Fast, Multi-Finger, and Mixed-Hands Cello Pizzicato

In slow pizzicatos, we are concerned with the sound quality of each individual note. In faster pizzicatos, however, by definition, our problems are quite different and mostly concern speed, coordination and accuracy (plucking the correct string at the correct time). The use of occasional left-hand pizzicatos interspersed amongst the right-hand pizzicatos is one of the “tricks” that we can use to be able to play all of the notes but there are many others. On this page, we will look at these many ways in which we can facilitate our fast pizzicatos.

DIVISI (DIVEASY) AS A SOLUTION FOR ALL FAST ORCHESTRAL PIZZICATOS

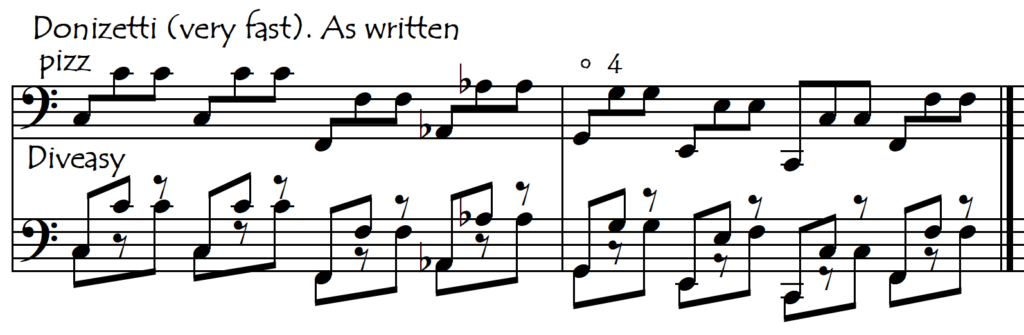

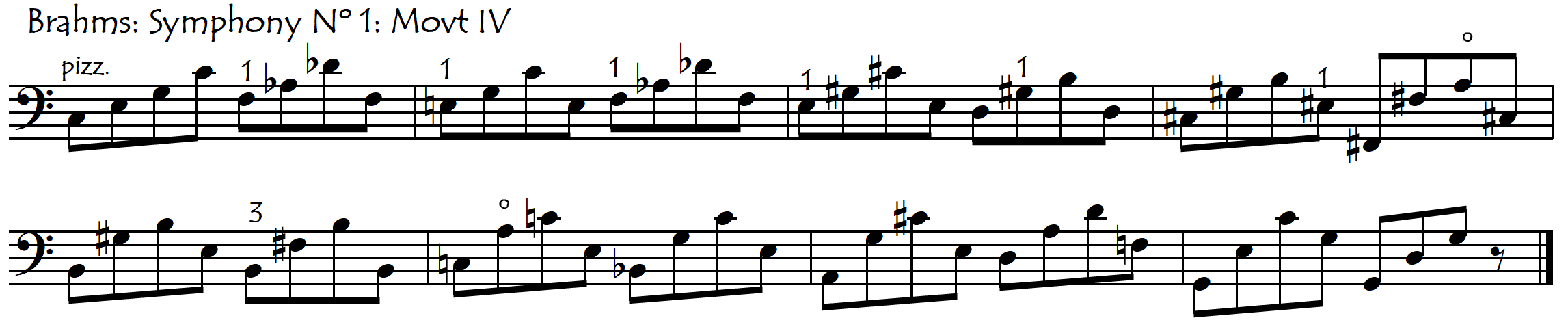

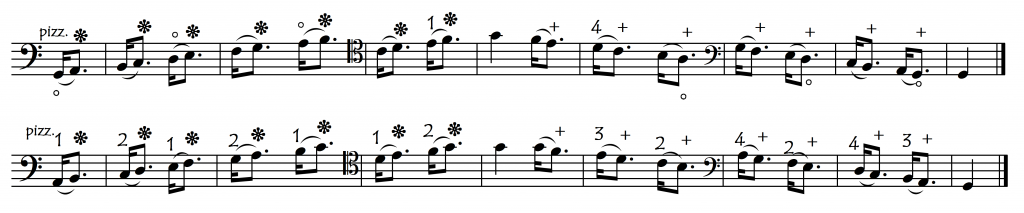

Many fast pizzicato passages are only possible in the composer’s head (or at the keyboard). They notate their fast pizzicato passages simply as they sound and leave it to the players to work out how to play them. If we are more than one cellist playing a fast pizzicato sequence, we can easily eliminate all of the speed-induced difficulties by playing the passage “divisi”. With a simple note redistribution (sharing of the load), even the fastest, most awkward pizzicato passages can be made easy as in the following excerpt from Donizetti’s opera “Don Pasquale”:

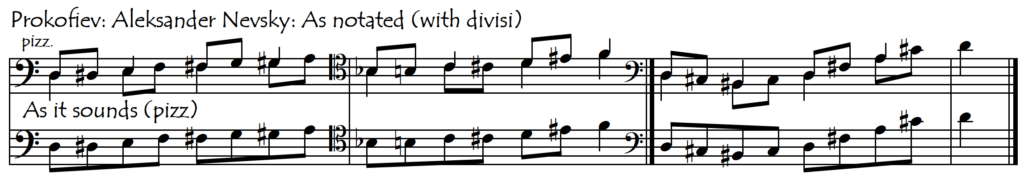

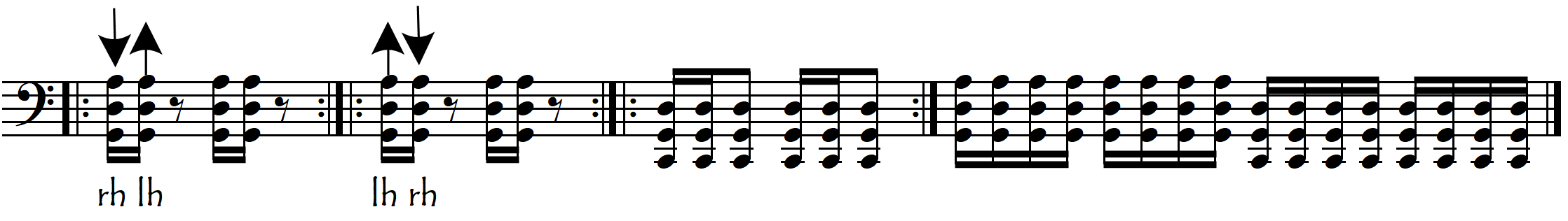

Prokofiev is one of the few composers who understood this possibility and he often notates his fast pizzicato passages with the divisi incorporated into the notation. This looks complicated, but once we have studied the passage carefully the end result of the divisi is much more secure and much easier to play than if each cellist tries to play all of the notes:

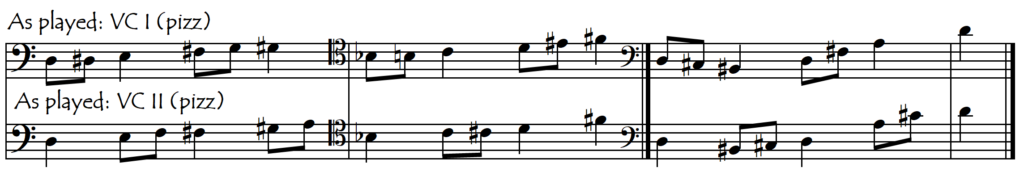

Prokofiev’s divisi notation is one large step towards making our job easier. Another step in player-friendliness would be to actually notate the divisi on two staves, thus making it much easier to read:

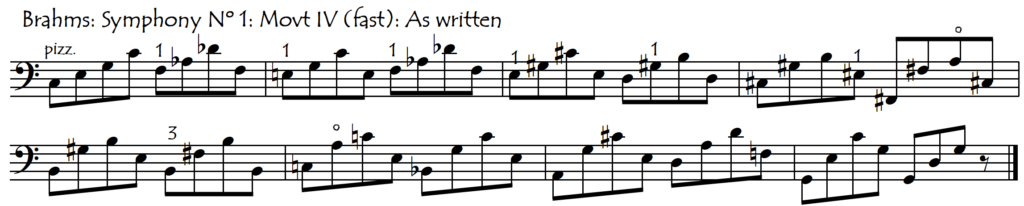

Unlike Prokofiev, most other composers are/were unaware of the possibility of divisi and notate their fast pizzicato passages simply as they sound. This means that, if we want to avoid the tension, stress, and insecurity of the fast pizzicatos, we will need to use our intelligence to work out how best to divide the notes between the players.

This passage could be played with the following divisi. Unfortunately, it is difficult (and probably ugly and confusing) to try and notate this in the existing part, so we will just have to remember who plays what:

If we are the only cellist playing our fast pizzicato passage, then we do not have the possibility of using divisi to avoid the difficulties. Let’s look now at some of the ways (techniques, tricks) by which we can make solo fast pizzicato passages playable and even easy.

THE IMPORTANCE OF A STABLE POINT OF CONTACT REFERENCE/ANCHOR FOR THE RIGHT HAND/ARM

Trying to pluck the strings from a free-floating right-arm is a recipe for insecurity. For isolated pizzicato notes, or in slower pizzicato passages, it is our preparatory contact of the plucking finger with the string that gives us our positional security. In other words, if we have time to comfortably touch/find the string with our plucking finger before we pluck it, then this contact is perfectly sufficient to give us (right hand) positional security. However, in faster pizzicato passages in which by definition we don’t have time to make this preparatory contact, our right hand can easily become “lost in space” and we may therefore find ourselves plucking the wrong string, or two strings at once, especially in passages with many changes of strings. How can we avoid this?

THE USE OF THE THUMB AS A STABILISER AND POSITIONAL REFERENCE

Try the pizzicato passage from Brahms’s First Symphony that we used as an example above, but this time playing all the notes (without divisi):

A tightrope walker never loses contact with the high-wire. Likewise, in faster pizzicato passages it can be very helpful, for our right hand’s positional security, to maintain the thumb in permanent contact with the right edge of the fingerboard. This gives us simultaneously a fixed spatial reference as well as a stable anchor point. In other words, even though we may not use the thumb to pluck the strings in fast passages, it can nevertheless be vitally important in their smooth execution, thanks to this stabilising and security-giving contact with the fingerboard. As mentioned above, this is especially useful in faster pizzicatos because here, by definition, we don’t have the time to prepare the finger-string contact before each pluck. If we just let the arm float in the air (without this thumb contact), then we have no secure spatial reference. Without this “contact point”, it is hard to sense (feel) exactly where the right hand and fingers are in relation to the strings.

WHEN TO GLUE THE THUMB AND WHEN TO RELEASE IT?

Doing pizzicatos while having the thumb glued to the fingerboard edge is less visually interesting (expressive) than when the hand and arm are free to move. It feels mechanical, dry and restricted as we can have neither a beautiful approach to string nor a beautiful follow-through after the note. This is why we only use this technique in faster pizzicatos, where the need for technical security, control and stability is primordial. Whenever we have enough time before and/or after the notes, we can once again release the thumb and allow the arm/hand to move freely and expressively as in the following examples from Shostakovich’s Piano Trio Op 67 where the curved arrow represents the follow-through that we can do when we have time before the next pizz:

AN ALTERNATIVE TO THE FIXED-THUMB ANCHOR POINT

Having the thumb glued to the edge of the fingerboard in faster pizzicato passages reduces our right-hand’s range of movement considerably. To avoid this, we could release the thumb and choose instead to have the right forearm touching the edge of the cello’s belly as an alternative means to achieve this necessary function of positional sense and stability. This frees up our right hand somewhat, allowing both hand and wrist a greater range of movement. Try the Brahms Symphony excerpt in this way also, as well as the following page of fast pizzicato repertoire excerpts.

Fast Pizzicato: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

The third movement of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony is all fast pizzicato. For a very practical “study” in fast pizzicatos, we can download the cello part from imslp.org and play along with a recording.

As with so many elements of cello playing (and life), for each different situation, we need to balance the contrasting needs for “security and reliability” on the one hand with “freedom and expressiveness” on the other. Some people have a better sense of where their body parts are (kinesthetic sense) than others. Those lucky ones will have less need to maintain the thumb-fingerboard contact.

MULTI-FINGER CHOREOGRAPHY

Guitarists (and bass players) would probably laugh at us cellists when they see how often we get tangled up in knots while struggling to play fast pizzicato passages with only one finger. Guitarists have many tricks to help them choreograph (play) fast plucked passages. Most of these “tricks” involve using more than one finger. Trying to do fast pizzicatos with only one finger is like trying to run fast with only one leg: a hopping race. There are multiple possibilities for using more than one finger in faster pizzicato passages:

1: THUMB-FINGER COMBINATIONS IN STRING CROSSINGS

Pizzicato passages with leaps across strings show us one of the most simple ways to use two fingers: making use of the thumb on the lower string(s) while we use our normal pizz finger on the higher string. Because the thumb plucks the string in the opposite direction to the fingers, we can set up a very rapid alternating hand oscillation that uses both directions to pluck the notes. This can go much faster than anything we could ever do with one single finger alone. With the finger and thumb, we can now run.

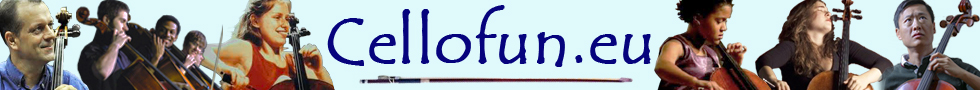

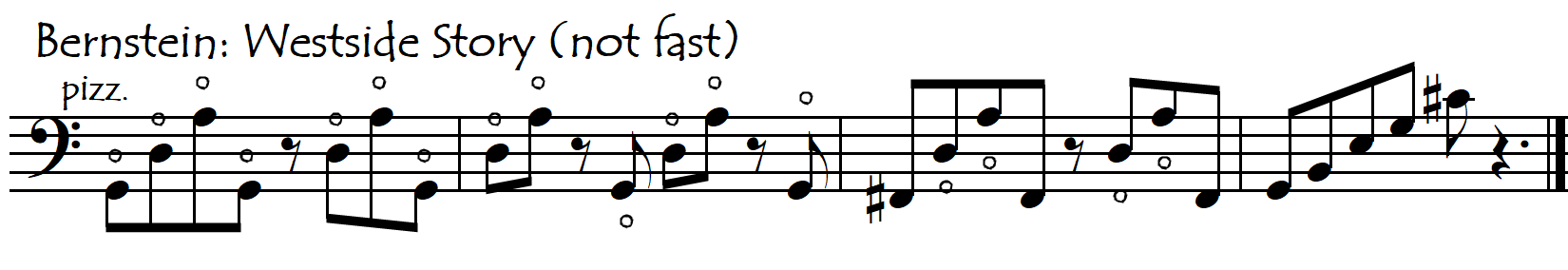

In the following examples of this use of the thumb as well as another finger, the arrows indicate the direction of the pizz movement. “F” means “pizz with a finger” and the inverted thumb symbol means “pizz with the thumb” :

The thumb/finger combination is also useful in dotted-rhythm figures, especially (but not exclusively) when the two notes of the figure are on different strings. In the following examples both situations are present:

2: SLOW MOTION GUITAR STRUM TECHNIQUE FOR BROKEN CHORDS

In broken chords, we can sometimes play several notes consecutively with the same pizzicato movement. This is like a slow guitar strum, the pizzicato equivalent of a slur with the bow. This, in faster playing, is much easier than trying to pluck each note individually with a separate impulse. The inverted thumb sign means “pizz with the thumb” while “F” means “pizz with the finger” .

Here is some practice material for working on these alternations between the use of the thumb and the finger for the pizzicato plucks:

Alternation Between Thumb And Finger in Pizzicatos On Different Strings: EXERCISES

Alternation Between Thumb And Finger in Pizzicatos On Different Strings: STUDY

Alternation Between Thumb And Finger in Pizzicatos On Different Strings: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

3: MULTIPLE FINGER PIZZICATOS IN FASTER PASSAGES (NO STRING-CROSSING OSCILLATIONS)

In faster passages that don’t have string crossing oscillations, we may find it easier to use only the fingers (and not the thumb) to pluck with. We can (like guitarists) develop the skill of playing with two (or more) fingers to make fast-playing easier. This does not come easily, so we need to develop it progressively. Here below are some amusing coordination exercises. Use different combinations of plucking fingers (for example: 1-2, 2-1, 1-2-3, 3-2-1 etc) and finish off by playing simple scales with different combinations of plucking fingers.

***************************************************************************

MIXED-HAND PIZZICATOS

Not only can we make use of other fingers of our right-hand to facilitate faster pizzicato passages. We can also very often make use of occasional left-hand pizzicatos in passages where our right hand just doesn’t have time to comfortably play all of the pizzicato notes. Even though most composers just write “pizz” for any pizzicato passage, it is surprising how often we can use our judgment and intelligence to find ways to make some complex or rapid pizz passages easier by giving some of the notes to the left hand. It might be a good idea to read the article dedicated to left-hand pizzicatos before continuing, as it describes in detail the two types of LH pizz: the standard “pluck” (indicated by a + symbol) but also the percussive “whack” (indicated by the snowflake * symbol). Let’s look now at some of the different situations in which we can make use of LH pizzicatos during a “normal” pizzicato passage:

1. LEFT-HAND PLUCK OF AN OPEN STRING TO FACILITATE RAPID CHANGES BETWEEN PIZZ AND BOWED PASSAGES

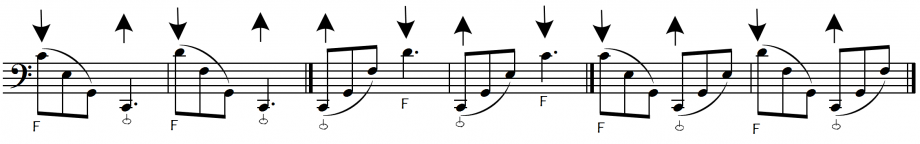

A very useful benefit of LH open-string pizzicato is in facilitating rapid changes between arco and standard right-hand pizz. If the first pizz note after a bowed note – or the last pizz note before a bowed note – is an open string, then we can pluck that open string with a left-hand finger in order to give the right hand more time to comfortably make the change between arco and pizz, as in the following examples:

Sometimes, these changes from arco to pizz via L.H. pizzicatos can involve quite complicated “choreography” of the two hands.

2: LEFT-HAND PLUCK OF AN OPEN STRING FOR OTHER REASONS

Rapid strumming of open string chords can be done with an alternation of the hands. The left-hand strum will always be in the upwards direction (from lower to higher strings) unless we deliberately want to have the sound of the reverse-pluck with the fingernails.

And sometimes we might use an LH pizz of an open string during a normal pizzicato passage not because we absolutely need to, but rather because it is fun, giving a nice choreographic, dancing body language to the passage, a little like a “pas-de-deux” for the two hands:

3. OCCASIONAL LEFT-HAND PIZZ IN FAST PIZZICATO PASSAGES TO AVOID IMPOSSIBLY RAPID PLUCKING

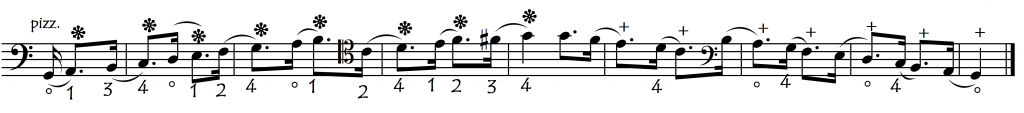

Sometimes, the right hand simply cannot pluck fast enough to play all of the notes comfortably. The use of LH pizzicatos on occasional notes to give the right hand a rest in fast pizzicato passages can be real life-saver. Before looking at extended fast passages let’s isolate some of the fast movements by using dotted rhythms (see Fast Playing). How could we pizz the following passage at a fast speed?

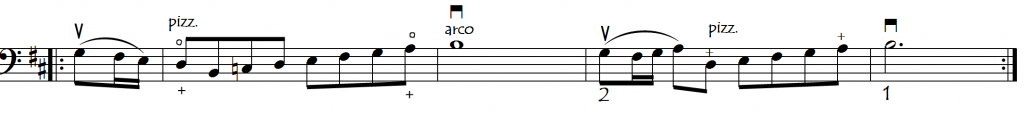

Using only right-hand pizzicatos, it is extremely difficult (or impossible) to play this passage fast. By interspersing a few left-hand pizzicatos however, we can make this passage not only playable but even easy. In this passage we will make use of three different types of LH pizzicatos:

- where a higher finger is articulated so fast and so forcefully after a lower finger (or after an open string) that the note sounds almost as strongly as if we had plucked it (indicated in the following examples by a red circle or oval). We could call this technique the “whack”. Guitarists use this technique very often, usually in fast playing.

- where the preceding (higher) finger plucks a lower finger (red rectangle)

- where the preceding playing finger plucks the same open string (green rectangle)

The use of slurs and + signs can be useful to help us remember how to “choreograph” these complex mixed-hand pizzicato passages. The first note of any pizzicato slur will be plucked with the right hand, while the next note under the slur is sounded either by a “whack” (ascending progression) or by a LH pizz (descending progression). In the above example, the “+” sign is ambiguous because it indicates both LH pizz and the “whack” technique. Perhaps we could use two different signs to indicate these two very different techniques: “+” for a LH pizz and “*” to indicate a “whack”, as shown in the following rendition of the previous example:

Composers don’t normally know anything about LH pizz, let alone about its different types so of course, it is the cellist who has to “edit” the part by adding the slurs and the + or * signs.

Before looking at “real” fast passages (with continuous fast notes), let’s look at some more variations of these same dotted rhythms. Here, the dotted rhythm allows us to isolate the different fast movements:

And, to finish with these dotted rhythm examples, let’s return to the repertoire passage with which we started this article, in which normal right-hand pizzicatos are interspersed with left-hand plucks and whacks:

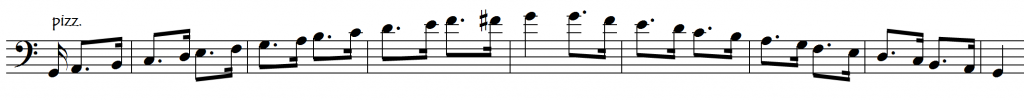

Now we can try some more continuous rapid passages. Here the alternation between LH and RH pizzicatos is faster, with less resting time in between, and the coordination and choreography problems increase:

The “Scherzo Pizzicato” movement of Benjamin Britten’s Cello Sonata in C Op 96 uses just about all these Left-Hand (and Mixed-Hands) pizzicato effects and, apart from being real music, is also one of the best studies imaginable for acquiring and perfecting these skills.

We can even do our left-hand pizzicato whacks after a shift, as in bars 3 and 5 of the following example:

Mixed Hands Pizzicato: EXERCISES Mixed Hands Pizzicato: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS