Left Hand Vertical Positional Sense IV: AURAL SENSE

This article is part of a larger article dedicated to Left Hand Vertical Positional Sense in general.

What do string players have in common with bats and sharks …… we also locate our target principally with our ears (hearing). Whereas our eyes are our principal navigational aid on earth, it is our ears that give us our ultimate definitive feedback as to where our hand is on the fingerboard.

Before we actually sound a note, our positional senses (kinesthetic, tactile and visual) tell us approximately where we need to put our finger down. But even under the best conditions and with the most talented players, our positional senses are not 100% accurate. It is only when we have actually sounded a note, that we finally know, definitively and exactly, where we are. Hearing a note, not only allows us to correct its intonation (fine-tune the positioning), but also gives us an absolutely clear, defined reference from which to find the other fingers in the same hand position (the notes that “lie under the hand”) and also gives us a reference from which we can locate other nearby positions. But how do we find that very first note ?

“FIRST NOTES”

When a note is preceded by a silence we have the luxury of being able to do a quick sound-check on it before we actually play it. Even though we are calling these types of notes “first notes”, this concerns in fact any notes that we can sound (secretly) before we play them. We use the word “secretly” because the whole idea is that this “pre-sounding” of the note should be inaudible for the public but sufficiently loud that we, the player, can hear where our finger is and correct the intonation before we actually play the note in its musical context. In other words, we are checking the note we are about to play, before we actually play it. This is by far the easiest way to find notes accurately on the fingerboard. If only every note could be comfortably checked and corrected before we start playing it !!

There are two principal ways to sound a note before we play it: we can do either a quiet left-hand pizzicato (with a higher finger), or simply articulate the stopped finger just hard enough to sound the note. These two techniques are extraordinarily useful “tricks of the trade”. Often in Thumb Position, rather than sounding our starting finger, we will sound the thumb with a light left-hand pizzicato of a higher finger and use the thumb as our reference point from which we then place the starting finger.

Normally a “starting note” comes after a silence. But sometimes we can use this technique during an open string or during the resonance of the preceding note.

THE USE OF GLISSANDI:

In the same way that a tightrope-walker never loses contact between his feet and the rope, it is very useful for us to maintain as much as possible the contact between the left-hand and the cello, as this tactile contact gives us so much vital information about where we are on the fingerboard. Even a silent glissando is a great positional help, but when we can actually hear our glissando, then there is no better type of positional feedback.

GLISSANDI IN SHIFTING

Using audible glissandi to connect the start and destination notes provides a huge, invaluable help for our positional accuracy. An audible glissando during a shift gives us constant feedback about where we are and allows us an easy, controlled “landing” at the destination note with complete intonation control. However, that same audible glissando can later be made inaudible to the listeners through the careful use of bow pressure (reduction of bow pressure during the shift). This means that there need be no contradiction between technical and musical requirements: the left-hand slides around with almost continuous contact with the strings but it is the right arm that determines whether or not (and how much) they are heard.

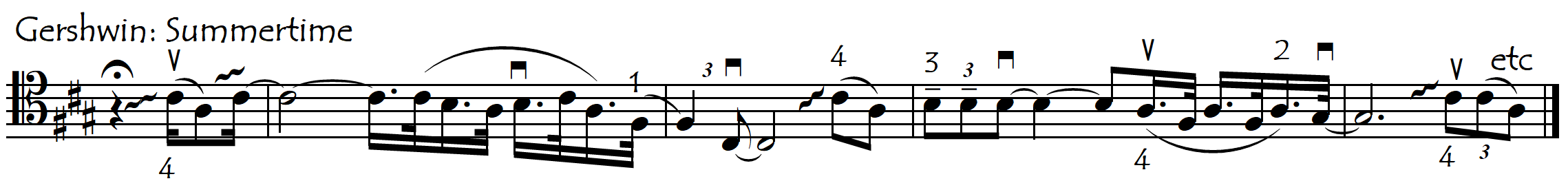

When we practice our shifts with audible glissandi, we are programming the brain and body with this aural measurement of distances so that even when we do the same shift silently (without any audible glissando), we still imagine the sound of the glissando and use this mechanism to measure (evaluate, judge) the shift distance. In the following example if we first learn the passage with audible glissandi, then we can play it easily also in another musical context in which there is no possibility of hearing the glissandi.

In the above examples – unlike in the example below – we can maintain the contact of our finger(s) with the string during the shift, which means that we don’t lose either our vertical or horizontal positional references during the shift. We can therefore now find the target notes not only by “knowing” their absolute positional location but also by measuring (feeling, sensing) their distance from the previous note. This measuring of distances is much much harder when we lose the contact of the fingers with the string. Thus, thanks to the constant finger/string contact we can use simultaneously both our “relative” positional sense and the “absolute” positional sense that we normally use when finding a note from the air. Certainly, for smaller intervals, this is much easier than just finding the notes “from the air” because when we keep finger/string contact during the shift, we have not only the spatial reference of the thumb-neck contact but also have the references (spatial and aural) of the previous note. Compare the above example with the original Schumann repertoire excerpt below:

In this passage we have to find the notes “from the air” because each “fingered” note comes right after the (same) open string. It is not possible to maintain the finger-string contact. The need to remove the fingers to allow the open string to sound means that we don’t have the possibility of using any glissando (neither audible nor inaudible-but-imagined) to find our new position. This is a classic example of “Absolute Positional Sense“. Not only do we have to get the pitch right (“vertical” positional sense) but we also have to land perfectly centred on the correct string (“horizontal” positional sense – see Left Hand String Crossings). This is not easy. We could call this also the “Airdrop” technique and we need it not just after an open string but also after natural harmonics (on the same string).

Finding a note accurately like this, without any previous left-hand aural feedback to orientate us, is difficult, as it depends mainly on our “absolute” positional sense, less precise and less easily controlled than our aural “relative” sense.

GLISSANDI FOR FINDING FIRST NOTES

Glissandi are not only useful for shifting but can also be used for the safe finding of “first notes”. Sometimes – especially in “popular” musical styles – rather than our private little left-hand-pizzicato preview of a starting note, we might prefer to find the note using the vocal technique of sliding up into it. This can be a very expressive way to start a note and can be made almost inedible by careful left-hand timing and dosage (calibration) of bow pressure.