Orchestral Playing

The defining – and unique – characteristic of “orchestral” playing is that here we play our musical line simultaneously with at least one other cellist. This has both advantages and disadvantages. On this page, we will look at a few ideas about how to make the most of the advantages of playing in unison with a group. On a separate page will be discussed some of the unique Difficulties of Orchestral Playing.

The main advantage of playing in unison with others is that it takes the pressure off. If we are insecure about a note, a rhythm, a shift, a passage etc then we can literally just release the pressure of the bow on the string and “fake it” until we are in secure territory again, hoping of course that the other players in the section will not be doing the same and that nobody will realise. This is not a recommendation for “faking” but rather just the recognition of an important unwritten rule of orchestral intelligence: that it is much less damaging to a section if we choose to “fake it” rather than to play the passage “honestly but badly”. Following this philosophy, a front-stand violinist took all the rosin off his bow for the first rehearsal of a difficult piece that he had not had time to prepare at all. Unfortunately the conductor, also a violinist, asked for this player’s instrument and bow to demonstrate a passage!!

DIVISI

The fact that we are many cellists playing at the same time doesn’t mean that we are always necessarily obliged to be playing the same notes at the same time. “Divisi” – dividing up the notes within the section – is a device that composers often use, but is also a device that we can sometimes appropriate and use of our own initiative even when it is not indicated by the composer. Let’s look first at how we can best distribute the different voices in those divisis that are indicated by the composer.

DISTRIBUTION OF DIVISI VOICES

We have two principal concerns in our decision about how to divide up the voices: balance (relative volume of each voice) and ease of playing together. Balance is normally just a question of numbers. Very often in a divisi there will be an important melodic line in the higher voice while the lower voice will be simply doubling the double basses. In these cases we can choose to put more cellists on the top line, even though the composer maybe doesn’t specify this. Here, for ease of playing together, the bottom line should be played preferably by the cellists at the back of the section, because they are the closest to the basses.

DIVISI IN TWO VOICES

In this most common type of divisi, each stand normally divides “outside-inside” (top voice-bottom voice). In some rhythmically tricky divisis however, it may help to divide the group front-back, in order for each voice to be grouped in a tighter block, which makes it is easier for each individual player to hear the other players of the same voice, and thus to play it together. A good example of this is found in the opening of the Allegro section in the First Movement of Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony.

DIVISI INTO THREE OR MORE PARTS

In a section of 8 cellists, a divisi into four different voices poses no intellectual problem of how to divide up the lines. But what about a divisi into 3 voices? The unthinking way is to maintain the same “divisi by stand” and get the fourth stand to divide between first and second voice, but this can cause difficulties of intonation and rhythmic security because the players of the fourth stand are quite disconnected from the front two stands with whom they need to play their two different voices in unison. The same type of problem occurs with divisi into 3 or 4 voices in a section of 10 or 12 cellists: the unthinking “divisi by stand” just doesn’t help for this same reason.

To avoid these difficulties of disconnection (distance) it helps to keep each voice in a more compact “block” of players, who can hear and see each other because they are all next to each other. We can achieve this by following a simple basic rule: lower voices at the back, higher voices at the front, and distribution of the voices in blocks according to the desired balance. This could give the following distributions:

Div a 4: 8 cellos Div a 3: 8 cellos Div a 3: 10 cellos Div a 4: 10 cellos

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

2 2 1 2 1 1 1 2

3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2

4 4 3 3 2 3 3 3

– – – – 3 3 4 4

USING DIVISI OF OUR OWN INITIATIVE: DIVEASY

Rather than faking, one of the best ways in which we can overcome “tricky passages” is by using our intelligence to divide up those tricky notes with our stand partner. In other words, by making certain moments/passages “divisi” (or, in these cases “diveasy”) we can ensure that all of the notes get played without anyone having to perform technical miracles. Most composers were not cellists, and we can sometimes do both them, ourselves, and the audience a big favour by using our cellistic knowledge to create our own divisis, thus ensuring that the composer’s original ideas will sound as good as possible.

Unfortunately, it seems that most of us orchestral musicians prefer to suffer rather than use our brains to work out how to share the load. There are several reasons for this: respect for the composer’s original notation, fear of doing something different, intellectual laziness, the difficulty (or impossibility) of notating or memorising the divisi in the existing part and, ultimately, our delegation of all intellectual responsibility to conductors. The ideal orchestral player is a top-class machine, playing everything that is written on the page without asking any questions or creating any problems (see Difficulties of Orchestral Playing).

Rather than showing a lack of respect for composers or conductors, our potential divisi redistributions of the notes are simply helping to achieve the composer’s original intentions, by avoiding the risk of the passage(s) sounding awful (or of having the whole section faking it). In this way we have improved the composition (without changing any notes) and made it easier for ourselves …. so who could possibly be against it ?? Let’s look now at some of these situations:

1. MAKING DOUBLE-STOPS DIVISI

The most obvious example of using divisi on our own initiative to make the music sound better as well as making our life easier is in the avoidance of double-stops. Double-stops make one good player sound like two bad ones, and there are good reasons to convert all double-stops in orchestral music into divisi, even when the composer specifically says “non-divisi”. Composers just don’t realise that the volume of sound when played divisi can be exactly the same as when played non-divisi, while the intonation is incomparably more secure.

2. REDISTRIBUTING THE NOTES IN DIFFICULT PASSAGES

Sometimes it may be advantageous to “rearrange” a passage, dividing the notes between the inside and outside players in each stand. The following example from the first movement of Schumann’s 2nd Symphony illustrates this situation perfectly:

Schumann was a pianist and composed at the piano. While his original cello part (top line) sounds wonderful on the piano, it can sound very bad on the cello as it is so hard for any one cellist to play those octaves both legato and in tune. This passage sounds much better, and is much easier to play if we rearrange it to make it “divisi” as shown in the second line.

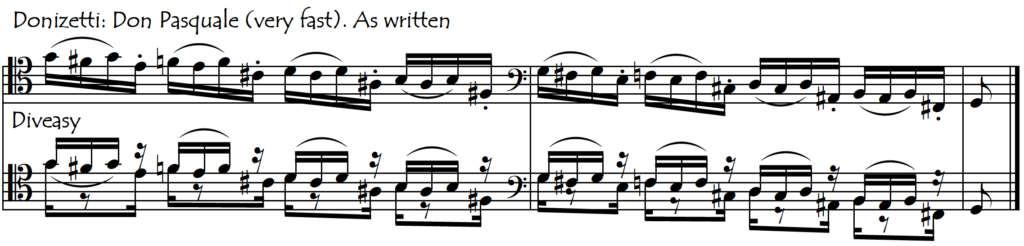

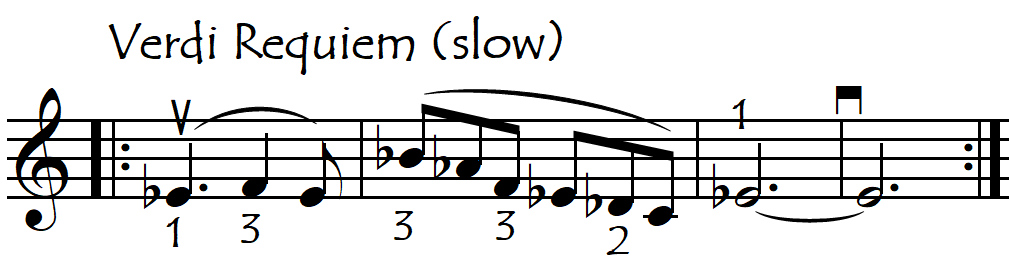

In the above example, divisi helped us play the passage in tune. At other times a divisi note redistribution can make an impossible fast passage suddenly easy:

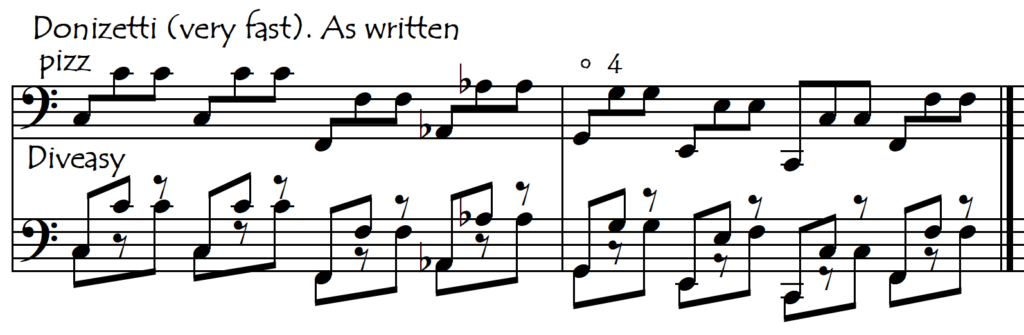

Many fast pizzicato passages are only possible in the composer’s head (or at the keyboard). They notate their fast pizzicato passages simply as they sound and leave it to the players to work out how to play them. If we want to avoid tension, stress, and insecurity, we will need to use our intelligence to work out how best to divide up the notes between the players. With a simple note redistribution (sharing of the load), even the fastest, most awkward pizzicato passages can be made easy as in the following excerpt from the same opera:

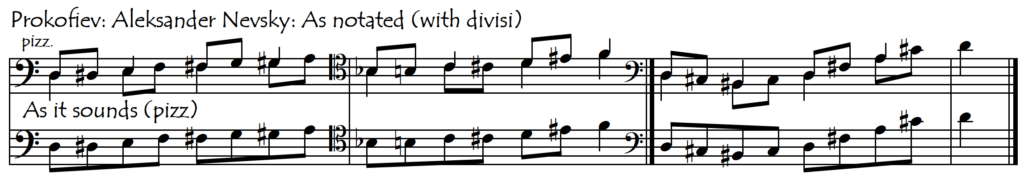

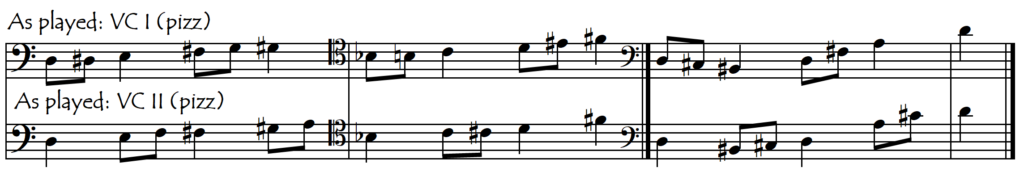

Prokofiev is one of the few composers who understood this possibility and he often notates his fast pizzicato passages with the divisi incorporated into the notation. This looks complicated, but once we have studied the passage carefully the end result of the divisi is much more secure and much easier to play than if each cellist tries to play all of the notes:

Prokofiev’s divisi notation is one large step towards making our job easier. Another step in player-friendliness would be to actually notate the divisi on two staves, thus making it much easier to read. Unfortunately, this is a luxury that we rarely see:

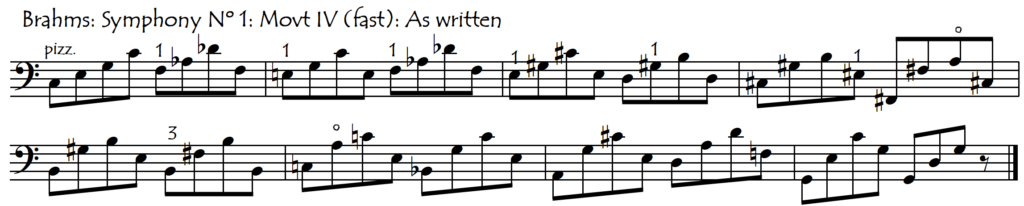

Here is another example of a fast pizzicato passage that can be played “diveasy” :

This passage could be played with the following divisi. Unfortunately, it is difficult (and possibly ugly and confusing) to try and notate this in the existing part, so we will just have to remember who plays what:

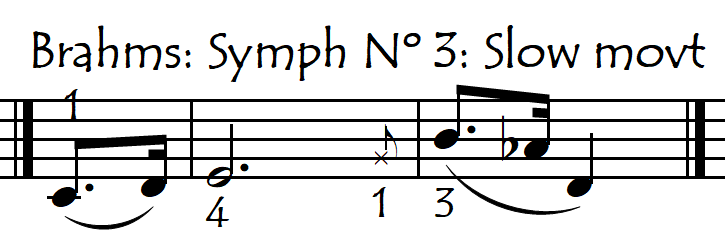

3. DIVISI FOR RAPID ARCO-PIZZICATO TRANSITIONS

This same concept can be very useful in rapid changes between “arco” and “pizzicato”. Very often, composers don’t realise how much time we need to change between the two, and when this occurs we have an unstable moment of panic as we rush to change our bowhand posture in time. In these cases, by making the transition between “arco” and “pizz” divisi (one player “finishes” comfortably, the other player “starts” comfortably), we can immediately ensure that all the notes are played with rhythmical security, musicality, and with absolute ease of execution. This requires a simple agreement with our stand partner to decide who the “finisher” is and who the “starter” is but will function even better as a permanent understanding for the whole section, for example, inside = starters and outside = finishers (or vice versa).

*************************************************************************************************

OTHER TIPS FOR ORCHESTRAL PLAYING

ORCHESTRAL SHIFTING: ARTICULATED SAFER THAN GLISSANDO

Glissando shifts are more expressive, lyrical, vocal, and beautiful than articulated shifts, but their intonation security depends on our perfect audio control of the glissando. This perfect control requires that we can hear ourselves clearly in order to know exactly when we have arrived at the destination note. Unfortunately, in an orchestra, we very often can’t hear ourselves well enough to be able to really control our glissando shift arrivals. There is just too much noise going on. Even if it is only the cello section that is playing, all that other aural feedback from people playing exactly the same notes all around us can mean that we can’t distinguish our own sound well enough to be able to really hear and control our glissando shift. And if we add trombones, percussion etc then we can easily lose our exact perception of our own sound and intonation.

When we articulate the target finger in a shift we are using a different method of spatial control: more absolute (knowing the target position) than relative (measuring the distance from the previous note). This is why when we can’t measure our shift distances aurally because of the general noise level around us, then articulated shifts are often a safer option.

Of course, some shifts cannot be articulated, most notably same-finger shifts, so this trick is mostly applicable to assisted shifts upwards and to scale/arpeggio-type shifts downwards, both of which feature in the above example. We can however also use this little trick unexpectedly for scale/arpeggio-type shifts upwards on the higher fingers, in which we can insert a first finger intermediate note to make also the upwards shift articulated (and therefore more secure).

LONG RESTS = HOLIDAY?

In a symphony orchestra there are so many instruments available for the composer, that quite often we have multi-bar rests while other instruments continue playing.

When playing alone or in a small group not only do we have less of these extended rest periods but also we tend to feel more involved, which keeps our attention on the music even during our rests. But in a large group, it is very easy to “switch off” when we see a long rest. Unfortunately, a stage performance is not like a filmed performance. In a filmed concert, the camera can zoom in on any one player or group in their special moment and in that case it doesn’t matter what the other musicians are doing during their “rests”. On stage, however, we are all part of the performance, and if some resting musicians are having a mini-holiday during their rests then they can easily (and inadvertently) disturb and distract from the performance of those who are playing. It’s a little like football – even if we don’t have the ball at our feet, we always need to have our eye (attention) on it. In football, the players need to do this because the ball might suddenly come to them at any time. In music, we do this simply out of respect for our colleagues and the public, even when we know that the ball won’t come back to us for 10 bars …..