Tremolo For String Players

The word “tremolo” comes from the italian verb “tremere” which means to tremble/shiver/shake. Like pizzicato, it is a technique (musical effect) that is rarely used in solo music but it is very commonly used in orchestral music, most especially in opera and in music of the Romantic Period and later.

TREMOLO SPEED

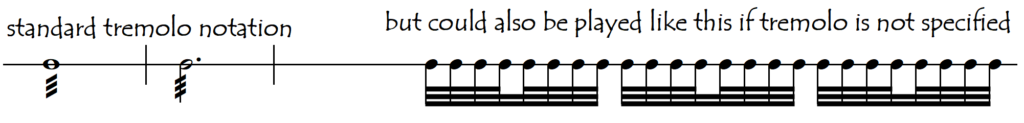

By definition, tremolo uses an undefined speed of bow direction alternations which must not be a subdivision of the basic pulse. If composers want a regular, subdivided, rhythmical effect, they can indicate this with a calculated number of crossbars on the stem of a long note. Unfortunately, a stack of crossbars on the stem of a long note is also the standard notation for tremolo which means that if the composer doesn’t actually write “tremolo” (or “trem”) over the note/passage, there can be, in slower tempi, a certain ambiguity (confusion) about their intentions.

The lack of definition of the tremolo speed gives us huge freedom to choose anything along the range between ultra-low speed and ultra-high speed oscillations. With tremolo, the frequency (speed) of the oscillations equates with the emotional intensity of the music: high-speed tremolos (at any dynamic) are very intense, electric and excited whereas low-speed tremolos are gentle, smooth, warm and relaxed. So the speed of our tremolos at the start of most of Bruckner’s symphonies will be very different to that of our tremolos in the multiple emotional crises of a Verdi opera.

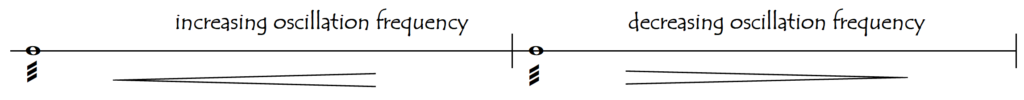

We can use variations of our tremolo speed (oscillation frequency) as an enhancer of dynamics, increasing the speed during a crescendo and reducing it during a diminuendo:

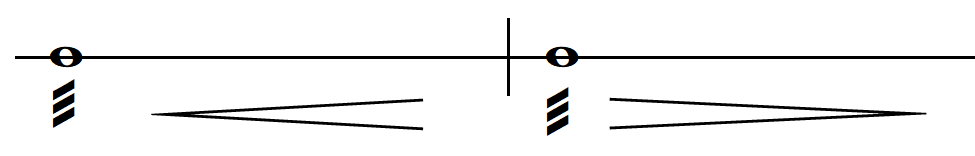

Following the same principle, a tremolo fp/sfz can start with a sudden burst of fast oscillations followed immediately by a much slower tremolo speed.

TREMOLO AS A TOOL TO IMPROVE OUR GENERAL PLAYING SKILLS

Tremolo is not only a musical special effect but is also (just like pizzicato) a very useful tool for working on certain aspects of our technique for both hands. A gentle, relaxed tremolo is an “easy” bowing that not only allows us to concentrate all of our attention on the left hand but also blurs the precise requirements of coordination between the hands. The blurred contours (edges, boundaries) of tremolo bowings encourage and facilitate the use of anticipation and preparation not just for left-hand shifting but also for right-hand string crossings.

Tremolo is also a revealing diagnostic tool for our right hand and arm because its successful execution requires a loose, flexible interaction between the arm, hand, wrist and fingers. In tremolo, we basically “shake” our hand from side to side, as though we were mixing a cocktail, but now on a horizontal axis. Just like with all other deliberate shaking movements, we need to involve the entire arm and every joint, from the fingertips to the shoulder, in order to achieve an ergonomic, comfortable relaxed sustainable movement that won’t seize up nor give us tendinitis when (as is often the case in large orchestral works) we need to maintain it for long periods. Curiously, it can be advantageous to include some vertical wrist movement (wing flap) as a component of our tremolo, adding a little bit of circular wrist looping to the simple left/right oscillations.

We can also use tremolo to work on our control of the bow’s point of contact and on the relationship between bowpressure and bowspeed. Try to achieve the following dynamics, each time with only one of those three variables (point of contact, bow pressure and bow speed):

The fact that in tremolos we can stay in the same part of the bow, helps us to be able to focus our attention on each one of these isolated variables.

FROGS AND TREMOLO

Frogs don’t like tremolos, or to be more precise, tremolos don’t like being played at the frog. Tremolos are played mostly in the area from the middle to the upper half of the bow and the softer the tremolo, the closer to the tip of the bow we will probably want to play. For louder tremolos, we will move away from the tip but, even for the loudest tremolos, we will never be near the frog as it is impossible to play a loose, ergonomic tremolo in that part of the bow.

LONG-TERM SHOULDER CONSERVATION

Even though the tip of the bow might give beautiful, soft, shimmering tremolos, extended passages of tremolo played at the tip (especially on the higher cello/bass strings and the lower violin/viola strings) will be very tiring and ultimately unsustainable for the shoulder and arm if played out there. It is only for this ergonomic reason that we will probably play our long, soft tremolo passages nearer the middle of the bow.