1A: MUSIC NOTATED IN ONE KEY BUT SOUNDING IN ANOTHER. KEY SIGNATURE: HELP OR HINDRANCE ?

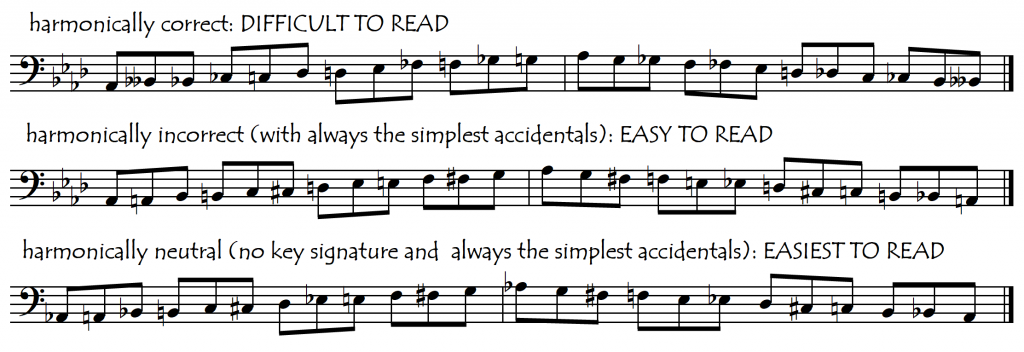

When composers write music that sounds simultaneously in two (or more) different keys, this is called “polytonality” and can be a problem for the listener’s ears. But when composers notate their music in a different key signature to how it sounds, there is absolutely no problem for the listener’s ears, but there can be serious problems for the players’ brains because although the music sounds tonal, it can be hard – or very hard – to read, depending on how far apart the two keys are. When the music modulates into different keys, composers will often just pile on the accidentals, including nasty double-sharps and double-flats for harmonic accuracy, rather than changing the key signature in the score. The reading difficulties derived from this situation are unnecessary stress-producers and if we were to invent a name for this phenomenon it would not be complimentary!

We instrumentalists are usually not highly trained in harmony and our principal priority is to make beautiful music rather than to be intellectual music-reading virtuosi. This problem is especially significant in orchestral playing where we need to play large amounts of notes with little rehearsal time. All the concentration that is needed to decipher unnecessarily difficult reading problems consumes brainpower that is no longer available for making music, listening, and following the conductor. It would make learning a piece so much easier to have the notes written out in the simplest possible way, which usually means in the most appropriate (simple) key signature. Easier reading = easier learning = less brain-strain. Here below are a few more examples:

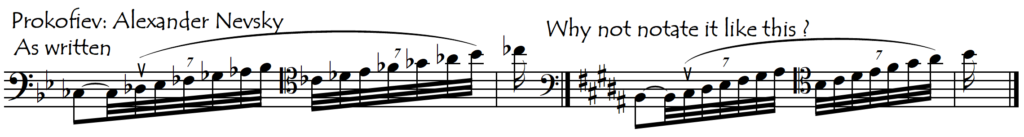

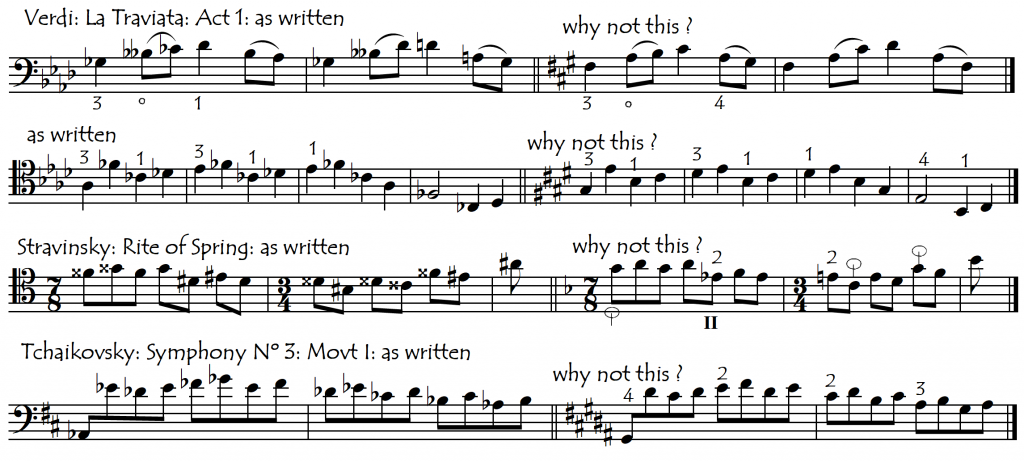

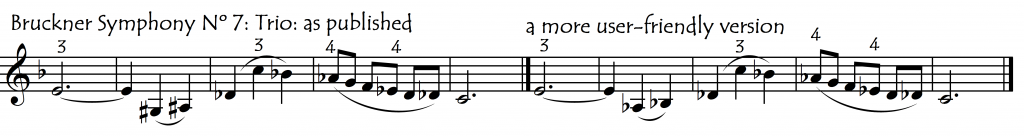

In the above examples, all the accidentals in each passage were either sharps or flats. When composers mix flats and sharps in the same passage it’s as though they were using two languages in the same sentence (or two keys in the same phrase). This also creates unnecessary reading problems.

There are times, however, especially in highly chromatic passages, when mixing flats and sharps can help us with our reading, so long as the choice of flat or sharp follows the rule of “always using the simplest notation”. This works best when there is no key signature (C major).

Here are some more repertoire examples of “user-unfriendly” pitch notations due to the use of unnecessarily complicated (although harmonically “correct”) accidentals. Once again, by changing (or eliminating) the key signature we allow the use of simpler accidentals:

We could compile an entire encyclopedia of examples of these user-unfriendly notations, with their “simpler notation” alternatives, but we will make do with two pages of examples here:

User-Unfriendly Pitch Notations: REPERTOIRE EXAMPLES

In this type of repertoire (normally late-romantic and 20th-century), the harmonic complexity, and the frequency (and extremity) of the modulations often mean that the notated key signature can at times not only be irrelevant but can even be a serious obstruction to fluid reading. As mentioned above, if the composer does not change the key in which the music is notated then they are obliged to use many accidentals, and often strange ones like double sharps and double flats which greatly complicate our reading task. In these cases, there could be considerable advantages for the players’ music reading – especially for sightreading – if the music was simply notated without any key signature. Bartok actually followed this principle in most of his music.

If the key signature were to be left “empty” (C major/A minor) the player would benefit from the following advantages:

- all required sharps or flats (“accidentals”) would be attached to (printed with) the notes that they affect so we no longer need to always remember the key signature.

- all accidentals could be of the simplest types, using always the easiest-to-read version of a note with no need for double sharps or double flats

Of course, in music that stays in (or near to) its notated key, the key signature is a help, removing a lot of clutter from the part, but it was usually mainly a help for the traditional music printer and copyist. By reducing the number of characters that needed to be placed in the score, it reduced their workload. Nowadays with all music typesetting being done on computers, this factor is no longer relevant and more consideration could be given to the player’s ease in reading.

ACCIDENTALS SHOWN ONLY ONCE PER BAR

The fact that an accidental is only shown once per bar (measure) means that in music that is very chromatic, harmonically complex (and/or when the bars have a lot of notes in them), the player has to have a very good memory for the notes that have just been played in that bar, but only in that bar (and not before). This is an unnecessary added difficulty frequently found in late-romantic and modern classical music. Music notation was not always like that: Bach notated every accidental always, which is extremely helpful as his music is often very harmonically complex. In the sheet music offered on this website, we have normally reverted to this “user-friendly” tradition.

1B: PLAYING MUSIC IN “STRANGE” KEYS

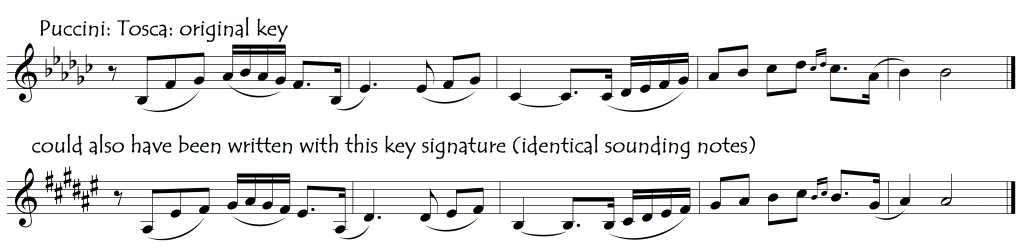

Key signatures are a little like politics. The further away they get from the centre (C major/A minor) the more they look different on paper ……. but the more similar they actually become! A passage written in an extremely flat key could be just as easily written in an extremely sharp key, as illustrated by the following passage from Puccini’s “Tosca”, written in Gb major (with 6 flats) but which could equally well (and simply) have been written with exactly the same sounding pitches in F# major (with 6 sharps):

We are normally not very used to playing music in “strange” keys. We can define these “strange keys” as being those with four (or more) sharps or flats. When we do suddenly find ourselves in these exotic keys we can often struggle with the reading, especially when there are accidentals piled on top of the already-strange notes. Fortunately, this is a simple problem to solve: we just need to practice/play more often in these distant keys.

But what material can we use for this ? There are many studies (Duport Nos. 12, 17, 18, 19 and 21. Popper High School Op 73 Nos 3, 4, 30, 35, 37 and 39 etc) that use exotic keys, but these are mostly not very useful for two main reasons:

- because they usually include a lot of other significant technical difficulties which occupy our concentration much more than the simple key/note reading difficulties

- they often go up into the high registers a lot which is not where we need practice in reading and playing in these strange keys. Up high, there are no open strings and it doesn’t really matter in which key we are playing: everything is transposable as the thumb is now our open string equivalent. We mostly need to practice our exotic keys in the Neck and Intermediate regions.

For the moment then, probably the best material is repertoire passages. Here below, can be found suggestions for (or links to) substantial (long) repertoire passages in a selection of keys that have four or more sharps or flats in their key signatures. Passages that modulate wildly and wander far from their key signatures are not included.

FOUR FLATS:

Ab major: Telemann Fantasia Nº 7

F minor: Beethoven Quartet Op 96, Brahms Cello Sonata Nº 2 Movt III,

FOUR SHARPS

E major:

C# minor:

FIVE FLATS

Db major: Tchaikovsky Symphony Nº 4, Movt I

Bb minor: Brahms Sonata Nº 2 Movt IV

FIVE SHARPS

B major: Brahms Piano Trio Op 8 in B major

G# minor:

SIX FLATS

Gb major:

Eb minor:

SIX SHARPS

F# major: Brahms Cello Sonata Nº 2: Movt II (Adagio)

D# minor:

SEVEN FLATS

Cb major:

Ab minor:

SEVEN SHARPS

C# major

A# minor

**********************************************************

In the above section, we looked at reading problems derived from the use of accidentals. Now let’s look at some other types of pitch-reading problems:

2: WHERE THE WRITTEN NOTES SOUND AT A DIFFERENT PITCH (Scordaturas )

There are two standard situations in which the notes that sound are not the notes that are written:

2A. SCORDATURA OF EXISTING STRING(S)

“Scordatura” is the italian word for “de-tuning” (or dis-tuning). It refers to those situations in which we are required to retune one or more of our open strings to a different pitch to the standard A, D, G, C tunings. The best-known works that use scordatura tunings are Bach’s Fifth Suite for Unaccompanied Cello (with the “A”-string tuned down to a “G”) and Kodaly’s Unaccompanied Cello Sonata (with both the two lower strings tuned down a semitone). Our transcription of Telemann’s Fantasia Nº 7 for Unaccompanied Violin also makes use of scordatura (C-string tuned down a semitone) because there seemed to be no other key in which this piece could be as comfortably played.

If the notes on the de-tuned strings were to be notated at the correct sounding pitch then we would need to dedicate an enormous amount of brainpower to calculating which fingers we would need on the de-tuned strings and it is simply not worth it for anything but the simplest (and slowest) music. It is easier in these circumstances for the brain to “play by numbers (actually fingers)” rather than to play “by pitch”. If, as is standard practice, the notes are notated according to the finger and string that we need to use rather than according to the sounding pitch, then we have no reading problems at all. But we can easily have memorisation problems because our brain (and fingers) “know” that something is not right ! (see Playing From Memory).

2B. ADDITION OF AN EXTRA (HIGHER) STRING: THE FIVE-STRING CELLO

When playing a 5-string cello, it may be easier for our brains to have our music notated one fifth lower than it actually sounds. That way we can play it as if our top (E) string was simply an A string. Although the music will sound a fifth higher than written, this way of writing/reading makes life easier for us in two ways:

- it eliminates most of the reading problems as usually, these high pieces, make much greater use of the new high string than they do of the C string. In other words, there are usually many fewer notes on the C string than on the E string in these pieces. It is easier to learn to read a few notes below the C string than hundreds of notes on the E string.

- it eliminates the problem of knowing on which string we are playing (for both the bow and the left hand). This is because our positional sense for both hands is extremely relative: any one string serves as the positional reference from which we find the other strings. When the top (“A”) string suddenly becomes the second (“D”) string – and likewise for all the other strings – we can rapidly get completely lost with both hands. If, by contrast, we just pretend that the top string is always the A string, we avoid this problem.

Writing the music out one fifth lower for a 5-string cello follows exactly the same principle that we use in “scordatura” notation. In “scordatura” we write the note that corresponds to the finger we want to use rather than to the pitch it will actually sound. We do this in order not to confuse our brain. Here, instead of deluding the brain only about the pitch our finger is playing, we are now deluding it about both the pitch and which string our bow is on. It’s a little like a “double white lie” and while it may seem like “cheating”, it certainly saves our brain an awful lot of work.

3: CLEF CHAOS

A third frequent source of pitch-reading problems comes from the sub-optimal use of clefs. We cellists are unusual in that we are accustomed to reading music in three clefs. This is more than most other musicians. It is easy to understand that composers have more important things to think about than their choice of clefs for the cello line in their full score, but editors – who produce the playing parts – could often do a better job in choosing the clefs that are used in any given passage. Reading notes high above the stave is something that we – unlike violinists and pianists – are not used to, and it is so easy to bring the notes down into an easily readable range by using the treble (or tenor) clef. Counting ledger lines is a totally unnecessary difficulty and in some pieces, written out way above the stave, this problem may even justify rewriting the passage in a more appropriate clef (or just memorising it).

Some instruments sound one octave different to the way their music is notated: double-basses, classical guitars and tenor voices sound one octave lower, and flutes one octave higher than what we would expect from a literal reading of their clef. While this is absolutely standard procedure for those instruments it is not at all standard for cello music. Occasionally however we cellists are confronted with music written out in the treble clef, but which needs to be sound one octave lower than actually written. This was standard practice in the 18th century and although it gradually tended to disappear even some 19th and 20th-century editions continue(d) to use it. Reading in the treble clef and simultaneously transposing down one octave is not easy, especially in sight-reading or faster music.

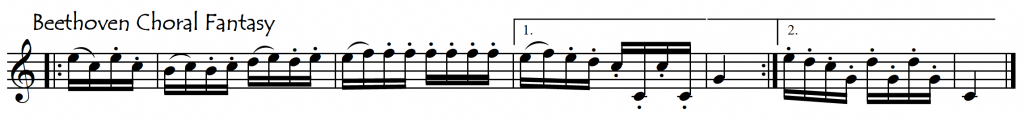

This notation is a totally unnecessary complication that confuses us and can take us by surprise. It occurs very often in Dvorak’s orchestral music but is also quite common in the music of the Classical Period: Stamitz and Breval systematically wrote the cello’s higher passages in the treble clef, but with the intention that the music would sound one octave lower. This practice was not however solely confined to the lesser editions of works of minor composers: it is found also in standard editions of music by Beethoven and Haydn, among others. A very trusting (and un-forewarned) principal cello of an orchestra might have an unnecessary rise in stress levels on seeing the following solo passage from Beethoven’s “Choral Fantasy”: although notated in the stratosphere, it is actually played one octave lower. We can only ask ourselves why Beethoven wrote it like that, and why editors have not the courage to change it ?? (see the article about Urtext).

In an urtext edition of Stamitz’s A major cello concerto, the solo cello part is also notated almost entirely in the same way. This really is taking the concept of “Urtext” to an absurd, impractical level.

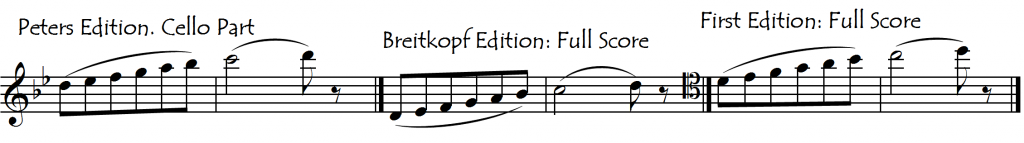

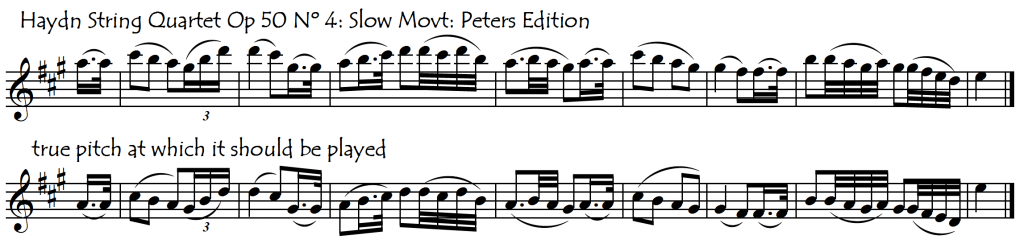

All of the clef-reading problems that we have discussed above can be seen combined in the following passage from the slow movement of Haydn’s Quartet Op 50 Nº 5. Here, depending on the edition that we consult, we might find several different uses of clefs and/or an octave transposition for the following phrase eight bars from the end. In the first example, we need to play one octave lower than written. In the second and third examples the pitch is “as-written” but only in the second example is a “user-friendly” clef chosen.

Normally, clefs are chosen in order to keep the written music as close to the stave as possible. When cello music is written out one octave higher than it is actually played and also lies way above the stave, then these two unnecessary complications combine to produce a music-reading nightmare!!

Occasionally, we are instructed to play passages, written in the bass and tenor clefs, up an octave. This, once again, is an unnecessary obstacle to fluid reading. In the fourth movement of the Novello edition of the Elgar Concerto, before rehearsal Nº 66 we have 9 bars written out in the tenor clef, with the instruction to be played one octave higher. It’s tricky to read this, but it is even more difficult to understand why anybody who knows of the existence of the treble clef would think to use this type of notation. As with all sub-optimal clef use, the only good thing we can say about this is that the brain activity that it requires might have the collateral benefits of warding off Alzheimer’s disease?!