Sing-Speak ? Rubato and Rhetoric in Musical Interpretation

When we think of “music” we think usually of singing melodies. But music does not only sing. It also very often “talks”, and also even shouts, whispers, screams, sighs, pleads, laughs, cries and generally mimics all types of human (and animal) communication including body language. We can call these declamatory, dramatic (or spoken/conversational) aspects of music, rhetoric. An effective, powerful rhetorical delivery comes partly from the choices of Articulations and Phrasing/Dynamics but it is also – and perhaps principally – a question of timing (rubato and rhythmic micro-freedom in general). Perhaps we could consider “rubato” as the rhythmic freedom we use in a singing phrase, and “rhetoric” as the rhythmic freedom we use in a more declamatory (or theatrical) style of phrase/music ?

Playwrights and screenwriters do not indicate many expressive devices in their written dialogues. There are no indications of tempi, dynamics, phrasing, articulation etc. This gives actors enormous freedom to use their imagination to deliver the text (speak their lines) in the way they consider most effective. In classical music, on the other hand, composers normally notate the rhythms, articulations, tempo changes and dynamics of the sounds (notes) as exactly as possible. These indications can help us, but should not discourage us from adding more of our own expressive (rhetorical) details.

Musical notation is necessary to transmit a composer’s ideas, but the fact that rhythmic notation is so precise shouldn’t mean that we are not allowed to play with our own commas, pauses and small variations in tempo, as well as being free to add our own additional phrasing, articulations and dynamics that are not specifically indicated in the written score. This is “performance rhetoric”: the art of how to present a certain defined content in a more effective, communicative way. In other words, the art of how to make what we are saying (playing), more meaningful and more powerful.

The opposite of rhetoric is robotic. Imagine an actor reading a text metronomically, without taking any of these subtle, dramatic “rhetorical” liberties. It would be like a child, reading aloud, but not really understanding what they are reading. Very often we musicians are guilty of this type of rhythmically-robotic delivery. This is understandable: not only are we trained to play “exactly what’s on the page” but also, playing without rubato or rhetoric makes fitting together the different instruments/voices of an ensemble definitely a much easier task.

Operatic music is usually played much more freely than instrumental music: the acting and the words/lyrics certainly encourage this dramatic delivery. Unfortunately however, in instrumental music performance, we are often so frightened at the thought of offending critics, purists, teachers and academics, that we don’t dare to add these little personal, dramatic touches to the score, which then becomes like a prison (see Freedom or Obedience?). This is a great shame.

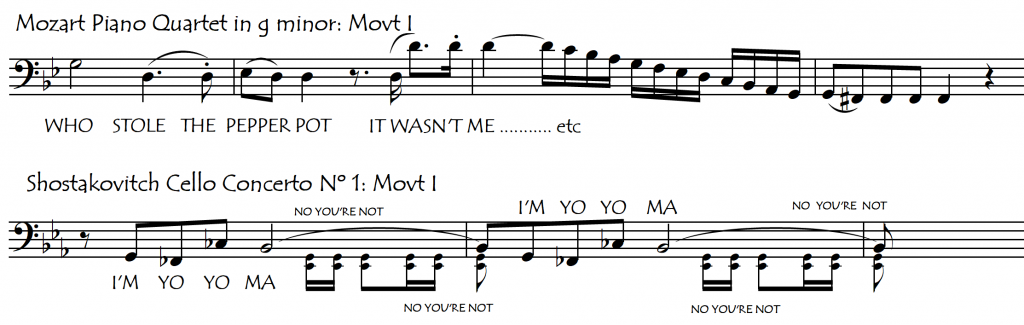

Putting words to our musical phrases can often help us to feel freer and to give more meaning to our music, as though we were singing a song or acting a part. Sometimes the “right” words for a phrase might be deep and meaningful. Other word choices might just have the effect of loosening us up with some comic relief:

Bach‘s Solo Suites (and Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas transcribed for cello) are an excellent starting point for an exploration of (serious) rhetoric in music. They have very few singing melodies, no expressive indications and as we are unaccompanied, we are thus free to not just “sing” them but also to “talk, recite and declaim” them, exactly as we wish. In the Cello Suites, this idea is especially relevant in the Preludes, but also (to a slightly lesser extent) in the slower, freer dances (Allemandes and Sarabandes). But also, even many of the faster movements need a lot of these “rhythmic micro freedoms” (in addition to loads of phrasing, dynamics and articulations) in order to avoid them sounding like minimalist sewing machine music. In Bach’s B minor Partita for Solo Violin, for example, five of the eight movements run a serious risk of sounding like the dreaded sewing machine because of the uninterrupted flow of equal note values, as shown in the following table:

|

SEWING MACHINE RHYTHMS IN BACH B MINOR PARTITA FOR SOLO VIOLIN |

||

|

MOVEMENT |

TOTAL NUMBER OF NOTES |

NUMBER OF NOTES OF EQUAL RHYTHMIC VALUE |

|

Double I |

380 |

378 (semiquavers/16th notes) |

|

Courante |

476 |

474 (quavers/8th notes) |

|

Double II |

956 |

953 (semiquavers) |

|

Double III |

300 |

298 (quavers) |

|

Double IV |

532 |

531 (quavers) |

The unwillingness to take (or fear of) rhythmic liberties is probably what leads so many people to play this music very fast. At least that way, the effect of the high-speed virtuosity makes up somewhat for the lack of the performer’s micro-rhythmic courage (or interest).

ENCOURAGING MICRO-FREEDOMS: MEMORISATION AND A VERY SLOW METRONOME PULSE

One good way to develop rhythmic micro-freedom is to play with the metronome beats very far apart. This has nothing to do with the speed of the music, but just means that instead of having the metronome beating each quarter-note (crotchet), we might have it beating each half-note (minim), or each bar, or every two bars etc. No matter how fast or slow the music is, we can always choose a slow pulse speed for the metronome. This allows us to take rhetorical micro-liberties with the rhythm while still maintaining a steady basic pulse for the music. This is a very useful skill (see the article by Gary Karr from The Strad issue xxx), but unfortunately, most metronomes don’t go slowly enough! The mania for mathematical rhythmic accuracy is such that any metronome will subdivide up to a very high number of beats per minute but won’t go slower than 40/minute which is absolutely the opposite of what we need.

Playing from memory is another good way to liberate ourselves from the “tyranny of the written notation” as we will soon forget what was written, and start playing with spontaneity, personality …………….. and rhetoric (dramatic musicality).

RUBATO/RHETORIC IN MUSIC OF THE CLASSICAL PERIOD

In music of the Romantic Period, rubatos come very naturally and are often quite extreme (large, pronounced). In music of the Classical Period however, rubato/rhetoric is a much more subtle affair. Because of this, the use of rhythmic freedom/rubato/rhetoric in music of this period tends to be considered by interpreters as a danger-zone which many interpreters prefer to avoid, choosing to err on the side of the metronome rather than risk being accused of excessive liberty. The definition of taking “too much” liberty with the rhythms is when our freedoms take us into the world of bad taste, but somewhere in between these opposite extremes of an extravagantly “un-classical”, kitsch, romanticised performance and a robotic, metronomic delivery lies a degree of micro-freedom that creates magic.

Many wonderful examples of this magical use of micro-rhythmic freedoms can be found in the recordings of Walter Klien playing Mozart (and Haydn) Piano Sonatas, and of the Mosaic Quartet playing Haydn’s Opus 2o string quartets.

A tiny wait before a note, a tiny (and brief) tempo change: often the metronomic deviations are almost imperceptible but create a type of magic in which the classical perfection becomes also suddenly imbued with huge additional emotional and philosophical meaning. It is no wonder that the Tokyo Quartet was particularly famous for its interpretations of music of the Classical Period as this music benefits so much from the careful attention to the minutest details that we so associate with Japanese art, culture and society.

CADENZAS, UNACCOMPANIED PASSAGES AND MUSICAL DICTATION

In cadenzas we are absolutely on our own and can suddenly do exactly as we want in terms of rhythm, free from any risk of losing our fellow musicians. The opening interventions of the cello in both the Brahms Double and the Lalo Concertos are good examples of this situation. Very often, when the accompaniment stops, it is an invitation (or even a request) for the solo musician to take freedom with the rhythm and tempo. In any other ensemble passages however, our rubatos need to be able to be understood by the other musicians. Perhaps the best description of this need was given by the conductor Adrian Boult who, when unintelligible rubatos were being made in his orchestras, would say “Gentlemen, I have to be able to take it down in dictation”.