Shifting and Extensions On The Cello

This is a sub-page of the Extension article.

Comfortable, secure shifting (and playing in general) is greatly helped by having a totally relaxed left hand. When shifting to an extended position this relaxation is more difficult to achieve because of the hand strain created by the extension which follows the shift.

Here, we so much want to sing and vibrate beautifully, but the fact that we need to stretch out for the note after the shift means that our hand cannot be as compact and relaxed as we would like it to be. This hand strain, caused by the extension after the shift, not only can make our vibrato tighten but also can cause intonation insecurity for the shift.

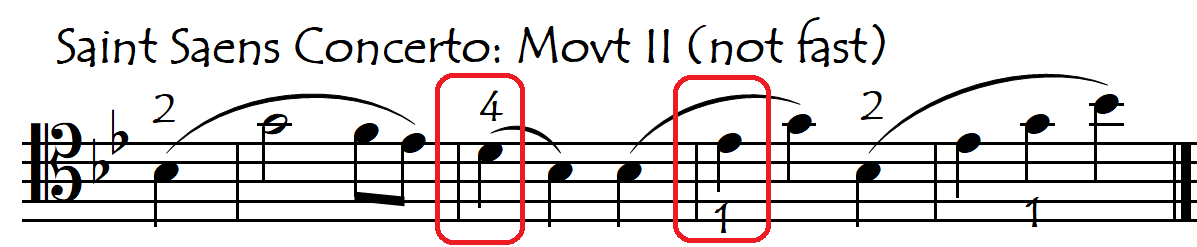

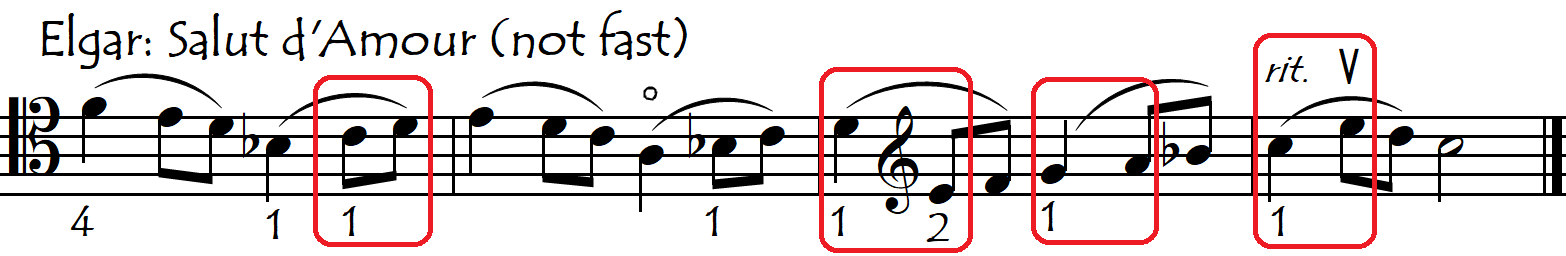

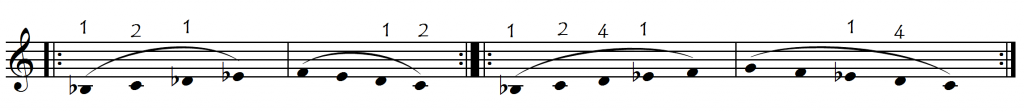

In faster passages it is uniquely this intonation security that can disturb us because we don’t need to do vibrato on those faster notes. Small-handed cellists may choose to shift to the close-position hand posture (1-3 tone) rather than the extended 1-2 tone (see “Fingerings To Avoid Extensions“):

The very hardest shifts involving extensions are those that go from one extended position to another extended position, so let’s look first at these.

THE HARDEST SHIFTS: SHIFTING IN EXTENDED POSITION

Shifts in which we are obliged to maintain our extended position are the most uncomfortable shifts. This is because the added extension-strain is present both before and after the shift (and most probably during it as well). However – and fortunately – just because a shift occurs between two extended positions doesn’t mean that we must automatically do the shift “in extended position”. Normally we will take every opportunity to relax the hand into a non-extended position before (or during) the shift so that we can do our shifts in the non-extended position. Then we will re-extend on arrival at the new position. This relaxation of the extended position into a non-extended position for the shift is automatic in Scale/Arpeggio-type shifts because they use the contraction of the hand as part of their fundamental process of shifting:

In the case of Same-Finger and Assisted shifts our ability to relax the hand for the shift will depend on the speed of the music and the size of the shift. The smaller the shift and the faster the music, the more we will be obliged to maintain the extension during the shift. Here below this is illustrated for same-finger shifts:

And the following examples illustrate the same principle for Assisted shifts:

In the case of double stops also, just like in the faster extended passages, this relaxation may not be possible, as in the following examples. These arpeggio patterns can be transposed all over the cello.

