Bach: Cello Suite Nº 5 BWV 1011: Discussion

Click here for the downloadable sheet music.

DISCUSSION

Bach also arranged this suite for lute. The lute arrangement is – unlike the cello suites – in Bach’s own handwriting (manuscript) and this autograph manuscript is available on www.imslp.org. The lute arrangement is catalogued as BWV 995 and is in G minor (instead of our BWV 1011 in C minor). This manuscript is a great help in our elaboration of the various editions of this suite. It is especially useful as a guide for the second cello’s “walking bass” accompaniment in the duo-cello version, because Bach often adds this very same type of bass line to his lute version.

The Fifth Suite has two special characteristics that differentiate it from the other Suites: the scordatura tuning and the prevalence of dotted rhythms. Curiously, both of these characteristics are somewhat optional: we can decide whether to play scordatura or not, and we can decide also how much to dot the dotted rhythms (“double-dotted” or “as written”). Another peculiarity of this suite, shared also with the Sixth Suite, is the frequent use of chords and doublestops. Let’s look now in greater detail at these three characteristics.

1: THE SCORDATURA EFFECT

The scordatura tuning is a wonderful effect – the suite definitely sounds different (much better) when played with this tuning – but OMG it certainly complicates things for the player, especially if we want to play it from memory. At some stage we will probably need to decide one way or the other (with or without scordatura), because maintaining both versions securely in our memory would be a feat reserved only for geniuses and chess-masters. The best way to find out which way we would like to play it, is by actually trying it both ways – with the music of course.

Before we decide between playing this suite with or without the scordatura, let’s look at some of the main effects (positive, negative and neutral) of the scordatura tuning in this suite

1A: SCORDATURA FREES UP THE LEFT HAND:

The scordatura tuning allows our left hand to cross between the A and D strings much more fluidly and easily in this awkward key of C minor. Now we can use the open A-string to avoid entirely the need for the horribly awkward double extension between the first finger Bb on the A string and the 4th finger Ab on the D string that so complicates music in Eb major for cellists. What’s more, the scordatura tuning also allows us to use fingerings that remove other simple extensions (also uncomfortable) on the A string and between the A and D strings. We could even consider the idea that perhaps Bach decided on this tuning after hearing how bad his Fourth Suite (also with 3 flats) was sounding on normally tuned cellos! In terms of the use of extended positions on the two higher strings, tuning the A string down a tone makes playing in three flats the same as playing in C major with normal tuning. The scordatura makes this Suite MUCH easier technically for the left hand, especially for a small hand.

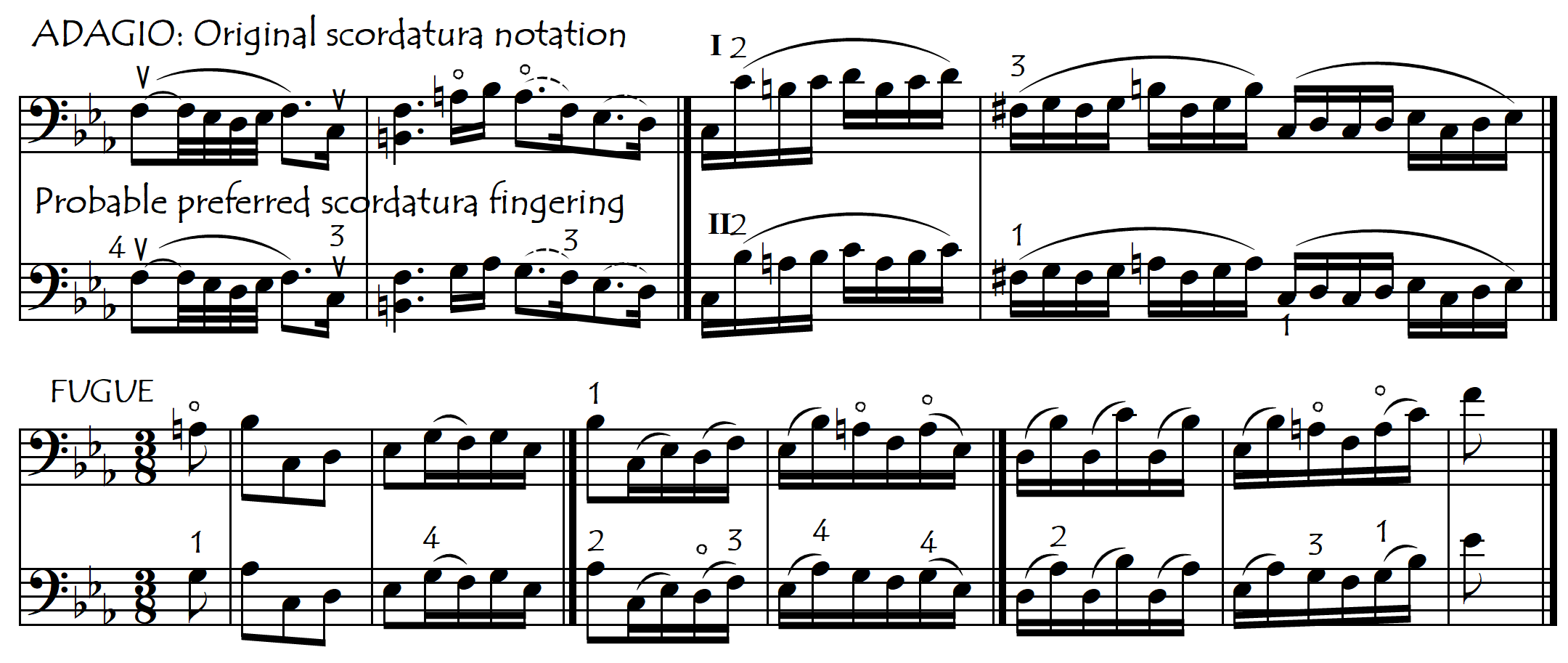

Let’s look at some examples, comparing the fingerings of certain passages played with and without scordatura, to show how Bach’s tuning frees up our left hand by removing extensions:

1B: SCORDATURA GIVES INCREASED RESONANCE AND INTONATION SECURITY

The use of the open A-string not only adds comfort for our left hand, it also adds both resonance and intonation security to our playing in this normally-awkward key of Eb major.

The following table shows how much more the top open string is used in this suite when playing with scordatura compared to when playing with normal tuning. Not surprisingly, in the key of C minor, the G is more commonly used than the A natural. This heightened use of the open string with the scordatura tuning not only frees up the left hand and permits more chordal writing, but also gives greater resonance to the suite in general.

|

USE OF THE TOP OPEN STRING IN BACH’S SUITE Nº 5 |

||

|

WITH SCORDATURA |

WITHOUT SCORDATURA |

|

|

Prelude |

13 |

9 |

|

Fugue |

44 |

22 |

|

Allemande |

19 |

10 |

|

Courante |

15 |

6 |

|

Sarabande |

0 |

0 |

|

Gavotte 1 |

24 |

8 |

|

Gavotte 2 |

7 |

0 |

|

Gigue |

7 |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

129 |

56 |

1C: SCORDATURA ALLOWS MORE CHORDS AND DOUBLE STOPS:

Because the open A string now sounds as a G, the possibilities for chords and double stops in the key of C minor (both with the open “A” string but also using it stopped) are now greatly enhanced. In fact, as shown in the table at the bottom of this page, the Fifth Suite has more chords and double stops than the First, Third and Fourth Suites combined (205 compared to 169) and has twice as many as the Second Suite (which was the previous “champion” for chords and doublestops). This gives the Fifth Suite an extraordinary resonance and harmonic (vertical) richness that sets it apart from the previous suites.

1D: SCORDATURA MAKES PLAYING FROM MEMORY MORE DIFFICULT:

While the scordatura makes the Fifth Suite sound much more resonant, and makes playing it much easier, it does however make memorising it much harder. Why is this ?

When playing without music (from memory), unless we have a photographic memory, we normally play more “by ear” than when we are reading a printed score. With no written score to tell us what notes and fingers to play, we have to imagine (sing) the piece in our heads just a tiny bit in advance of our fingers (see Anticipation). When playing from the written music, by contrast, we don’t need to imagine anything before we put the fingers down: we can just “play by numbers” as it were, reading (instead of singing) a little bit ahead of our fingers.

Unfortunately, with the scordatura tuning, the fingers on the A string no longer make the intervals with the fingers on the D string that we have been programmed to expect by our many years of playing the cello. Our ear will tell us to put down a finger that will now sound one tone too low. Suddenly, a written fourth sounds a third, a written fifth sounds a fourth etc. Those basic intervals that we have spent a lifetime playing with the same fingerings now require new, bizarre fingerings. This is confusing enough in “normal”, linear, monophonic writing such as in the Fugue of the Prelude, the Sarabande and the Gigue, but becomes much more problematic in the double stops and chords (broken and “real”) that are so frequent in the other movements of this suite (as we can see in the table above). The first Gavotte is particularly difficult to memorise in its scordatura version because of the density of this “harmonic”, vertical writing.

It is this need to override (ignore) – or temporarily retrain – our ear, that makes memorising the Fifth Suite (when played with scordatura) so difficult. There is a way out of this complication: instead of sacrificing the scordatura in order to make the memorising easier, we could choose to play it with both the scordatura and the written music. That way, we get the benefit of the authentic scordatura sound and chords, while at the same time eliminating the danger of memory lapses. After playing it enough times with the sheet music on the stand, we should ultimately be able to memorise it – it just needs more time than other pieces with normal tuning.

1E: SCORDATURA MAKES IT MORE CONFUSING TO READ

Because of the scordatura tuning, all of the notes higher than “G” on the D string can be written in two ways depending on which string they will be played on. If they are notated by Bach at the pitch at which they sound, this implies that they should be played on the D string, whereas if they are written one tone higher they are obviously intended to be played on the A string. This can make the reading very confusing because for any of these eight pitches (G, G#, A, Bb, B, C, C# and D), in order to know which note is really meant by Bach, we need to know previously on which string it will be played.

In three of the four existing historical manuscript copies of the Bach Suites, this Suite is notated with the scordatura tuning, and in all these manuscripts the “implied fingerings” are normally identical. Therefore we can safely assume that this was Bach’s original notation. We could be very “historically authentic” and decide to play Bach’s exact fingerings – who would dare to rewrite the bible ?! This certainly would take away all reading problems because our fingerings would coincide perfectly with Bach’s notation. But we may want to change his implied fingerings because, unfortunately, they are not always necessarily the best ones. This is because he – no doubt to avoid this confusion in the reading – only notated notes up the “D” string (higher than first position) when it was absolutely unavoidable (for obvious reasons of shifting, fingering, bowing, phrasing etc.). When in doubt, his “default option” was to notate on the A-string. This means that, for many passages, the fingerings implied by the notation are undoubtedly not the most appropriate either musically or technically, and we may therefore want to change them. The following examples are taken from the first few pages of the Prelude and Fugue but many many more follow:

Unfortunately, if we do want to change which string we play some of these notes on, then our fingering change requires a change in the written pitch of the note. So unless we make our own edition (and rewrite the notes every time we change our fingering) – or follow Bach’s original choices which respond more to rule than to musicality – there will probably be many passages in this Suite where we are not playing what we are reading, on both the D string as well as on the scordatura A string. This is why reading (and not only memorising) this Suite with scordatura notation is doubly difficult.

2: CONSEQUENCES OF PLAYING IT WITHOUT THE SCORDATURA?

Let’s look now at the principal effects (good and bad) of playing this suite without the scordatura tuning. We could simply read the above points (the effects of playing with scordatura) from the reverse point of view, but for absolute clarity we will specify some of the most significant consequences here below.

