Cello Fingerboard Regions: The Intermediate Region

This is a sub-page of the Cello Fingerboard Regions page.

Between the “Neck Region” (the low regions) and “Thumb Region” (the high regions) there is a frontier zone, a strange no-mans-land, that we could call the “Intermediate Region”. On the A-string, this region extends approximately, from the first finger on E (Mi) up to the first finger on A (La), perhaps even a little higher. On the other strings, it concerns exactly the equivalent positions.

The upper limit of the Intermediate Region is, by definition, the position in which we can no longer play without bringing our thumb up onto the fingerboard. This upper limit will be variable for different cellists and for different cellos because it will vary according to the size and flexibility of the cellist’s hand, as well as with the size of the cello we are playing and where we place our thumb (see below). Perhaps we could add an 8th Position, with the first finger on B and the third finger on D (on the A-string). The lowest position of the Intermediate Region is the highest position of the Neck Region. In other words, what we traditionally call the “Fourth” Neck Position is simultaneously the upper end of the Neck Region and the lower end (start) of the Intermediate Region.

In this “Intermediate Region”, suddenly and uniquely, the hand and fingers move up and down the fingerboard independently from the thumb (which is usually blocked in the corner of the cello neck). In fact, it is this characteristic of the thumbs hand posture that defines the Intermediate Region.

When we reach the Intermediate Region, we have left our familiar, comfortable earth (the Neck Region), and are now on a strange and bizarre planet. Although gravity is unchanged, our hand posture, shifting movements, and positional sense are suddenly quite different to those of the neck region. Apart from the blocking of the thumb, one of the most important differences is that the fourth finger becomes more and more uncomfortable to use as we go gradually higher in this region (it is simply too short). Thus, we now have only three available fingers and must therefore use, for the first time, the 2-3 tone extension. Particularly in the lower Intermediate Region, this extension usually feels very strained and unnatural, especially for small hands, which is why we might want to continue using the 4th finger not only in the 2nd intermediate position but also in the 3rd and sometimes even higher (see below and “Use of Fourth Finger in The Intermediate Region“)

For all these reasons, we can feel uncomfortable, insecure and unsure of where we are in this region. In fact, this region corresponds very well to the singer’s “break”: that difficult transitional register between their low and high registers which is often a problem both to pass through and to sing in.

THE VARIOUS POSSIBLE POSITIONS OF THE THUMB IN THE INTERMEDIATE REGION

Most of the difficulties of this region on the cello are due to the thumb being “stuck” (blocked) in the 90º angle formed where the cello’s neck curves around into the piece of wood that is called the neck block. This part of the cello is sometimes called the “crook” of the neck. Violinists and violists face exactly the same situation when they go into their higher positions. Fortunately however, we cellists (and bassists) have three other possibilities with regard to the position of the thumb that violinists and violists don’t have. Unlike them, we are not obliged to keep the thumb blocked behind the crook (corner) of the neck, and can alternatively choose to:

- put the thumb up on the fingerboard, using it as a finger (“thumb position”) or

- release it from its position behind the cello neck and let it “float” in the air

- release it from its position behind the cello neck and place it instead on the edge of the cello’s body.

What we do with the thumb in this region usually depends on the context: where we are going, where we are coming from, and at what speed.

Keeping the thumb in the neck crook gives us a very strong, secure positional sense (we know where our fingers are relative to the fixed reference of the thumb) and great postural stability. However, this can be at the price of increased hand tension, especially as we go higher where the fingers are at a greater distance (stretch) from the thumb, especially in major third extensions, and especially for small-handed cellists. As always, we must do a permanent balancing act between the contrasting (opposing) needs for freedom, on the one hand, and security (attachment) on the other. (see “Freedom Or Security“). We must weigh up the relative need for each in any particular passage and organise our thumb choreography accordingly.

Let’s look in more detail now at the different possible situations (positions) for the thumb in the intermediate region:

1. THUMB BEHIND THE NECK BLOCK (CROOK)

When we are playing in the Intermediate Region, this is the most common position for the thumb. Here, the thumb has an absolutely secure resting point which serves not only as a stable anchor but also as an unvarying positional reference on any particular cello. The only problem with this position is that, as our fingers play higher and higher up the fingerboard, our hand strain and discomfort increase because our thumb is stuck in this angle and cannot go any higher to accompany the rest of the hand. For cellists with large and/or flexible hands, this may be not very problematic, but for small-handed cellists, this strain can be a major problem when playing in the higher Intermediate Region.

One way to reduce this thumb-induced hand strain is to put the thumb up on the fingerboard (thumbposition, see below), but if we are just making a brief excursion up into the Intermediate Region and then going immediately back down again, it is likely that putting the thumb up on the fingerboard will probably be a significant disturbance to our hand’s stability. Fortunately for these (very common) situations, there is a huge difference in hand comfort and ergonomy between the two extremes of having the thumb deeply behind the neck or having it just lightly touching the edge of the neck block (“crook”) with its tip. By bringing the thumb out from behind the crook as far as it can (without losing its secure contact), we can significantly reduce our hand strain.

Violinists and violists have exactly the same problem in their higher positions. In fact, everything above “Fourth Position” for them could be considered as their “Intermediate Region” because they, unlike cellists and bass players, cannot use thumbposition.

2. THUMB UP ON FINGERBOARD (THUMBPOSITION):

Fortunately for cellists (and double-bassists), we have another option for resolving this problem of thumb-induced tension in the Intermediate Region: we can completely eliminate it by placing the thumb up on the fingerboard (thumbposition). The distances between the fingers in this fingerboard region, unlike in the lower Neck Region, are perfectly suitable for playing in thumbposition which means that it is often more comfortable and practical to bring the thumb up onto the fingerboard and use it like an additional finger, rather than to shift around trying to play all the notes with only three fingers.

But even when we don’t actually need it as a “playing” finger, it can be helpful to bring it up onto the fingerboard, mainly because it holds the strings down and makes our finger articulations easier, especially when crossing to a different string:

There is often great advantage to be had by bringing the thumb up on top of the fingerboard in the Intermediate Region in passages that move up from the Neck to the Thumb region, especially at high speed. In this way, we avoid the awkward Intermediate Position hand postures completely by going directly from Neck Position to Thumbposition. Likewise for the reverse direction: coming down from the higher regions we may prefer just to keep the thumb on top of the fingerboard and stay in thumbposition until we finally get down into the Neck Region:

3. FREE-FLOATING THUMB

In slower passages, we have less need for the positional reference information and postural stability that the thumb provides. This allows us to give priority to absolute comfort, releasing the thumb from all contact with the neck or fingerboard, just letting it float to remove tension from the hand. This idea is equally valid in all three fingerboard regions – neck, intermediate and thumb (see Freedom versus Security). In faster passages that are continuing on higher up into the Thumb Region, it is often best (safer, more secure, more ergonomic, easier) to “forget about” the Intermediate Region and just shift up to the notes in that region with the thumb free-floating, ready to be put onto the fingerboard:

4. THUMB ON EDGE OF CELLO BODY (RIB):

When we leave the thumb in the crook of the cello neck, the hand can be under considerable tension in the intermediate region, especially in the higher intermediate positions where the fingers are at a greater distance (stretch) from the thumb. Not only is the hand strained and tense, but its posture also becomes increasingly unnatural as we move higher up the fingerboard, because the thumb’s fixed position, far behind the rest of the hand, ultimately makes the hand (fingers) point more and more towards the bridge. These two problems are especially significant for smaller hands. To reduce this tension and thus allow the hand posture to be more natural, we can place the thumb on the edge of the cello rib, where the side (rib) meets the belly (top-plate). This could be considered a compromise, a “half-way-point” between the free-floating thumb and the thumb stuck in the crook of the neck.

This placement of the thumb gives security and stability while also diminishing the tension in the hand, especially in the higher intermediate region positions. It facilitates the 1-3 major third extension, as the hand can stay more square with respect to the fingerboard.

This position of the thumb also favours the use of the fourth finger in the lower intermediate positions as well as allowing us to play more with the fingerpads rather than on the fingertips (because it allows the fingers to be flatter). The reduction in hand tension also greatly favours our vibrato. It is very useful for passages that stay for a longer period of time notes in the Intermediate Region or that continue on upwards into the thumb region. In the following examples the “R” means “place thumb on cello rib”:

The reduction in hand tension achieved by placing the thumb on the side of the cello rib not only makes the highest notes of the Intermediate Region more comfortable but also extends the range of our Intermediate region, allowing us to go further up the fingerboard before we need to put our thumb up (thumbposition). This can be a great advantage in passages that shift up to C#/D (on the A-string) but then go immediately back down into the Intermediate/Neck regions because by eliminating the need to go into thumbposition we keep a much more secure positional reference:

All of these advantages become even more pronounced if we allow the thumb to move further out on the cello rib because the further the thumb is away from the cello neck, the less tense the hand becomes. Try the previous examples with the thumb in all of its six (!) possible Intermediate Region positions: behind the crook, on the edge of the crook, on the cello rib but touching the neck block, wide out on the cello rib (as far from the neck block as you need in order to achieve maximum hand-tension reduction), up on the fingerboard (in thumbposition), and free-floating. If we play these previous examples transposed onto the lower strings, in exactly the same hand/fingerboard positions, we will see that this placement of the thumb wide out on the cello rib is especially helpful on the A-string, somewhat less useful on the D-string and not particularly necessary or helpful on the G and C-strings.

Unfortunately however, for passages with frequent shifts between the lower and higher Intermediate region, the change of the thumb’s position from behind the neck to up on the rib can create considerable insecurity. In the following example the green enclosures indicate passages in the lower intermediate region where the thumb will want to be behind the cello’s neck. while the red enclosures show the higher passages for which the smaller-hand cellist may prefer to have the thumb up on th cello body (rib).

Moving the thumb between each of these two positions requires a momentary loss of contact between the thumb and the cello as the thumb finds its new position. This is extremely destabilising for our positional control (intonation). Where possible, therefore, it can help to do this thumb movement just before, or just after (but not during), the shift.

I must confess that I am the only cellist I know who frequently uses this position of the thumb on the side of the cello’s body. It is therefore quite possible that it is most useful for cellists with small and inflexible hands. Diligent practice in the higher intermediate region with the thumb maintained in the crook of the cello neck will certainly increase the strength and flexibility of our hand and thus increase the size of the useful “tension-free” space between the thumb and the fingers, thus allowing us greater comfort and freedom in this problematic fingerboard region.

HAND ORIENTATION (ANGLE) IN THE INTERMEDIATE REGION

As in the Neck Region, we have two basic alternatives with regard to our hand posture in the Intermediate Region:

- “violin” posture: with the hand and wrist turned (sloping) backwards, the fingers pointing very much towards the bridge, and the first finger strongly curled.

- “double-bass” posture: with the hand flatter (in the same plane as the fingerboard), the fingers more square to the fingerboard, and the first finger more straight.

Compared to the Neck Region, the Intermediate Region hand posture will tend naturally much more to the “violin” posture than to the “double-bass” posture because of the effect of having the thumb “behind” the hand, which naturally and inevitably turns the hand into this “violinist” position. The “violin” posture is favoured by the following circumstances:

- playing high in the Int Region

- keeping the thumb back in the crook of the cello neck

- having a small hand and/or a short thumb

The “double-bass” posture is favoured by the opposite circumstances:

- playing low in the Int Region

- bringing the thumb up to the cello rib or simply releasing it

- having a large hand and/or a long thumb

PREPARING THE HAND HANGLE BEFORE SHIFTING UP TO THE INTERMEDIATE REGION

In the higher Intermediate Region, our hand will be normally in the “violin posture”. For secure, comfortable shifting up to these positions, it helps to have the hand already in this “violin posture” before our shift up. This is made easier if can avoid the use of the fourth finger just before our shift up because the fourth finger tends to pull our hand into the “doublebass posture” (more square to the fingerboard):

**************************************************************************************************

THE USE OF THE INTERMEDIATE REGION IN DIFFERENT MUSICAL EPOCHS

In the Pre-Baroque and Early-Baroque periods, the upper limit of the cello’s range was usually only the “A”, one octave above the open “A” string. What’s more, it would appear (from the type of writing we normally find), that this note was usually played as a harmonic. In other words, the Intermediate Region (with Intermediate Region hand posture and fingerings) was thus not really used at all in this period and the cellists left hand stayed in the Neck Region posture constantly, including its occasional excursions up to the mid-string harmonic. We can see this limited “Baroque range” in the Sonatas of Vivaldi, the first five Bach Solo Suites, the Sonatas of Marcello, Geminiani, Galliard, de Fesch etc.

Curiously, the violin at this period was also usually limited to this same physical range, with its highest note also being normally the E, one octave above the open “E” string. In fact, this limited range continued for the violin throughout the early Classical period (until when? Beet sonatas, Moz concertos?).

Towards the end of the Baroque period however, cello writing started to extend its range up into the Intermediate Region, taking the cellist’s left hand now up to “C” (or C#) on the A string, which is the highest possible position which can be used without having to obligatorily bring the thumb up onto the fingerboard. Bach (1685-1750) takes us up to this position only once, in the Prelude of the Sixth Suite. Likewise in the Partitas and Sonatas for Solo Violin he takes the violinists left hand up to the equivalent height only three times and each time very briefly (once each in the Chaconne, and in the Fugue and 4th movement of the C major Sonata).

However other composers – most notably the cellist composers of the Late-Baroque and Early-Classical periods – take us up into the Intermediate Region both earlier and much more frequently than Bach and most of his contemporaries. They were anticipating one of the principal characteristics of the evolution of cello writing through the ages: its gradual emancipation from the bass register and harmonic accompaniments towards a more melodic, lyrical and soloistic role. From the 1690s, Scarlatti in Italy was already dividing the bass line (basso continuo) into 2 separate staves, with the additional stave being for the cello, whose new voice was simultaneously becoming more active and rising into a higher (tenor) register voice than that of the bass part.

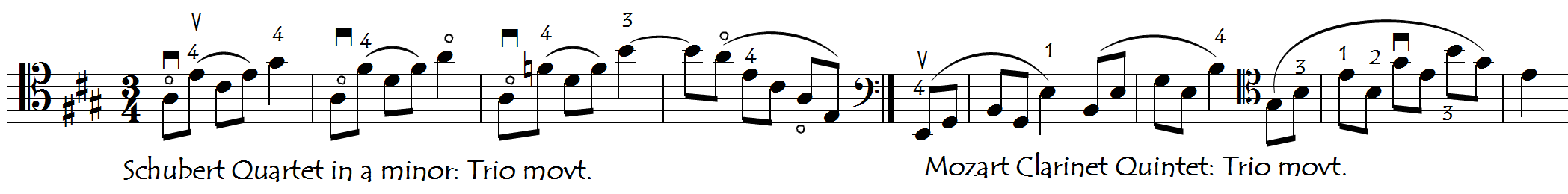

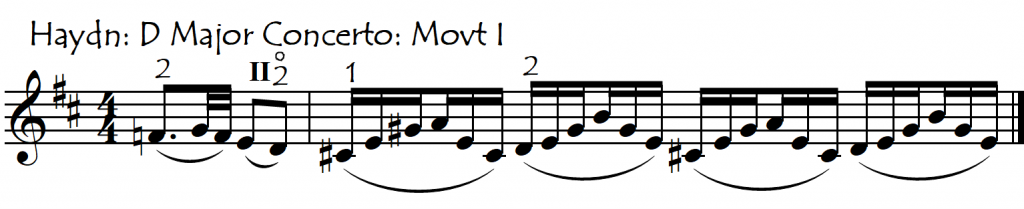

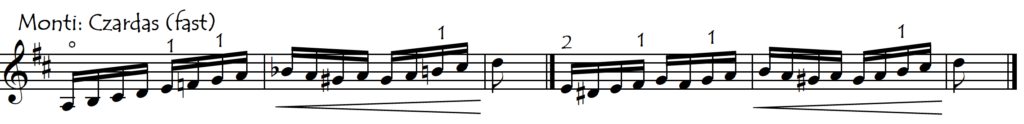

As mentioned in the Left-Hand Regions home page, a typical phenomenon of music of the Classical Period is that, after long periods confined to the Neck Region, composers often take us up to the Intermediate Region for brief climactic incursions, as the culmination of a phrase or of a movement as in the following examples.

It’s such a shame to mess up our big moment. To really feel secure and at home in this region requires specialised practice because, just as with the Thumb Region, in most standard repertoire we just don’t spend enough time in this region to really get comfortable here. Therefore we need to work on our Intermediate Region in an isolated, concentrated way, in the same way as we also need to work on our Thumb Region.

EXTENSIONS IN THE INTERMEDIATE REGION

In the Intermediate Region, the 1-2 tone extension is not usually a problem for even the smallest hand. Not only is the distance of this extension smaller up here than in the Neck Region but also our sloping hand angle (posture) in the Int Region actually favours this 1-2 extension. However, for smaller hands, the 2-3 tones and 1-3 major thirds, especially in the lower Intermediate Region, may never feel comfortable. These extensions can often be avoided by using alternative fingerings. These alternative fingerings are like double bass fingerings and will usually involve either:

- the use of the thumb (thumb position)

- a combination of the use of the “closed” hand position with more frequent shifting (= “double-bass fingerings”)

- the use of the fourth finger

Click on the highlighted links for repertoire examples and specific exercises for these fingerings.

THE USE OF THE FOURTH FINGER IN THE INTERMEDIATE REGION

It is curious how traditional cello fingering makes such a sudden radical frontier break across a tiny semitone distance on the fingerboard at the start of the Intermediate Region. From the systematic use of the fourth finger for the top note of the first intermediate position (F, F#, G, G# on the A-string) we proceed to the systematic and exclusive use of only the third finger (and the consequent total elimination of the fourth finger) for the top note of the position only one semitone higher (F#, G, G#, A). This “break” is a cellistic equivalent of former Eastern Europe’s “Iron Curtain”, separating two vastly different and mutually impenetrable worlds: on the one side “you can”, and on the other “you can’t”, and there is no transition zone between the two! The Iron Curtain collapsed because it was a ridiculous, artificial, unsustainable frontier. Do the ergonomics of the left hand in this fingerboard area really justify a similar radical break in our fingering systems or is this frontier also artificial and unnecessary?

We have a special page dedicated to this question and to the use of the Fourth Finger in the Intermediate Region in general. Click on the link to explore this subject further.

SPECIFIC BASIC PRACTICE MATERIAL FOR GETTING COMFORTABLE IN THE INTERMEDIATE REGION

It is only when we are comfortable playing in each Intermediate Region hand position can we hope to be able to shift accurately and comfortably to and between the positions in this fingerboard area. The pedagogical order of our study material could be:

- always in Intermediate Region, no shifts

- always in Intermediate Region, with shifts

- with shifts to and from Intermediate Region

As usual, we can divide our practice material into “mechanical exercises” to start with, “music” to finish with and “studies” being a halfway point between the two.

1: EXERCISES WITH NO SHIFTS: WORKING EACH POSITION AND EACH FINGER CONFIGURATION

So, here, to start with, are some purely mechanical exercises for getting really comfortable in each position of this region. These exercises are definitely not “music”. This is the equivalent of a swimmer swimming laps. To swim really well, it is not enough to “know” how to swim: a swimmer has to put in hours and hours of physical, muscular, repetitive mechanical “practice”. Swimmers can switch their brains onto “standby mode” while doing laps. We cellists can switch off our emotions entirely in these exercises, but not our brains, as we need to control (check) our intonation and to know, at all times, what notes we are playing. It is this knowledge, this awareness, that reinforces our interiorised map of the fingerboard, which is especially important in this “bizarre” part of the fingerboard.

These first exercises are good for warming up. They snake chromatically through the entire Intermediate Region without ever requiring shifts. They are progressive in the sense that extensions are progressively incorporated. The first exercises use the effortless “close position” (with a semitone between each finger). The next exercises incorporate the 1-3 minor-third (simple) extension hand frame in which we have a whole tone between either the first and second fingers or between the second and third fingers. The final, most strained exercises, use the major-third hand frame in which we have a whole tone between both the first and second fingers and between the second and third fingers.

Intermediate Region Basic Positional Exercises: Fast and Fluid: NO SHIFTS

Intermediate Region Basic Positional Exercises: In Double Stops: NO SHIFTS

Now we will incorporate shifts, firstly within, and then subsequently to and from, the Intermediate Region.

2: SHIFTING WITHIN THE INTERMEDIATE REGION

Here we consider the “fourth” neck position as being also the first intermediate position because the thumb is here in its home base from which the hand (fingers) will now climb alone up into the higher intermediate positions.

Shifting Within the Intermediate Region: Same-finger Stepwise: EXERCISES

Shifting Within the Intermediate Region: Assisted Shifts: EXERCISES

Shifting Within the Intermediate Region: All Finger Choreographies and Intervals: EXERCISES

Miscellaneous Repertoire Melodies IN (mostly) the Intermediate Region

Mozart’s Melodies IN (mostly) the Intermediate Region

3: SHIFTING INTO (AND OUT OF) THE INTERMEDIATE REGION:

Doublestopped Arpeggio Shifts To the Intermediate Region: No Double Extensions: EXERCISES

Doublestopped Arpeggio Shifts To the Intermediate Region: With Double Extensions: EXERCISES