Cello Spiccato: Practice Material for the Bounce

The bouncing bow is not used much in great singing Romantic melodies. In fact it is not used much in melodies at all and, apart from some virtuoso spiccato showpieces (and the second movement of Elgar’s Cello Concerto), most “solo repertoire” doesn’t normally give us enough material to really dominate this technique, especially at faster bouncing speeds. In this sense, spiccato for the bow is like thumbposition for the lefthand: a very specialised, absolutely essential technique, which will probably need to be worked on in a dedicated and specific way with its own specialised practice material.

Ricochet and sautillé are more sophisticated techniques, but because they are just specialised variations of the bouncing bow, basically all of the following discussion about spiccato can be considered as preparation for both of these two techniques. Specific practice material for ricochet can be found by clicking on its highlighted link.

WHAT PRACTICE MATERIAL SHALL WE USE?

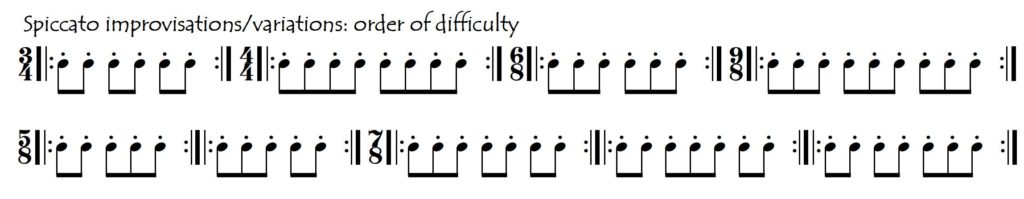

We don’t actually need much formal “material” on our music stand to be able to work on our spiccato. All we really need is a little imagination ……. and a metronome. A good starting point is simply to put on the metronome (at any speed) and start improvising. We can find any appropriate bounce speed by simply subdividing the metronome beat into three, four, five, six, eight etc. We can also convert basically any music (exercises, scales, arpeggios, studies, pieces) into spiccato study material, once again by simply subdividing every beat into smaller units.

When composing the second movement of his Cello Concerto, Elgar seems to have done this process in reverse: perhaps he didn’t realise that not only was it great music, but also that it was probably the best (certainly the most virtuosic and musically inspired) spiccato study that exists!

All of the above examples use binary (duplet and quadruplet) rhythms. We can however also do our spiccato improvisations and variations in ternary (triplet) groups. These are slightly more complicated for the bow because of the alternation between up and down bows at the beginning of each successive triplet group. Triplets that are grouped in pairs (as in 6/8) are a little easier for the brain than triplets are grouped in “threes” (as in 9/8). This is because each group of six notes always starts with the same bow direction (usually a downbow), whereas with groups of nine notes, every second group of 9 starts with the opposite bow direction. This means that the logical progression of increasing difficulty (practice order) would be from binary groups (of two and four) to ternary (compound) groups of six followed by groups of 9. Then we could add the strange, highly asymmetrical groupings of fives and sevens as the ultimate bounce-coordination challenge …….

REPERTOIRE COMPILATIONS

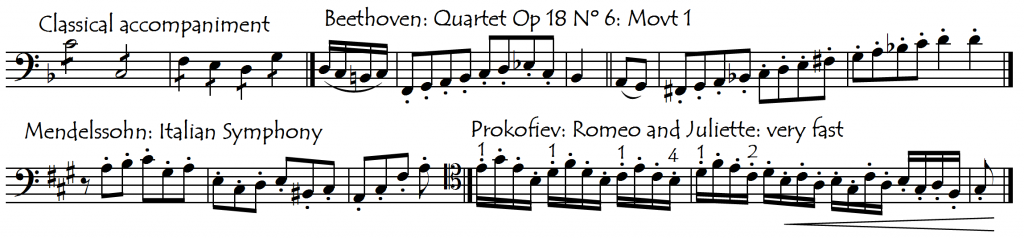

Just like for thumbposition, we can make repertoire compilations of spiccato passages. These have the added benefit, with respect to studies, that we are actually learning/practicing repertoire at the same time as working on our spiccato. And this will not only be “solo” repertoire because it is actually in the accompaniment passages of chamber and orchestral music where extended (lengthy) spiccato passages really abound (excuse the pun!!!). One advantage of accompaniment passages over “solo repertoire” passages is that many of these accompaniment passages are more harmonic/rhythmic than melodic and therefore do not involve great lefthand complications, which makes them especially useful for learning this bow technique. String chambermusic cello parts are usually especially full of these rhythmic harmonic spiccato passages because this accompanying function is very often the principal role of the cello in string chamber music. In chambermusic with piano however the cello is usually treated as a more melodic instrument.

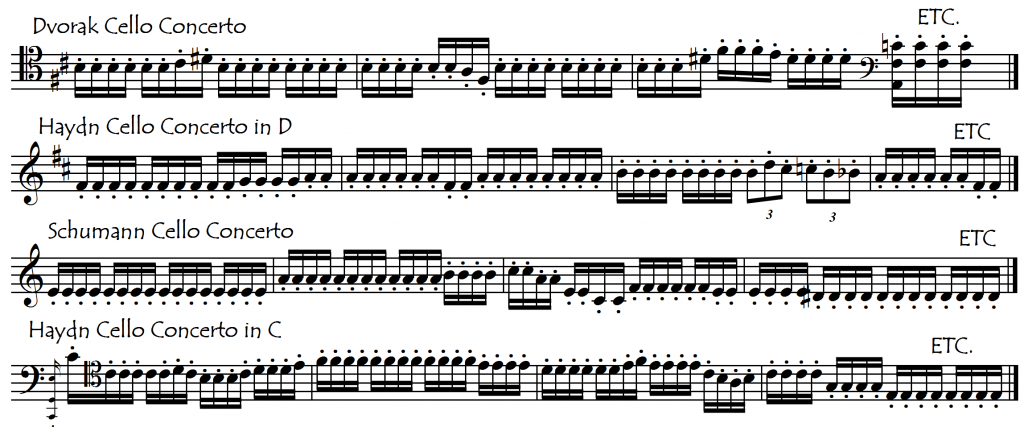

Here below we have made a short list of some of the movements of cello repertoire which contain a lot of spiccato passages. We can use this material like (or instead of) studies:

Brahms Sonata Nº 2: Movement III. This movement has a “Scherzo and Trio” form and whereas the Scherzo (the first part) uses almost entirely spiccato bowings, the contrasting Trio is just one long legato melodic line. Brahms’s spiccato is quite different (typically much heavier) than many other composers and here we don’t want our spiccato to be too short.

Mendelssohn’s spiccato, even though he was also a germanic composer and a contemporary of Brahms, is very different to that of Brahms, and the fast movements of his (Mendelssohn’s) symphonies and chamber music are just full of long and interesting spiccato passages in which absolute lightness is often the priority.

SPICCATO THROUGH THE MUSICAL EPOCHS: A NATURAL PEDAGOGIC ORDER

Fortunately for cellists, playing spiccato on the same note repeatedly – as occurs in so many of the accompaniment figures and harmonies of chamber and symphonic music of the Baroque and Classical Periods – is not only the easiest way to learn spiccato, but also is the most common form of spiccato that we will encounter. However, as the cello became more and more used as a melodic instrument in the Romantic period, the use of spiccato in melodic figures (rather than in harmonies and bass lines) became more common. Spiccato “melodies” are usually more difficult than spiccato harmonies because as a general rule the notes change faster in the melodies than in the harmonies. Thus there is a definite progression towards greater left-hand virtuosity in spiccato passages as musical style evolved through the centuries, as the following examples illustrate:

This is why, in our repertoire compilations, we would do well to start with music from the Classical Period and work upwards through the stylistic periods. While 20th century music uses spiccato in the most extreme ways, Mendelssohn is perhaps the king of “classical spiccato”. His music is often so light and so fast that it demands the highest level of spiccato virtuosity. For this reason, Mendelssohn provides some of our best repertoire study material. Tchaikovsky also gives us a lot of fast, virtuosic material. Stravinsky’s spiccato is very often of the driest, spikiest (shortest, most vertical) kind: with him we have reached about as far from Brahms’s spiccato as it is possible to go.

LEARNING SPICCATO PROGRESSIVELY

Apart from the fact that the chronological order coincides roughly with increasing technical complexity, our repertoire compilations do not have a carefully structured pedagogical order. To build up our spiccato (or any skill) progressively, it is useful to work through material of gradually increasing complexity. This complexity, for spiccato, comes from the addition of note changes, shifts and string crossings. To be able to concentrate on the bounce, it will help to reduce both the left-hand difficulties and the string crossing complications, so initially, the less note changes the better. Playing all the different rhythms and speeds on one note is deadly boring so a good compromise is perhaps four bowstrokes per note, which gives us plenty of time to prepare for each note change so that the bow’s bounce is not disturbed.

Because shifting and articulating new fingers are lefthand actions, not surprisingly, they disturb the bow’s bounce much less than string crossings, so we will really need to work especially hard at our spiccato string crossings. Surprisingly, speed is not always a factor of difficulty for spiccato. It can be harder to control a medium-speed spiccato than it is to control a very fast spiccato.

But independently of the speed, the fact that spiccato is so rhythmically regular means that it benefits very much from being practiced not just “with a metronome”, but with the metronome at the highest possible click-rate. This doesn’t mean “at the fastest possible tempo” but rather that, for any particular tempo, the metronome should be set to the smallest possible note values (for example, at the speed of eighth or sixteenth notes rather than quarter notes). In this way, a maximum number of its beats coincides with our notes, which makes it easier for us to really control well the regularity of our bow bounce.

The chronological order of our repertoire spiccato compilations creates an approximate pedagogical order of increasing difficulty/complexity but we can do better than that. Any spiccato passage can be simplified and we can reduce even the most complex passage to an exercise on one string and in one position, only then gradually adding the string crossings and shifts. The easiest simplification for working on difficult spiccato passages is to play them without the left hand (on open strings). To work on fast spiccato passages we can play two bows on each note to reduce (halve) the frequency of both the lefthand changes and the string crossings. Playing with three bows to each note is even more interesting as this triplet rhythm means that the beats – and the string crossings – come alternately on down and up bows. This is good practice for coordination and for “reverse” bowings.

On One String: Few Shifts

On Two Strings: Few Shifts And Crossings

On Two Strings: Many Shifts And Crossings

On Three Strings: Few Shifts And Crossings

On Three Strings: Many Shifts And Crossings

On Four Strings