Left-Hand Finger Spacings

In the article on “Left-Hand Positional Sense” we looked at the ways in which we can “know” where our hand is on the fingerboard, and how we find our new hand locations. Here, on this page however, we will look at the somewhat different (and more refined) skill of knowing exactly how far away to place a new finger from a previous finger, after we have already established/located our correct hand position.

We talk in the above-mentioned article about the differences between Absolute and Relative Positional Sense. When we place our hand silently on the fingerboard we are normally using our Absolute Positional Sense to have an idea of where it is. In contrast to this, when we place one finger after another finger in the same basic hand position (i.e. without any shift) we use exclusively our skills of Relative Positional Sense. In other words, we place our new finger, according to the aural reference that our previous finger has given us.

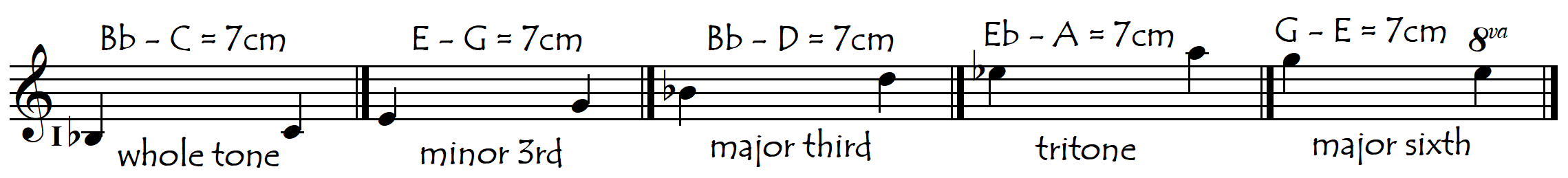

On keyboard instruments, the notes are all equally spaced over the entire range of the instrument, meaning that the physical distances between the fingers do not change as the hand goes up and down in pitch. On string instruments however, those physical distances between the notes become smaller as we go higher up each string. For example, on the cello, the one-tone interval in the first position (for example between Bb and C in first position on the A-string) is produced by a finger spacing of approximately 7cm. But that same 7cm distance represents a progressively larger (wider) musical interval as we move it up the fingerboard. The following musical intervals are those that are sounded when we place our lowest finger on different notes (on the A-string) and reach up 7cm to a higher finger. This distance will be less than 7cm on smaller cellos, and greater on cellos with a longer string-length.

Curiously, whereas we constantly use the first and second fingers to stretch (play) the 7cm whole-tone interval in the extended “first position”, we very rarely use that same stretch in the higher positions.

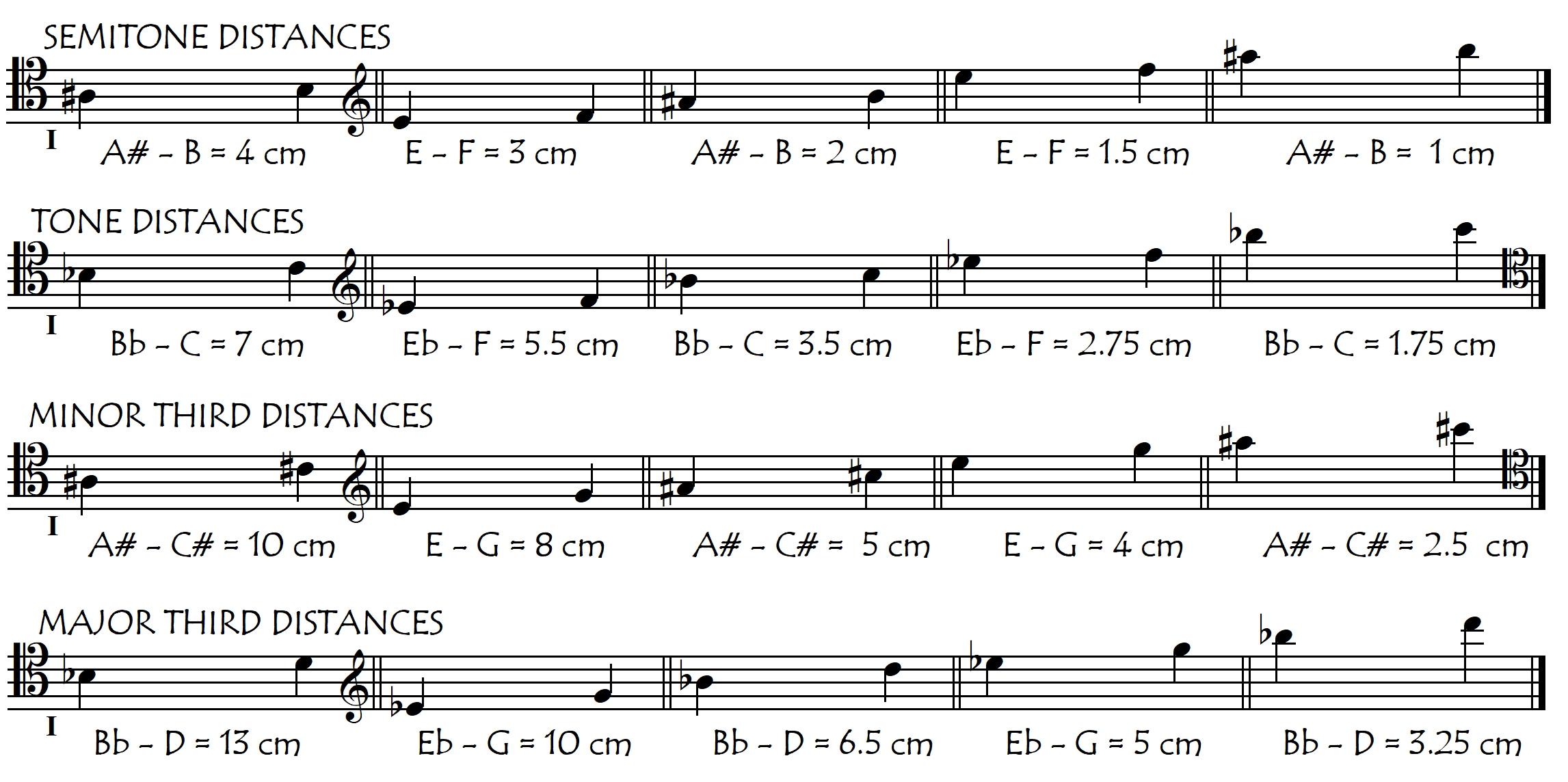

In the above examples, we see that the same finger-spacing (distance between fingers) produces gradually increasing musical intervals as we move up the fingerboard. To illustrate this same phenomenon but from a different perspective let’s measure now the finger-spacing distances required to give some of the common intervals between the fingers in different parts of the fingerboard.

It’s funny how the same interval, when played one octave higher up the fingerboard, requires exactly half the distance as it did in the lower octave. Pythagoras discovered this (and a lot more) approximately 2500 years ago, but it’s never too late to (re)discover it for ourselves while fooling around at the instrument …….

This is totally unlike the piano and all other keyboard instruments. For the keyboard player, the 12 notes of every octave on their instrument are always the same distance apart, no matter in what register they are played. On the cello, by contrast, the distance required to make a semitone interval varies from a maximum of 4cm in first position to less than 1 cm in the stratosphere. Each and every one of the seven octaves on the piano requires exactly the same hand span (approximately 17cm) whereas on the cello the first octave measures 33cm and each subsequent octave is half the distance of the previous one.

The fact that the physical distance of each musical interval on string instruments is so influenced by how high up the fingerboard our hand is makes string instruments very “un-mechanical” …… which is one of the reasons why it is hard to play our instruments “in tune” and why we need to practice so much!