Tuning and Basic Warmup

Apart from their shared fundamental importance, the only thing that “tuning” and “warmup” have in common is that we do them both before we actually start “playing” (or practising). This is why we are including them together on this same page.

WARM-UP (AND CALM DOWN)

The “warmup” is one of those absolutely basic concepts that is so fundamental that it is almost unclassifiable. Warmup for our bodies is like oil for a machine or water for a dried-up cleaning sponge: an almost magical ingredient which converts a useless stiff, rigid and unresponsive object into a fluid, tactile and responsive instrument. Just like for dancers and athletes, the warmup is a physical (technical) necessity for flowing, high-performance, injury-free movements. But at the same time, our warmup – especially if it is a pre-performance warmup – also has an important psychological function in that a good warm-up not only warms up our body, but also calms down our mind.

We could therefore classify “The Warm-Up” simultaneously in both the “Basic Technical Principles” and the “Psychology” sections. Because of this overlapping of the two foundation categories, we have classified “Basic Warm-Up” in the “Miscellaneous” section, but the different sub-categories of the warmup are found in their respective sections (Left-hand, Right-hand, and Psychology).

Left Hand Warmup Right Hand Warmup Warmup = Calmdown

TUNING

Probably the most common way of tuning is playing the open strings in pairs and thus tuning using perfect fifth intervals. Unisons and fourths are however perhaps easier to hear – and therefore to tune – than fifths. According to the excellent cellist and teacher James Tennant, if we tune in fourths, we end up with a C-string nice and high, which is what it needs to be if we want it perfectly in tune with the piano. He suggests tuning in the following way:

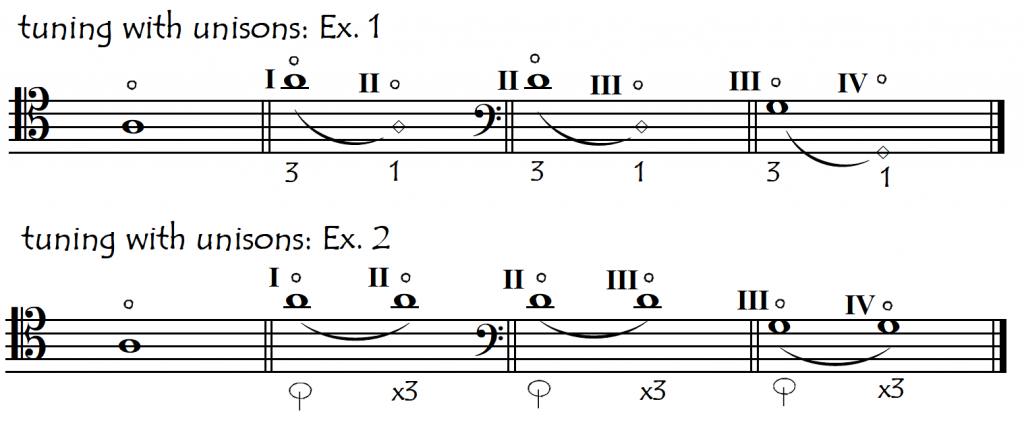

We can also tune with unisons. The traditional “unison tuning” method is shown in the first example below, but possibly the second example (Ex. 2 ) would be a better way of unison tuning. Both examples use exactly the same pitches (unisons) but the Ex. 2 fingering variant brings us two advantages: not only can we now play the two notes at the same time (if we want to), but also this tuning method requires having our hand in thumbposition, which is a nice way to get us up the fingerboard and out of our comfort zone before we even start really playing:

TUNING FROM THE BOTTOM UP

We almost always start tuning with our “A”-string and then work downwards, but this system only works well for the fine adjustments. Major tuning alterations to the lower strings greatly affect the tuning of higher strings (much more than the reverse situation) and can mean that all our previous fine-tuning of them is wasted, obliging us to start again from zero. So, after changing a lower string – or any other radical tuning situation affecting our lower strings – it is probably a good idea to start tuning from the bottom up, until our strings are roughly in tune.

WHEN IN DOUBT ……. SOLVING A TUNING CRISIS

The safest way to tune our instrument is with an electronic tuner or a phone app: these don’t lie and nor do they get confused or stressed out. This is the Science of tuning, rather than the Art of tuning. Tuning in this way just before a performance gives us a guaranteed good start, but it doesn’t last forever. Temperature changes between backstage and onstage and a multitude of other factors mean that our tuning moves and we may need to retune at opportune moments onstage. Sometimes we just can’t work out what is wrong with our fifth, fourth or unison. This – of course – tends to happen in the worst possible moment, when we are on stage, in front of an expectant audience. Whether onstage or peacefully at home, a good way to work out immediately whether the interval between two open strings needs to be widened or narrowed is by placing the first finger right next to the nut at the top of the fingerboard (on any one of the two strings) and seeing what the effect is of sharpening either of the strings. This is similar to the way violinists and violists tune, using their pegs to slide into the note from below. We can hear an interval better – and can therefore tune it better – when it is moving. For this same reason, we shift more accurately when we can hear our glissando.

ON-STAGE TUNING: AS DISCREETLY AS POSSIBLE

It is so uninspiring, when watching a concert, to have to hear people tuning up loudly on stage. Imagine the effect if an actor/presenter walked out on stage, then cleared their throat ten times and checked their hair, buttons and shoelaces before starting the performance. Well, that would be the equivalent to what we musicians do a lot of the time, and it is a real atmosphere-killer.

The performance begins from the moment the musicians walk out onto the stage. For orchestras, this onstage tuning is inevitable, but for smaller groups, the less noisy tuning we do onstage the better. We can tune up backstage, which is made especially easy nowadays with smartphone tuning apps. And we can do an awful lot of fine-tuning onstage just with soft lefthand plucking of the open strings.