In these cases, in which we are obliged to maintain our extended position during the shifts, we are dealing with the most uncomfortable shifts. This is because the added extension-strain is present both before and after the shift (and most probably during it as well). Small-handed cellists may want to avoid these “shifts-in-extension” by refingering them in such a way as to eliminate the extensions (see Fingerings to Avoid Extensions). The following example has the exact same notes as the example above, but now the extensions have been entirely removed by substituting the thumb/second finger major third for the traditional first/fourth finger major third.

Even without using the thumb, there are many ways to refinger note sequences in such a way as to avoid shifts in extended position. The following four examples show how we can reduce the shifting-in-extension load by different degrees through different options of refingering. These examples can be transposed all around the fingerboard:

THE WORST SHIFT IN EXTENSION: DOWNWARDS ONTO THE FIRST FINGER

The extended-back first finger in the “doublebass posture” is fundamentally unstable. The first finger is not only sticking out far away from the centre of gravity and balance of the hand, it is also tense and strained. Shifting on or to a finger in these conditions is very unergonomic. While shifting upwards on this extended finger is not wonderful, it is nevertheless much more comfortable than shifting downwards on it. The backwards shift seems to amplify its instability. It is as though we were pushing it in totally the wrong direction. For this reason, small-handed cellists may want to finger passages in such a way as to avoid shifting backwards on this extended finger.

Upwards scales across the strings in which a semitone interval coincides with the change of string require a shift back to the extended first finger. If we can plan our fingerings carefully in advance, we will often be able to avoid fingering our scale in such an unergonomic way, especially if they are legato, but equally often we will have to do these uncomfortable fingerings, especially when sight-reading.

SHIFTING BETWEEN EXTENDED AND NON-EXTENDED POSITIONS

Shifting in extension is extremely awkward. But even shifts for which only one side of the shift is extended can still be problematic. This is because, apart from the strain of the extension, the change from normal to extended hand posture can constitute a source of instability. When this posture change occurs during a shift, this can add considerable insecurity to the shift. In slower music we may have time to adjust our different hand posture either before the shift, after arriving at the new note, or even during the shift, so we can effectively do our shift in the safe, comfortable, non-extended position. In rapid shifting passages however, we don’t have this time. Karl Popper and Paul Tortelier had two opposite solutions to avoid the destabilising influences of these changes of hand-posture during shifts. Popper solved this problem by having his left hand as much as possible in the “Violin Posture” in all regions of the cello fingerboard, whereas Tortelier solved it by being as much as possible in the “Bass Posture” (see Hand Postures in Extension).

Popper’s solution is the most commonly adopted one. The fact that in the Intermediate and Thumb Regions we normally use the Violin Position means that, in faster shifting passages between the Neck Region and these Higher Regions, it is helpful, whenever possible, to use the Violin Position also in the Neck Region. This only requires the use of intelligent fingerings to avoid large extensions (and therefore to avoid the use of “Bass Posture”) in the Neck Region before (or after) rapid or difficult shifts between the regions. (examples)

Shifts between extended and non-extended positions can be divided into two groups: the “easy” ones and the “hard” ones.

1: THE EASY ONES: SHIFTING FROM EXTENDED TO NON-EXTENDED POSITION

When we shift from an extended position into a non-extended one, these are “easy” because we can relax the hand before (or during) the shift, into its non-extended position. We have absolutely no reason to maintain the extension any longer than necessary, in fact we have every reason to relax the extension back into non-extended position at the very earliest opportunity, so that the shift can be made in the relaxed non-extended position. In the examples below, the arrows indicate where we should relax the hand into the non-extended position.

2: THE HARDER ONES: SHIFTING TO EXTENDED POSITION FROM NON-EXTENDED POSITION

In these shifts, we are shifting from a relaxed into a strained position. We have three possibilities for deciding when we will change our hand posture into the extended position: before, during or after the shift. The “x” notes are intermediate notes that are not actually sounded.

PRACTICE MATERIAL

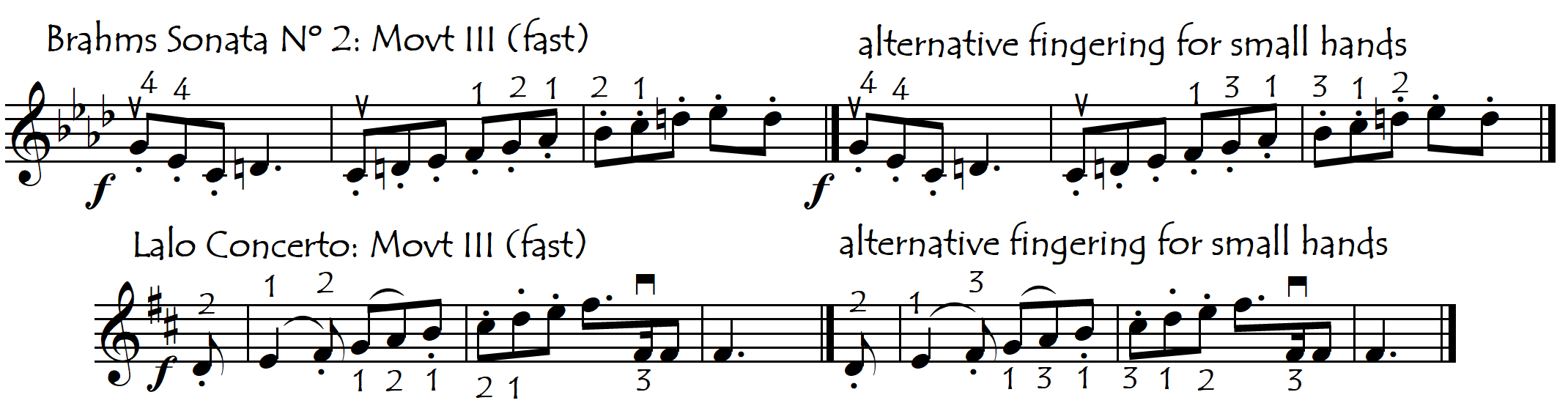

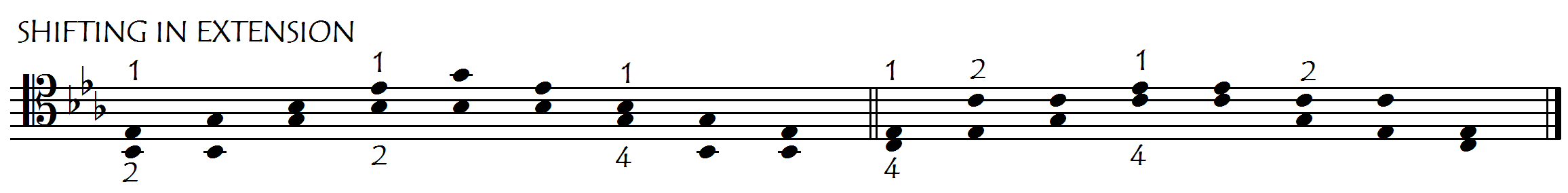

Unfortunately, fingerings for avoiding shifts in extension are not always possible or practical. We have no choice but to work on this awkward but essential skill. At the most basic level this involves working simply on our extended position to create basic hand strength and flexibility. Only then do we add the extra complication of shifting, for which probably some of the best and simplest material is scales in thirds. We don’t even need any written music to practice these. The following example is in C-major, but we can play them in any key.

Click on the following links for more detailed material for working on these shifts-involving-extensions across all the fingerboard regions.

Shifts Involving Extended First Finger: All Regions: SINGLE-NOTE EXERCISES (no doublestops)

Shifts To Extended First Finger: REPERTOIRE EXAMPLES

Shifts To Extended 2nd, 3rd and 4th Fingers: EXERCISES

Stepwise Scale/Arpeggio-type Shifts Down Into Extended Position: EXERCISES

Stepwise Scale/Arpeggio-type Shifts Down Into Extended Position: REPERTOIRE EXAMPLES