Shifts Involving Open Strings and/or the Midstring Harmonic

USING THE OPEN STRING AS A SHIFT FACILITATOR

Very often we will use an open string to shift on (in other words, we will shift while we are playing an open string). This has the huge advantage of giving us extra time (the duration of the open string note) to get into the new position. But shifting on the open string also has some of its own unique difficulties, the most notable of which is the fact that we normally can’t do an audible glissando.

We can usefully subdivide “shifts on an open string” into two very different sub-categories:

- shifts on the same string as the open string

- shifts on a different string to the open string

These two shift types are very different. When we shift on the same string as the sounded open string, we automatically lose our finger/string contact during the shift because we need to release our fingers in order for the open string to be able to sound. This is why we can call these “Mid-Air Shifts” or simply “Air-Shifts”. When shifting during a different open string however, we can maintain our finger contact during the shift but we normally cannot hear our glissando which is why we could call these “Silent-Gliss Shifts”. Shifting without finger/string contact is considerably more difficult than shifting with this contact. Let’s look now at these two types of “shifts on the open string” in more detail:

1: SHIFTING ON THE SAME STRING AS THE OPEN STRING: “AIR-SHIFTS”

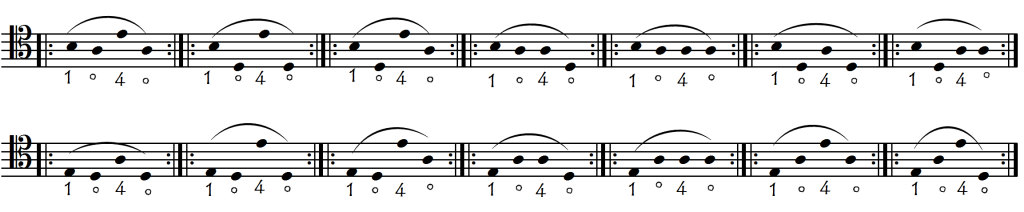

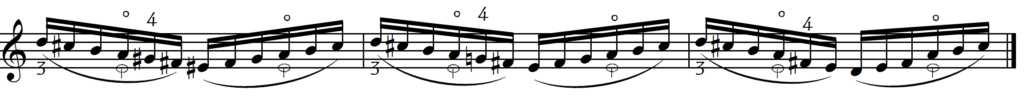

The following examples are to be played on the D string. Any of the fingers can be used on either of the stopped notes. In the progression from Ex 1 to Ex 4, we have progressively less time to do our hand displacement to the “C” (Do).

During the open string, we must obligatorily remove all fingers from the string in order for the open string to sound. Our left hand is at rest, but our right hand is still playing so, unlike in a “real” rest (in which we stop playing completely), no matter how long the open string lasts, it would be quite unusual for us to take our hand away from the fingerboard for a complete rest. Thus, while we lose our finger contact with the fingerboard during the open string, the contact of the thumb under the cello neck is normally maintained.

Because of this loss of finger contact, if we need to change position (shift) during the open string, we have no possibility of using a glissando (slide) unless we have another finger down on a different string (which is very unusual). We might think that the thumb maintains its contact behind the cello neck in order to help keep our bearings during the shift, but close observation reveals that it doesn’t. Therefore, hand displacements up and down the cello fingerboard done in this way (without the possibility of finger contact because of the open string), actually have a lot more in common with “Finding Notes From Midair” than with “Shifts“. But these findings of a new position after the same open string are actually more difficult than both of these other two ways of finding notes. Let’s look now at why this is.

The effect of having to remove the playing finger from the string (in order to be able to play the open string) is similar, but not identical, to the effect of a rest. Even though the music continues, it is only our right hand that is working: our left hand is at rest. In theory, being able to rest the hand is a good thing, but not in these circumstances because, during this rest (while the open string is sounding), the loss of finger contact with the fingerboard means that the hand is not only free, it is lost in space!! Not completely lost (that happens when we release the thumb contact also) but partially lost because we now only have half of the normal left-hand contact with the cello (i.e thumb contact but no finger contact).

In a “real” musical rest (a silence), the hand can be lost (at rest) without causing any problems because we have time to place the new finger in its new position, and even quietly check its pitch (see Left Hand Pizzicato) before we start to sound it with the bow. But this possibility does not exist here because, while the open string is sounding, we can only wait, with the finger poised over its future position but with no possibility for checking either its intonation or its perfect horizontal positioning (see Left Hand String Crossings). Placing the finger after the open string we have no second chances: the moment of finger placement is the moment it will sound, and our only opportunity to correct its placement is immediately after we hear it.

Compare this situation with that of a normal shift. In a normal shift, our glissando (audible or not) allows us to both assure our finger is perfectly placed on the string, and to measure the distance it is travelling. When shifting during the same open string we can do neither of these. Decidedly, finding a new position after the same open string is one the most difficult type of “note finding” that we will ever have to do and for this reason is often a source of bad intonation. Only finding notes “out of the blue” in thumbposition is harder.

To summarise: normally, slurred shifts on the same open string are more difficult than other forms of shifting/note-finding because we are deprived of both the glissando and of the possibility of preparatory finger placement. We say “normally” because while these shifts automatically start as “airshifts,” sometimes they don’t need to be airshifts for their entire duration. If we want a little portamento (audible glissando ) in the shift then there is no reason why we can’t put our finger down on the string a little before its arrival destination. This little trick actually eliminates the problems of positional insecurity inherent in airshifts because we now can correct the position of our hand both horizontally (stopping the string exactly in the best part of the fingerpad) and vertically (intonation) before the official start of the new note.

In those cases where a big juicy portamento might be inappropriate (ugly, kitsch, in bad taste), our preparatory portamento can be so small and so discreet that it is almost inaudible. Even when it is so small as to be almost unnoticeable it still makes a great difference to our intonation security to be able to slide up into the target note in this way

Here are some pages of practice material for working on the skill of shifting during the (same) open string:

Airshifts During Open String: TONAL EXERCISES (mixed extd and non-extd)

Chromatic Airshifts in Extended Position During Open String: EXERCISES IN NECK REGION

The above material stays exclusively in the Neck and Intermediate Regions because, without thumb contact with the cello as a positional reference, in thumbposition this technique is basically so insecure that it is very rarely used.

2: SHIFTING DURING AN OPEN STRING BUT ON (OR TO) A DIFFERENT STRING: “SILENT-GLISS” SHIFTS

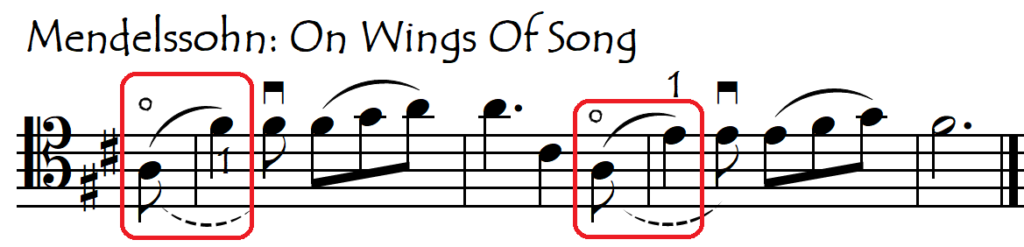

By contrast, when we use an open string to shift on or to a different string (as in the examples below), then the shift becomes considerably easier because we can now maintain finger contact with the new string throughout the shift.

Maintaining the finger/string contact during the shift gives us three significant advantages:

Maintaining the finger/string contact during the shift gives us three significant advantages:

- doing a shift with finger/string contact – audible or not – gives us a much more precise control of intonation than when we are “landing from mid-air”. With finger contact during the shift, we can dosify the audibility of the glissando according to both musical taste and technical necessity. For difficult shifts in which musical taste doesn’t want an audible slide, we will reduce the audibility of our glissando so that it is really only audible to the player. Even if we decide to do a completely silent shift (inaudible glissando), we can still practice the shift with a helpful audible glissando and then, in performance, just imagine it.

- the “horizontal” positioning of the finger pad on the string can be controlled and corrected constantly and instantly during the glissando.

- we don’t need to coordinate the placement of the new finger with the rhythm or the bow. We can place the new finger at any time we like before the bow starts playing on the new string.

This technique can often be used to great advantage in our fingering of fast passages because it gives us more time to shift.

It is especially useful when our bow string crossing to get to and from the open string is in the advantageous direction as in the above examples. If we play each of the above three examples with a slur on the first two notes, the string crossings to and from the open string will be in the unfavourable direction and we may find now that the bowing complication associated with the quick crossing to and from the open string might override (cancel out) the left-hand advantage of having more time to shift.

Here is some practice material for working on this area of our technique:

Silent-Glissando Shifts On One String During A Neighbouring Open String: EXERCISES

Silent-Glissando Shifts On One String During A Neighbouring Open String: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

SHIFTING AFTER A MIDSTRING HARMONIC: AIRSHIFTS OR ….. ?

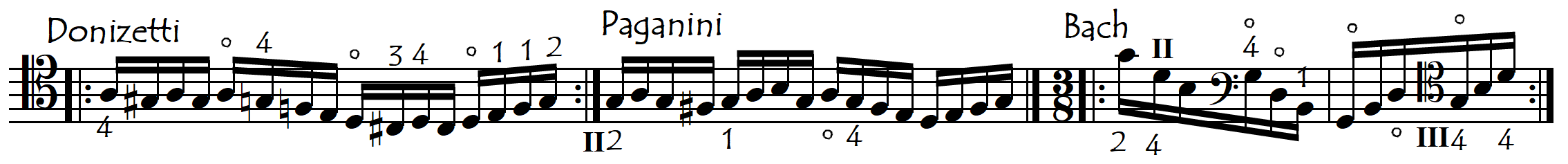

The midstring harmonics are – just like the open strings – great facilitators of shifting, and we will very often play the midstring octave note as a harmonic to facilitate shifting to or from it. Shifting to the harmonic is so much easier than shifting to the same note with the finger stopped, but also, shifting from the harmonic (most notably downward) is usually a lot easier than shifting from the same stopped note.

Shifting down after a midstring harmonic can be very similar to shifting during an open string. Just like with shifting during an open string, if our shift is on the same string, we can do an “airshift” after the harmonic because the harmonic, like the open string, doesn’t need the finger to be stopped in order to keep ringing.

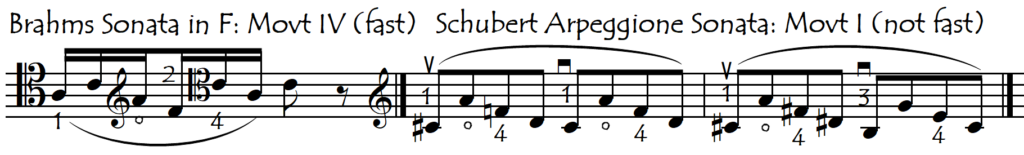

For shifts on the same string during an open string, the airshift is obligatory in order to allow the open string to sound. For shifts during the midstring harmonic, however, we can sometimes maintain finger contact with the string during the shift and thus have a portamento (glissando). In fact, the use of airshifts for shifts after the harmonic is only really obligatory when our shift is either long or fast. In the above examples, the shifts are all “fast” because we have two consecutive shifts: firstly up to the harmonic and then immediately down again. This type of fingering, with two consecutive shifts, can only be used (certainly in faster music) if one of the shifts is to a harmonic, otherwise, our intonation security would be dangerously unstable. To verify this, try transposing the above examples into keys in which we no longer have the possibility of using the harmonic: we will see that these fingerings are not at all transposable and therefore, in other keys we would need to completely refinger the passages.

In situations in which we don’t have two consecutive shifts up to and down from the harmonic we might – for both technical and musical reasons – want to keep our finger contact with the string during the shift down from the midstring harmonic rather than doing an airshift. Maintaining finger contact allows us to keep a real legato in the lefthand but also gives us greater positional security. This positional security advantage is especially important when our hand is coming down from the thumbposition because the release of both the thumb and the fingers that is required for an airshift of this type puts us in the situation of maximum positional insecurity (intonation danger). In these cases, the use of the harmonic before the shift is not to give us more time to do the shift but rather simply to give us intonation security on that note as well as allowing the hand to be totally relaxed before the shift:

Coming down from the higher intermediate region can also require a replacement of the thumb, if we have had our thumb up on the cello rib (see Intermediate Region). So, with an airshift down, we can once again find ourselves in the dangerous situation of zero lefthand contact with the fingerboard. Here also, in exactly the same way as for coming down out of thumb position via the harmonic, the maintaining of finger contact during the shift after the harmonic can be very advantageous:

Another way in which shifting during the harmonic is not quite the same as shifting during the open string is that, while we can play the open string with our left hand being absolutely anywhere on the fingerboard, in order to play the harmonic we have to start with our lefthand in the position of the harmonic. This means that our shifts “during” a harmonic are actually made after the harmonic, whereas our shifts “during” an open string really are made during it, rather than after it. Also, we may (as in the above examples) have to shift to the harmonic before our post-harmonic shift whereas we never have to “shift” to an open string (we just release our finger). For both of these reasons, we will normally have more time for the shifts when they are during an open string, compared to shifts after a harmonic.

To illustrate these differences, we can play the Schubert example with open strings instead of harmonics. The difference in the amount of time we have to do the shifts in the first two bars is quite extraordinary, the open strings giving us much more time than the harmonics:

The following links open up study material for working on this particular skill of shifting up to and down after a midstring harmonic. The exercises presented here are in a very long (7 pages), complete version, elaborated in the spirit of pure scientific enquiry, in which we will shift up to and down from the midstring harmonic on every finger, to and from every finger in the lower position. This may seem intimidating but is actually both a rich laboratory for experimentation and a good workout for this technique.

Shifts Up To And Down From Midstring Harmonic: EXCS Shifts After A Midstring Harmonic: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS