Tips and Tricks for Practicing Fast and/or Tricky Passages

In order to be able to play a “fast/tricky passage” we need to be able to do several things:

- play the entire passage slowly and with ease. If we can’t play a passage at a moderate speed with absolute ease, we will never be able to play it comfortably and securely at a fast speed.

- play each individual fast physical movement with ease. It’s only when we can coordinate easily each fast movement between any two consecutive notes that we can then start to hope to be able to link up and coordinate several or many fast movements. That’s why isolating and working individually on these different fast movements is a good preliminary step to working on fast playing in general.

To be able to play fast, we do need to practice fast, but this is perhaps the last phase of working up to fast passages. Practising slowly and with the utmost relaxation is one of the essential preparatory steps for successful fast playing but there are many other ways in which we can efficiently work on our fast passages. All benefit greatly from the use of a metronome. Let’s have a look at these different ways of working on our fast passages now:

GRADUALLY INCREASE THE SPEED

Play the passage as written, but slowly enough that it feels easy. Gradually increase the speed at which we play each repetition, making sure that it always feels easy. This is the most basic and natural way to gradually work a fast passage up to speed. But it can be a bit repetitive (boring) so we can also try some more imaginative (and efficient) alternative practice methods.

ELIMINATE READING DIFFICULTIES: READ AHEAD OR PLAY THE PASSAGE FROM MEMORY

Part of the problem of playing a fast passage can come simply from the reading aspect. Our eyes/brain can easily get left behind in fast tricky passages because they simply can’t keep up with the speed at which the information has to be processed. It is as though our eyes cannot keep up with our fingers.

When driving a car, running, skiing etc at high speed we normally need to be looking much further ahead than just the few metres that are directly in front of us. The faster we are going, the further ahead we need to be looking. The same principle applies to reading music. Especially for sight-reading and for reading fast hard busy and tricky passages in general, it helps very much to be reading the music well ahead of what we are actually playing (perhaps even as far ahead as possible). In other words, our eyes need to be always well in advance of what our hands are doing. This gives us time for mental preparation: we now know what we have to play before our hands actually need to do it, and we can thus anticipate the difficulties. This is another application of the ultra-fundamental “Anticipation Principle“.

It is an interesting idea to experiment with finding the upper limit of this concept: ¿how far ahead can I read this passage without it being so far ahead that I no longer remember what the hands have to play? We can try this with the passage at all different speeds, from slow to very fast. Possibly that the best way to get used to “reading ahead” is to practice reading as far ahead as possible but at slower tempos. We can also experiment with this “reading ahead” concept away from the cello, reading any written text aloud and experimenting with the eyes reading as far ahead of the voice as possible. The best way however to totally eliminate any possibility of reading problems disturbing our fast playing is to play the passage from memory!!

ADD SOME EXTRA BRAIN COMPLICATIONS AS A PRACTICE METHOD

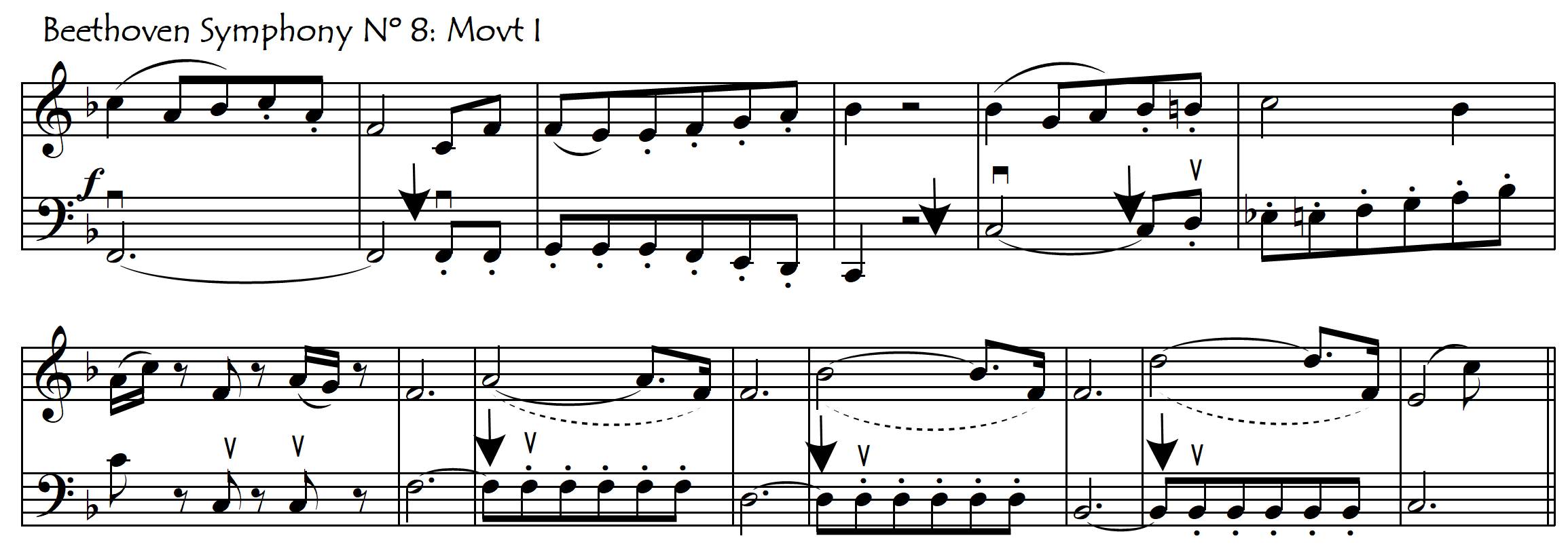

If we run with weights on our body, then when we remove those weights, running will feel so much easier. We can use a similar training method, but purely in the brain department. Counting aloud, singing the melody or accompaniment to our fast passage, tapping our foot or talking all add extra brain activity to our tricky passage, and when we remove that activity, the passage will seem easier. It is as though we suddenly have a lot more brain space available. Suddenly we are like a pianist who only needs to play now with one hand. In the following example, we can sing the top line while playing the lower line (or vice-versa). The arrows indicate bow retakes.

See also the following page: The Singing Cellist

PRACTICE WHILE WATCHING TELEVISION

Quite similar in effect to singing, talking, counting aloud etc, playing a fast/tricky passage while watching the television obliges us to be totally relaxed (otherwise we have no attention to give to the TV) and is a good way to test our assimilation and automatisation of a passage. The famous cello teacher Aldo Parisot used to recommend this practice method.

VARIANTS AND DEVIANTS

Practising the same tricky passage over and over in the same way is not only inefficient but also causes boredom. frustration, tension, OCD disorders, brain death, senility etc. Fortunately, other options are available, for example:

SEPARATE THE FAST MOVEMENTS THROUGH RHYTHMIC TRANSFORMATIONS

Here, we convert the passage into various exercises in which the fast movements are performed fast but are isolated from each other (distanced from one another) through rhythmic transformations.

1. DOTTED RHYTHMS

In the Basic Fast and Coordination page we use dotted rhythms to isolate individual rapid changes in order to be able to observe them better and to work on them more efficiently. Converting an entire passage into a dotted rhythm exercise allows us to alternate rapid movements (the ones after the short note) with less rapid movements (the ones after the long notes). If we then practice the same passage with the “reverse dotted rhythm” the “fast” movements are now the ones that were slow in the “normal dotted” exercise. Thus the two dotted variants complement each other.

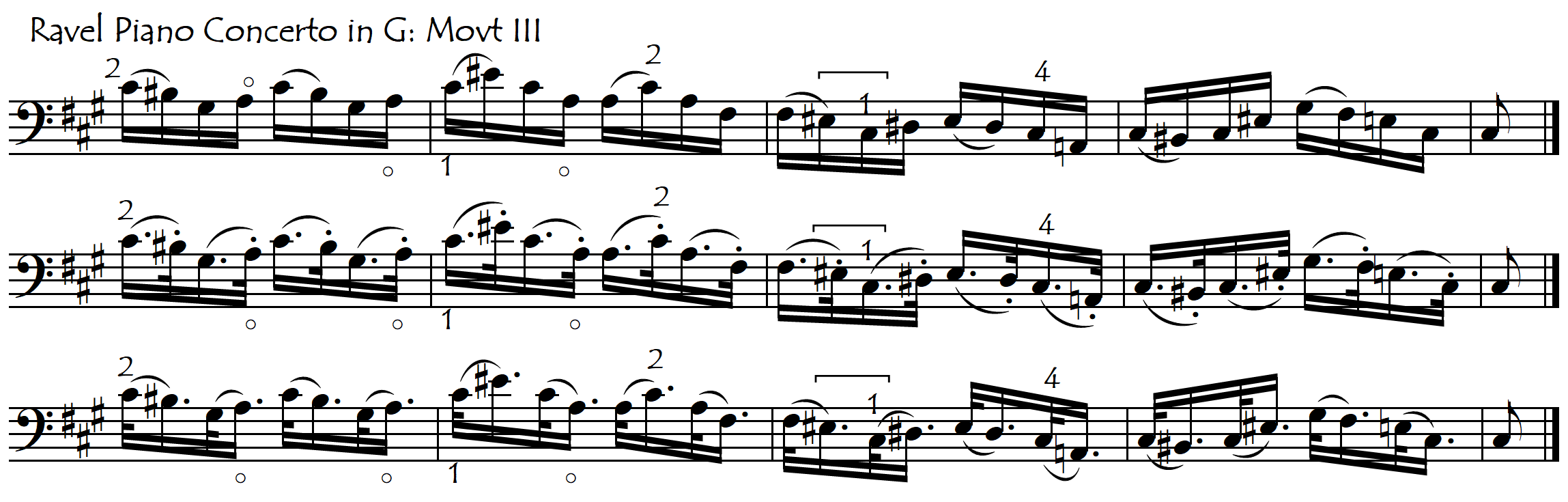

2: DOUBLE-NOTES

There is however another rhythmic variant by which we can isolate (separate) the fast movements from each other: practising the passage using several short fast repeated bows on each note. Here is the above Ravel excerpt presented now in double-notes as a practice technique.

In this way the movements we want to practice fast are still fast, but with the difference that now we have more time between these fast movements for our brain both to observe them and to recover its cool between them. Suddenly “the frenzy” becomes a controlled frenzy – which is actually no longer a frenzy. Only when our fast playing is not “frenzied” will it feel easy. This is our objective. We can play any fast passage, exercise or note sequence in this way. This is a very good way to work up to fast playing. Here below is a link to some fast repertoire excerpts in which each note (pitch) is played twice by the bow.

Fast Doublenote Passages: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

3. TRIPLE AND QUADRUPLE NOTES

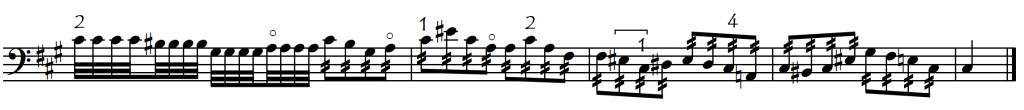

To isolate the note changes even more, we can use more (and faster) bows on each note. Instead of repeating each note twice, we could repeat it three or four times. This means that even though the left-hand spends more time on each note, we are making the changes between the notes faster. Repeating each note three times (triplet patterns) is not very useful for working on our fast passages because it adds the new coordination problem of the alternation of downbows and upbows on the beats, which is often an unnecessary complication, especially in passages with string crossings. But quadruplet patterns are very useful: we have no new upbow/downbow coordination problems, all changes are very fast (if we choose a fast tempo), but we have plenty of recovery time between each change of pitch. Here is the above Ravel excerpt, presented now in quadruple-notes (quads) as a practice technique.:

Here is a link to some fast repertoire excerpts in which each note (pitch) is played four times by the bow.

Fast Quadruplenote Passages: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

GROUPIES AND PACKETS

Without adding repetitions of individual notes we can break up longer fast passages into smaller groups of notes with pauses between the groups. In those little breaks between groups, our brain (and muscles) can catch up and relax/rest after each short burst of concentrated energy. We can choose the number of notes in each group according to the difficulty of the passage: the more difficult it is, the fewer notes we might want to put in each group, and by gradually increasing the number of notes in each “packet” we can increase the difficulty and test our mastery of the passage. In passages with binary groupings we may want to stay with multiples of two (2,4,6,8 etc notes in each “packet”), while in triplet passages we may want to stay with multiples of three (3,6,9, 12 etc):

Not only can we break up our problematic fast passages into these smaller groups. In some repertoire excerpts, the music is actually written in this way, with small groups of fast notes separated from each other. This can be very useful material for working on our fast-playing:

Different Sized Fast Packets: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

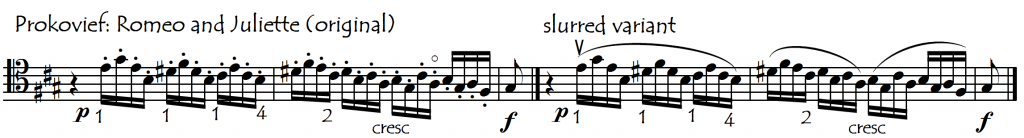

PRACTICE THE PASSAGE WITH DIFFERENT BOWINGS AND ARTICULATIONS

Slurred passages can be practised with separate bows and vice versa or we can mix slurs with separate bows. Mixed-bowing passages (such as the Ravel example above) can be played all-slurred or all-separate. We can also add and remove spiccato.