2.1: WITH NON-SCORDATURA WE NEED TO REWRITE THE IMPOSSIBLE NOTES

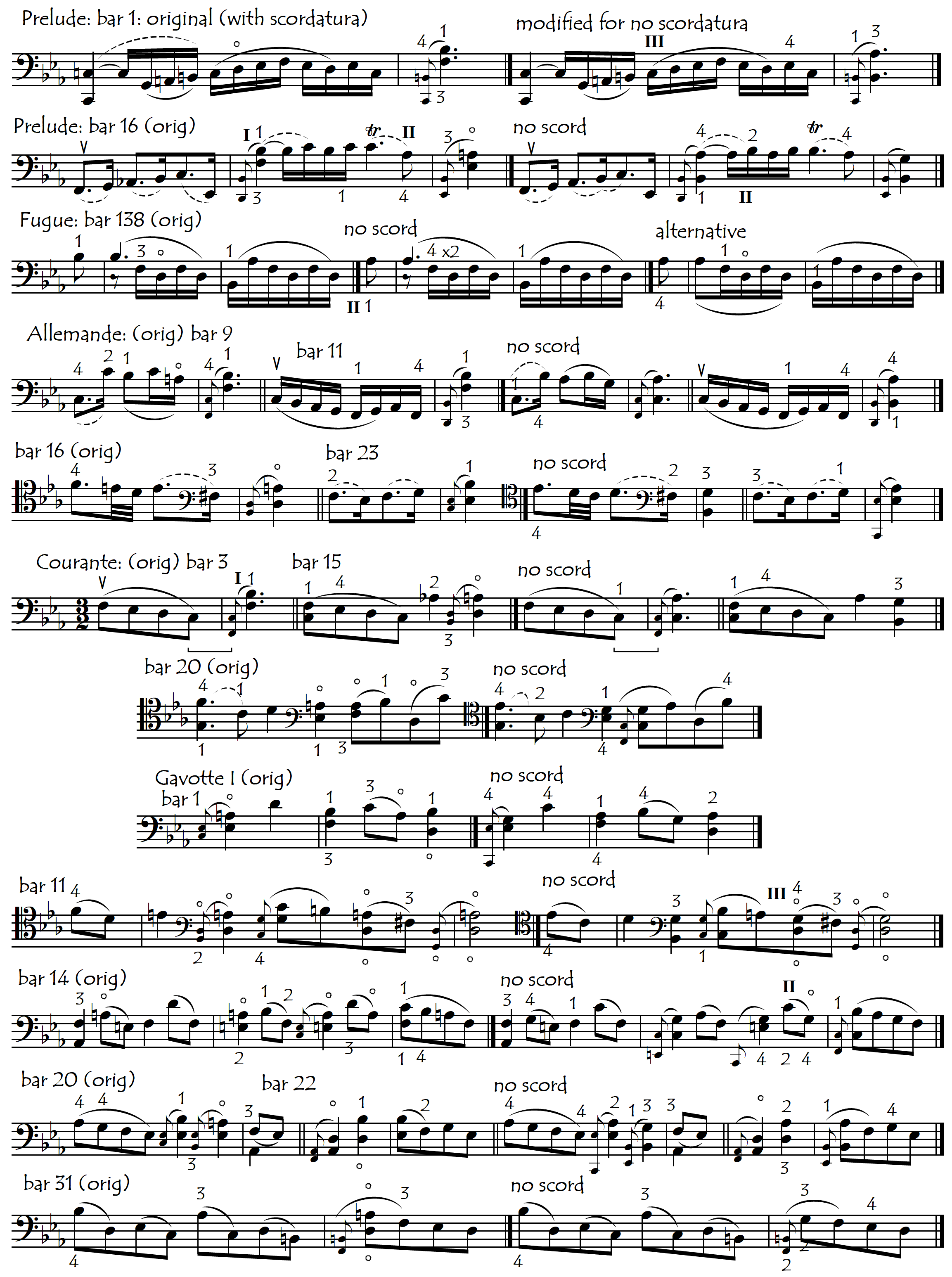

The version of this suite for non-scordatura cello is somewhat of an “arrangement” of the original, mainly in the sense that approximately 20 chords or doublestops (in the entire suite) need to be revoiced. This is because these chords can’t use the top string as intended by Bach, and are therefore either no longer possible, don’t resonate well, or are extremely awkward to play. These obligatory revoicings don’t however seem to negatively influence the musical line or the harmonic effect in any significant way. There are also two unisons which are not possible in the non-scordatura version. Here are the majority of these revoicings. On the left-hand side are the original scordatura chords while on the right side are the non-scordatura revoicings. In a few cases (for example in bar 11 of Gavotte I), we are able to substitute the top open string (G) with the octave harmonic on the G-string:

This compilation of the modifications necessary for non-scordatura playing can be downloaded or printed from the following link:

Obligatory Modifications for Non-Scordatura Playing Of Bach’s Fifth Suite

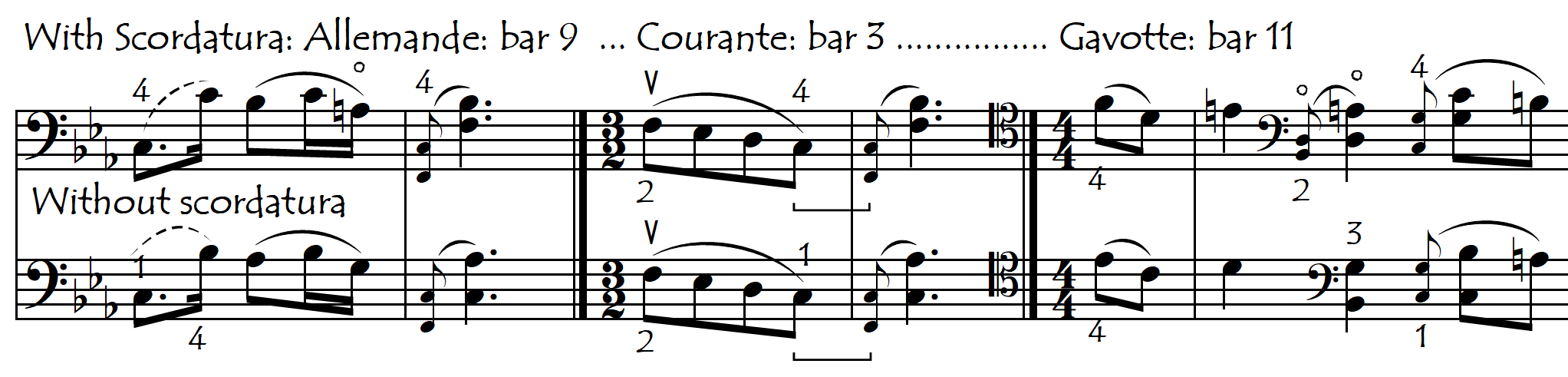

Surprisingly – and happily for non-scordatura players – some of Bach’s original scordatura chords are actually significantly more awkward than their non-scordatura versions:

In fact, in the cellofun scordatura versions, some of these most awkward chords have been substituted by their easier non-scordatura variant. Even if we decide to play these awkward chords as Bach voiced them, in general, the scordatura version is easier to play than the non-scordatura arrangement.

2.2: WITH NON-SCORDATURA WE CAN PLAY IT ANYWHERE AND ANYTIME

The scordatura tuning doesn’t just destabilise the A-string. It destabilises the other 3 strings also and both the instrument and the strings require time before they eventually stabilise with the new tuning. Playing without scordatura means we no longer need to retune the cello many times before, during and after our foray into the suite. With scordatura, it is as though we are going from a cosy room out into a freezing winter night: each time we pass through that door, we are obliged to do considerable redressing in order to adapt to the new conditions.

2.3: NON-SCORDATURA IS EASIER TO MEMORISE

Without scordatura, we no longer have to override our inner ear and the automatic fingering principles that we have spent so many thousands of hours reinforcing over our many years of cello playing. For the brain, we are speaking a familiar language and don’t need to do any reprogramming.

CONCLUSION: SCORDATURA OR NORMAL TUNING ?

The authentic version is definitely with scordatura, but if our priority is to play this suite without making our life any more difficult than necessary, then we may well prefer to play it with normal tuning. Possibly the least bad solution would be to play it scordatura but with the written music (not from memory). That way, we get the benefit of the authentic scordatura sound and chords and its greater ease of playing, while at the same time eliminating the danger of memory lapses. In any case, while the differences between the two versions are enormous for cellists and specialists, for the normal, unspecialised listener, the differences between the two versions are probably barely noticeable.

*********************************************************************************************

Let’s look now at some of the other main characteristics of this suite:

2: “FRENCH STYLE”: DOTTED RHYTHMS

If we look at the following table referring to the use of dotted rhythms in the Bach Cello Suites, we can see that this Suite not only has many more dotted rhythms than the others, it actually has more of them than all the other suites combined! The Gigue and the Allemande are especially densely dotted, the Courante and the introduction to the Prelude also. We can choose to “double-dot” these dotted rhythms, playing the short notes (the ones after the dot) both later and shorter than written. This accentuates the dotted effect, giving the unique (but optional) “French Style” which so characterises this suite and about which we have spoken on the page dedicated to “Dotted Rhythms“.

|

FREQUENCY OF DOTTED RHYTHMS IN THE BACH CELLO SUITES |

||||||

|

SUITE 1 |

SUITE 2 |

SUITE III |

SUITE IV |

SUITE V |

SUITE VI |

|

|

PRELUDE

|

0 |

10 (16) |

0 |

3 (6) |

Prelude 44 (52) Fugue 2 |

0 |

|

ALLEMANDE |

18 |

14 |

3 |

0 (1) |

78 (82) |

33 (45) |

|

COURANTE |

3 |

2 (6) |

0 (4) |

0 (2) |

34 |

0 |

|

SARABANDE |

7 (9) |

4 (19) |

10 |

43 (44) |

0 |

31 (43) |

|

GALANTERIE I |

0 (2) |

0 (1) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

GALANTERIE 2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

GIGUE |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

63 |

0 |

|

TOTAL |

28 |

30 |

13 |

46 |

221 |

64 |

In the above table the numbers in brackets include the “doubtful dots” – see the Dotted Rhythm page for a further discussion about this subject.

3: HIGH FREQUENCY OF CHORDS AND DOUBLE STOPS

The following table looks at the Suites from the point of view of their use of chords and double stops.

|

NUMBER OF CHORDS AND/OR DOUBLE STOPS IN THE DIFFERENT MOVEMENTS OF THE BACH SOLO SUITES (excluding drones and repeated double stops) |

|||||||||

|

Prelude |

Allemande |

Courante |

Sarabande |

Minuets |

Gigue |

TOTAL |

|||

|

Suite I |

1 |

7 |

2 |

11 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

24 |

|

|

Suite II |

6 |

16 |

5 |

26 |

34 |

0 |

20 |

107 |

|

|

Bourees |

|||||||||

|

Suite III |

11 |

11 |

1 |

25 |

4 |

1 |

7 |

60 |

|

|

Suite IV |

6 |

3 |

11 |

44 |

1 |

20 |

0 |

85 |

|

|

Gavottes |

|||||||||

|

Suite V |

26 |

31 |

35 |

65 |

0 |

48 |

0 |

0 |

205 |

|

Suite VI |

6 |

24 |

0 |

69 |

42 |

45 |

33 |

229 |

|

We can see from the above table that the Fifth Suite is much more chordal than any of the previous suites. In fact, it has more chords and double stops than suites 1, 3 and 4 combined and has almost double the chords as the previous most-chordal-suite (Suite II). But it is not the ultimate king of chords and double stops: the Sixth Suite has that honour ! See also “Chords and Double Stops in the Bach Suites“.