Cello Fingering

For all string players, choosing fingerings, just like choosing bowings, is a very important part of both our interpretative and technical mastery. But choosing fingerings for the cello is considerably more difficult than it is for the violin and viola because:

- we don’t have as many notes under our hand and are unable (except for in thumbposition or with the open strings) to play a scale across the strings without shifting or doing a double-extension (see Cello/Hand Size)

- fifths are much harder to play on the cello than on our smaller cousins

Just like for bowings, choosing fingerings is a four-dimensional juggling act, a complex chess game, in which we are constantly assessing and balancing the relative importance of many different expressive and technical criteria. A “bad” fingering can make a passage almost inevitably ugly, while a “good” fingering for that same passage can make that same music suddenly sound a whole lot better. Knowing how to choose those “good” fingerings is one of the great differences between an experienced and an inexperienced cellist.

One of the most difficult aspects of choosing fingerings is that some fingerings will make a passage technically safe (easy) but musically ugly, while other fingerings will do the opposite (make it musically beautiful but technically dangerous). This choice between “beautiful but dangerous” and “easy but ugly” occurs most often when we need to decide whether to finger a passage across the strings (often easier, but not as beautiful) or on the same string (beautiful but more dangerous). This is one of the reasons why it is often not easy to say definitively whether any particular fingering is “good” or “bad”, and this is why we refer to fingering choices as a “juggling act”.

Let’s look now at some of the criteria for fingering choices. We can divide these criteria into two main categories (click on the links for more discussion and musical material):

1: EXPRESSIVE FINGERINGS:

On this dedicated page, we will look at fingerings that are chosen especially to make a passage more expressive, through the use of vocal position changes (with glissando), choice of string for colour sensitivity, choice of most favourable finger for vibrato etc.

2: TECHNICAL FINGERINGS:

And here we will look at fingerings chosen especially according to criteria of intonation security, hand and cello size, ease of playing, finger fluency (especially in fast passages), ease for the brain, size and acoustics of performance venue etc.

***************************************************************************************************************

Normally, the slower and easier the music is, the more our fingering choices can be based on expressive choices. Essentially this means shifting more, for two main reasons:

- in order to stay on the same string and thus maintain the lyrical vocal quality

- in order to avoid extensions

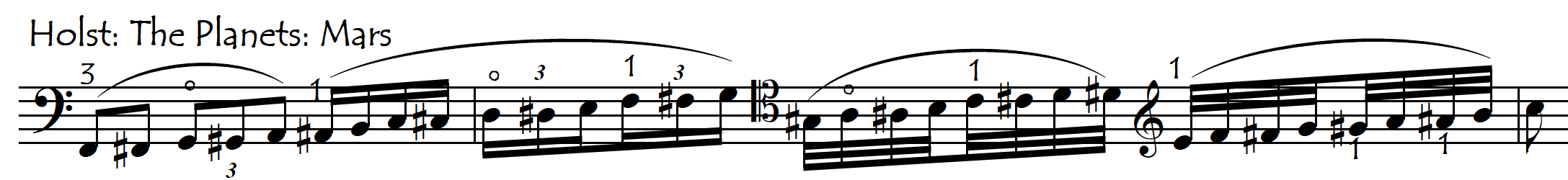

As the music gets faster it usually becomes more technically difficult and less “expressive”. This means that it also becomes less and less important to stay on the same string or to avoid extensions. In faster music, our fingering choices will need to be based more on technical criteria, to ensure simply that we can actually play the passage correctly. A good technical fingering can make the difference between easy and impossible, while a good expressive fingering can make the difference between boredom and magic.

****************************************************************************************************************

FINGERING PROBLEMS

Here below we will look at some of the most typical problems/issues that we might encounter in relation to the subject of cello fingerings:

HAND SIZE AS A FACTOR IN CHOOSING FINGERINGS

We mentioned before that it can be difficult to say whether a particular fingering is “good” or “bad” because this can depend very much on the characteristics and skill of the cellist who is playing the fingering. One of the most important characteristics that we cellists need to take into account when choosing fingerings is our hand size.

Whereas our choice of bowings is largely determined by musical factors and shows a lot about our intelligence (both musical and general), our choice of fingerings is usually much more influenced by our hand size. This is because it is our hand size that will determine to a large degree just how much hand tension and discomfort will be caused by our extensions, and a lot of the criteria for choosing good “technical” fingerings are based on how to reduce tension and strain in the hand.

While we all play with bows of similar size and weight, hand sizes can be wildly different between one cellist and another. Therefore, an absurdly bad bowing is normally bad for anybody and everybody, whereas what would be an impossible fingering for a petite small-handed Japanese cellist might be a great fingering for a giant bear-handed Scandinavian. This is the main reason why there are such a large variety of fingerings out there. It is truly astonishing (as well as instructive and revealing) to see the same passage played with a large number of totally different fingerings by different cellists. In an orchestral cello section sometimes there are as many different fingerings for a difficult passage as there are cellists in the group!

The subject of hand size and cello fingerings will reappear often on this page.

FINGERINGS AND EVOLUTION:

Hand size has probably not changed significantly over the last 300 years and neither has the cello’s size or shape changed much since finding its “modern” form 300 years ago, but cello fingerings have evolved tremendously. Fortunately, we can see the (dreadful) fingerings that were used centuries ago, thanks to published material by pedagogues and cellist/composers such as Berteau (1691-1771), Cupis (1732-1808), Duport (1749-1819), Romberg (1767-1841), Dotzauer (1783-1860), Lee (1805-1887), Grutzmacher (1832-1903), Stutchewsky (1891-1982) etc. Using many of these fingerings nowadays is truly a trip backwards in time, a historical exercise equivalent to travelling by horse and carriage or in a Model T Ford.

UNHELPFUL FINGERINGS IN CELLO EDITIONS

Unfortunately, music publishing has not kept up with the times, and these stone-age fingerings are still present in many editions that are used and sold today. It is as though a student of medicine were to find in their medical textbook, instructions as to how to cure illnesses by the application of bloodsucking leeches ! As a curiosity, I counted the number of sub-optimal fingerings found in a randomly chosen study (Nº 18) by Duport, fingered by Grutzmacher more than 100 years ago in an edition that is still sold today by very well-known, reputed, music publishers. Approximately 30% of the notes needed to be refingered. Fortunately, editions of the Popper and Duport Studies are available, since 2005, from Barenreiter with totally intelligent, modern fingerings (and bowings) by Martin Rommel.

But sometimes, even editions fingered by much more recent cellists, are not free of unhelpful fingerings, mainly because of the issue of hand size. To be invited to edit a cello edition (with fingerings and bowings), it helps to be a famous, magnificent cellist. To be a magnificent cellist it helps to have a large hand. The result of this logic is that most cello playing-editions have fingering suggestions designed for a large hand. Sometimes, these fingerings are often not just unsuitable but actually unplayable for small-handed cellists.

Leonard Rose was a wonderful cellist, musician, teacher and person……. and he edited a lot of cello music. He felt that he was blessed with hands that lent themselves to the cello and he wrote, “I have a tremendous lack of webbing in my hands. I am capable of doing many extensions on the instrument so that I can cover a vast area quite quickly”. The fingerings that he put into his editions are excellent for a large flexible hand like his, but are often eminently unsuitable for a smaller-handed cellist.

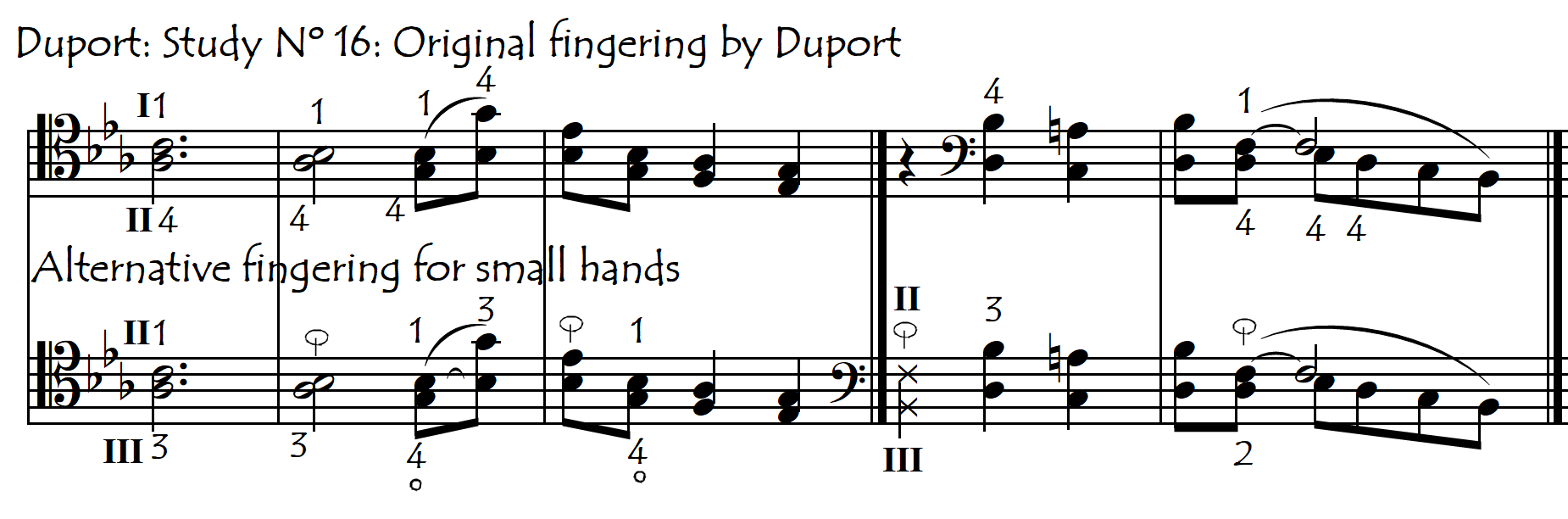

Like Leonard Rose, Friedrich Grutzmacher (1832-1903) and Joachim Stutchewsky (1891-1982) both edited an enormous amount of music and pedagogical material for cello, a lot of which which is still used today. But both of them obviously had gigantic hands and, for the small-handed cellist at least, their fingering suggestions are often a sure path to self-destruction. Even Jean Luis Duport (1714-1789), Napoleon’s favourite cellist, the cellist with whom Beethoven premiered his Opus 5 Sonatas, and the most famous pedagogue of his time, indicates fingerings that for the small cellist are unplayable:

The significance of hand size is only one of the reasons why fingerings in music editions can be so dangerously unhelpful – especially for small-handed cellists. Even some of the best and most well-known editions of music have, with disturbing frequency, some extraordinarily “bad” fingerings printed into their cello parts. The older the edition the more likely we are to find this situation, but it happens also in some good modern editions. After having produced a rigorous, scholarly, musicologically impeccable edition, many music publishers then put their trust blindly in a well-known cellist, who proceeds to stamp his personal, idiosyncratic, eccentric mark all over their carefully authenticated edition. A good example of this is the first Henle Urtext edition of the Beethoven cello sonatas, with a lot of ridiculous and (sometimes) impossible fingerings by André Navarra, that even he himself did not use.

Cellists who trustingly follow the edited fingerings, believing that they are the helpful hints of an expert, will often find themselves severely misled. They may even never realise why it is that they are sounding so bad in spite of doing exactly as advised by the edition. A compilation of passages with awful, unhelpful printed fingerings could occupy many pages and would be quite a comical collection ……. if it weren’t so tragic for those trusting small-handed cellists who actually try to use them.

Whiting-out (Tippex) the published fingerings is a laborious solution but has the advantage of leaving the score clean so we can then at least write and see our own fingerings. To avoid this necessity, all the sheet music downloadable from this website is available in both edited (with fingering and bowing suggestions) and “clean” (with no fingering or bowing suggestions) versions.

The fingerings suggested in the “edited” versions of music found on this website are always conceived for small-handed cellists. This is because large-handed cellists don’t really need fingering suggestions. Why bother to try and help a fish to swim? In order to avoid harmful excessive left-hand tension, a small hand needs a different fingering system, with more shifting and fewer extensions. As it has taken this writer (a very small-handed cellist) almost a lifetime of cello playing to realise this, the fingering suggestions in the music published on this site are designed to save other small cellists from that same suffering.

“STANDARD” FINGERINGS FOR SCALES:

Most cello methods, especially the older ones, teach “standard fingerings” for the different scales, and there is often only one fingering for each scale. These standard fingerings may be useful as gymnastic training and warm-up exercises, but are often however not the best fingerings in a musical situation. In “music”, unlike in standard scale exercises, scales rarely start and finish on the tonic, and the rhythmic variety of the scalic sequences is almost infinite. Each specific musical situation will have its own appropriate optimum fingering solutions which very often will not be those proposed by the “standard” fingerings. This situation applies much more to scales than to arpeggios. It would appear that the first teacher of the marvellous cellist Santiago Cañon gave him a personalized scale workbook in which even the C major scale came with a huge number of different fingerings (17?), including many using the thumb in the lower regions. Santiago is deservedly famous, but his teacher should also be equally famous!

The need for many different scale fingerings can be most easily seen in chromatic scales because these have such a huge variety of possible fingerings:

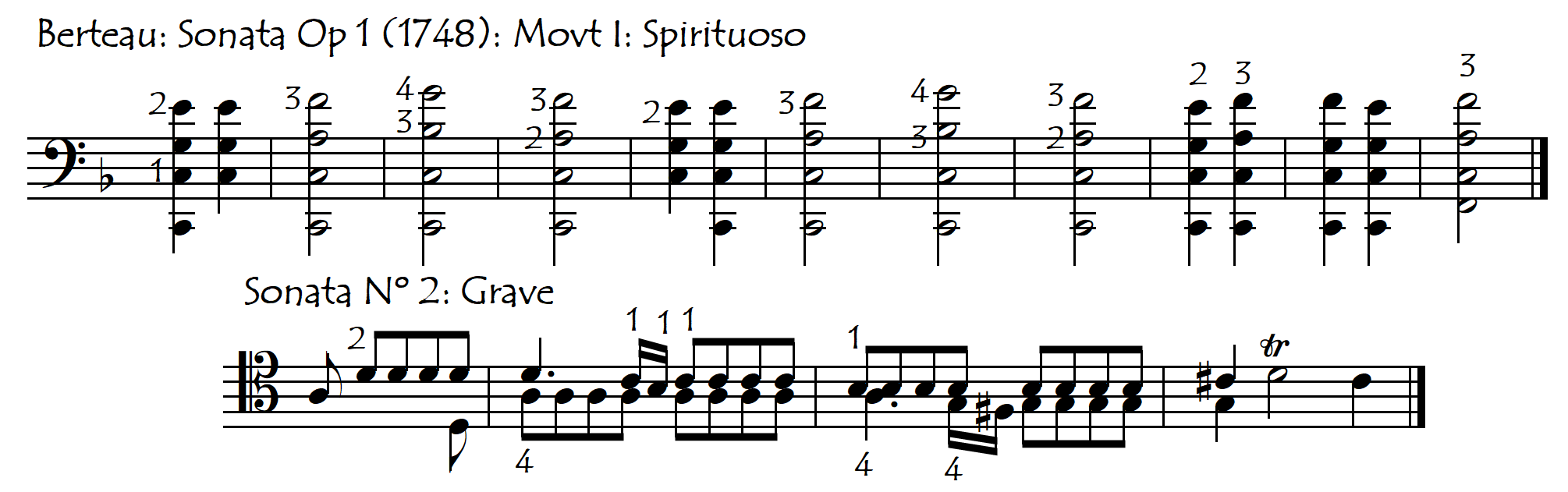

BAROQUE FINGERINGS: THE CELLO AS A LARGE VIOLIN

Several passages in Bach’s Cello Suites seem to suggest that, in the Baroque period, the cello was fingered as though it were a large violin (see Violin Fingerings in the Bach Cello Suites). This idea is supported by the following examples, showing the original fingerings of the cellist composer Martin Berteau (1691-1771) as published in the first edition of his cello sonatas Op 1 in 1748:

Nowadays, we tend to use the thumb in the Neck Region rather than using violin fingerings (see Use Of Thumb In the Bach Suites), but in the mid-18th century this was not the case. Thumbposition had only just been discovered then and was, for a very long time, apparently used only as a way to open up the higher regions of the fingerboard (see History Of Thumbposition)

CONCLUSION

Very often our playing will sound much better when we do neither the printed fingerings nor the rigid “standard fingerings”. Choosing our fingerings thoughtfully according to both the music’s peculiarities (especially the rhythmic factors), our hand size, and sometimes even according to the individual instrument’s response, is not only more creative but also will probably sound better. This is especially so for cellists with small hands.