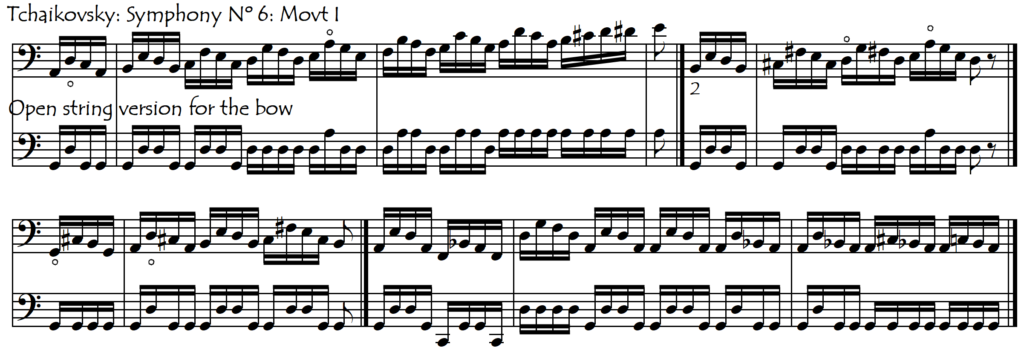

ISOLATE THE STRING CROSSINGS BY USING ONLY OPEN STRINGS

This will often require us to write out the passage in its open-string version. See also the String Crossings articles

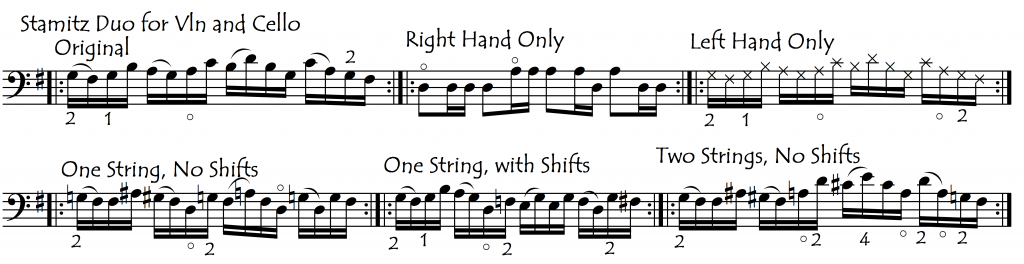

DISASSEMBLE THE MOTOR: CREATING PROGRESSIVE EXERCISES FROM ANY FAST REPERTOIRE EXCERPT

We can take any complex fast repertoire passage, take it apart into its different technical components, and then gradually reassemble it, progressively adding more and more difficulties. In this way not only are we learning the passage in an efficient way, but also we are using the passage to create exercises for working on each particular element of fast cello technique (finger articulation, shifting, string crossings etc). We can use absolutely any fast repertoire excerpt as our starting material.

Let’s look at how we might do this using a short musical example:

First, we will play it just using one hand ………. and then just using the other hand. Using only the right-hand means playing the entire passage on its corresponding open strings. Playing with only the left-hand means of course that there will be no sound (except for a few finger articulations).

Then we can play it on one string and in one position ………. then we can add, one by one the shifts or the string crossings, depending on which area is the most problematic (add the least problematic first).

Our choices of bowings are also important and can be varied to gradually add (or reduce) difficulty. Except for string crossing passages, it is usually simpler to play first slurred (with as many notes to the bow as comfortably possible). When we play fast passages with separate bows, we are adding the complication of Left-Hand/Right-Hand coordination. To increase the difficulty of a passage we can even invent complicated bowings mixing slurs, separate bows and spiccato articulations. Adding spiccato is the last ingredient we could add to this cocktail: it’s like the icing on the cake, the crowning glory etc …. The above passage has quite a fiddly (tricky) bowing. We can also practice it with other, simpler, bowings: