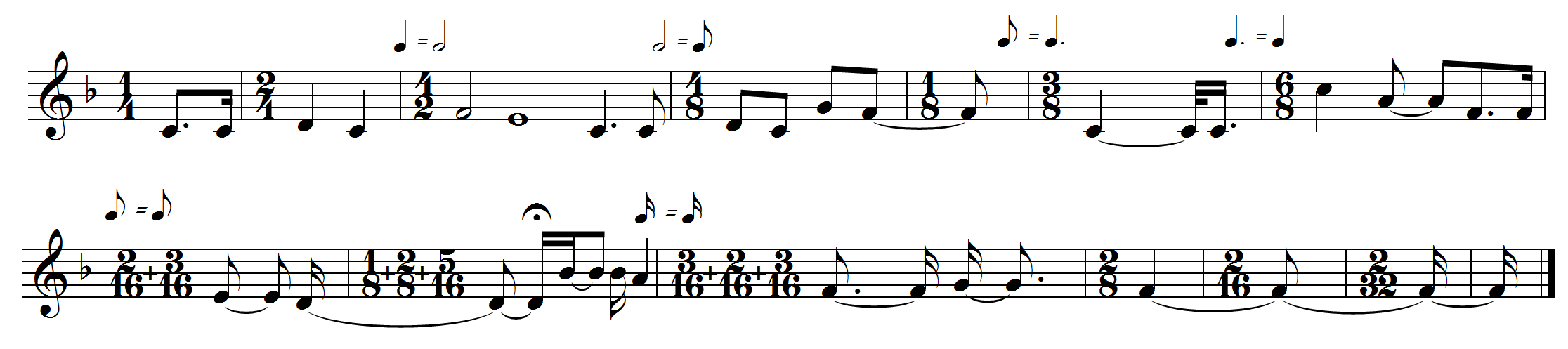

While rhythm-reading does tend to be more straightforward than pitch-reading, this doesn’t mean however that the reading of rhythms is necessarily easy: it still requires a huge amount of hours to automatise the decoding of the note values. And, as with pitch, composers, editors and music publishers can (and do, surprisingly often, especially in 20th-century music) make our job much harder than it needs to be, by using sub-optimal ways to notate their music. It is possible to make even the simplest music incredibly complicated:

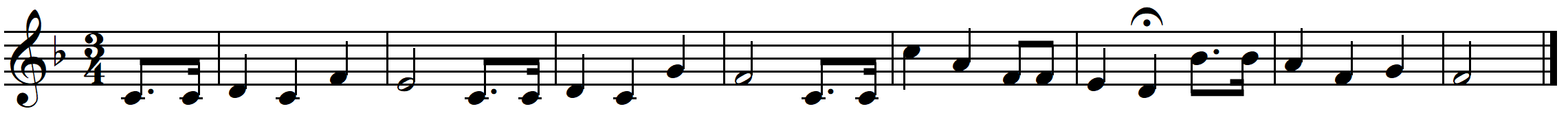

A surprisingly large number of “modern” composers love to write stuff that looks like this, perhaps to show how clever they are or perhaps because they are writing at a computer (which can read anything). They are certainly not thinking about how to make the job easier for the people who will later try to play their music. Even such famous composers as Stravinsky and John Adams (and perhaps even Brahms!) are guilty of this “crime against performers”. Very often there are alternative ways to notate, in a much more user-friendly manner, the more complex/confusing rhythmic effects that we might find in the (almost exclusively modern) repertoire, but once the music is published it is too late to find these, and all performance errors are blamed exclusively on the poor players. How much easier it could all be for the performer, with a little thoughtfulness from the composer regarding their notation choices: in the case of the above passage, for example, if it was notated :

Complications in rhythm-reading that derive from the notation can be grouped into several different types:

- time signatures and barline placements

- beaming

- ornamentation

Let’s look now at these questions one by one:

1: CHOICE OF TIME-SIGNATURES AND BARLINE PLACEMENT

When composers notate their music in a different key signature to how it sounds (see Pitch-Reading and Notation Problems) this can create unnecessary reading difficulties (depending on how far apart the two keys are). Likewise, when composers write the music in such a way that it “sounds” with a different pulse to that which is indicated by the time signature and the barlines, this also can create unnecessary reading problems for the players, this time with respect to the rhythm. This situation is relatively common in music that alternates between 3/4 and 6/8. Sometimes the composers change the time signature, other times not, but this is only the easiest example of the problems derived from “polyrhythms” because with this 6/8-3/4 alternation, the basic pulse (with the accent on the first beat of each bar) doesn’t change. Other cases can be much more confusing.

BIZARRE BARLINES IN NON-BIZARRE MUSIC

Music is never composed/imagined with barlines. The choices of time signatures and barline positions are notational decisions made after the conception of the music and although the idea of barlines and time signatures is to make reading easier, sometimes they do quite the opposite. Barlines that have no relation to the phrasing or rhythmic structure of the music can be a little like road signs that point the wrong way: not just unnecessary and irrelevant but actually a distraction, a nuisance, and dangerous traps that are better ignored. In these cases, playing by ear can be much easier than reading the notation.

THE GAVOTTE:

The “Gavotte” is a very good example of this. If we were to learn a Gavotte – any Gavotte – by ear, we would think that it starts on the first beat of the bar because this is how Gavottes sound. But, curiously, one defining feature of the “Gavotte” is that it actually is notated as starting on the third beat. There must be at least one good reason for this, other than just to confuse the players, but it is very tempting to write out our Gavottes as they sound rather than as they are traditionally notated (see the Gavottes from the 5th and 6th Bach Cello Suites as well as from the E Major Violin Partita).

THE DELIBERATELY DISPLACED BARLINE AND THE IRRELEVANT BARLINE:

Brahms, more perhaps than any composer, loved to play with barlines, writing large sections of music for which the barlines seem to have absolutely no relation to the phrase structure and which, rather than helping with the reading, actually hinder it. In many large sections of the music of Verdi and Bach, the same phenomenon occurs, but whereas Brahms seems to delight in the deliberate creation of confusion (a very old-germanic type of humour), Verdi and Bach seem to just write their music as it flows out of them and don’t really worry at all about how the barlines correspond to the phrasing. The Preludes of Bach’s First and Second Cello Suites are full of music whose phrasing doesn’t seem to correspond with the barlines. Paganini’s Moto Perpetuo also gives us many good examples of this notation phenomenon which is why in the cellofun adaptation of this piece, two versions are offered: one with Paganini’s barlines and the other with barlines that correspond to the pulse of the phrases.

CHOICE OF BAR LENGTH (= PULSE FREQUENCY)

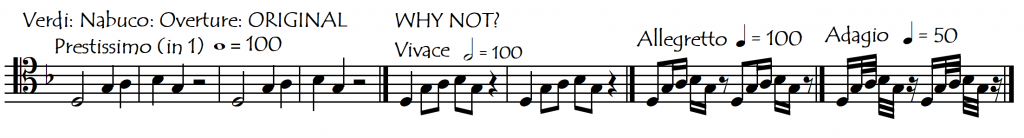

Even when the musical pulse does correspond to the time signature, composers have a large choice as to which time-signature they might use to notate their music. The exact same music, at exactly the same tempo, can be written with different rhythmic notations, for example, as an Adagio, a Moderato, or a Presto, simply by using the appropriate time signature and rhythmic note values. The fact that there are so many ways of notating the same rhythm is one of the main causes of rhythm-reading problems, especially in the orchestral repertoire – and most especially in the operatic repertoire – in which the frequent tempo and time signature changes can take us by surprise. In the following example, Verdi chose the Prestissimo 4/4 time signature with one pulse per bar, but the music could sound identical with the other alternative time signatures also. With each example, the frequency with which we might want to stomp on the beat is reduced. Basically, each barline is a new “stomp”, so by the time we get to the Adagio version, the party is over. Now the music, although still going at the same speed as in the first original Prestissimo version, is now floating ethereally. This is the meaning of the barline. According to Einstein, his “Theory of Relativity” was completely inspired by music, which is not at all surprising.

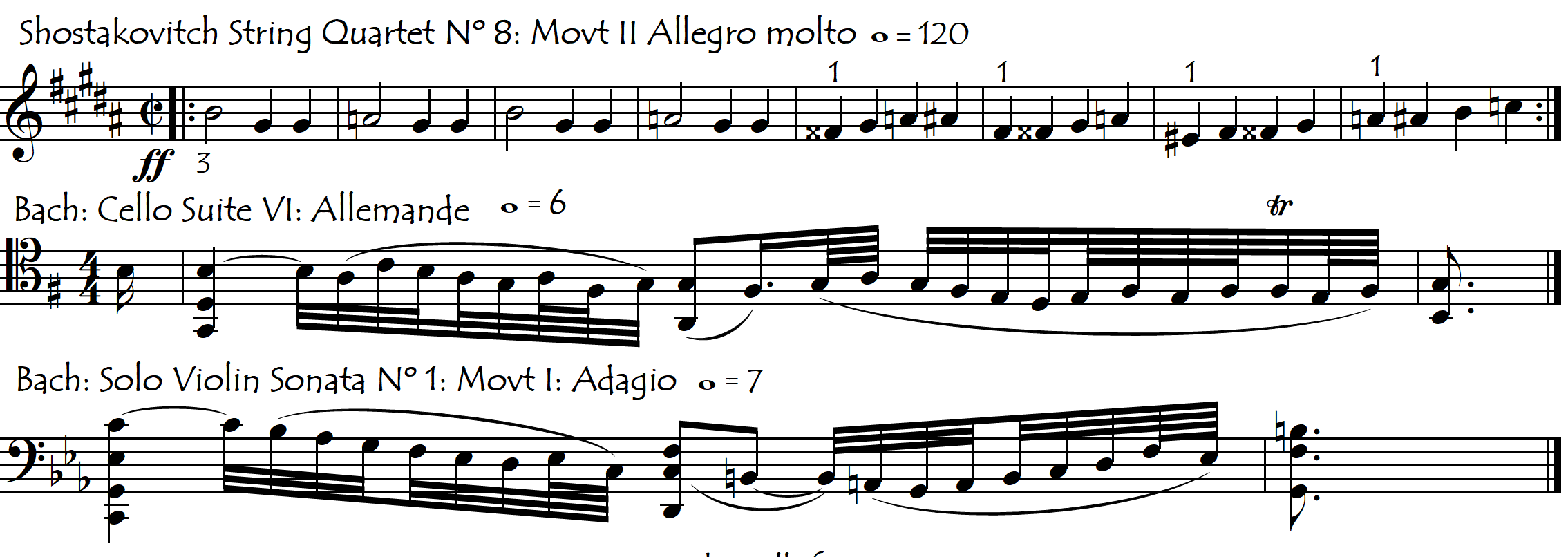

Verdi’s original choice is a very fast, exciting pulse, but even faster, and perhaps the world record in that department, would be the second movement of Shostakovich’s Eighth Quartet, in which the speed is “whole note = 120” or, in other words, two bars of 4/4 time per second. This reflects perfectly the absolutely maniacal frenzy (panic) that this movement represents, and is the absolute opposite of the deep religious calm of the Allemande from Bach’s Sixth Cello Suite and the Adagio from his First Unaccompanied Violin Sonata, in which one bar lasts an eternal 9-10 seconds!

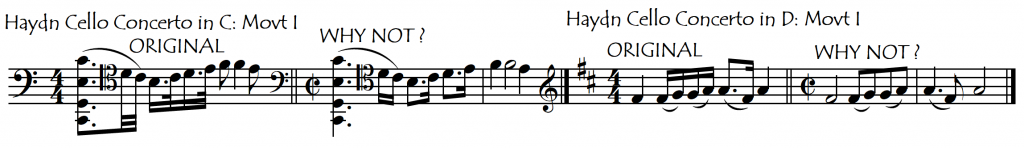

The cello repertoire has some other unexpected curiosities in the key-signature notation department:

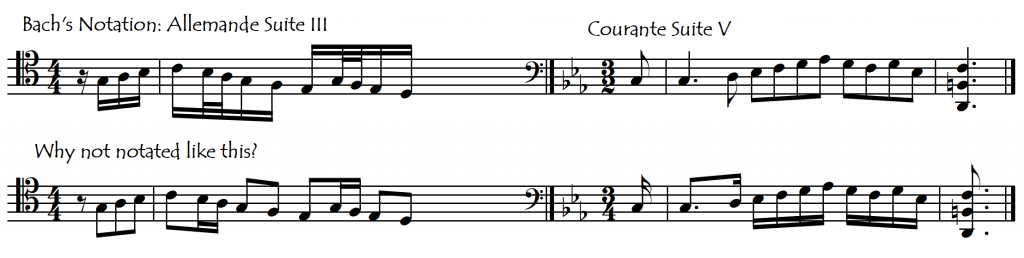

In some other movements of the Bach Cello Suites, Bach also writes the music using quite bizarre time signatures (note lengths). For example, just like in the Sixth Suite Allemande, in the Allemande of the Third Suite the note values are also half of what we might expect. In other movements, Bach does exactly the opposite, using the “old” style rhythmic notation of the pre-Baroque composers, in which the notes are written out with double their “normal” values. The Courante of the Fifth Suite (and the Sarabande of the Sixth Suite) are examples of this.

The use of time signatures requiring very small note values (half the length we might “normally” expect) is found also in several movements of Bach’s unaccompanied violin music, notably the Allemande from his B Minor Partita, the Grave that starts the A Minor Sonata, and the Adagio that starts the G Minor Sonata. This gives an abundance of tiny note values, which have been counted and compared in the table below:

|

USE OF VERY SMALL RHYTHMIC VALUES IN BACH SLOW MOVEMENTS FOR SOLO CELLO OR VIOLIN |

|||

|

PIECE |

SEMIDEMIQUAVERS |

HEMIDEMISEMIQUAVERS |

SEMIHEMIDEMISEMIQUAVERS |

|

Allemande: |

363 |

56 |

0 |

|

Allemande: |

107 |

35 |

0 |

|

Adagio: Vln |

157 |

97 |

4 |

|

Grave: Vln |

280 |

55 |

0 |

This stuff is hard to read ! Bach loved mathematics and reading this is mathematically challenging for the normal musician. To decipher this music we don’t even need our instrument: this is a mathematical exercise for which we just sit down with the music and a pencil and try to figure out the rhythms. This level of written rhythmic complication is however perhaps unnecessary. Its only real use is to make it clear that the essential pulse of the music is very slow. Rewriting these movements with note values twice as long (and bars twice as short) removes completely this unnecessary reading difficulty but we need to be careful when playing these pieces to make sure that we still feel them with a very slow pulse (minim instead of crotchet). That is why this music is available here in both the original version and the “easy to read” version (with longer note values).

2: BEAMING

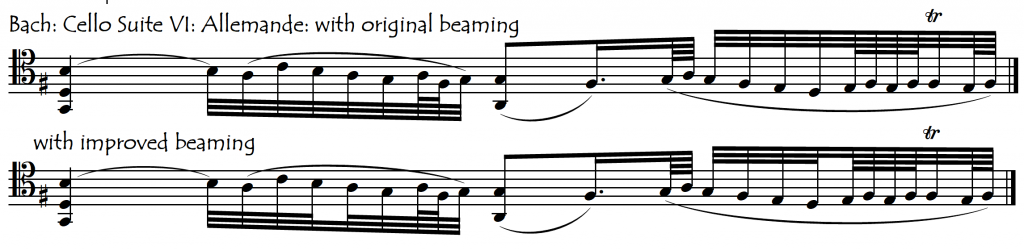

The thoughtful use of beam subdivisions can greatly help us make rapid sense out of passages in which many semiquavers (and/or smaller note values) are beamed together under one beat. When the sub-beams are broken at the corresponding beat subdivisions, this gives us an immediate graphic indication of how the notes are distributed across the beat. This situation arises most commonly in slow music, with rapid fioritura passages of many “tiny notes” under a slow pulse, as in some of the pieces discussed above.

Unfortunately, once a musical score (part) is printed, it would be painstakingly laborious to modify the sub-beams. In all the music published on this website, care has been taken to use “user-friendly sub-beaming” in these types of passages, to make the reading of the rhythmic subdivisions easier.

3: ORNAMENTATION AND GRACE NOTES: DOUBTS, CONFUSION AND AMBIGUITIES

Ornaments tend to be notated with signs (mordents, turns, trills etc) rather than with exact, precise rhythmic note values. These “shorthand” notational customs give the performer a certain interpretative freedom (and make the score visually less complex) but can cause doubt and confusion in players of every level of both skill and experience. Grace notes are always notated before the beat but are sometimes played on the beat. Where exactly do we place the grace notes or the notes of a turn and when exactly (and on which note) do we start our trill ?

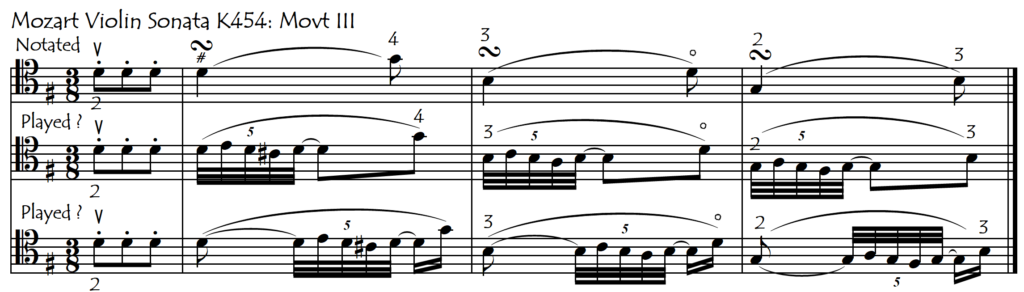

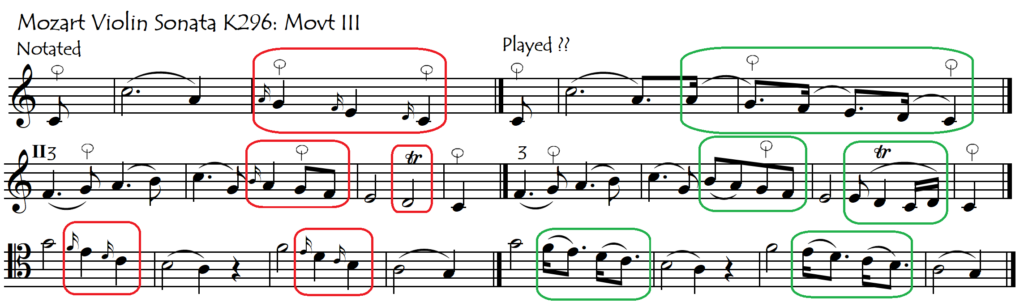

Sometimes, in the same phrase, some of the grace notes are played on the beat and others are played before the beat:

We are taught certain historical rules about trills and grace notes (in Pre-Romantic music, start trills from the upper note and play grace notes on the beat and for half the value of the main note etc) but these rules do not always apply. Ambiguities abound, but although this can create confusion it is perhaps not a bad thing because it gives us the freedom to be different and to find our own way !

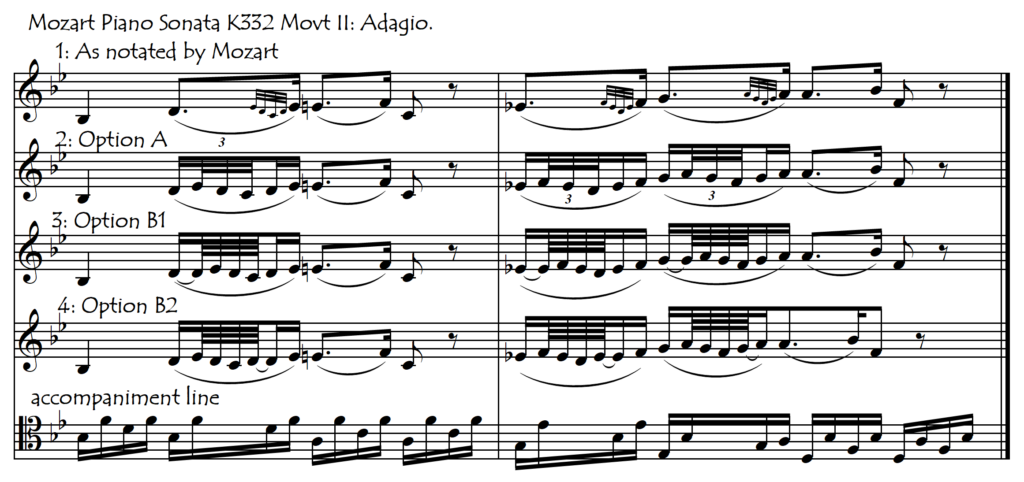

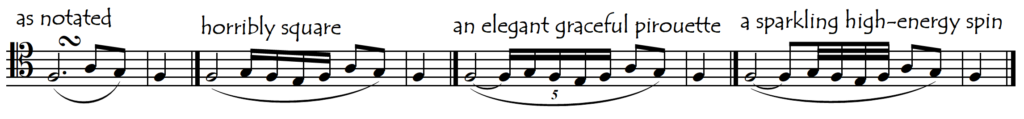

Turns often give us many different possibilities as to how we might play them with respect to the rhythmic placement of the notes. One useful idea to keep in mind concerning turns is that of the quintuplet, the use of which will often be the secret that makes our slower turns sound improvised and expressive rather than mathematical and mechanical:

Here are some examples of ambiguous turns from that master of ornamentation, Mozart: