Choosing Bowings for Unbalanced Figures

This article is a sub-page of the “Choosing Bowings” “Bowspeed” and “Bowdivision” pages.

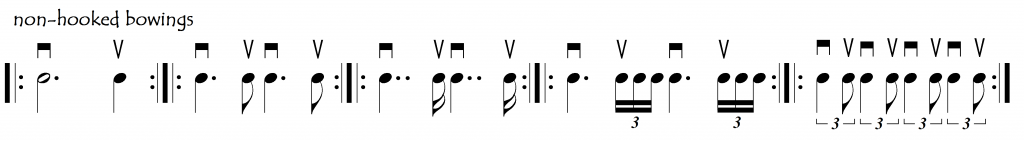

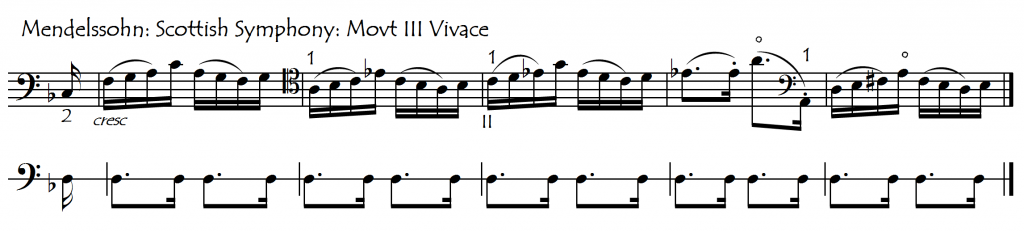

Sometimes the bowings/phrasings that composers specify have the deliberate effect of creating asymmetries in passages that would otherwise be simple and symmetrical. In these situations, changing the bowing to facilitate a more even distribution of bowspeed (bow division) may not be advisable:

Apart from these special situations of deliberate asymmetry however, we will normally try to plan our bowings to avoid sudden and extreme changes in bow speed. This planning can be especially necessary for repeated note sequences (rhythmical figures) in which the alternation of long and short bowstrokes creates “unbalanced” figures for which “as-it-comes” bowings (with a simple alternation of down and upbows) would lead either to:

- the bow being inexorably pulled to a place where we don’t want it to be or, in order to avoid this

- the making of huge unwanted accents.

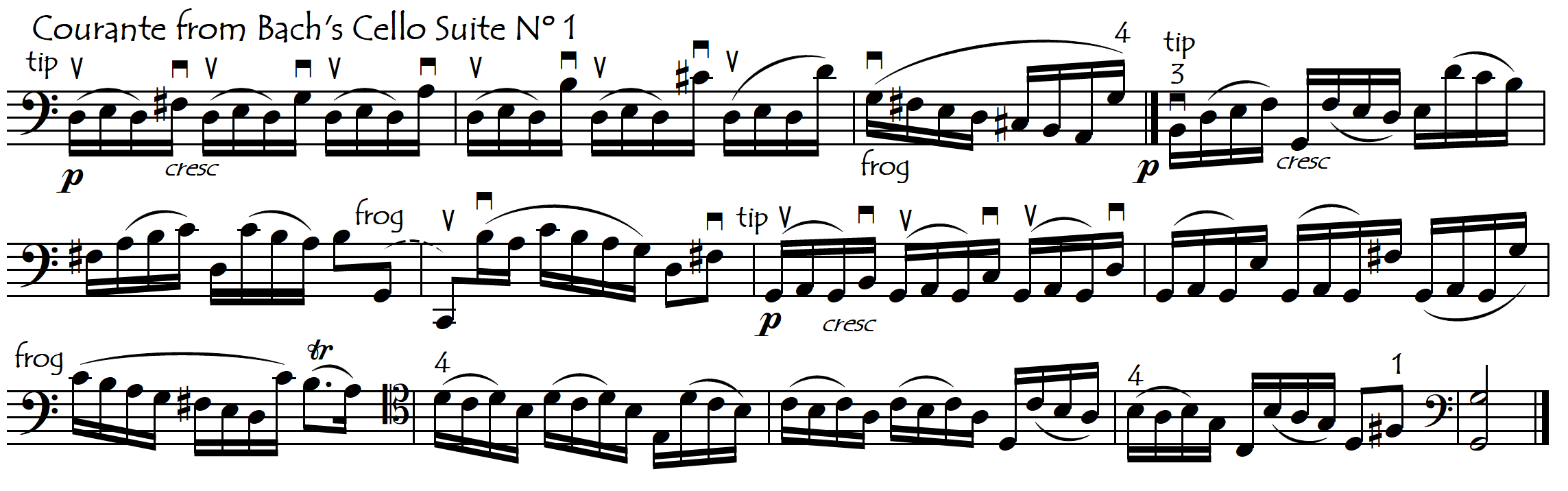

Sometimes, we are lucky and our asymmetrical, unbalanced figures combine in such a way that the passage “plays itself” without us needing to do any complicated planning or bowing tricks. The Courante of Bach’s First Cello Suite is full of these types of happy coincidences:

At the bottom of this page there is a link to a compilation of passages from the repertoire that exhibit this happy phenomenon. We will look at these later in more detail, but first, let’s take a look at those very frequent situations in which we are not so lucky and the complex passages do not “play themselves”.

SOLVING BOW-DIVISION PROBLEMS: MATHS AND ENGINEERING IN OUR CHOICE OF BOWINGS

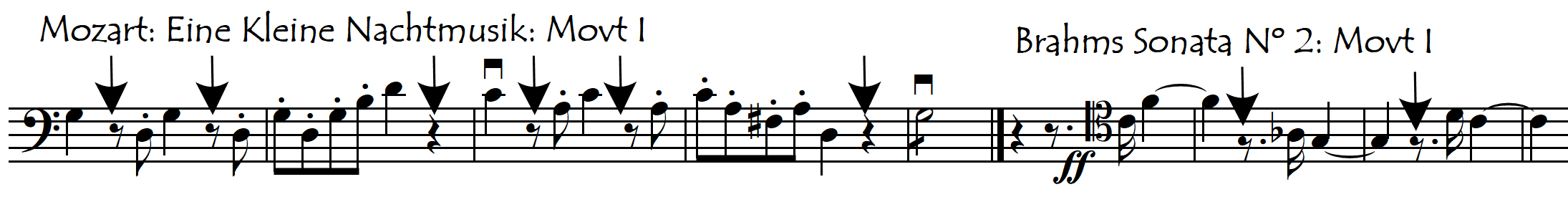

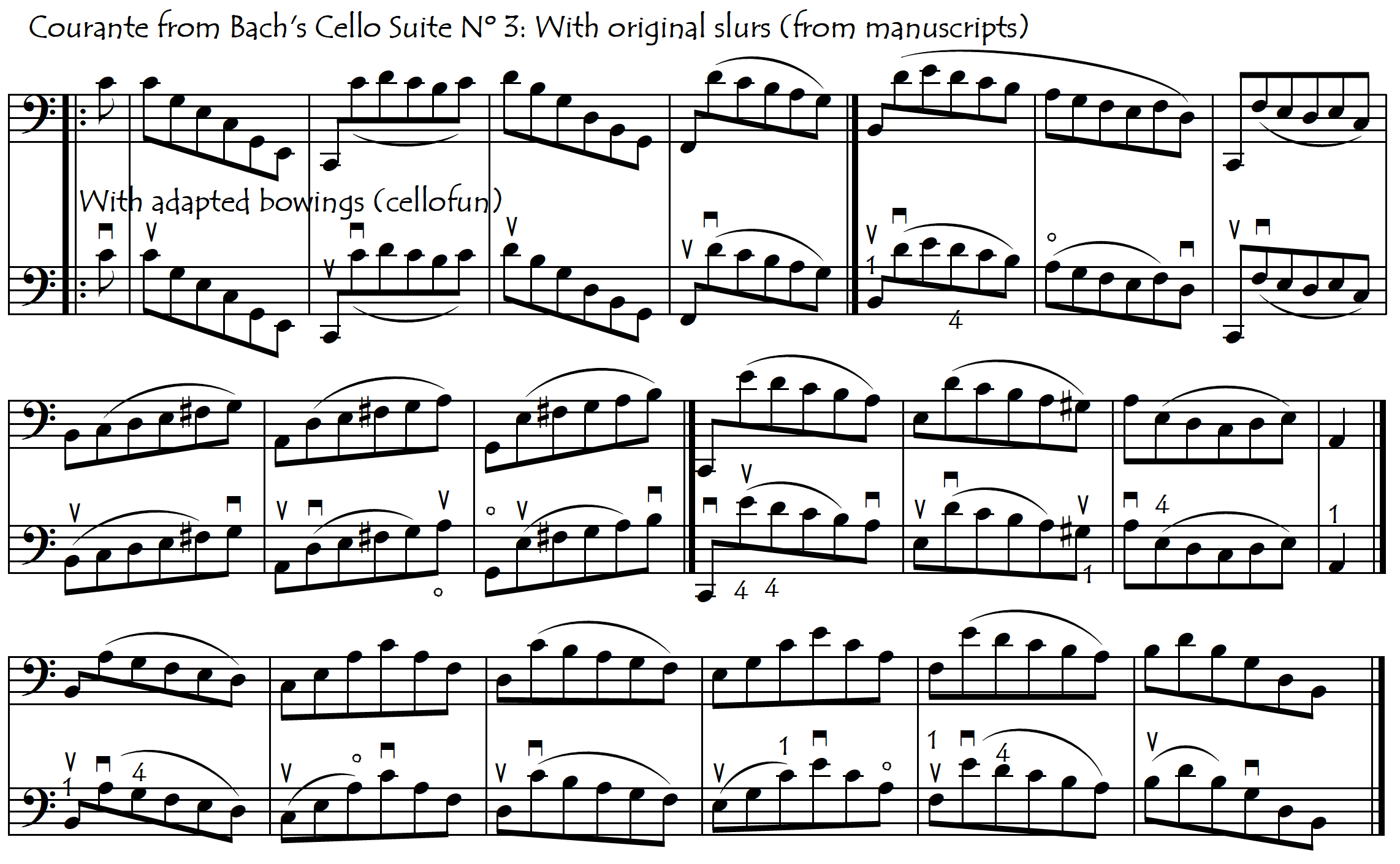

Very often, our asymmetrical, unbalanced passages, instead of “playing themselves” will tend to trip us over, tying us in knots if we try and play them with simple “as-it-comes” bowings. The Courante from Bach’s Third Cello Suite, if played with the original manuscript slurs, presents numerous examples of these types of passage, posing some serious problems of bow-division and therefore requiring some serious forward planning:

In order to avoid this very common problem, we have several possible bowing-choice tools (tricks) at our disposition: the retake, playing several notes consecutive notes in the same bow direction (as in hooked, portato or flying spiccato bowings), changing the slurs, or doing none of these “tricks” and simply getting around the problem by using enormous athletic skill and agility (= sleight of hand). Let’s look now at these different possibilities:

1: THE RETAKE AS A SOLUTION TO BOW-DIVISION PROBLEMS

If we can lift our bow off the string before or after the short note, then this enables us to move our bow, silently in the air, back to where we want it to be. This, along with “hooked bowings” (see below) is one of the easiest ways to solve the problems of bow division posed by repeated dotted figures.

The subject of “retakes” is a large one and has its own dedicated page:

2: HOOKED (OR PORTATO) BOWINGS AS A SOLUTION TO BOW-DIVISION PROBLEMS

In those unbalanced figures in which the musical articulation does not give us enough time to lift our bow off the string and “retake” it, we can avoid the bunnyhop accents (see below) by using “hooked” bowings. Here, we “hook in” the little note in the same bow direction as the previous longer note, with a separation between the two impulses (bow strokes).

The hooked bowings in the above example could be played with every degree of separation, from very separate to a throbbing, barely separated portato. This is why hooked and portato bowings are treated together, on their own dedicated page:

The hook/portato is an alternative to the retake. Here below are three repertoire examples that can be bowed with either retakes or hooked bowings to solve the problems of unbalanced bow division:

Fritz Kreisler’s “Liebesleid” is a wonderful piece to use for practicing and exploring hooked bowings in dotted rhythmic figures.

We need to be careful, when bowing unbalanced figures, not to eviscerate fiery music by making it too balanced and smooth with all the hooked and portato consecutive bowstrokes. Often, the roughness and energy that comes from the bow-speed imbalances are an important part of the music’s character. In the following example bars 2 and 3 need the energy of the “as-it-comes” bowings while bar 4 probably benefits from the hooked bowing :

3: FLYING SPICCATO AS A SOLUTION TO BOW-DIVISION PROBLEMS

If our “short notes” are spiccato then we might play them all in the same bow direction, in a brief “flying spiccato”. As this is a sort of fast portato, these bowings are also looked at in the article dedicated to hooked and portato bowings:

4: CHANGING (REWRITING) THE SLURS AS A SOLUTION TO BOW-DIVISION PROBLEMS

We can’t rewrite a composer’s dotted (or otherwise unbalanced) rhythms, but sometimes the asymmetries we must solve are simply questions of note groupings (slurs) rather than untouchable rhythms. Changing the note groupings (slurs) is a much lighter, less aggressive intervention and often very slight changes to the slurs can make a passage suddenly balanced in terms of bowspeed. We return to the example of the Courante from Bach’s Third Suite, but now showing in the lower stave some possible bowing solutions to eliminate the discomfort of the asymmetries in the original bowings:

SLEIGHT OF HAND: UNBALANCED FIGURES THAT CAN’T BE HOOKED, FLOWN, RETAKEN OR CHANGED:

Unfortunately, not all asymmetrical figures are suitable for retakes, hooked, portato and flying bowings, or rewriting of the articulations (slurs). Retakes require “air-time” to get the bow back towards the frog while hooked and portato bowings require that we have sufficient time to relax the bow pressure (and speed?) on the long note in order to be able to “restart” the bow in the same direction on the short note. Hooking-in a little note requires less time than a retake but if we can’t steal this time from the previous note then, above a certain speed, hooking also becomes impossible, as in the second bar of the following example.

S0, sometimes we can do neither a retake or a hook to solve the bowdivision problem of an unbalanced figure. And sometimes we really can’t allow ourselves the liberty to change the slurs because they form a vital element of the music, perhaps repeating throughout the piece and/or in other instruments. In these “difficult” cases, there are two possible (but not obligatory/unavoidable) negative outcomes for these unbalanced figures:

- an accent is caused on the little note(s) due to the fact that we need to use a suddenly much faster bow on it/them in order to get back to the end of the bow for the start of the next long note, or

- if we try to play the passage without accents on the short notes, our bow finds itself gradually working its way more and more to one end, which is why we could consider these bowings as “unsustainable”.

The back legs of rabbits are much more powerful than their front legs. This is why their running rhythm resembles more a dotted rhythm than the regular binary flow of other animals whose front and back legs are symmetrical. Playing dotted rhythms with hooked bowings (or retakes) is a way to avoid sounding like a panicked rabbit because these bowings eliminate the possibility of unwanted “bunnyhop accents” being given to the short notes by the sudden fast bow stroke. See also the page dedicated to dotted rhythms.

In the examples shown below, even though the bow is playing dotted rhythms (as shown in the second line), the “music” is not “dotted”: the notes flow uninterruptedly. Because of this, the “hooked” bowings that can make our life so much easier when playing dotted rhythms are much less appropriate here: we just don’t have time to stop and restart the bow (nor of course to retake it). So what then can we do in the following repertoire examples to avoid the bunnyhop?

In these cases, we need to make a choice between:

- finding the best bowing with which to play the articulation as written. Even with absolutely the best choice of bow directions, we may still be required to be a little like a magician, using radical bowspeed (and pressure) changes to avoid the bow being taken to where the laws of physics want it to go rather than where we want it to be, but at the same time making those radical changes as imperceptible as possible to the listener

- changing the slurs (articulations), while trying as much as possible to maintain the composers desired intentions

Our choice will depend on our answers to the following questions:

- does the composer understand string bowings and deliberately want to obtain the special “bunnyhop effect” (agogic accent) of the huge and sudden variations in bow speeds? In this case, we might not change the articulation.

- or, is the composer unaware that the articulation they are asking for, while perfectly uncomplicated for non-bowed instruments, is very awkward for a string instrument? In this case, we could change it to something that sounds better, rather than sounding bad with the composer’s original suggestion.

Certainly, when transcribing music from other non-bowed instruments we have every reason to change the slurs to make the most asymmetric articulations more “bow-friendly” because it is only for bowed instruments that these asymmetrical articulations pose a problem. The following passage is originally for flute:

Often the “reverse bowing” (upbow on the beat, and short note on a down bow) is more comfortable (as in the above example). This is especially so when the short note is on the higher string (as above) because the string crossing is greatly facilitated by going in the “right” direction (see String Crossings). But even if the short notes were to be on the lower string this “reverse bowing” still has many mechanical advantages.

Here below is a link to a compilation of rhythmically unbalanced repertoire excerpts for which neither the retake nor the hook can be used to alleviate the problems of bowdivision:

Unbalanced and Unavoidable Bowdivision Problems: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

HALLELUJAH !!: WHEN “AS IT COMES” BOWINGS ARE THE SOLUTION RATHER THAN THE PROBLEM

“As it comes”, with respect to bowings, means simply alternating up and downbows with no fancy retakes, hooks or portatos. Sometimes we are lucky, and the asymmetries in a passage counterbalance each other in such a way that we can use “as it comes” bowings without the bow being inexorably pulled to a place where we don’t want it to be. In these (lucky, fortunate) cases, we can consider that the bowings “play themselves”. At the top of this page, we used the example of the Courante from Bach’s First Suite to show several passages which, in spite of great asymmetry, actually play themselves without the need for any particular action on our part. Let’s look now in more detail at some of these passages from this Courante, for example:

This is like a very simple maths problem: we add up the beats going in one direction and then add up the beats going in the other direction, and then compare the two totals. For example, in the first four bars of the above example, even though the figures are all very asymmetrical, we play 7 semiquavers going out towards the tip and 5 towards the frog in each bar. This is quite balanced and the small difference is easy to compensate for with a minimal bowspeed correction, especially when, as in the above example, our need for a faster bowspeed corresponds with a crescendo and takes us towards the frog.

Bringing the bow “to where we want it” often means doing a crescendo towards the frog and a diminuendo towards the tip. In an ideal situation, bowing the asymmetrical figures “as it comes” does exactly that. If the phrase is in crescendo then we will bow it in such a way that the asymmetries take us from the tip towards the frog as in the following example from the same Bach Courante. If the phrase was to be in diminuendo, we could bow it in the opposite way:

Here are some more examples of this same phenomenon:

The following link opens up a compilation of repertoire examples in which we find ourselves in this happy situation:

Unbalanced Bowdivisions Which Play Themselves With “As-It-Comes” Bowings: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS