Advantages of Thumbposition

This page, part of the large section devoted to thumbposition, is actually longer than the page dedicated to “problems of thumposition“. Well this is not surprising ………. because if the difficulties of using the thumb outweighed the advantages then we just wouldn’t use it!

The thumb is undoubtedly the most useful finger in the higher (Intermediate and Thumb) regions. Let’s look at the reasons for this:

1: ERGONOMIC COMFORT

As we climb the fingerboard, the decreasing distances between the notes mean that the placing of the thumb on the fingerboard becomes increasingly comfortable and no longer creates contortions and tension in the hand. This is very fortunate as it compensates for the fact that the fourth finger becomes rapidly useless (it’s simply too short) at more or less the same moment that the use of the thumb becomes comfortable (i.e as we leave the neck positions behind).

2: STOPPING THE STRINGS FOR THE OTHER FINGERS

When the thumb is pressing the string down (“stopping” it), the other fingers don’t need to work so hard, either to articulate the new notes or to maintain each note. The thumb is doing half of their job for them. This is fortunate because string height is usually at its greatest in the higher fingerboard regions, and the thumb, with it’s great strength (and perpendicular orientation to the fingerboard), is perfectly suited to holding the strings down.

3: FIFTHS

This enormous strength of the thumb and its perpendicularity to the fingerboard make it also ideal for playing fifths. The thumb acts almost like a guitarists “capo” but, unlike the guitarist’s accessory, the cellist’s thumb is instantly movable. The thumb is the only finger that can be used to easily and naturally (ergonomically) play “capo fifths” (with one finger stopping the two strings simultaneously) in the higher regions (unlike in the Neck Region).

4: ALL NOTES OF THE SCALE NOW UNDER THE HAND

What’s more, we now, like violinists, have all the notes of the scale under our fingers. Without the thumb, a one-octave scale with no open strings requires two shifts. With the thumb it requires none. Now we can play a truly legato scale across the strings, in any key, without having to do any big stretches or hide any fast shifts across the string crossings.

5: TRANSPOSABILITY

Because we have all the notes of the scale under the hand (and because we no longer use open strings), in thumb position it no longer matters what key the music is in. The thumb plays the same role as the open strings in neck position (or a guitar “capo”) but with the added advantage that it can be moved around with enormous ease. We can change key now without having to change our fingerings. If we can play a thumb position passage in one key, then we can do it equally well in any other (neighbouring) key, bearing in mind of course that the lower we go, the more difficult the hand position becomes because of the increasing distances between the notes.

6: VISUAL POSITIONAL REFERENCE

The thumb, because of its very clear position perpendicular to the strings, gives us a good visual reference as to where we are on the fingerboard. We need to develop this visual positional sense because as soon as we put the thumb up on the fingerboard, we are desperately lacking in other types of positional references .

7: EASY AND ENORMOUS EXTENSIONS BETWEEN THUMB AND FINGERS

Another advantage of thumbposition, is the extreme ease with which we can open and close the gap between the fingers and the thumb. This has several very useful consequences:

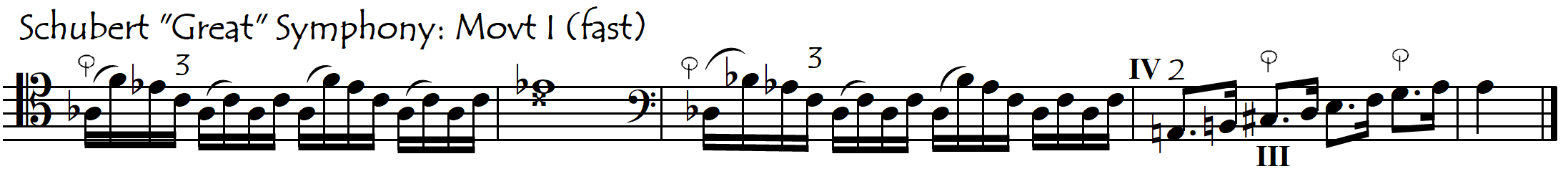

- By using the thumb, the strained 1-3/4 major third extension can be substituted by the effortless T–2 or T-3 fingering (where T indicates the thumb). This is especially useful for small-handed cellists. In fact, small-handed cellists have even more reason than large cellists to really train their thumbs well, because of this functionality as an “extension-avoider”. This is useful not only “up high” but also in the Intermediate Region (and even sometimes in the Neck Region), where the distances between fingers are larger. The following exercise can be transposed all over the cello:

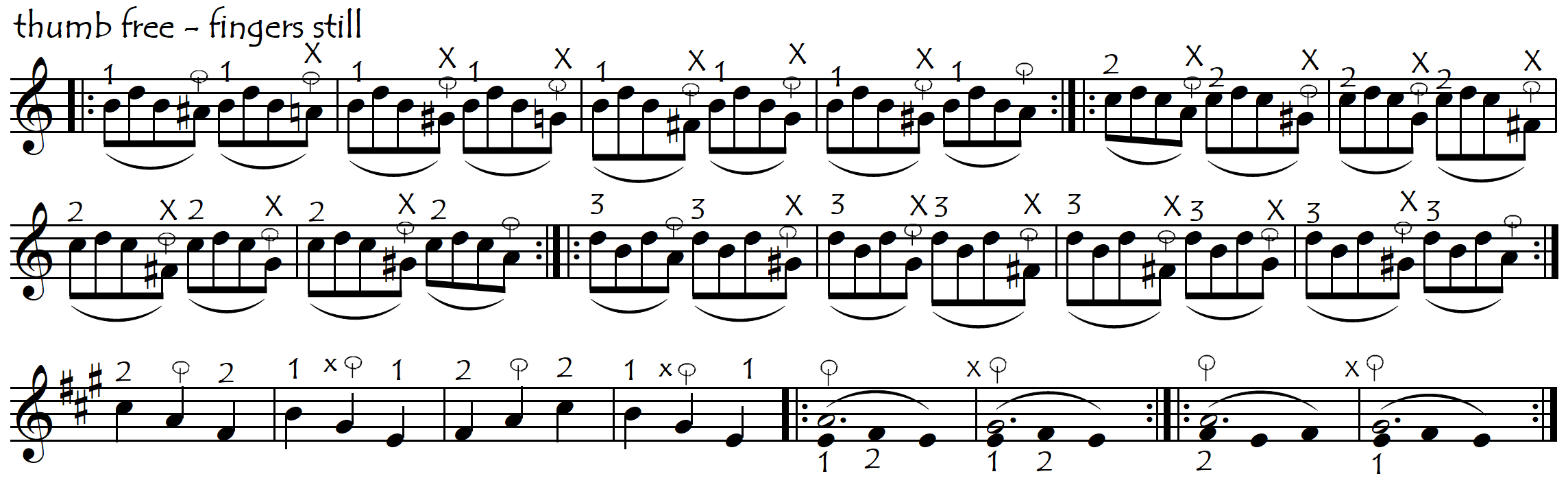

Small-handed cellists might prefer to use the thumb in the Neck Region to avoid prolonged strained extended passages. We may need to keep another finger down during long held thumb notes in order to be able to do vibrato on the thumb. The “x” note in the following passage indicates this silently held finger.

- The thumb can move down away from (and up towards) the “fixed” fingers and likewise, the fingers can move up away from (and down towards) the “fixed” thumb. We will call these movements Non-Whole-Hand movements (abbreviated as NWH movts) because one part of the hand always remains still (“fixed”) while the other part of the hand moves. In the first examples the thumb is the steady unmoving anchor while the fingers move freely up and down the fingerboard:

In these next examples it is the thumb that moves freely while the fingers stay in the same position:

This anatomical ability of the hand to effortlessly extend and contract the space between between thumb and fingers opens up a whole new world of fingering possibilities that are only available to us in thumb position. Using these NWH movements to get around in Thumbposition can be especially advantageous in situations in which we can’t use an audible glissando to hear our shift, because that part of the hand that remains still (“fixed”) provides us with a stable positional reference that we would lose if we were to shift with the whole hand-arm. “Crawling“, in which we alternate extensions and contractions, allows us to move around the fingerboard using snake-like movements in which we are never without a stable reference point. When we do crawling (also called “snaking”) this reference point is simply changing constantly, alternating between the thumb and the fingers as in the following example:

This subject is dealt with in much greater detail on its own dedicated page:

Non-Whole Hand Movements in Thumbposition

The higher up the fingerboard we go, the greater the possibilities for non-whole-hand movements become because the distances between the notes grow smaller.

This extraordinary freedom of the thumb in relation to the rest of the hand gives us enormous advantages, but it also creates some complications. If the thumb was always “attached” to the hand at the same constant interval behind the first finger (like a trailer attached to a car) then we would never have to worry about its choreography. But because this distance can be so easily varied, in all “non-standard” distances between the thumb and the fingers, we need to be very aware where it (the thumb) is in relation to the other fingers (especially with relation to the first finger). In “Non Whole Hand” movements this awareness is not so complicated (because there is always one part of the hand that is “still” or “fixed”), giving us our “home base”. But when we need to do these “Non-Whole-Hand” movements during a shift we enter into a new, higher level of complication. This is more complex, dangerous terrain. Compare the following examples: