Chords On The Cello: Bowing Aspects

We usually consider chords as mainly a left-hand issue because putting several fingers down together on different strings at the same time (and in tune) poses definite problems (see Left-hand String Crossings). Here however we are looking at chords from the point of view of the bow. And here we are looking at “real” chords – not broken chords (which are looked at on the 3-string crossings and 4-string crossings pages).

The problems that chords pose for the bow are largely – but not exclusively – to do with the “bow-level control” (string-crossing) aspects.

TO SPREAD OR NOT TO SPREAD ?

There is no way we can play three or four strings simultaneously, so the question is not “to spread or not to spread?”, but rather “how to spread?”.

HOW TO SPREAD ?

SHOULDER LIFT, ELBOW FLAP OR WRIST PRONATION ?

A chord requires a rapid and extreme change in bow-level, almost always from the bottom strings to the top strings. We can do this string crossing in several different ways: either with a whole-arm movement from the shoulder and back, a whole-arm movement from the elbow, or with a much more economical movement of pronation of the bow hand (which only works at the frog). We can of course also combine these three different movements in different proportions. Lluis Claret, a Zen master at the cello, proposes, for typical downbow chords in the lower half of the bow, wrist pronation rather than elbow flapping.

SPREAD ACCORDING TO MUSICAL EPOCH/STYLE: ROMANTIC SANDWICH OR BAROQUE-AND-ROLL ?

Almost all chords are spread from the bottom to the top but we need to decide whether we will “roll” from the bottom string over to the top string, in a linear curve, one string at a time as it were (choosing our degree of overlap) or if, on the contrary, we will play the chord in two clearly distinguished blocks (the two bottom strings double-stopped, followed by the two top strings double-stopped). We can call this last way of playing chords the “2+2” way.

Our choice between these two alternatives is largely dictated by style (historical period). Normally in music of the Romantic Period, a loud dramatic chord would be likely to be played “2+2”, whereas in Baroque and Classical Period music, chords are more likely to be “rolled” (arpeggiated, spread), especially for softer chords but even also for loud, dramatic ones.

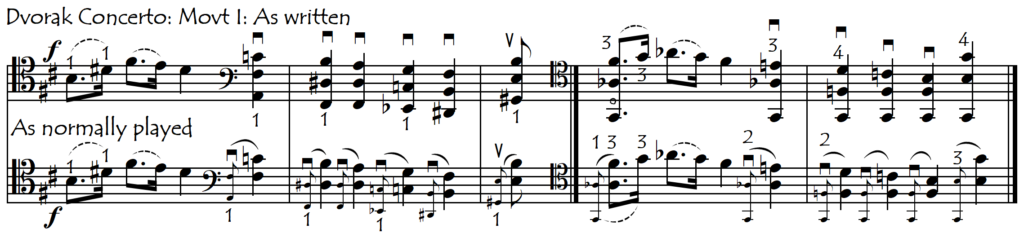

These differences can be best shown by looking at some repertoire examples. Let’s start by looking at the typical, loud, dramatic Romantic “2+2” spread chord of which the Dvorak Concerto has many examples:

In the above example, we have very few doubts or questions about how to spread the chords: almost every cellist spreads the chords in the “2+2” way, playing the bottom two notes of each chord before the beat and the top two notes on the beat. But not every musical situation is as clear as this one. We sometimes (often) will need to make a conscious decision as to which notes of the chord we want to place on “the beat” (pulse). Normally the lower notes come before the beat, like an appoggiatura, while the top notes come on the beat, but there are exceptions. Sometimes we may choose to play the bottom notes of a spread chord on the beat, instead of before the beat. And, independently of whether we play those first notes on or before the beat, we also always have a choice as to how long we make those first notes of the spread:

Sometimes we have no choice as to where we place the first two notes of the spread. For example, on the chord of the third beat of the second full bar, we must play the bottom two notes before the beat because of the sfz and crescendo on the top note of the chord.

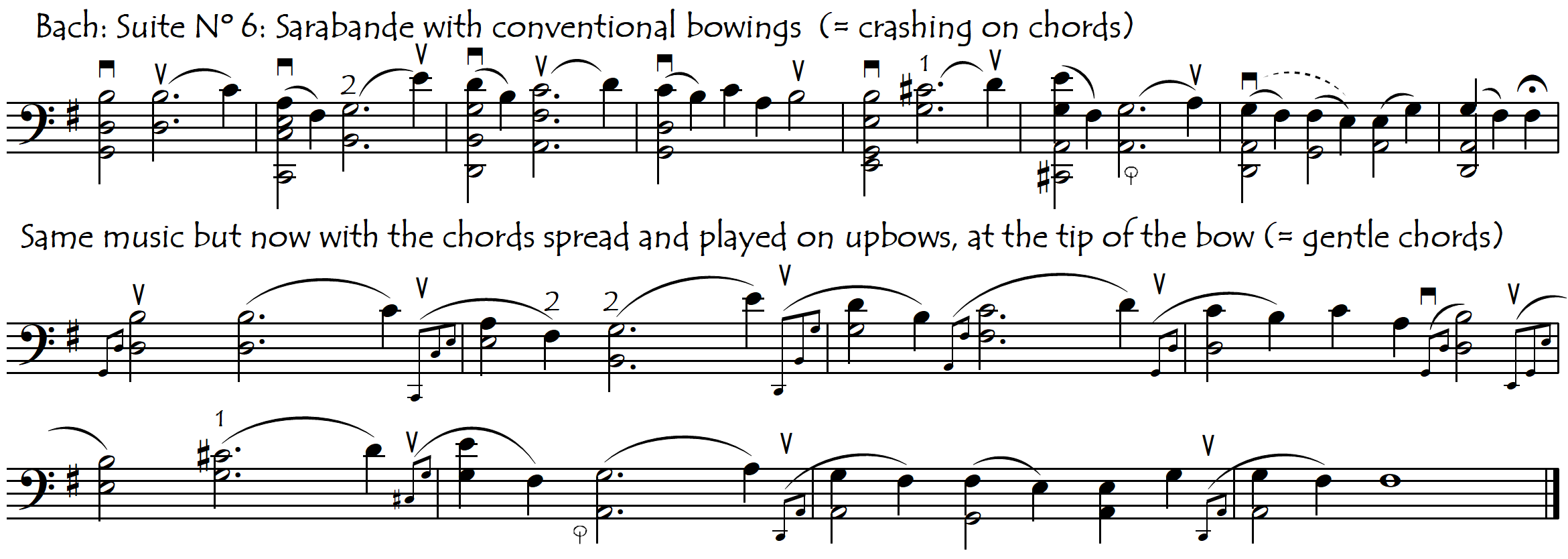

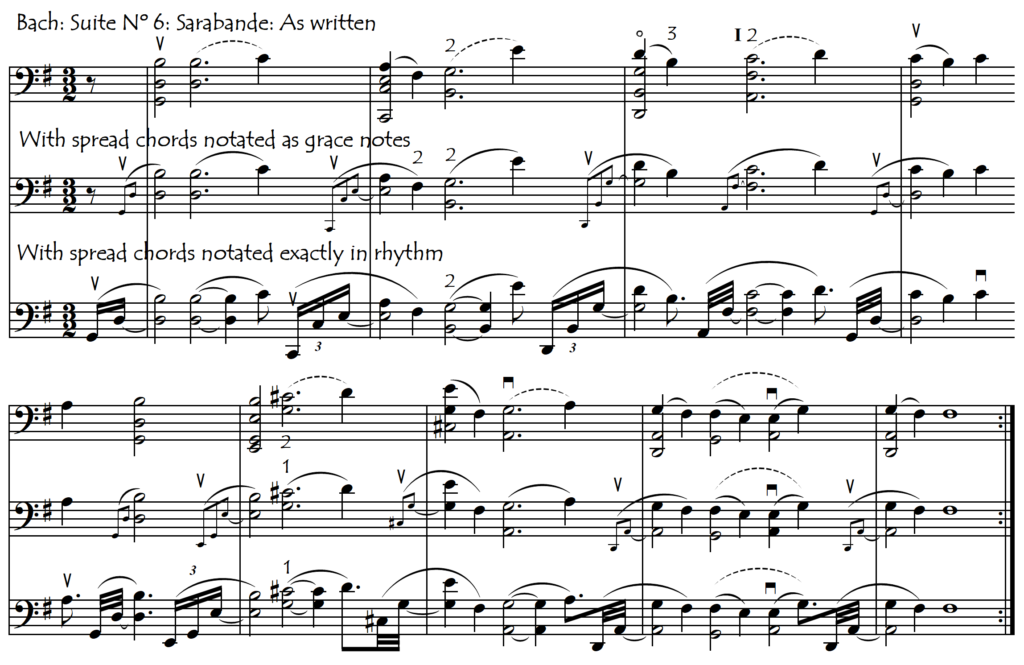

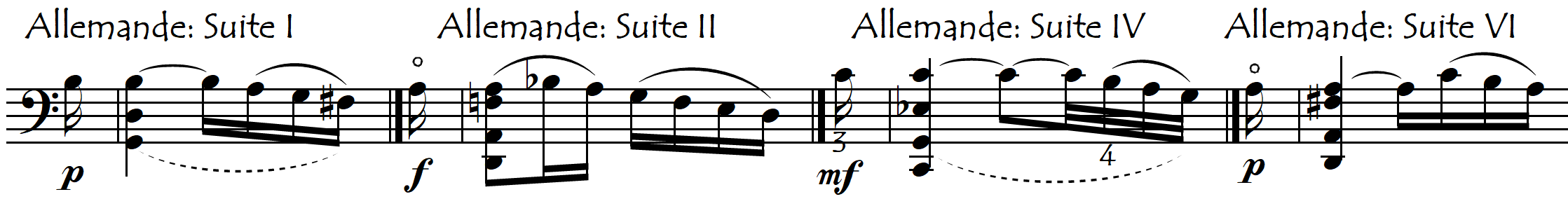

At the opposite end of the roll/sandwich spectrum are the many gentle arpeggiated purely-rolled chords of the Bach Suite Sarabandes and Allemandes (especially in the Sixth Suite). If we want to notate this rolled spreading, we have several choices:

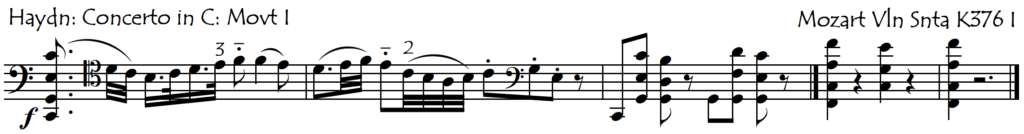

These Bach chords use a very gentle spread, but other more vigorous chords from the Baroque and Classical periods can make use of a much faster, more energetic roll (spread). The dramatic loud opening chords of the Haydn C Major Concerto and Mozart’s Violin Sonata K376 probably benefit stylistically from being rolled (arpeggiated) in that way. If we play “Classical” (or earlier) chords “2+2” we often risk making the music sound overly “Romantic”.

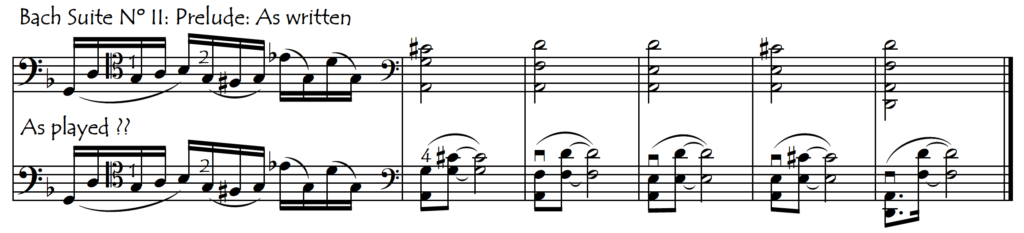

Of course, every “rule” has its exceptions and the Bach Suites (and Unaccompanied Violin music) are full of these exceptions. The chords at the end of the Prelude to his Second Suite are so dramatic that they definitely seem to want to be played in the romantic “2+2” sandwich manner:

DYNAMIC ASPECTS OF THE SPREAD

Another variable in chords is the possible difference in dynamic between the bottom and top of the chord. In dramatic Romantic-period chords, we will often want to start the chord with incisive power on the bottom notes even when (as is most often the case) the bottom notes serve as an apoggiatura before the top notes (which come on the beat). In “Classical” and “Baroque” music however, even “forte” chords often benefit from a slightly gentler start on the lower strings, which allows us to do a crescendo as it were towards the top notes of the chord. Try the opening of the Haydn C major concerto in this way. It suddenly sounds “better” – more in style – as well as being easier to control.

THE CRASHING BOW

Chords are nearly always played starting from the bottom, and most chords are played on a downbow. This means that for cellists, unlike for violinists/violists, the string crossing direction in chords is in the “unfavourable” “anti-natural” direction (see “Bow’s Natural Crossing Tendencies“) which is one of the reasons why it’s so easy to crash them. Downbows prefer so much more to go towards the lower strings. Try playing some loud dramatic chords with the spread now in the opposite direction (starting from the top strings like violinists/violists): we can immediately feel a large difference in ease of control and understand how much more ergonomic it is to play chords in this way. This is one of the reasons why gentle, spread chords on an upbow are such a delight to play (see the Sarabandes from the Bach Cello Suites).

The easiest and most natural way to play downbow chords is loudly and with a big accent on the bottom notes, as for example in the Dvorak Concerto example above. It is much more difficult to start downbow chords gently and softly, partly because the speed (and control) of the string crossing across to the higher strings is easier to achieve in a forte attack than with a gentle pp start. This problem of the fast string crossing is especially important when the chord has a short, rapid upbeat on the higher strings (which occurs very often) in which case not only do we need to get quickly from the lower strings to the higher strings after the start of the chord, but also we need to get quickly from the top to the lower strings just before the chord.

In loud chords, the crunchy explosive crashing start is not necessarily a big problem, but in soft chords we definitely don’t want any of this. There are various possible solutions as to how to avoid the crunching starts to soft chord:

- practice hard on this specific problem in order to develop great “chord bow control”. The Sarabande and Allemande from Bach’s Sixth Suite are very good study material because they contain many chords, and almost all of these need to be played very gently

- in some very gentle chords we may prefer to play them on an upbow to avoid the crashing, thus avoiding instantly the need for delicate bow control

- systematically roll (arpeggiate) our soft chords rather than spreading them. This is also easier on upbows.