The Glissando (Portamento) for Shifting Technique and Musicality

THE GLISSANDO (PORTAMENTO) AS AN EXPRESSIVE DEVICE

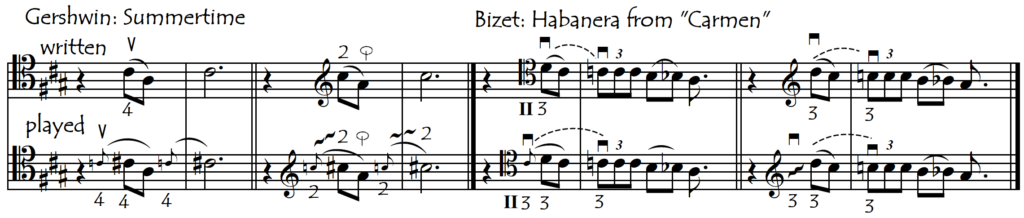

Sliding up (or occasionally down) into a note can be a magnificent expressive and dramatic device. It allows us string-players (as well as singers and trombonists) to connect our notes with a beautiful legato, no matter how far apart or close together the notes are. In gentler music, sliding into a note gives it a lyrical, vocal, expressive quality (beginning), whereas in more intense music it gives drama and intensity. Singers quite naturally use glissandos/portamentos all the time.

Glissandi are not used exclusively to make beautiful connections between notes. We can even sometimes use an (upwards) glissando to start a note after a silence. Especially in jazz and popular music styles, it is often much more beautiful, gentle, natural and “organic” to start a note by sliding up into it rather than with a clean, crisp, mechanical, metronomic, robotic start (such as heard in MIDI computer music). Singers – especially jazz singers – do this very often.

GLISSANDO, GLISSANDI, GLISSANDOS OR

PORTAMENTO. PORTAMENTI, PORTAMENTOS ?

The words “portamento” and “glissando” are interchangeable but we will prefer the word “glissando” because it better conveys the idea of the finger sliding along the string rather than being somehow carried. “Glissando” is the italian word for “sliding” (or “a slide”) whereas “portamento” comes from the italian verb “portare” which means “to carry”. When we apply this same concept of “connecting notes together” in our bowing, we get “portato“, in which the notes are also delicately joined, this time by the bow.

If we keep to the italian language for our musical terminology, then the plurals of both of these terms would end in an “I” (“glissandi/portamenti”) but if we don’t mind being less linguistically pure then we could just use “glissandOS/portamentOs” as the plural. Take your pick! Whichever of the six words we choose to use, this little technique is an absolutely fundamental component of both our expressivity and shifting tool-boxes. Let’s now explore this in greater detail:

GLISSANDO AS A TECHNICAL AID FOR SHIFTING

Glissandos not only sound beautiful but are also a beautiful technical aid for finding a new position. Sliding audibly into a note is the easiest way to find it safely and securely: just think about the way violinists tune their instrument, finding and tuning their perfect fifths by sliding up into them. An audible glissando is the most important facilitator of accurate shifting because it allows us to do two absolutely vital things:

- to accurately measure (aurally) the distance travelled by the hand

- to control the arrival at the target note with absolute intonation precision

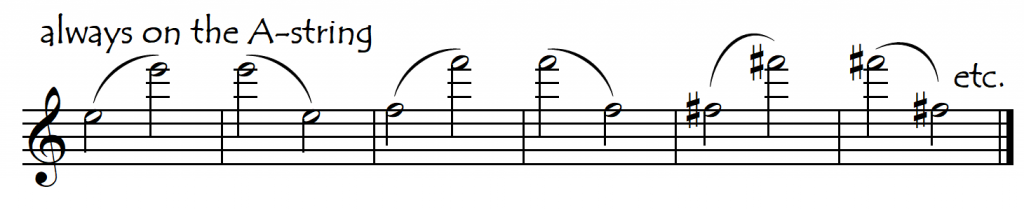

Even when we have absolutely no idea of the position of the target note, an audible glissando alone can give us sufficient spatial/aural feedback to be able to find our new note safely and accurately. This situation occurs especially in the high Thumb Region, where we have no physical spatial references to help with our positional sense. Play the following intervals firstly using same-finger shifts (because these give the smoothest glissando). Then try the shifts with other fingerings, but always with an audible glissando.

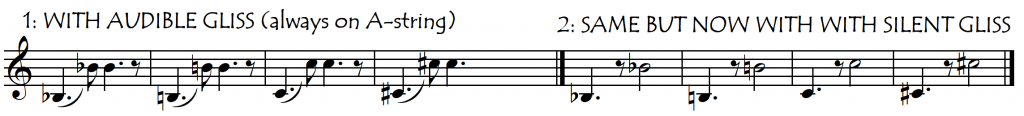

Even when a shift must be silent (without an audible glissando) for musical reasons, we can still practice it with an audible glissando. We do this in order to program our brain (and hand) with the aural memory of the interval. If we practice the shift with an audible glissando enough times, then when we finally do the shift with the “silent” glissando, we will still hear it in our inner ear and our hand will go to the correct place, as though we were actually hearing the glissando.

GLISSANDI UP TO NATURAL HARMONICS: THE FIRST STEP

Perhaps the easiest way to start learning the principles of how to do (control) glissandi is to practice sliding up to natural harmonics. The arrival note is automatically in-tune and sounds very easily, which means that we can do these shifts without tension. In this way, we can get used to doing our shifts with relaxed, easy, smooth glissandi, which is ultimately one of the most essential skills of good string playing. We can start with smaller shifts to the midstring harmonic (on different strings), and then progressively shift from further away. The next step is to choose increasingly higher (natural) harmonics as our destination note. This also helps us to familiarise ourselves with the higher regions of the fingerboard (Thumb Region). There is no need to write out these exercises: just improvise !

GLISSANDI TO AN “INTERMEDIATE NOTE”: GERMAN SHIFTS OR FRENCH SHIFTS?

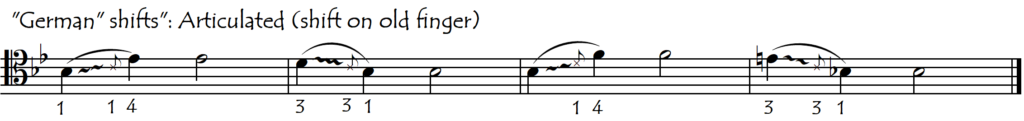

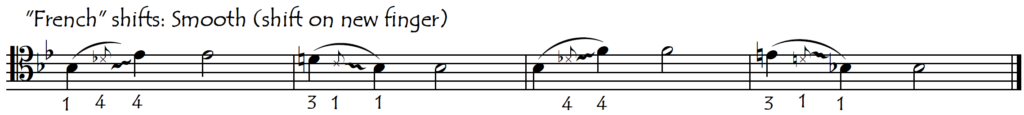

The simplest glissandi occur in same-finger shifts, where, by definition, our target note is played with the same finger as our departure note. But glissandi don’t always have to be necessarily on the finger of our target (destination) note. Some assisted shifts want to have the target note articulated cleanly, and in these cases, our glissando, rather than being on the target-note finger, will be on the finger of the note that precedes the shift. In these shifts, rather than sliding into our target note, that target note is sounded cleanly, with an articulation. In the case of upwards shifts, once the lower finger has slid into its new position, we simply articulate the (higher) destination finger. In the case of downwards shifts, the target note is sounded by the removal of the higher finger. This is why we can call these shifts “articulated shifts”. In both upwards and downwards shifts the note that we shift to is like a “stepping stone”. We can call these “stepping stone” notes “intermediate notes”.

This type of shift is less romantic, less sensuous, less seductive than those shifts in which we slide into the new note on the new finger. Perhaps this is why the technique of the articulated shift has sometimes been called “the German shift” while the slide on the new finger is called “the French shift”. In the “German shift” the shift distance is measured mathematically on the old finger, like a computer, while in the “French shift” the distance is measured aurally, like a singer.

SLIDING UP DISCREETLY TO A “STARTING NOTE”

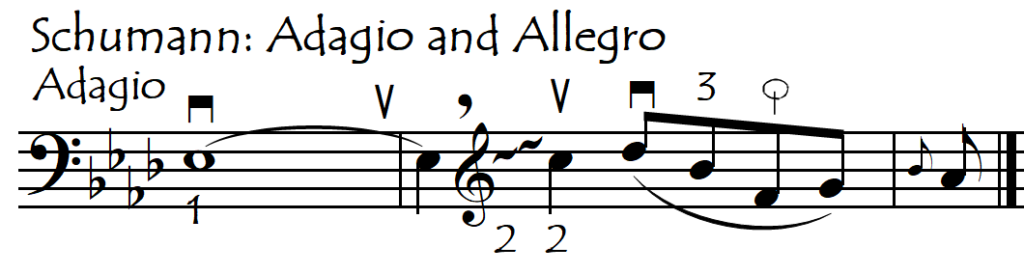

Glissandi are not only useful in shifts. As mentioned above, even when we have to find a note after a silence, it can be very helpful for our intonation security to do a discreet slide up into it, especially when our other little tricks for finding notes after silences such as left-hand percussive articulation for example (see Positional Sense) would be musically disruptive. This technique for finding a new note is most suited to imperceptible, vocal-like note-beginnings in the upper half of the bow because this allows us to make our little glissando so softly that it can, if necessary, be completely inaudible to the public. Note that this glissando comes before our starting note – it’s like an introduction to it – and therefore requires starting the bow also before the “correct” rhythmically stipulated moment.

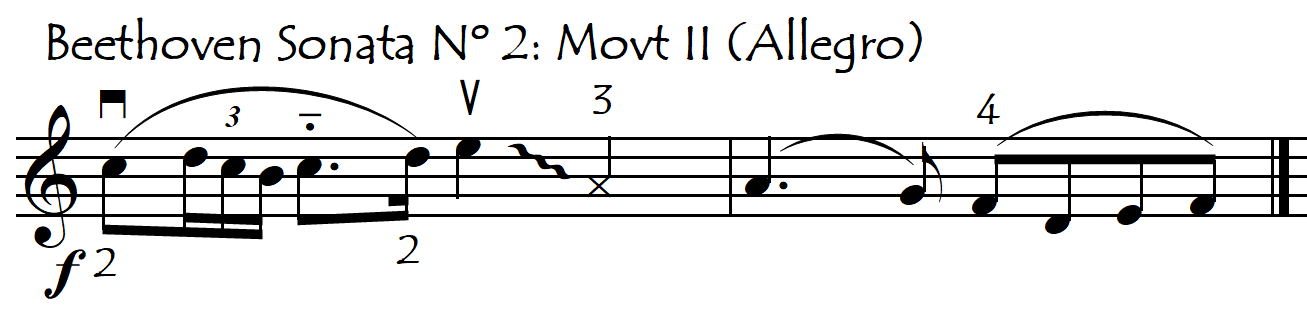

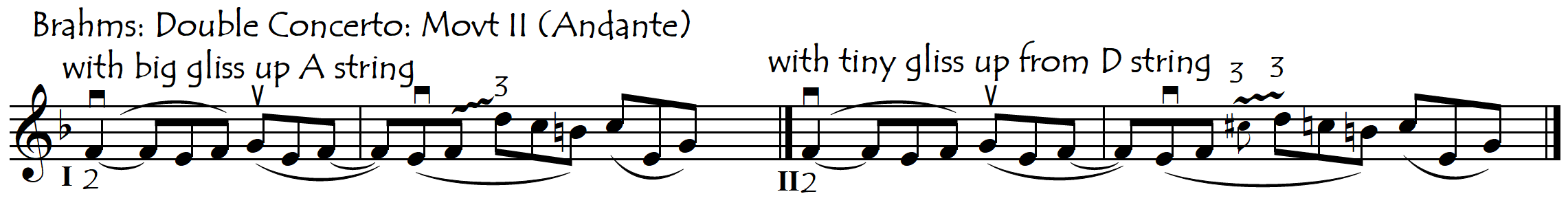

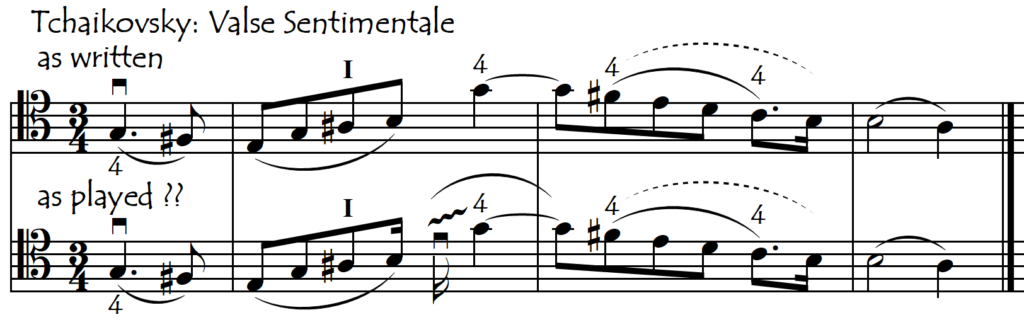

In the above example, our little glissando up to our high note was basically just an invaluable technical device, only audible to the ears of the player but not to the public. We can however also make this type of glissando quite audible, in which case it becomes a very potent expressive and stylistic device. The return, in the higher octave, of two of the themes shown in one of the above examples provides a good illustration of this:

This gentle anticipated slide/glide up into our note, with its gradual increase in bow speed and pressure, is a very sensuous way to start a note. It really is like a caress, and gives the music that liquid, unctuous, “extra-smooth” feeling. This is when music really starts to “melt in your mouth”, but just like with the delights of chocolate and honey, we need to use this technique with moderation! And in some musical styles it is not at all appropriate: this is definitely not a “Baroque” nor “Classical Period” technique, but is an absolutely vital element of Pop and Jazz interpretation.

THE SECRET “RESONANCE GLISSANDO”: A MAGIC TRICK

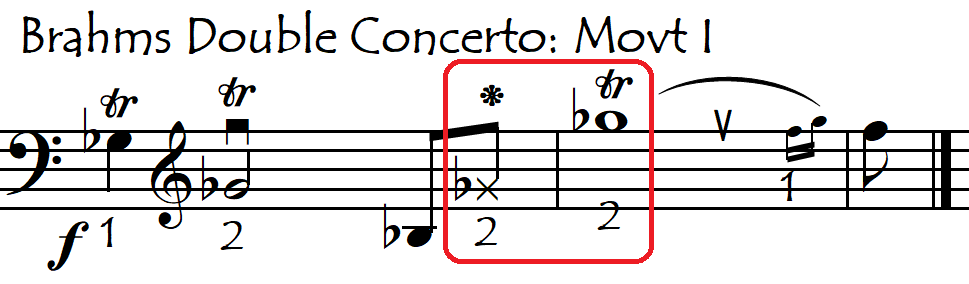

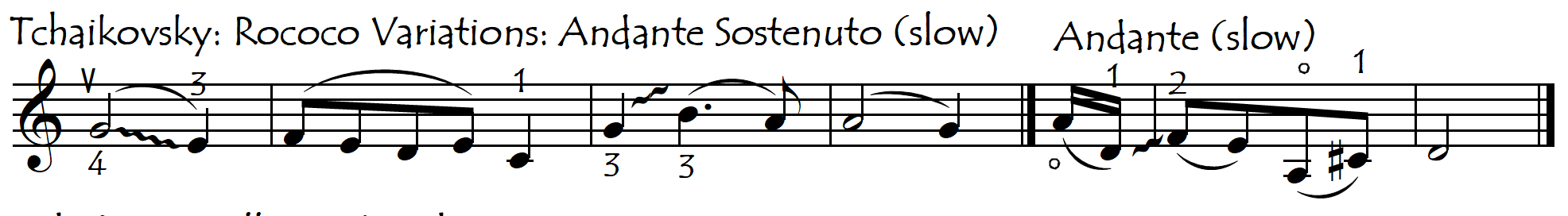

When we have a short rest, silence or musical breath before a supposedly silent shift on the same string, the resonance of the previous note is often sufficiently strong that we can use it to make a secret, privately-audible glissando to the following note. This glissando is not part of the musical line (because it occurs during a “silence”) and nobody will hear it except the player, but it can be an invaluable aid to finding the new note safely and surely. This trick works the best for same-finger shifts as any change of finger during the glissando will dampen the string’s residual resonance and risks making the glissando inaudible. In the examples below the notes with the “x” notehead are not articulated but are definitely heard by the cellist as the end (target/destination) of the glissando.

We can also use this “trick” for silent shifts to another string. Here, normally, our resonance glissando is on the “old” string (and the “old” finger), enabling us to find the new position accurately:

But sometimes we can use a special trick for a shift to a different string: by articulating our new finger on the new string hard and fast (“whacking“) before the shift, we can actually produce enough resonance on the new string to make the glissando audible on that string:

In order to allow the string to resonate (which is what makes our glissando audible), we need to lift the bow off the string during the shift. This means that this trick works best after upbows or, as in the above Tchaikovsky example, during a retake.

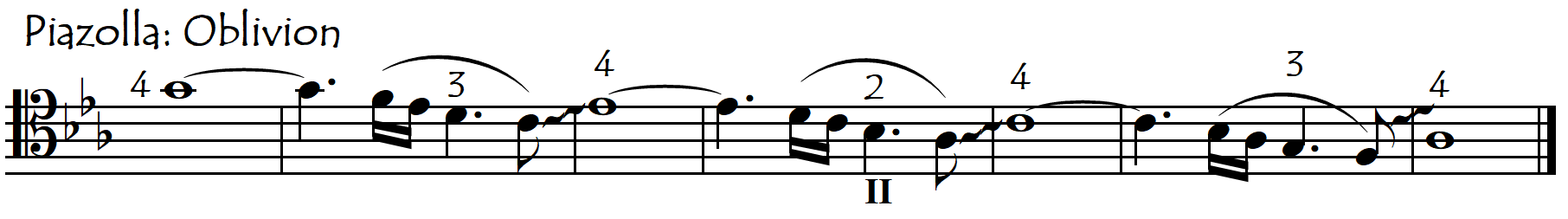

When shifting down to the Neck Region we normally don’t have as much need for the resonance glissando because we “know” where our notes are in this region. But when shifting down to notes in the Intermediate Region (or to thumbposition in any region) the resonance glissando can be very useful:

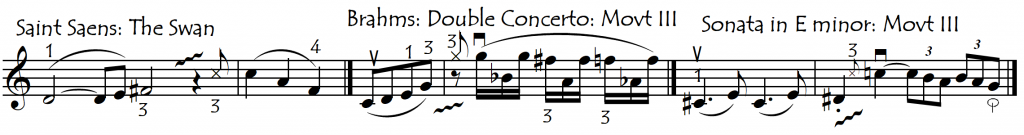

The following link opens a compilation of extracts from the cello repertoire for which the use of the “resonance glissando” can make our cellistic life very much easier:

Resonance Glissandi: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

THE GLISSANDO AS AN EXPRESSIVE DEVICE

In the above examples, we looked at how using an audible slide can help us to play more accurately and in tune. But the glissando is also a profoundly expressive device without which it is impossible to be an expressive string-player.

WHY ARE GLISSANDI SO BEAUTIFUL?

The use of glissandi, the connection of two notes by a left-hand finger slide, is one of the most beautiful expressive tools in music. This expressive power, that can make music so human, comes perhaps from an unconscious philosophical and emotional parallel with creating connections in life in general, not just between notes but between people, between peoples, between people and nature, and between the different conflicting elements within each one of us. A musician who doesn’t connect their notes (who doesn’t like glissandi) is a person who doesn’t look for connections. And an institution that doesn’t like glissandi is equally cold, aseptic, and unfriendly. How symbolic then – and how sad – to arrive for the first time in a professional orchestra and be told from the first day “no glissandi! ” (see Orchestral Playing).

FINGERING FOR GLISSANDI

Playing in a singing, lyrical style requires staying on the same string as much as possible (singers have only one) and joining the most appropriate notes with warm, tastefully calibrated glissandi. In both sentimental and dramatic music, some notes are literally begging for a glissando. In this type of music or phrase, an expressive musician will decide how and where to do their shifts exclusively for expressive reasons rather than for technical reasons. In fact, often we do a glissando into the new note even when a position change isn’t even necessary, purely for expressive reasons.

And we can even do a glissando while playing the very same note in order to make a harmonic change more expressive. Thus, not only may we do more shifts than technically necessary, but we might also make them very obvious, once again purely for expressive reasons.

We can even do a glissando without a shift (in the same hand position), by bunching up the fingers close together and then sliding up to the new, higher finger with a glissando even though we could have simply placed the new finger down without a glissando:

Repertoire examples for all these situations can be found on the Expressive Fingerings page.

CHOOSING OUR GLISSANDI: WHEN, WHERE, HOW MANY, HOW MUCH, AND WHY ?

GLISSANDI AND STYLE (HISTORICAL AND PERSONAL)

Even if we love glissandi, we mustn’t forget that the prominent expressive glissando is very much a romantic-and-afterwards phenomenon. Much of the music of the Classical and Baroque epochs (and before) was written for palaces and churches. Religious and royal decorum have never been renowned for their public shows of emotivity and sensuality and, in music of these styles, this expressive device is often inappropriate and will need to be avoided (see below, section 5: “Avoiding Glissandi”). Before the Baroque period, most of the stringed instruments including the Lira (Viola) da Gamba and Lira da Braccio (precursors of the cello and violin family) had frets, so even if they had all wanted to, the only musicians who could really join the notes together with glissandi were singers and sackbut players (the sackbut was a precursor of the trombone). For this reason, in music of these early epochs, we will probably use expressive glissandi only in passages that use a melodic, singing style (usually slow movements).

But these pre-romantic glissandi can be absolute magic. Upward shifts on a bowchange can be made hugely expressive – but in a very discreet way – if we shift on the old bow and on the new finger. This is a perfect technique for “Classical Period” music, for which the Romantic swooping glissando on the new bow is just too much (see also Shifting And The Bow). Christophe Coin is an absolute master of this type of shift.

This is such a beautiful and powerful expressive device that we may often want to use it even when a shift is not absolutely necessary, as in the second shift of the above example.

In Romantic music, however, we are in a different world and can go crazy, indulging, if we want, in an extravaganza of highly audible glissandi. In the cello’s first entry of the Lalo Concerto, we could easily do ten glissandi in 24 notes. Curiously, these glissandi are not on the larger intervals but are instead uniquely on the smaller intervals:

Choosing where and when to do our glissandi, and how prominent we will make them, is a lot like choosing what to wear, or what to say. It shows a lot, not only about our sense of style and our understanding of the different historical periods in music but also about our personality.

GLISSANDO UPWARDS OR DOWNWARDS?

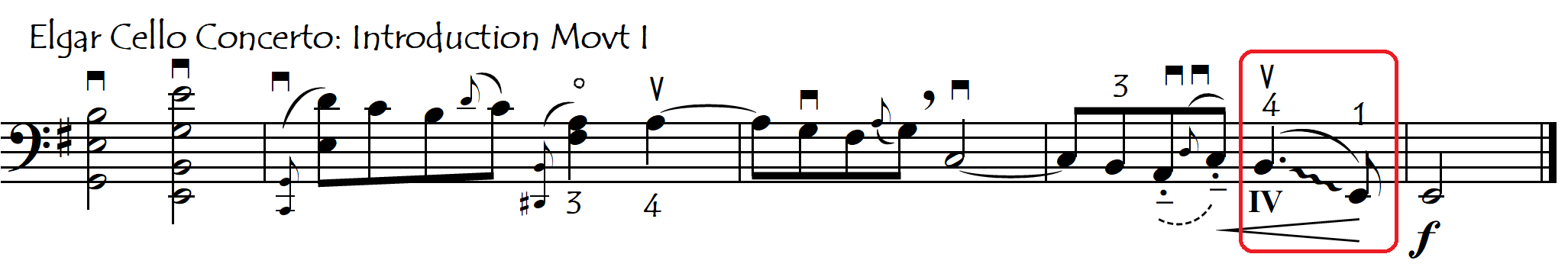

Why is it that we so often (but not always) favour expressive glissandos upwards into the new note rather than downwards? Perhaps it is because in music, as in life, going “up” is normally associated with a rise in energy, tension, motivation, success and excitement (working against the force of gravity), whereas going “down” is associated not only with release and relaxation but also with depression, failure and giving up (falling passively with gravity). Of course, there are many, many exceptions to the tendency to favour the upwards glissando. Perhaps the biggest, most “famous” downward slide is the closing cadence of the cello soloist’s introduction to the Elgar Concerto.

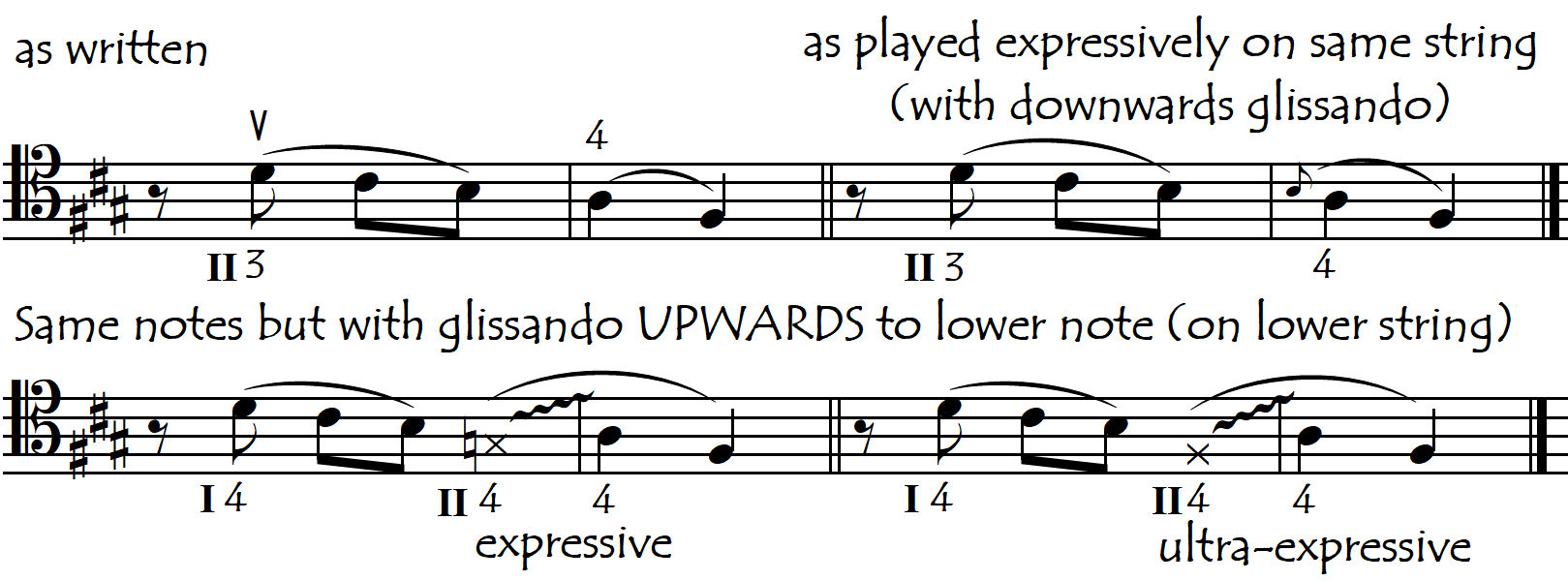

It is very curious that, even when our next note is lower than the preceding note, we can still slide “up” into it not only with perfectly good taste but even with great expressive effect. Perhaps the expressive effect is even greater when we slide up to the lower note (on the lower string) than when we slide down to it on the same string ?

Even when the pitch of our note doesn’t change we can do a slide up (but never down) onto the same note but now on a lower finger, usually to highlight a change of character or harmony:

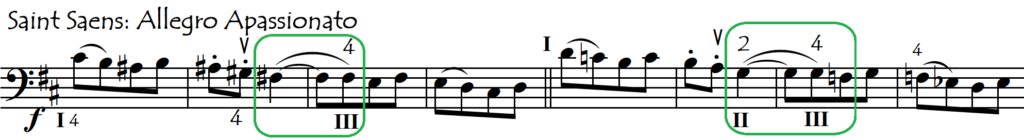

And we can do the same glissando upwards to the same pitch but this time on the lower string. This is a very large glissando (covering a great distance) so we normally do this to achieve a particularly dramatic, expressive effect:

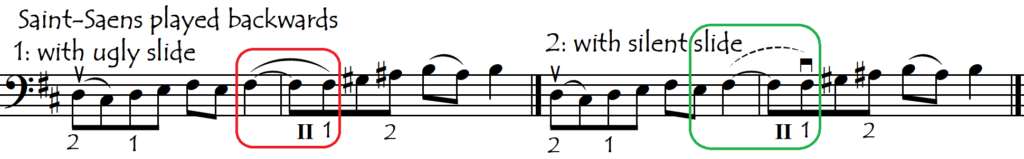

If we try and do this dramatic expressive effect with the equivalent downward glissando to the same note on the higher string, we will immediately discover why this type of fingering (effect) is basically never used: it is simply ugly, because of the downward glissando. The following example is the same Saint Saens excerpt but now played backwards. If we try and do the same effect of the very audible glissando to the same note on the higher string, the result is just plain ugly. For this reason, we will probably not make the shift legato and will prefer to “hide the slide” in the gap between the two portato pulsations of the second example:

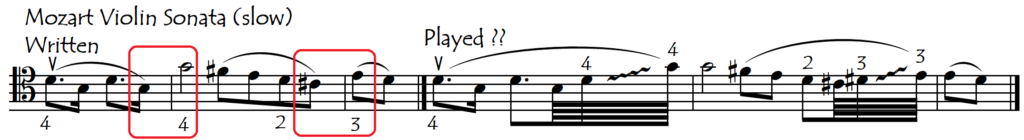

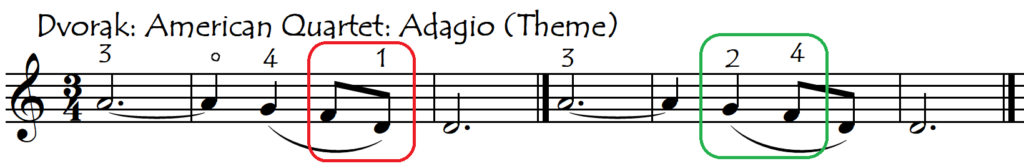

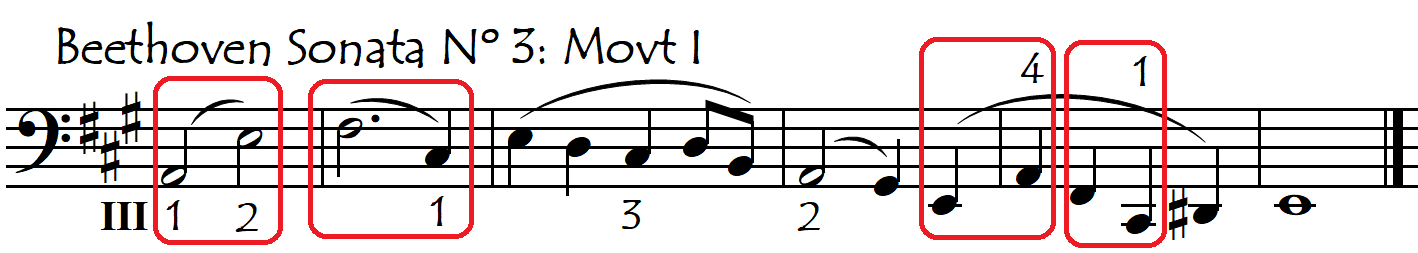

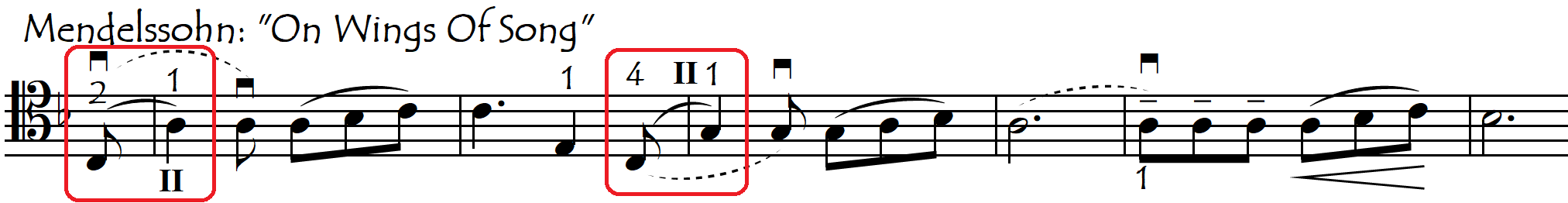

Most upward glissandi will sound good, even if we are only doing them to help us play our shift in tune. But the same cannot be said for downward glissandi. These need to be chosen with much more care because a badly-chosen downwards glissando has the opposite effect to a beautiful expressive device and can sound more like an ugly smear. The impact on the musical line is the same as if a beautifully-drawn line of a picture was suddenly smudged (smeared). Older musical editions tend to be full of fingerings that make these ugly smears unavoidable. But at other times, in our search for a safe and easy life, it is we who might choose a technically easy fingering which unfortunately comes with that ugly glissando included. The first fingering of the following excerpt is a good example of this, while the second fingering is an alternative in which a discreet glissando between the 2nd and 4th fingers is now a beautiful embellishment of the melodic line rather than an ugly disturbance:

HOW BIG IS ENOUGH ? HOW BIG IS TOO BIG ?

It is surprising how little distance we need to slide on to give the effect of an expressive glissando. Except for the most expressive, juiciest glissandos (such as in the Elgar example just above) and other special effects, we often don’t need to make our glissando cover (connect, sound) the entire distance between the notes. The important part of the glissando is mainly just the last little bit: the tone/semitone approach to our target note. In fact, audible glissandos that cover large distances – especially if played very prominently with the bow – can sound like simple technical aids and, as expressive devices, can be “over the top”, falling into the artistic category of “bad taste”. At the beginning of this article, we looked at how we can start notes after a silence with a little glissando that is rarely more than a tone and often only a semitone. If we make these little glissandos any larger (longer) then, rather than being beautiful expressive devices, they sound simply clumsy and ugly.

In order to give warmth and legato to our shift but avoid sounding like a beginner or a cheap crowd-pleaser, we will often reduce the audible prominence of the glissando (especially those covering the greatest distances) by using a relaxation of bow pressure and speed during the shift:

We can also choose to make our upward glissando to the higher string, taking a “short-cut” which not only makes a large shift distance smaller but also avoids the risk of our glissando sounding excessively long:

It is surprising just how expressive a small glissando to the neighbouring string can sound, mimicking almost entirely the glissando effect of a large glissando up the same string. Not only can a little glissando across to the higher string sound (almost) as expressive as its much larger alternative up the same string, but also it can give us much greater intonation security, especially for shifts up into the thumb region for which we don’t have much time to find our new note.

AVOIDING CONSECUTIVE GLISSANDI

Shifting with consecutive up-down (or down-up) glissandi both to and from a note (or position) will often sound ugly or in bad taste, especially if the shifts are close together in time. Rather than a bird singing, this is more like a bird swooping, or a roller coaster ride, and can make us feel a little seasick. Normally, when shifting both to and from a note (or position) we will choose only one direction for the prominent, expressive glissando. In the following example, from the Second Movement of Elgar’s Cello Concerto, we will “hide” the downwards shift (see below for how to do this) but will do exactly the opposite for the upwards shift immediately afterwards.

This one example illustrates beautifully the two concepts that we have just talked about:

This one example illustrates beautifully the two concepts that we have just talked about:

- avoiding a “double glissando”

- favouring the upwards glissando instead of the downwards one.

HIDING GLISSANDI

We have several ways to avoid audible, prominent glissandi between the notes:

- relaxing our bow speed and pressure during the shift. This idea works equally well for slurred shifts (see Portato Shifting in Shifts and the Bow) as for shifts on a bow change

- articulating the “new” finger directly on the destination (target) note rather than sliding into it

- changing our fingering (finger the passage across the strings, or finger it so that the shifts come on bow changes).

- for shifts on a bow change, by doing the shift on the previous bow it becomes much easier to hide

In the previous musical example (Elgar Concerto Movt. II), we can use the first two methods to reduce the prominence of the downward glissando. And we will do the exact opposite to bring out the upwards glissando!

ROMANTIC EXPRESSIVE GLISSANDI VERSUS CLASSICAL-PERIOD TECHNICAL GLISSANDI

In Romantic music, we will often want to make our glissandi particularly audible as they are an essential feature of our interpretation. For shifts on a bow-change, this is most easily achieved by placing our shift on the new bowstroke rather than on the old bowstroke. This requires that we anticipate our bowchange, starting our new bowstroke a little before the exactly notated rhythmic moment, as if the shift were a gracenote before the target (destination) note.

In music of the Classical and Baroque Periods, however, the situation is often the complete opposite: now we want to hide the glissando from the listeners as much as possible as it is probably stylistically inappropriate. We can do this by doing the shift on the previous bowstroke as here it is very easy to make this vital positional aid so inaudible that only we (the player) can hear it:

This subject is also looked at on the pages dedicated to Shifting And The Bow and Style and Epoch

THE FRICTION FACTOR IN SLIDING SHIFTS

Fingerboards need to be absolutely uniformly smooth. If our fingerboard (and/or strings) is too slippery, too sticky or simply not uniformly resistant to the friction of the sliding fingers on the string, then we can have all sorts of problems with the control of our sliding position changes (glissandi). Imagine a fingerboard with oil or soap on it: this would be too slippery. In the opposite (frictional) direction, fingerboards can sometimes be too resistant to the sliding movements of the fingers, which can happen if the fingerboard is not smooth enough. Also, some strings have a fairly rough winding on them which creates additional drag. The normal cause of excessive “drag” however is not a problem of poor workmanship but rather a problem of accumulated sticky filth!

Over time, fingerboards (and strings) – like carpets, clothes and any exposed surfaces – tend to accumulate all the dust and dirt to which they are exposed. If we don’t clean our strings and fingerboard periodically with alcohol (with a make-up-removal cotton pad, a cloth, tissue etc), then we can find our shifting seriously disturbed by this sticky mess. It is astounding the amount of black-brown goo that comes off after a few months – especially after hot weather – and it is equally astounding how much our sliding finger contact is improved after this cleaning operation. We do however need to be careful not to get alcohol on any part of the cello’s body except the fingerboard: alcohol will damage the varnish unless removed immediately.

CONCLUSION: THE GLISSANDO LABORATORY

The following link opens up a page in which we can look at any shift and work on it in increasing order of difficulty with respect to the help we get from the finger contact with the string and the glissando during the shift.