Cello Technique: Bow Trajectory On The String

There are several main concepts that we can look at in a discussion of the cello bow’s trajectory on the string. Please note that bow changes and bow trajectory in the air are not discussed here: they have their own specific pages (click on the highlighted links).

“UP” AND “DOWN” BOWS: THE CONFUSIONS OF LANGUAGE

The terms “up bow” and “down bow” represent quite a strange use of language as the directions in which the bow actually travels have very little to do with the traditional concepts of “up” and “down”. Had Isaac Newton played the cello he might have been quite confused about the meaning of these words and might never have discovered gravity! Only if we play the cello while lying down, on our right side and on the edge of a bed or sofa, will the terms “upbow” and “downbow” accurately reflect the bow stroke directions!

These terms, of course, come directly from violin playing, and would indicate in fact that the violin used to be held in a position more rotated clockwise than nowadays (in the gipsy/country-fiddler posture). In this position, the violinist’s arm really does “push up” for the up-bow and “pull down” (or fall down) for the down-bow. Certainly for the cello, the words “to-the-left” and “to-the-right” would be more appropriate descriptions of the bow directions than “up” and “down”, but, just like for our inappropriate tuning in fifths, the cello is part of the violin/viola family and we have adopted their customs and language even when not appropriate, rather like a younger brother who has to wear his sister’s pass-me-down clothes!

The french have a different way of describing the two bow directions: they use the terminology of “push-pull” rather than “upbow-downbow”: the upbow is called “pushed” (poussé) while the downbow is called “pulled” (tiré). This also is a somewhat strange use of language because a push-pull movement usually refers to a movement that is made in an axis towards and away from the body, as if the bow were a saw (or a sword!) pointing straight out in front of us. In spite of this directional confusion, “push” and “pull” are still a more helpful way of describing the bow-stroke directions than our english “up” and “down”, because “push” and “pull” both imply that we are working against a certain resistance in each direction rather than just going with gravity (down) or against gravity (up) which, as we have seen, is misleading. The terms “push” and “pull” are also better than “up” and “down” because they imply (correctly) that we are using different muscles in each direction, rather like a tennis player’s “forehand” and “backhand” strokes. And what’s more, these terms (push and pull) are as valid for violin and viola as they are for cello and bass.

The origin of the bowing symbols is both curious and revealing. The downbow sign evolved from the letter “n” while the upbow sign evolved from the letter “v”. These letters were the abbreviated forms of the latin words “nobilis” (meaning strong, noble) and “vilis” (meaning exactly the contrary). See also the article “Choosing Bowings”

STRAIGHT BOW

Nature is just not made of (or for) straight lines. This is unfortunate for string playing because the most basic objective of our bow trajectory is that the bow must travel more or less in a straight line, perpendicular (at 90º) to the string axis. If it doesn’t, the string cannot vibrate freely, the sound will be bad and the bow changes can sound scratchy.

Using the bow is like driving a car: we have to direct the bow along the path that we want it to go along. Unfortunately, there is one very important difference that makes steering a bow more difficult than steering a car. To drive a car in a straight line, you don’t need to “do” much because a straight line is the easiest, most natural trajectory for a car. But for a hand holding a bow, a straight line is the most difficult and unnatural trajectory. It requires us to “do” a lot with our right arm in order to avoid the bow trajectory being a natural wide arc around the axis of the body (as all beginners will discover).

So, how do we achieve this “straight” bowstroke ? We do this through a combination of finger, wrist and elbow compensations that could be likened to “folding” the right arm on the upbow, and “unfolding” it during the downbow. To complicate matters, we humans come in an enormous variety of body shapes and sizes, whereas cellos have much less variation in dimensions. Some of us have long arms, others have short arms. The longer our arms are, the more we will need to use this folding and unfolding of the right arm in order to keep the bow’s trajectory at 90º to the string. Let’s look in more detail at the different movements that we can use in our basic bowstroke (bow trajectory):

CURVED, FLOWING, ARM MOVEMENTS: THE “THERAPEUTIC ARC” AND THE HORIZONTAL “8”

Apart from achieving a “straight” bow, our other main objective for the bow trajectory is to incorporate into it a maximum of circular, flowing, flexible “cushioning” movements. As a general rule, we want to avoid:

- straight mechanical lines (in everything but the bow’s actual trajectory)

- stiff, abrupt changes of direction.

It is curious, fortunate, funny – almost miraculous even – that it is only through the exploitation of the extreme flexibility of the right elbow and wrist that we are able to pull a “straight” bow. With a rigid stiff arm and wrist, the bow automatically describes a perfect arc around our body. This movement is great for some athletics events (throwing the discus) but is totally disastrous for cello bowing because the bow would only be parallel to the string for a short time in its middle section. In other words, a rigid, straight arm gives an unwanted semicircular bow trajectory that we could call the “stiff-arm-beginners-arc”, while mobile wrist and elbow joints give us a nice straight bow trajectory.

A very healthy bow exercise – and in fact quite a useful bow technique – is to deliberately make the opposite movement to the unwanted “beginners” arc described above. To do this we need to push our bowhand further away from the body as we bring our bow out towards the tip, rather than letting it follow its natural trajectory around the body. And likewise, as we come in towards the frog, we will need to bring the elbow in closer to the body and angle the hand so that the bow tip is pointing further away from our body rather than pointing around it. If the “beginners-bow-arc” is convex (with our body at the centre), then our therapeutic “artists-arc” is concave, as though the centre of our bow arc is a point about 1m in front of our body. In the diagrams below we are looking at the cellist from directly above. The cellist is the rectangle, and the arc that the bow describes is the curved line. The first diagram shows the “beginners” (convex) arc, and the second shows its contrary: the “therapeutic” (concave) arc.

We don’t need to make this arc very pronounced in order for it to be therapeutic. As with all new movements, it helps to exaggerate it at first in order to encourage the learning process, but if we permanently adopt the extreme version then the therapy could become a new problem in itself ! One of the dangers of the “therapeutic arc” is that it can encourage the point of contact at the tip of the bow to systematically move away from the bridge. This is absolutely the opposite of what we want to do ! We need the tip of the bow to stay near the bridge, even nearer than we were at the frog and in the middle of the bow, in order to compensate for the lack of natural bow (and hand) weight out there at the point.

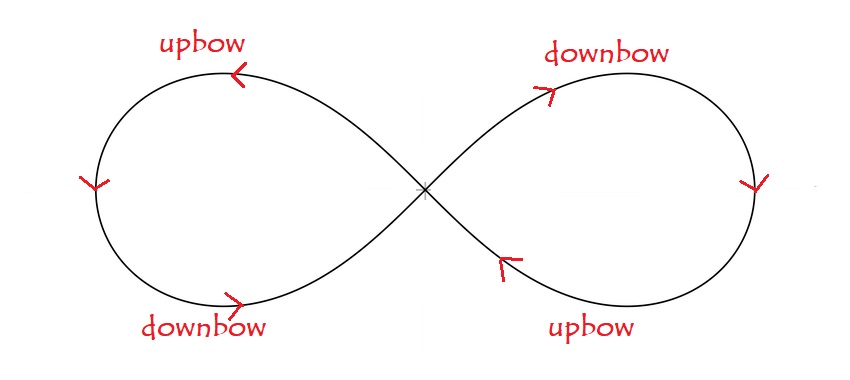

THE HORIZONTAL FIGURE 8 LOOP

We can incorporate this therapeutic arc into our bow changes, making a small, discreet figure-eight movement at each bow-change. The following diagram exaggerates enormously the amplitude of this movement in order to make the concept clear.

Flexibility and mobilisation of the right wrist and elbow joints are like magic keys that unlock the doors to an artistic world of expressivity, flow and bowing freedom. With a flexible elbow and wrist, we will not only sound better but will also look better and even feel better: music and musicality are, after all, more about dancing than about machine robotics! And not only will we enjoy ourselves more (dancing is more fun than being a sewing machine), we will also avoid repetitive strain injuries. Let’s look now in more detail at the different components of these wrist and elbow movements in the bow trajectory.

THE WRIST

The wrist joint is very complicated, as anyone who has ever broken their wrist will know (there are 8 bones in there). It is the most complicated joint in the human body. So why does it have so many bones? Why is it so complicated ? ……………. In order to allow the enormous flexibility that the human hand needs in order to operate our sophisticated tools (of which the bow is perhaps one of the most ultra-sophisticated).

The wrist is such a hugely important topic that it has its own dedicated page here:

THE ELBOW: THE HINGE, THE LEVER, THE WING AND THE SLOW-MOTION FLAP

In order to keep the bow at 90º to the string (to avoid it making a wide arc around our body), we need to open out the elbow joint as we go out to the tip of the bow, and close it as we come back in towards the frog. This, we learn from the very beginning because it is absolutely essential.

There is however another elbow movement which, although not as obviously essential, can be very helpful, adding considerable flow and smoothness to our bow strokes. We are talking here about a vertical movement of the elbow in which the upper arm (from shoulder to elbow) comes (falls back) closer to the body on the upbow, and lifts up and away from the body on the downbow. These rises and falls of the elbow are a little like the flapping of a bird’s wing (in slow motion). It’s funny how the names “downbow” and “upbow” are once again misleading because the elbow moves in fact in exactly the opposite direction: on the downbow the elbow moves up, and on an upbow the elbow moves down. To verify this idea, try doing the contrary elbow motion and see how it feels: quite probably it doesn’t feel good at all!

There is however great variability between different cellists in the use of our right “wing” (elbow) and how much we “flap” it. We might be tempted to think that the degree of elbow vertical mobility is a reflection of the cellist’s temperament. For example, part of Lluis Claret’s elegance, refinement, poise and Buddhist calm at the cello comes from his very sober use of the right elbow: he likes to keep the raising of the elbow on the downbow to a minimum, preferring instead to apply the extra weight (that we need as we move out towards the tip) from the shoulder, which is also kept low. Following this “temperament” hypothesis, we could expect that a very exuberant cellist like Jaqueline du Pre might have a more active “wing” but, surprisingly, this is not the case. Further study of videos of the greatest cellists leads us to conclude that raising the elbow as we go out from the middle of the bow to the tip is not a great idea and that the greatest benefit of the elbow’s vertical wingflap is principally in the lower half of the bow.

This vertical elbow movement, used with great moderation and in the lower half of the bow, makes a perfect dance partner for the wrist which, in a movement described in more detail on the Wrist page, arches higher on the upbow as we come in towards the frog. Lowering the elbow on the upbow encourages (or even obliges) the hand to hang lower from the wrist as otherwise the bow would be lifted off the string (by the lever movement).

RAISED ELBOW FOR PLAYING LOUDLY? …….. OR HAND PRONATION ?

One way of applying extra weight to the bow for loud playing is by raising the elbow, as though it were a lever which, by being raised higher, facilitates the application of pressure to the bow/string. But there is another, alternative way to apply more weight to the bow which doesn’t require the raising of the elbow: the pronation of the bow-hand. Lluis Claret, a master of the elegant, ergonomic, unflappable bowstroke, recommends the wrist pronation alternative, not only for louder playing but also for playing chords.

THE ELBOW ON AN UPBOW DIMINUENDO

It is, in fact, this combination of the wrist and elbow movements that makes the lowering of the elbow on the upbow such an important component of those particularly difficult diminuendos-a niente (diminuendos to nothing) upbow strokes that end with the ever-so-gentle, imperceptible removal of the bow from the string. Lowering the elbow gently pushes the wrist higher, and ultimately “sweeps” the bow off the string in a beautiful smooth flowing movement, almost as if we were pushing the bow out of the water from underneath. This lowering of the elbow on the upbow diminuendo is quite counterintuitive because when we think “lift the bow gently off the string” we intuitively want to lift the whole arm from the shoulder. But no! Whole-arm-lifting is what we do on a downbow diminuendo, whereas on an upbow diminuendo we use this totally different technique that we could perhaps call the “Mermaid Push” because the gentleness and grace with which the bow parts company with the string is similar to how we might imagine a mermaid emerging from beneath the surface of the water.

CONCLUSION TO WRIST-ELBOW FLOW

These vertical movements of the wrist and elbow are classic examples (illustrations) of the curved, open-ended, smooth, flowing, expansive, dancing movements that we are looking for in all areas of our playing – in contrast to mechanical, rectilinear, sewing machine movements. We can play a perfectly straight bow stroke without these vertical components ….. but encouraging these movements gives us so much more lightness, flow, control, grace and beauty. I am convinced that these two movements are good repetitive injury prevention aids for the right arm.

LOOPS AND SWIRLS: PARASITES OR PEARLS?

Some conductors have such flowing movements that their body language becomes so unclear as to be almost unintelligible: we no longer have any idea where the beat is. The same can happen to the right arms of string players in the sense that if we allow our circular, flowing movements of the hand, wrist and elbow to become too large then our bow stroke can become grotesque, comical and impossibly complex. Probably the golden rule with respect to these movements is “smaller is better”. Some very fine cellists maintain that, rather than filling our bow trajectory with cushions, springs, and figure-eights, we just need to have supremely careful control at our bow changes, especially at the frog.

CONTROL OF POINT OF CONTACT

The place where the bow hair touches the string is called the Point of Contact. We need to control this point well because if we don’t, then the bow’s uncontrolled movements, towards and away from the bridge, will not correspond to the musical necessities and will cause problems of bad sound etc. One common problem of bow trajectory occurs when we let the point of contact inadvertently stray further away from the bridge during our downbows. In the case of long downbows, this means that the tip of the bow might have drifted up over the fingerboard by the time we get out to the point. This is exactly what we do not want to be doing because it is precisely at the tip of the bow that we have much less natural weight, and therefore it is there that we need the bow to be nearer the bridge rather than further away. Lluis Claret makes two recommendations with regard to avoiding this problem:

- that we make a conscious effort to bring the tip of the bow closer to the bridge as we move out towards the point on our downbows

- that when we start a long upbow at the tip, we should consciously start with the tip near the bridge.

THE UPBOW

Can you imagine being scared of upbows for 35 years? I was! To avoid slow upbows, especially those with diminuendos, I would spend enormous amounts of time changing and rechanging my bowings. Orchestral playing was often very uncomfortable because I couldn’t change the bowings for the whole orchestra. Sometimes I would beg the group leader to change a bowing – just for me and my problematic upbow. How embarrassing! That was until a cellist friend told me “raise your wrist on the upbow”. Never have 6 words made such a difference ………

It can be a very useful idea in fact to think of the upbow as being led by the wrist. This means that the wrist joint not only raises up a little during the upbow stroke, but is also increasingly inclined to the left (in advance of the fingers). It is as if the wrist was being pushed along by the elbow against a certain resistance, rather like the front of a boat pushing through the water, with the driving force coming from the propellers (elbow) at the back of the boat. See the page dedicated to The Wrist.

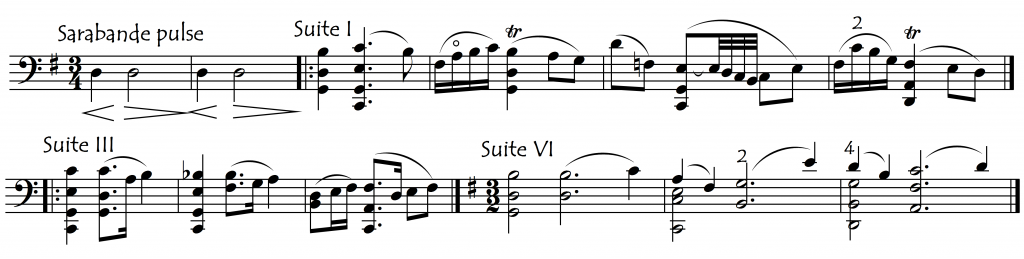

Allowing the elbow and upper arm to come lower and closer to the body (as discussed above) also helps with the upbow, especially on an upbow diminuendo to nothing. Here, if we think of this elbow/arm movement as following through with a slight rising up at the end of the falling arc, this gives us the gentle lift that we need to take the bow off the string with the greatest delicacy (see “Bow Trajectory in the Air”). In fact, the long slow upbow diminuendo is one of the most delicate and difficult bowing manoeuvres. Slowing the bow down and simultaneously relaxing the pressure is so much easier and more natural to do on a downbow than on an upbow. Experiment, for example, with the Sarabandes from the Bach Cello Suites, playing their characteristic “short-long” pulses starting both on up and downbows to see the difference in bowing comfort.:

It is so much more comfortable to play the shorter faster-bow-speed crescendo stroke of the first beat on an upbow, with the longer slower diminuendo stroke on the down-bow. In fact the terms “upbeat” and “upbow” are very similar ……. they would seem to be made for each other! In the Sarabande, the “upbeat” is simply displaced to the first beat of the bar.

Think how common it is for pieces of music to finish on a long, gentle fade-out, and yet how rare it is for string players to choose to do these endings on an upbow: in fact, we will usually go to great lengths to avoid this at all cost. However, as with extensions – and other unnatural but unavoidable components of cello technique – we need to be able to master this skill …….. therefore we will probably need to practice it! Our objective is not to finish every fade-out piece on an upbow, but rather to be able to feel comfortable with the unavoidable slow upbow diminuendos that will inevitably appear from time to time in the middle of our pieces. For practice and repertoire material for working on this skill (apart from the Bach Sarabandes with “reverse bowing”) click on the following link:

Slow Upbow Diminuendos: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

USING THE ENTIRE LENGTH OF THE BOW

It is very easy to get into the habit of not making use of the entire length of the bow. This is because we seldom “need” the bow’s two extremities (tip and frog): we can usually manage OK without those few centimetres of bow hair at either end. But this doesn’t mean that using these extremities is not very useful at times, and it is certainly a good habit to get into.

It is especially easy to get into the habit of avoiding using the frog of the bow, probably because this is the most uncomfortable part of the bow to use. Bow changes, string crossings and weight control are all more difficult at the frog than in the middle and for this reason, we will often instinctively avoid going all the way to the frog, on even the longest up-bows. Unfortunately, this natural avoidance of the frog has the effect of making us increasingly uncomfortable there. If, on the contrary, we deliberately fight against this natural tendency, and insist on bowing all the way to the frog whenever possible and appropriate, then we will find ourselves becoming more and more comfortable at the frog. If we can become comfortable at the frog with our bow changes, string crossings and arm weight control, then this will make playing in the middle of the bow seem even easier. Practising at the frog is like doing gymnastics with heavy boots on: a wonderful preparatory exercise that makes everything that comes afterwards seem easy.

It is also easy to forget that the tip of the bow exists. This is a shame because playing at the point of the bow gives such a beautiful gentle sound, with an easily-achieved imperceptible start and finish to the stroke, and an effortless seamless legato. Of course, it does require a certain effort on the part of the arm: we really do need to reach the arm out far (especially for the “A” string) and this can be tiring if we need to stay in this position for a long time.

CONCLUSION

It is surprising how many factors are actually involved in what seems like such a simple task – just pulling a bow across the string from one end to the other. We need to be able to observe all of these factors and one of the best ways to do this is by playing in front of a mirror. We tend to watch our left hand instinctively but now we must make the effort to watch our bow and right arm. To see the bow angle and point of contact, it may help to rotate our seat clockwise a little so that our left side is turned slightly towards the mirror. To watch our right arm, however, it is better to be directly facing the mirror, or turned a little to our left (anticlockwise), with our right side turned towards the mirror.

Sometimes while playing, we may find that our attention is taken away from the bow by technical difficulties with the notes we are playing. It is precisely at THESE moments when our bow might go crooked or our point of contact might go wandering. That’s why the best way to observe ourselves is actually by recording ourselves on video while in a performing situation. In these circumstances, we will not normally be thinking about anything but musical communication so we will see our bowing in its authentic, unconscious, automatised, natural state.