Shifting to Another String

Shifting on the same string is somewhat different from shifting to a different string. The concepts of “Same-Finger Shifts“, “Assisted Shifts” and “Scale/Arpeggio-Type Shifts” that are discussed in “Finger Choreography” are mainly applicable to shifts on the same string, because when we shift to a different string we can normally put the” new” finger down on the “new” string before the shift starts. This means that most shifts to a different string can be – and normally are – felt and measured simply as same-finger shifts, even when the finger previous to the shift is not the same as the target finger. This advantage of being able to place the new finger before the shift is why shifting to another string is often easier than shifting on the same string.

Shifting to a new string does however introduce some new complications that we don’t have when shifting on the same string:

- we need to decide on which string (“old” or “destination”) we will “do” the shift (glissando)

- we need to decide when to place the new finger on the new string

- we need to do a slightly more complicated mathematical calculation relating the shift distance to the interval size because the change of string distorts this relation

- for shifts with the same origin and target finger, we somehow have to get our finger across from the original string to the new string during the shift.

Let’s look now in more detail at these special characteristics of shifts to a new string:

SHIFT ON OLD OR NEW STRING?

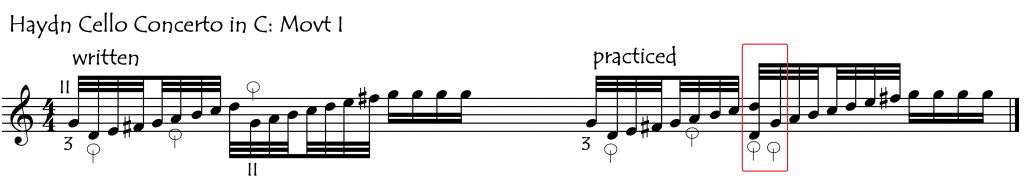

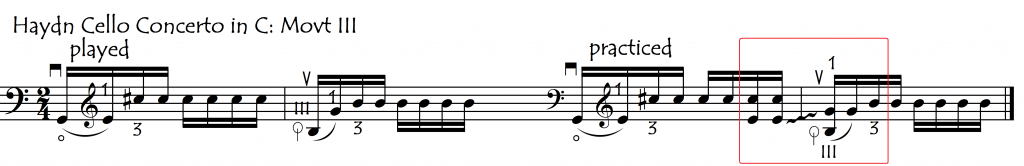

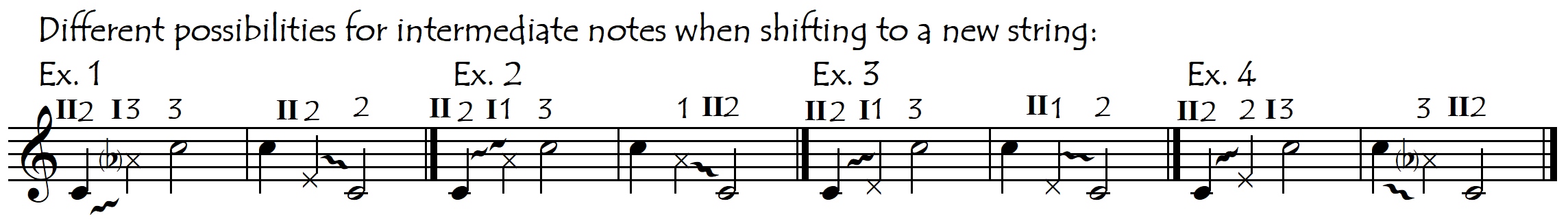

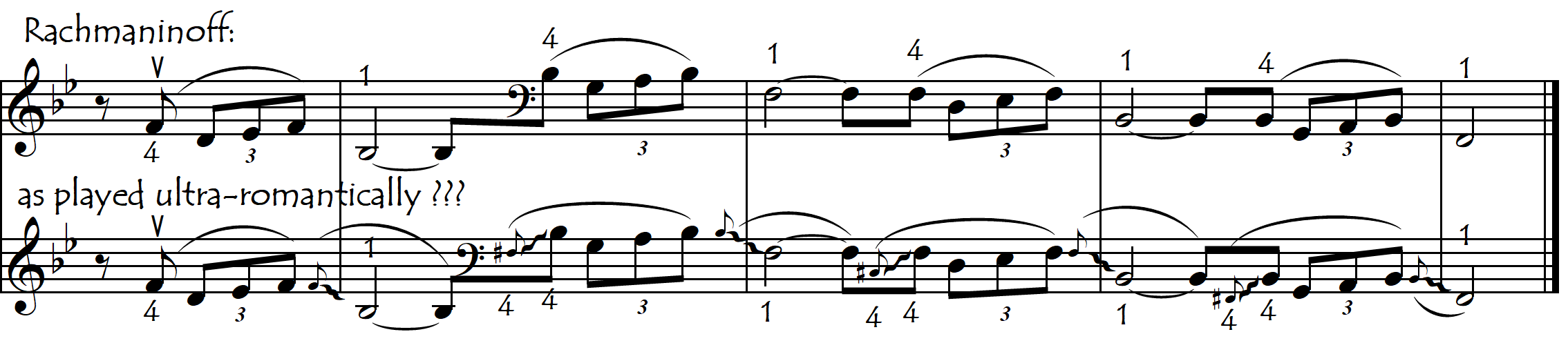

In the first of the above examples, no matter what fingers we place on our origin and target notes, in order to achieve the smooth legato we will always do the shift as a “same-finger-shift-on-the-new-string”. In the second example, however, we have a lot more choices as to how we might do the shift. Now, because our shift (glissando) is silent, we can choose to do the shifts on either the new string (on the new finger) or on the old string (on the old finger). We could even decide to do the shifts as “scale/arpeggio-type”. In other words, not only do we need to choose on which string we will make the shift, but also we now have a greater choice of finger choreography and of intermediate notes.

Example 1 uses “same finger shifts on the target string”, example 2 uses “scale/arpeggio-type shift to the target string”, example 3 uses “scale/arpeggio-type shifts on the lower string”, while example 4 uses “same-finger-shifts-on-the-old-string” (= assisted shift to new string!). Yes, this sounds quite complicated ……. but that is the way it is when shifting to a new string!!

WHEN TO PLACE THE NEW FINGER ON THE NEW STRING?

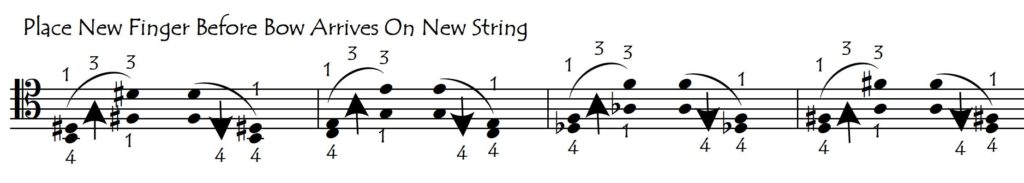

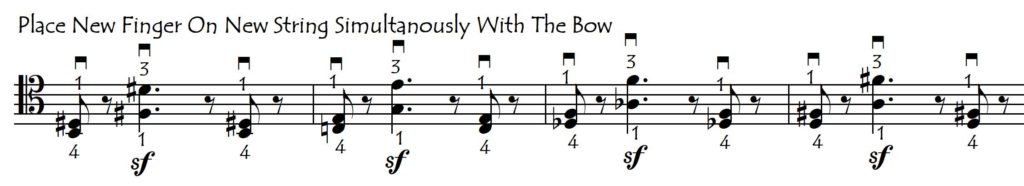

When moving to a new string (with or without a shift) we will normally place the new finger anticipatedly on the new string before we start to sound the string. This is usually a helpful thing to do because it eliminates the complications associated with exactly coordinating the sounding of the new string (arco or pizzicato) with the simultaneous placement of the finger. This anticipated placement of the finger is especially important in legato (slurred) string crossings. In the illustration below, the arrow indicates the placement of the new finger on the new string (before the bow gets there).

More rarely we might want to articulate the new finger simultaneously with the bow on the new string to give great rhythmic (and positional) decisiveness.

THE GLISSANDO IN SHIFTS TO A NEW STRING: DOUBLY IMPORTANT

As with shifts on the same string, we need to be able to “hear” (imagine) the shift interval in our heads even if we decide to make no actual audible glissando during the shift. Practising all shifts with an audible glissando, programs the brain and the hand so that even when we do the shift silently, we can still hear it in our imagination. This is especially important for shifts to a different string because here the physical shift distance no longer corresponds to the size of the musical interval.

SHIFTS UPWARDS TO LOWER STRING OR DOWNWARDS TO A HIGHER STRING:

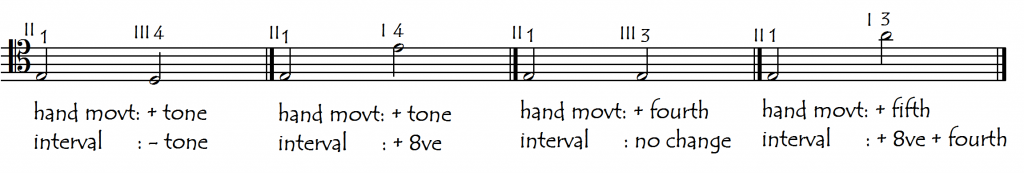

In a shift to a new string, not only does the glissando no longer correspond to the entire shift interval, but also, to complicate matters, the audible glissando to the new note can even sometimes be “outside of the shift range”. This occurs when we shift to a higher position on a lower string, as in the first and third bars of the above example, or when we shift to a lower position on a higher string. The following examples illustrate these two situations:

In other words, for shifting upwards to a lower string while the note progression normally goes downwards (or stays in unison), the glissando to the new note goes upwards. And for shifting backwards (downwards) to a higher string, while the note progression normally goes upwards (or stays in unison). the glissando to the new note goes downwards.

ADDING DOUBLE-STOPS AS A PRACTICE AID

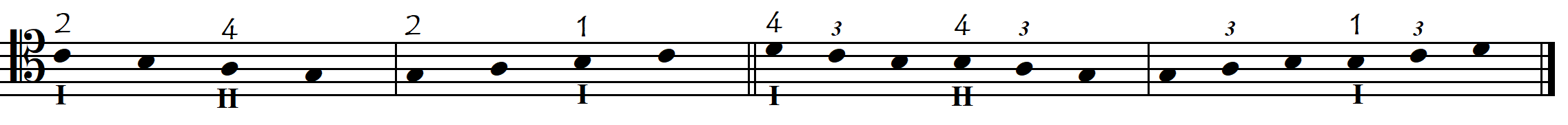

For practising shifts to a neighbouring string, adding a doublestop just before the shift is a great help, both to hear what is going on and to ensure that we do actually place the new finger before the shift. This means simply that, just before our shift, we will sound (normally with the bow) the “new” finger (and string) simultaneously with the “old” finger (and string). Perhaps this idea sounds complicated, but it actually isn’t ! An example will show this better than 1000 words:

Most commonly, for shifts to a new (different) string, we will shift on the new finger and on the new string, but not always. Sometimes we may have to shift on the “old finger and string” but the principle of the utility of adding a double stop before the shift remains the same:

SHIFTS TO A NEW STRING WITH THE SAME TARGET AND DESTINATION FINGERS

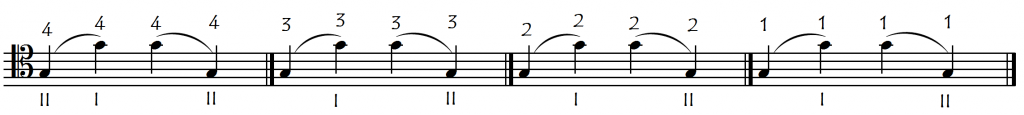

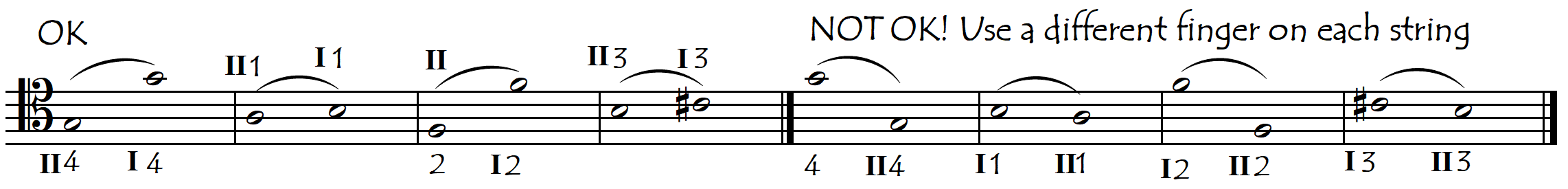

A “same-finger” shift on the same string is the easiest type of shift to do. But if the shift is to a different string, this situation is reversed. Same-finger shifts to a new string are the most problematic (compared to the other shift choreographys) because now we are unable to prepare the placement of the shift finger on the new string before the shift. To illustrate this, look at the following examples:

These shifts are basically like fifths with a shift in the middle, and we know that fifths complicate matters greatly on the cello. Here, we will need to get the finger over to the new string during the shift, because playing both the “origin” and “target” notes as capo-fifths (one finger stopping the two strings simultaneously like a guitarist’s “capo”) is rarely a good option from the point of view of vibrato, sound quality and intonation.

If we are shifting to the higher string, then moving the finger over to the new string during the shift is not particularly difficult. Problems arise when we need to shift to the lower string on the same finger, as occurs in the second part of each of the above bars. For anatomical reasons it is impossible to make this movement truly legato, so we simply do our best to avoid these types of fingerings (same-finger shifts across to a lower string) in legato (slurred) shifts.

We can summarise this difference in the following examples:

*****************************************************************

PRACTICE MATERIAL FOR SHIFTS TO A DIFFERENT STRING (WITH ALL FINGER CHOREOGRAPHYS)

Here are some links to practice material for working on the specific skill of shifting to a different string:

Assisted Shifts to New String: EXERCISES Assisted Shifts to New String: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

Scale/Arpeggio Shifts to New String: EXERCISES Scale/Arpeggio Shifts to New String: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

Same Finger Shifts to New String: EXERCISES Same Finger Shifts to New String: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS