Cello Fingerings: Contractions and Snake-Crawls

When we bunch up our fingers, bringing them closer together than their normal semitone separations, we call this a “contraction”. A contraction is thus the opposite of an extension. The uses of these two words to describe our left-hand movements on the cello are unfortunately quite misleading in the sense that the ways in which they affect our hand at the cello are the exact opposite of the effects that we associate with them in ordinary life. Let me explain.

The word “extension” usually has positive connotations: of freedom, looseness, success, expansion, improvement, extending frontiers etc. When we extend something, we usually think that we are “opening it up”. When we extend a muscle, we stretch it, and we normally think of this stretching as having a loosening, relaxing, invigorating action. Extensions on the cello are however everything but that! (see Extensions/Hand Size).

In contrast to this, when something (anything) contracts – economies, building materials, fabrics, tolerance – it is usually considered as a negative, undesirable phenomenon. A muscular contraction, for example, is a tight, painful thing, associated with ideas of discomfort, excessive effort and tension. But once again (just like for the word “extension”), the situation for our left hand at the cello is in fact the complete opposite. Having our hand “contracted”, with the fingers bunched up together, each one touching its neighbours, is actually not only our most relaxed, comfortable, effortless, tension-free posture but is also our strongest and most stable! For these reasons, the contracted hand posture is not only our ultimate, ideal, resting posture but also our ultimate ideal playing posture!!! The contracted and extended hand postures could perhaps be more appropriately renamed as the “power posture” (contracted) and the “danger posture” (extended).

CONTRACTION SIZE

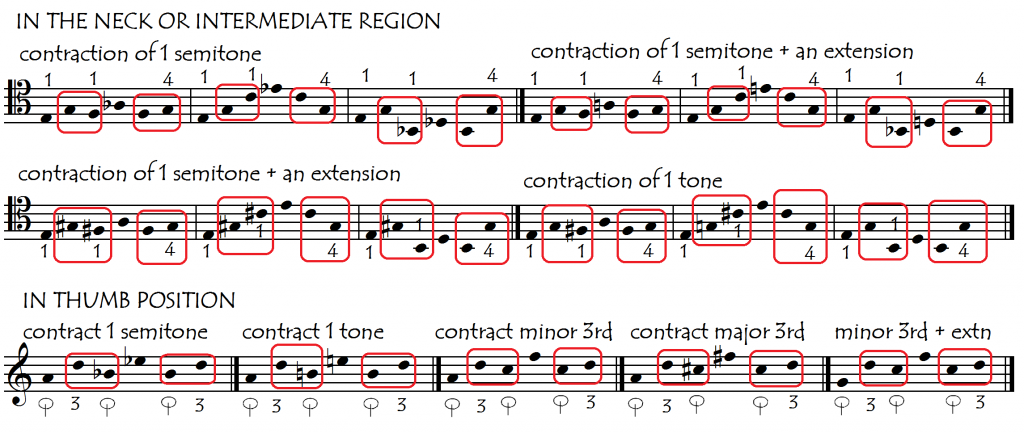

The size of any contraction can be measured in semitones. In the Neck and Intermediate regions, the biggest contraction we can do is of one tone, after which our contraction becomes a finger substitution (and after that, it converts into a scale/arpeggio-type shift [see below]). In thumbposition however, our contractions can be much greater because of the much greater distance range between the thumb and the higher fingers. The greater their size, the more potentially difficult and destabilising the contractions become, and the more time we need to be able to do them securely.

RELAXING FROM EXTD TO NON-EXTD POSITION: “CONTRACTION”, “RELAXACTION” OR “CONTRELAXACTION” ?

The relaxation of our hand from extended to non-extended position is also a “contraction” in the sense that the fingers come closer together. Even though the fingers do not come closer together than their normal semitone separation (hand range = minor third), the direction of the movement is exactly the same as for a contraction. But the fact that we don’t bunch up the fingers closer together than their normal semitone separation means that, rather than an active contraction, this movement is a simple release: a relaxation from the strain of the preceding extension which allows the fingers back into their comfortable “home position”. This is why we don’t consider this movement as a “contraction” but could invent a new, more descriptive name for it such as “relaxaction” or “contrelaxaction” which incorporates both the relaxation and contraction elements.

THE USES OF CONTRACTIONS

We use contractions a lot, probably even much more often than we realise, because in several of their most common uses we don’t actually sound the notes of the contracted fingers. So let’s start by first looking at these “secret” inaudible contractions:

1: VIBRATO

While we often need to maintain our hand posture in the “extended position” for long periods of time, we might think that we basically never play for more than an occasional moment in our “contracted position” (with a hand range of less than a minor third). Closer study reveals however that this is not true in the sense that, whenever we have a “long note” – and this happens an awful lot – we will tend to relax the hand into its compact, contracted position with all the other fingers bunched up around the playing finger. We do this because the extreme comfort, strength and stability of this posture greatly favour a beautiful, warm, healthy, stable vibrato (see the Vibrato page). This is, surprisingly, probably the most frequent, common use of contractions.

Apart from that, contractions are most frequently used as a component of (or as an alternative to) shifting, and for playing “squeezed” fifths. Let’s look now at these situations in detail:

2: CONTRACTIONS AS A COMPONENT (FACILITATOR) OF SCALE/ARPEGGIO-TYPE SHIFTS

Almost all Scale/Arpeggio-Type Shifts begin with a preliminary contraction movement. This contraction movement is useful (necessary even) for three reasons:

- it is one of the two essential preparatory movements that we need for our shift to be smooth and fluid (the other one is the elbow anticipation)

- it makes the shift distance shorter

- it means that we are shifting with the hand in its most stable, compact and powerful posture.

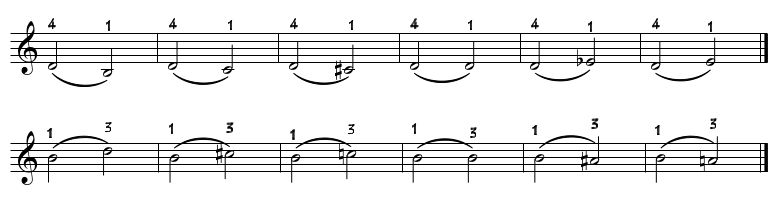

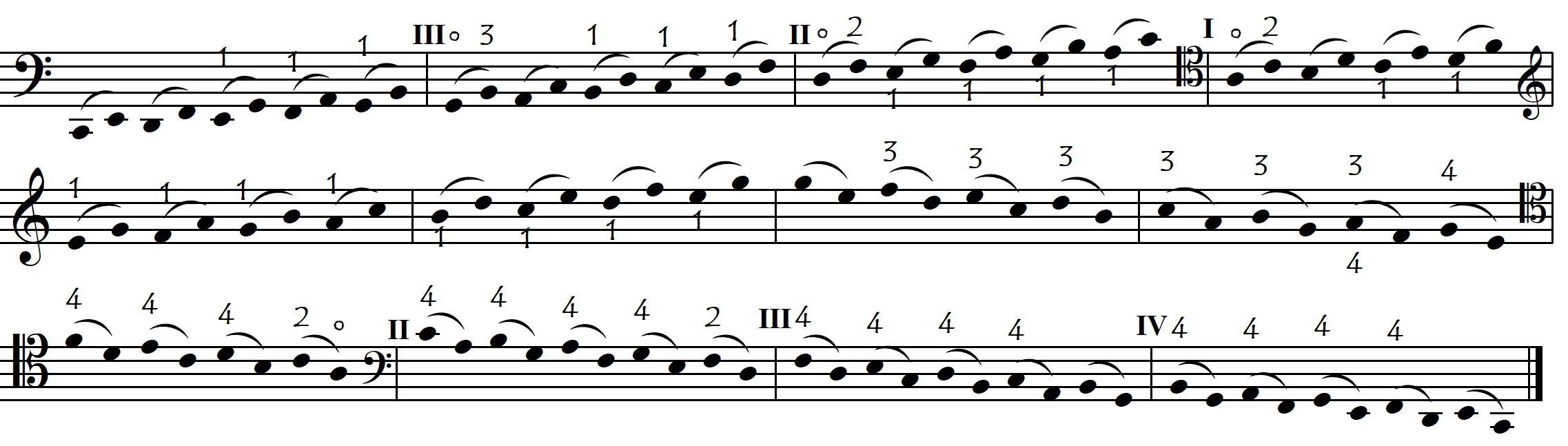

The scale/arpeggio-type shift is basically just a contraction movement that is continued further and further in the same direction as illustrated in the following sequence.

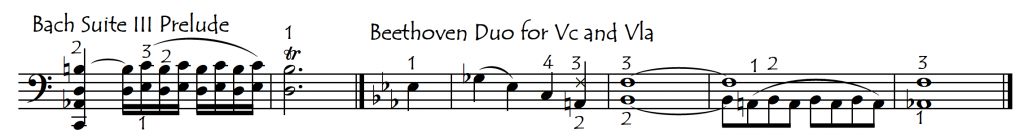

In the above examples, we can see that as the simple contraction movements of bars 3-5 amplify, they become Finger Substitutions. And when we amplify (continue) this movement even further in the same direction, it becomes a scale/arpeggio-type shift. This applies equally in all of the fingerboard regions:

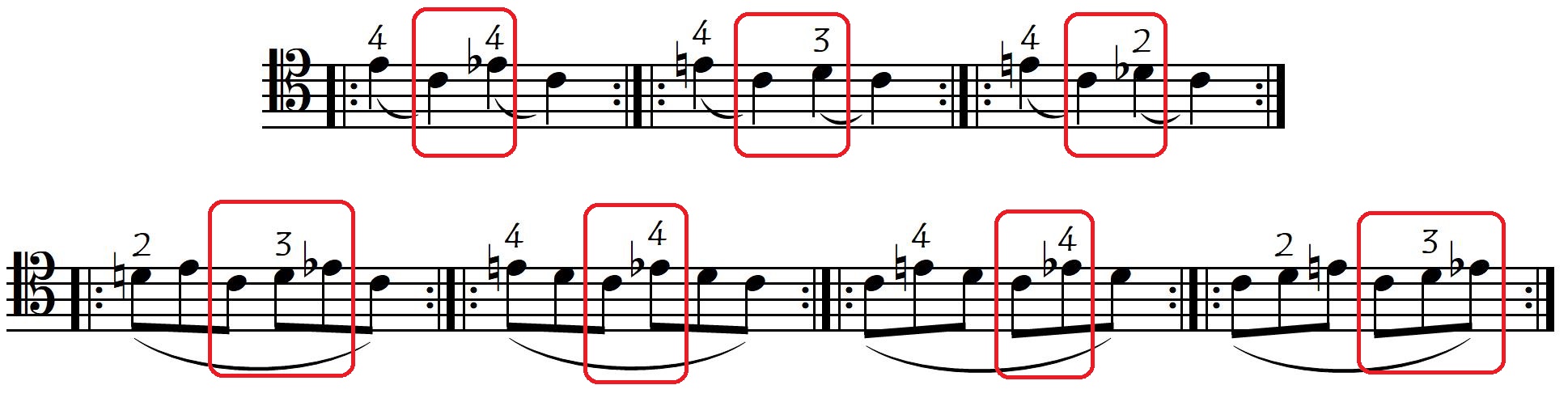

3: CONTRACTIONS AS A COMPONENT OF SAME-FINGER AND ASSISTED SHIFTS

The great strength and stability of the compacted hand posture greatly favour secure comfortable shifting for all shift types. No matter what the finger choreography, bunching the other fingers around the shifting finger always gives us a nice feeling. In same-finger shifts we probably do this without noticing, but in assisted shifts we may need to be more consciously aware of the possibility (and possible utility) of placing the “new” (target/destination) finger on its “intermediate note” in a contracted position. This means that we will place it on a note which doesn’t actually correspond to the one we would theoretically expect according to our normal uncontracted playing position. This is best illustrated with an example:

This use of contractions will be interesting mainly to very-small-handed cellists.

Now, having looked at our silent contractions, let’s look at the audible contractions, in which we actually play (sound) the contracted fingers.

4: SQUEEZED FIFTHS

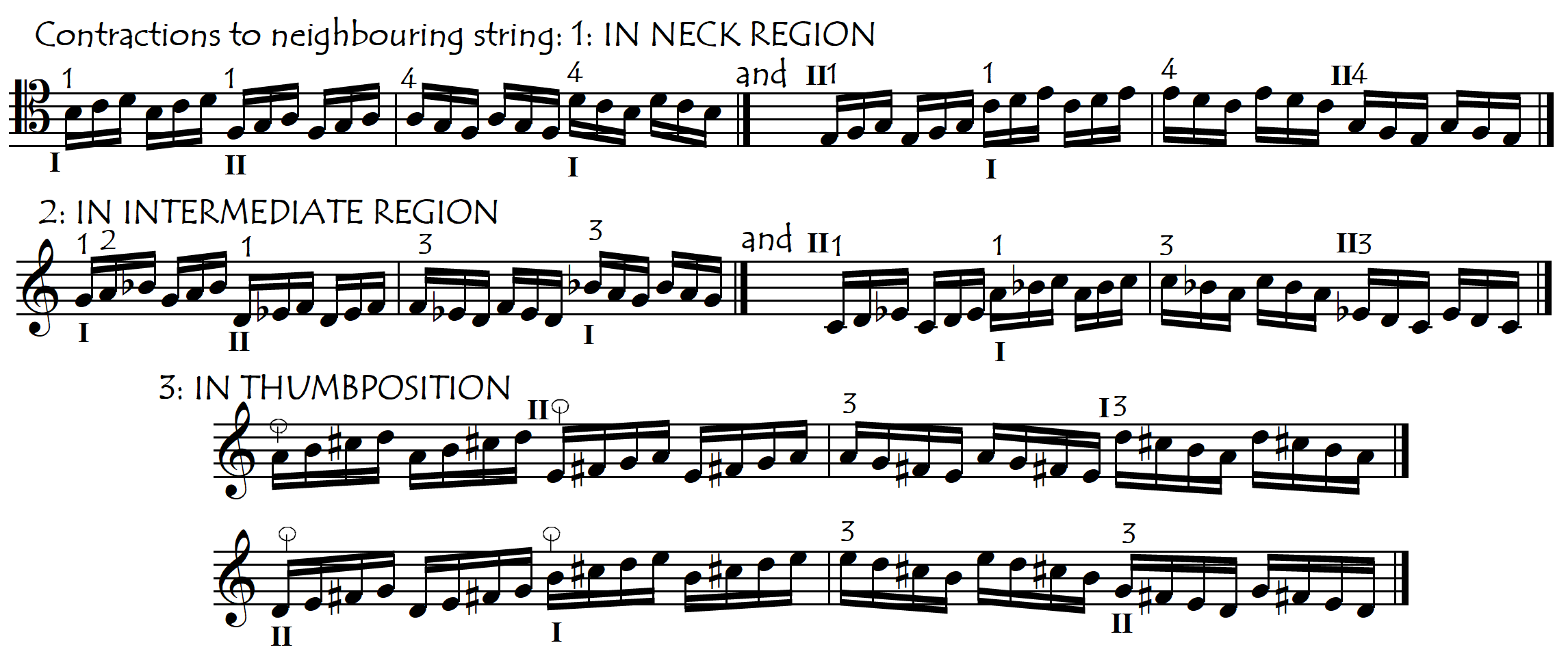

The “squeezed fifth” is actually a “contraction to the neighbouring string”. Here, we twist the left hand, turning it so the fingertips are now pointing towards the bridge (see photo). This allows us to play fifths with two different adjacent fingers. It also allows us to do a real vibrato on the fifth, which is especially important in slow double stops and chords. Because of the form (anatomy) of the hand and arm, this twisted posture is only practical when we place the higher finger on the higher string and the lower finger on the lower string (and not vice versa). Sometimes this contraction is followed immediately by the relaxation of the hand into the new position (one semitone away from the old position). At other times the “old” finger is maintained stopped and the hand remains in the same “position” (there is no shift).

The “squeezed fifth” is actually a “contraction to the neighbouring string”. Here, we twist the left hand, turning it so the fingertips are now pointing towards the bridge (see photo). This allows us to play fifths with two different adjacent fingers. It also allows us to do a real vibrato on the fifth, which is especially important in slow double stops and chords. Because of the form (anatomy) of the hand and arm, this twisted posture is only practical when we place the higher finger on the higher string and the lower finger on the lower string (and not vice versa). Sometimes this contraction is followed immediately by the relaxation of the hand into the new position (one semitone away from the old position). At other times the “old” finger is maintained stopped and the hand remains in the same “position” (there is no shift).

The smaller the hand and fingers, the more we will tend to use this technique. This is not only because it requires less brute force but also because small fingers actually fit “across” the fingerboard whereas big wide “sausage” fingers don’t. Therefore, cellists with small fingers may find it easier to use the “two-finger-squeeze” for fifths in situations for which cellists with large fingers may be quite happy to use just the one finger, squashed flat across the two strings.

In some passages in double-stops however, even the biggest, strongest hands are no solution and the “fifths-squeeze-contortion” is perhaps the best solution for all hands:

If we take these same passages and transpose them up into the Intermediate or Thumb Regions, we can see that we will use exactly the same “squeezed fifth” technique.

In fact, once we get above the neck region, the hand angle is such that it becomes increasingly difficult to use the flattened finger position but increasingly easy to use the “two-finger-squeeze” position (and, of course, the thumb). This is why the fingering for the following example from the Saint Saens Concerto would be so completely different it it was transposed down into the Neck Region.

5: THE SNAKECRAWL: CONTRACTIONS AS A FINGERING TECHNIQUE TO AVOID SLIDING SHIFTS

If, after doing a contraction, we then bring the rest of the hand and fingers into the new position, then we call this “snakecrawl”. In this way, instead of shifting the hand as a unit, we use a contraction to change our hand position. We will often use this technique to avoid audible, sliding or uncomfortable shifts, as shown in the following examples:

In the above examples, we stayed always on the same string, but we can also contract to another position on another string:

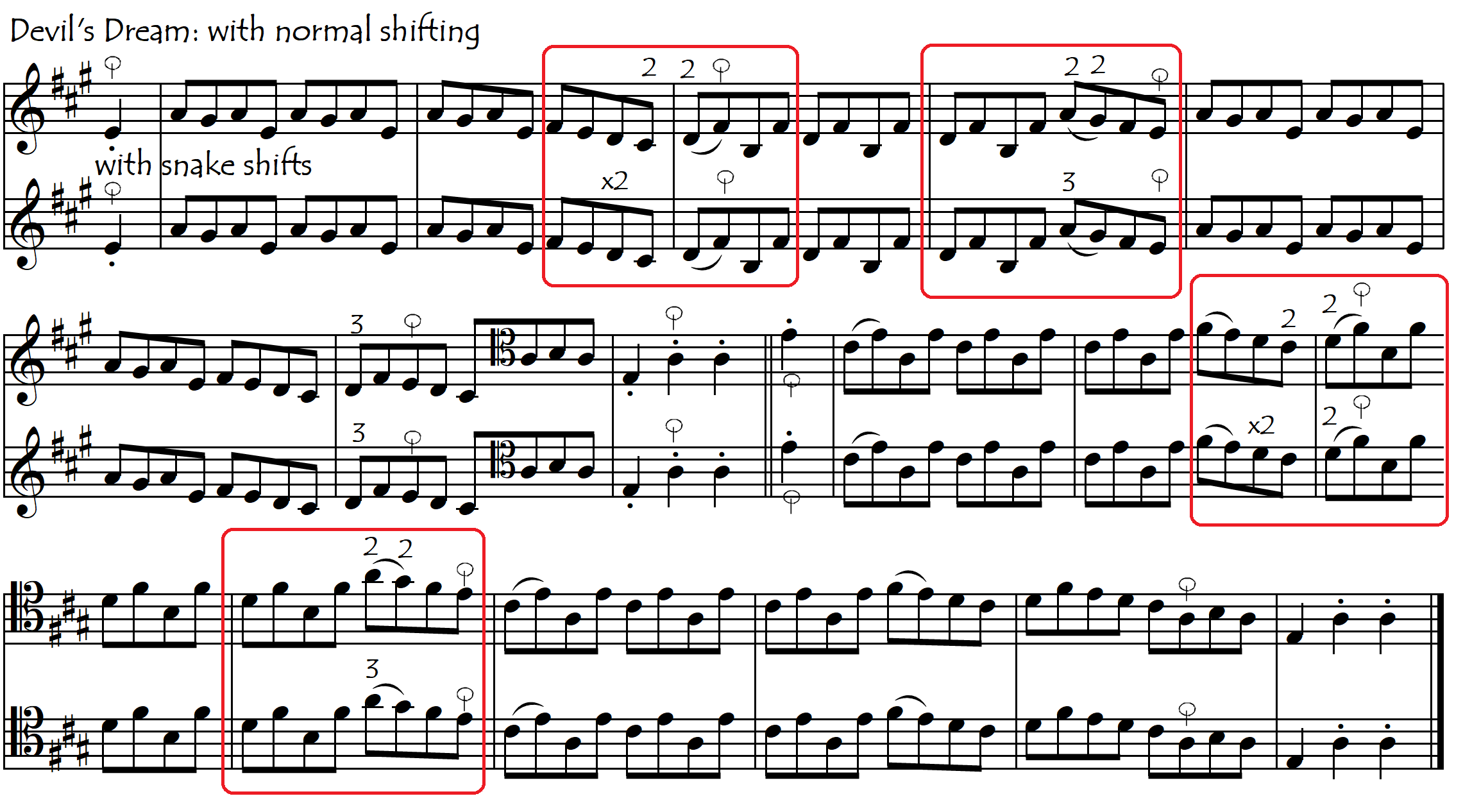

In snakecrawl passages, the way we move our hand to its new position is quite different from normal shifting. In a “normal” shift, the hand and arm move together as a single stable unit, but when crawling, one finger is always “still”, as if it were an “anchor”, giving our hand both physical stability and a stable positional reference from which to stretch or contract to the next position. When we use a series of contractions all in the same direction, we are thus moving in a similar way to snakes or worms, which is why we can call contractions also “snake-crawls”. Animals that have legs can move by taking steps, but snakes and worms cannot and are therefore obliged to move along by a series of contractions followed by extensions. We cellists can do both. The following examples illustrate the choice between “shifting” or “slithering”:

ARE SNAKECRAWLS REALLY NOT “SHIFTS” ??

We used the headings “no shifts” and “obligatory shifts” in the above examples to make very clear the difference between them. This is not however strictly accurate because this “alternative method” of moving the hand around the fingerboard via contractions and extensions is, in fact, a type of shift, but it is a very bizarre type. These snake-crawls can be considered as “Non-Whole-Hand Shifts”. They are called thus because, while the hand does ultimately change position (therefore it is a “shift”), it doesn’t change position as a unit but rather in the same way as a snake slithers along the ground: without taking any steps. Click on the highlighted link for more explanation of the concept of “Whole-Hand” and “Non-Whole-Hand” shifts.

SNAKES AND LADDERS: THE SNAKE-RACE

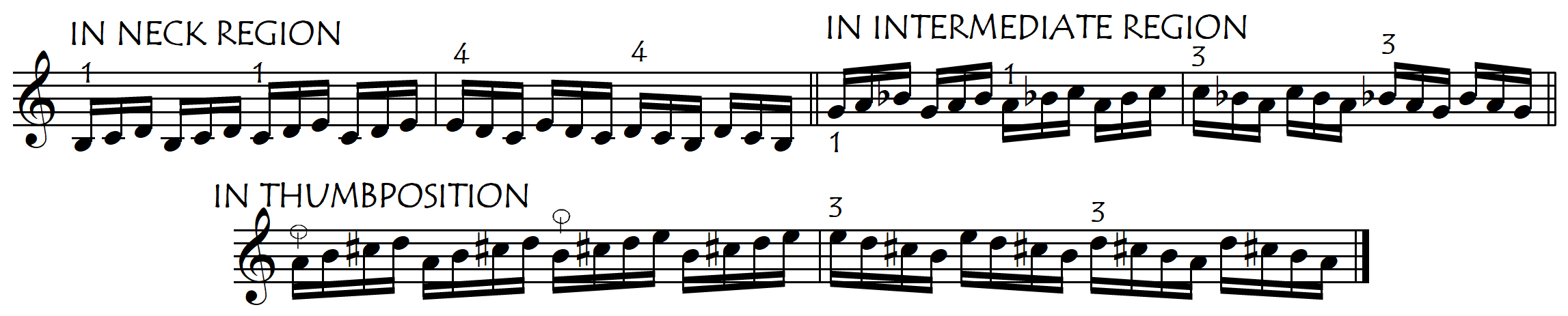

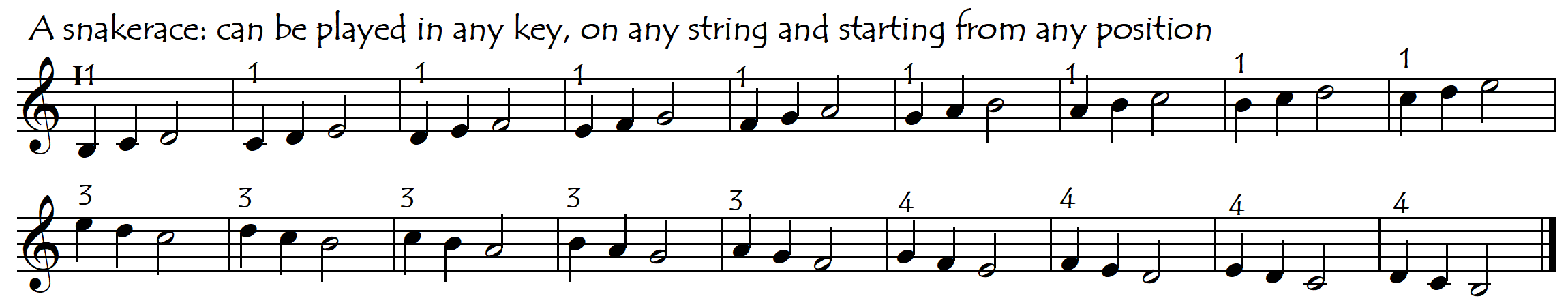

All of the above examples show single, isolated contractions in which our hand contracts up to a new position and then either stays in that new position or contracts back down to its original position. But what if we do a series of contractions all in the same direction, one after the other?

A “snake-race” occurs when we combine a series of contractions all in the same direction, one directly following after the other. This sequence of contractions followed by their relaxation into the new position (or sometimes even an extension) produces a movement that displaces the hand up or down the fingerboard by small increments (usually a semitone or a tone), but without requiring what we would normally consider “a shift”. Our snake-crawls are possibly superior to those of a real snake in the sense that, whereas snakes don’t normally crawl backwards, our crawls are equally useful for going forwards (up the fingerboard) as well as backwards (down). In either direction, a snakecrawl can start with either an extension or a contraction.

Here is another basic snakerace, this one goes a little faster and crosses all the strings:

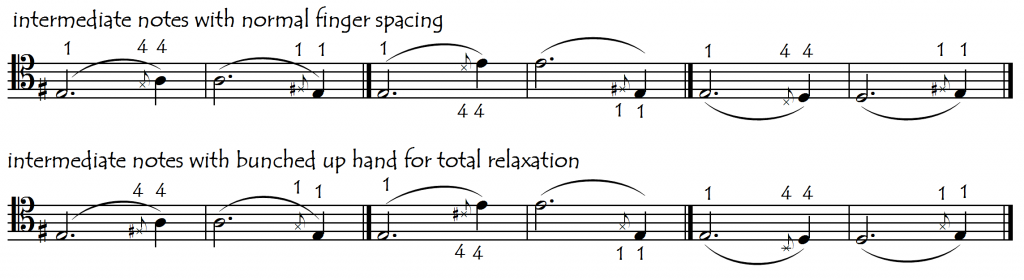

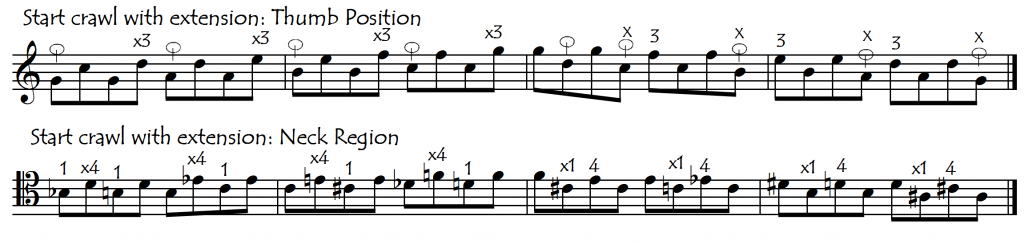

STARTING A CRAWL SERIES (SNAKERACE) WITH AN EXTENSION RATHER THAN A CONTRACTION

Snake crawls are simply an alternation of contractions and extensions. They don’t have to start exclusively with a contraction (as in most of the above examples): they can also start with an extension. This occurs very frequently in crawl movements involving the thumb, because of the enormous ease in making extensions between it and the fingers. And in fact, when we are using extensions in our crawls, we can slither along simply by “contracting” to a normal, unextended hand position after the extension as in the following two examples:

SNAKE PARADISE: THUMB POSITION AND THE HIGHER REGIONS

Snakes abound in hotter climates. On the cello fingerboard their favourite habitat is in the higher fingerboard regions where their size, diversity and frequency are favoured by two factors:

- the enormous freedom (and range) of movement of the thumb with respect to the other fingers, and

- the smaller distances between the notes up there

The increased possibilities for the use of contractions and extensions in thumbposition and in the higher regions in general is due to the fact that our hand range is greater in these two situations (i.e we have more possible notes “under the hand”).

WHY BE A SNAKE?

These “snake fingerings” can constitute a very valuable “trick”, especially useful for avoiding unwanted glissandi in small slurred shifts.

The need (or not) for these “snake-crawl” fingerings is very much influenced by bowing and articulation factors because we use these fingerings mainly to avoid shifting on slurs. For example, if we take the exact same note sequences as in the above examples but change the slurs and/or the rhythm as follows, we would no longer need to use contractions because we can now shift between the bow strokes:

TO SNAKE OR TO SHIFT?

Sometimes it is not clear which is better: to snake or to shift. Snaking avoids unwanted glissandi, but is often less secure for the intonation because there is no shift for us to hear (and thus control). When we shift, it is easier to measure the shift distance not only because we can hear the shift but also because we move that distance (interval) with the whole arm and hand. Snake movements are much less defined, which is no doubt why we use the term “snaky to describe someone whose intentions are not very clear.

Hand size is also a factor in our choice between shifting or snaking. A contraction relaxes the hand whereas an extension strains it. For a small hand, the use of contractions and snakes can be a way to reduce the time that our hand must spend in extension, most notably by avoiding the tension of shifts to/in extended position. For this reason, small-handed cellists may be tempted to use more contractions and snakecrawls in their fingerings than large-handed cellists.

Conversely, for large-handed cellists, contractions might well be more uncomfortable than the extensions that their use is designed to avoid, in which case those lucky cellists will have little need for contractions and will probably prefer to keep their use to an absolute minimum.

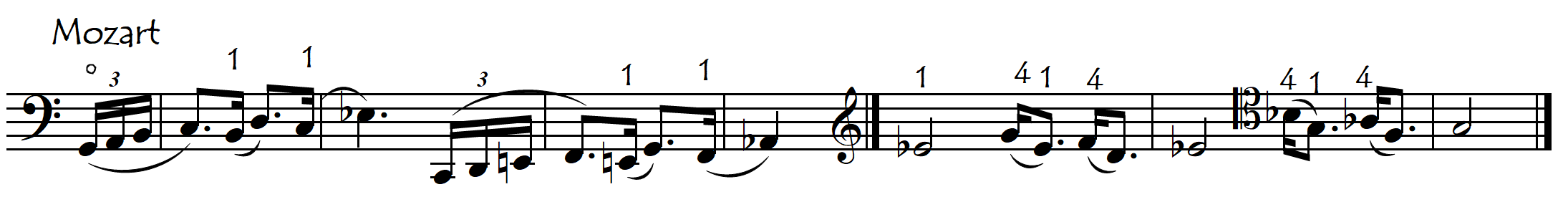

At other times, our choice is not influenced by hand size but simply by our subjective preference:

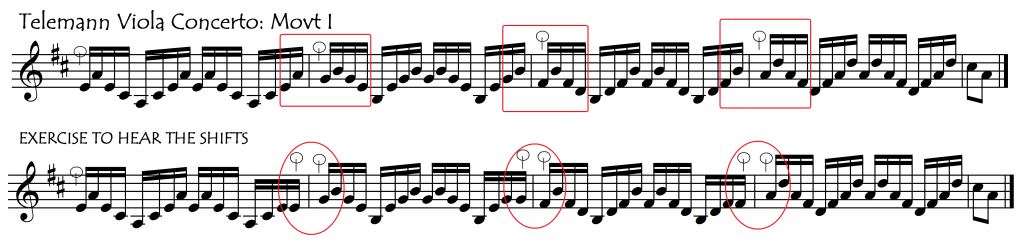

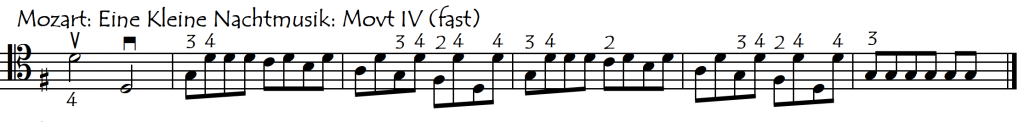

WHEN DEFINITELY NOT TO SNAKE: HIGH-DENSITY AND TURBO SNAKES

When we have too many snakecrawls one after the other in quick succession, we can lose our positional security. In other words, when the population density (or the size of the individual snakes) gets too large, snakes can become dangerous. Because snakes are Non-Whole-Hand movements, they can destabilise both our hand posture and our positional sense. At slower speeds, a single snake movement is not usually particularly problematic, but a longer chain of several of these movements following on from each other in quick succession can easily cause us to lose our intonation security, especially if they are big snakes. Doing snakecrawls is like using a ladder: going fast, and/or taking very large steps can be risky.

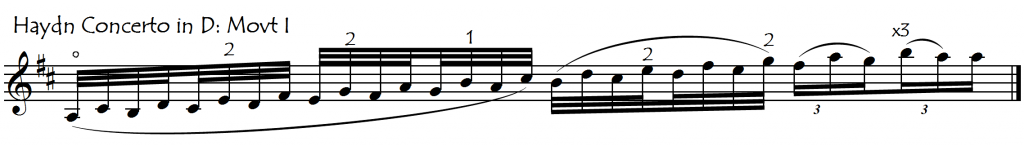

We could call these high-snake-intensity situations “turbo snakes”. This name reflects both their great displacement power and the potential risk of us not being able to control them. In these “turbo” situations we may therefore prefer to use “standard” fingerings with Whole-Hand-As-A-Unit shifts, because moving the hand around in “blocks” (stable, undeformable units) using audible and easily measured shifts, has a lot of advantages for our intonation security, especially in faster passages.

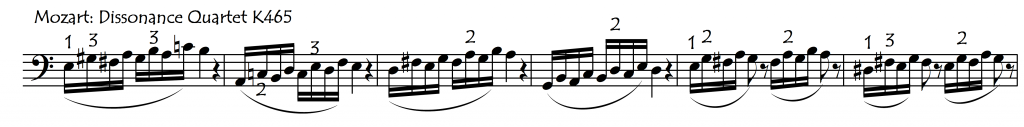

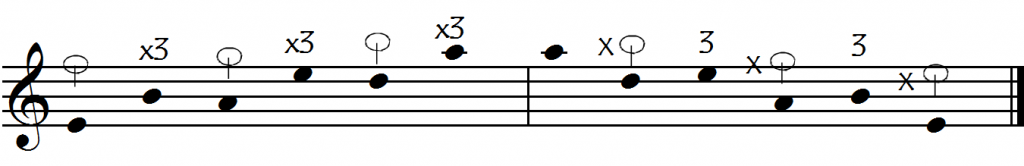

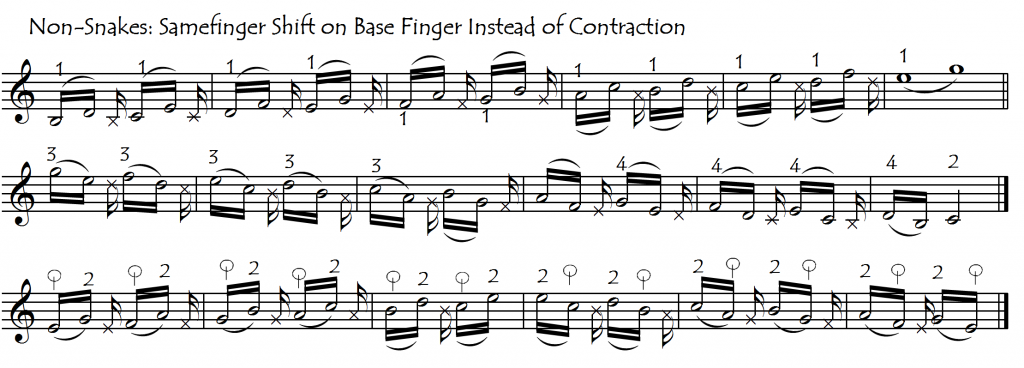

Large snakes are more dangerous than small ones. Sometimes the instability provoked even by a single (usually large or very fast) snake movement is such that we may also prefer to shift the hand in a block (without any contractions or extensions), even if we are unable to use our glissando to hear the shift. In these cases, we have to simply imagine the sound of the destination finger shifting. This can be made easier if we invent exercises to make the shift audible for practice purposes:

In these situations, rather than contractions, we are actually doing “same-finger-shifts” on the base (lowest) finger – either the thumb or the first finger. Here are some more examples of this:

Once again we need to find a way to practice these hand displacements in such a way that we can hear the shifts:

This type of alternative to snake crawls is easiest to see and understand in examples in which the top and bottom fingers are on two different strings which means they can both be left down on their respective strings during the shift (or snake) as in the following example. Here we shift on the first finger rather than contract.

This musical example can be used as the basis for a practical exercise to illustrate and work on this type of shift:

Snakecrawls and snakeraces constitute one of the most obvious uses of our contractions because here – unlike for the use of contractions in vibrato and shifting as explained at the beginning of this article – we do actually sound the notes that are played by the contracted finger(s).

PRACTICE MATERIAL FOR CONTRACTIONS, SNAKECRAWLS AND SNAKERACES:

Snakecrawls In The Bach Cello Suites: REPERTOIRE COMPILATION

Chromatic Semitone Contractions On One String: All Fingerboard Regions: No Extensions: EXERCISES

Isolated Pairs Of Contractions To Alternate Between Neighbouring Positions: EXERCISES

Tonal Snakeraces: All Strings: All Fingerboard Regions: EXERCISES