Study Material for Dotted Rhythms

On this page can be found ideas, repertoire excerpts, studies, and exercises, for working on different types of dotted rhythm problems. As a general rule, for working on rhythms – and especially for dotted rhythms – the use of a metronome is an absolute necessity. The observation that humans tend to shorten the long notes in dotted figures would almost have the category of a natural law. It seems almost as though we are trying (unconsciously) to restore balance, symmetry and equilibrium (and relaxation) to a rhythm that is deliberately unbalanced and asymmetrical. This is perhaps why the jazz/pop “triplet” dot is so much easier than the tighter classical “quad” dot and it is because of this relative ease that we will start with these triplet dotted figures.

After the triplet dot, the next phase in increasing difficulty is compound-time dotting, followed by binary dotting. To make everything more difficult and tighter we can do each of these with double-dotting, in which the short-note length is halved.

Although at the bottom of this page you will find repertoire compilations of dotted passages, we can initially just “fool around” with absolutely any note patterns – improvisations, figures in one position, scales, arpeggios, string crossing passages etc – using the standard triplet, compound and binary dotted rhythms shown below. We should however probably keep the notes simple if we really want to work on the rhythm and our bow control.

TRIPLET DOTTED RHYTHMS

Triplet dotted rhythms refer to the laid-back ternary dotting style used so much in jazz and pop, in which the short note is one-half of the length of the long note. This is longer than in “normal” classical binary dotted figures, in which the short note is only one-third of the length of the long note. To say the same thing but with other words, in standard triplet dotting, the long note is twice the length of the short note, whereas in “classical” dotting it is three times the length of the short note.

Triplet dotted rhythm figures (𝅘𝅥 𝅘𝅥𝅮) are thus more relaxed (less intensely dotted) than quadruplet (𝅘𝅥. 𝅘𝅥𝅮) figures and we have to be careful in a lot of classical music (in contrast to pop, swing, jazz etc) to “not let our quads become tripe”. Or, in other words, to keep our dotted rhythms crisp and tight (quadrupletised), not letting them relax into laid-back triplets. A piece to play to work on this potential problem is the Courante from Bach’s D minor Partita for solo violin, in which the alternation of triplet quavers with dotted quaver/semiquaver figures is constant.

COMPOUND-TIME DOTTED RHYTHMS (3/8, 6/8, 9/8 etc)

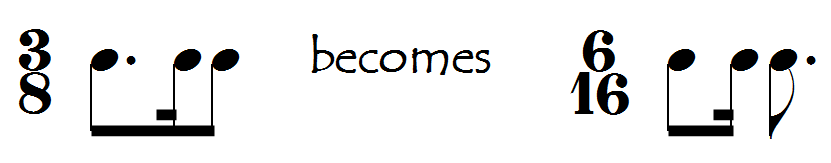

These make a good second phase for our dotted rhythm work because, although the dotted figure is now “tight” (quadruplet and not triplet dot), in compound time usually we have two longer notes for each short note, therefore we have more “recovery time”. In other words, we have more time to observe what is going on both before and after the short note. Let’s start with the most common compound-time dotted rhythm figure:

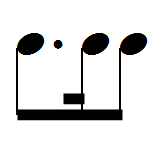

One of the most common dangers with this rhythm, especially in faster passages (where each triplet figure is one pulse and not three), is that it can easily and inadvertently mutate into a more comfortable, lazier version in which our three eighth-notes become two dotted quarter-notes while at the same time, our dotted rhythm becomes a laid-back triplet dot rather than the tight classical quadruplet dot:

This is a very good rhythm to use to practise scales, arpeggios etc and serves as a good example of how useful it can be to choose our scale fingerings according to the rhythm, rather than just using standard scale fingerings according to the key (see Fingerings and Rhythm). The rhythmic figure should determine our fingerings in the sense that we want ideally to avoid shifting or string crossings just after the short note as this is when we have the least time. Some good examples of repertoire study material for this rhythmic figure, played fast and repeated over and over, come from the first movement of Beethoven’s 7th Symphony and the Gigue of Bach’s 5th Solo Cello Suite. We can treat both of these pieces as studies, playing the Bach with a metronome and playing the Beethoven with a recording (which not only has the function of a metronome but also makes the whole experience infinitely more enjoyable). In the Beethoven movement, this little rhythmic motif appears in almost 80% of its bars (measures), which is why we present that cello part here as a sort of study (click on the link). In the combination of the cello part with the other orchestral voices, every possible configuration of this rhythmic motif can be found.

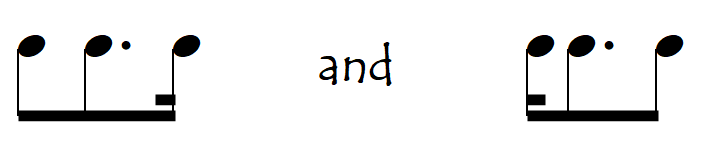

We can also work on scales, arpeggios etc with the less common compound dotted figures of:

Unlike duplet and triplet dotted rhythm figures, the compound-time versions can be bowed “as it comes” without the bow gradually disappearing past the tip. Each group of two consecutive figures has a neutral effect on the bow’s position, with the bow coming back automatically to where it started after the second figure of each pair. If, however, we do these figures with hooked bowings we are taking always two steps in one direction and one step in the other so here, again unlike the duplet hooked bowing, we are entering into unbalanced territory and need to be careful not to give unwanted accents (see “Bow Division” in the Bow Speed page).

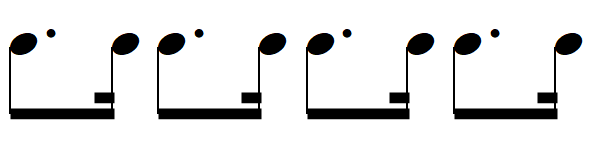

BINARY (DUPLET) DOTTED RHYTHMS

Here we are talking about our typical, standard, tight, “quadrupletised” dotted figure, the most commonly used dotted form in classical music:

These are the tightest form of dotted rhythms of the three that we have looked at on this page (although doubledotted figures are of course even tighter). Like triplet dotted figures, when these rhythms are repeated non-legato then they pose bowdivison problems because separate, as-it-comes bowings tend to take us quickly to the end of the bow or require large accents on the short notes in order to stay in the same part of the bow. This is why we most commonly use “hooked” bowings when we have a repeated series of these figures.

Fritz Kreisler’s “Liebesleid” is an excellent piece that we can use as a very enjoyable way to work on (and experiment with) dotted rhythms and hooked bowings.

In the following compilations of dotted rhythm repertoire passages, the material is presented in approximate order of difficulty.

Ternary (Tripletised) Dotted Rhythms: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

Compound-time Dotted Rhythms: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

Binary (Quad) Dotted Rhythms: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS