Fingertips or Pads? Elbow Height?

DUCK FOOT OR EAGLE CLAW?

As a general rule, we cellists – unlike violinists and ballet dancers – need to stop the strings more with the pads of the fingers rather than the fingertips. The softness and size of the finger pad (in contrast to the fingertip) is ideal for making a warm, juicy, rounded sound and a luscious vibrato. Unless we have very big, wide, chunky, “sausage” fingers, the surface area in contact with the string when using the fingertips is likely to be too small to make this same warm sound. This is especially true for the little finger, whose fingertip is the smallest of all the fingers. And it is especially true also for cellists with narrow (thin) fingers.

Lucky are those string players who have “spatula” type fingertips (with wide juicy pads). This helps enormously to make a good sound and a good vibrato. It would appear that this vaguely blurred, fuzzy limit to the pitch of the note, given by the soft edges and succulent body of the finger pad, gives to our vibrato (and even maybe to our basic sound) a certain human quality that would be entirely lost if we were to hold the string down (stop) with a straight-edged hard object.

As an experiment, it is both amusing and illuminating to play the cello sometimes with our point of finger-string contact displaced to a zone (area, point) situated as far back on the fingerpad (in other words, as far away from the fingertip) as possible. The fingers will need to be quite flat, like a duck’s foot, rather than tightly curled like the claw of a bird of prey. The consequences of this hand-posture on the way we articulate the fingers, on our vibrato and on the sound we make might be quite revolutionary. We might even start to feel, look and sound a little like Yo Yo Ma !

ON THE INFLUENCE OF LEFT-ELBOW HEIGHT

As a child I remember the constant advice to “keep your elbow high”. This was very mistaken advice, especially when playing on the “A”-string!

The height at which we hold our left elbow while playing has a major influence on the type of finger contact (tips or pads) that we have with the string. Keeping the elbow low facilitates playing with the pads as it places the fingers more horizontally, whereas raising the elbow higher has exactly the opposite effect. The need for the low elbow (as a means to get the fingers onto their pads) increases as we go from the lower to the higher strings because of the curve of the cello fingerboard. In addition to this, in order to get a warm, rounded sound on the “A”-string – the thinnest and most strident of all our strings – our need for the soft juicy fingerpads (rather than the harder fingertips) is at a maximum. Therefore it is on the “A”-string that our need for a low elbow is the greatest.

For playing in extended position, the low elbow not only allows us to play on the fingerpads but also helps the fingers to open out (extend) because it allows the wrist to flex (the top-side of the wrist joint angling up into the air and the fingertips now being well below the height of the wrist joint). A high elbow, on the other hand, causes the wrist joint to collapse, bending in the opposite direction. Now our fingertips are higher than the level of the wrist joint and our hand posture is converted into more of a “claw“. This “claw” hand-posture has the doubly negative effect of both placing the fingers more on their tips, and hindering their ability to extend away from each other. Therefore, our absolutely greatest need for a low elbow occurs when we are playing in extended position on the “A”-string.

SEATING POSTURE, LONG LEGS AND FLAT PADS

Surprisingly, cellists with long legs have an advantage when it comes to playing with the fingerpads on the “A”-string because those long legs allow them to roll the cello around on its spike axis, rotating the”A”-string-side of the fingerboard higher, into a much more ergonomic position for both the left-hand and the bow. Short-legged cellists are limited in their ability to do this rotation because, after a certain (very early) point in the rotation, the left leg can no longer grip/block the side of the cello and we are no longer in a viable playing posture. One way for short-legged cellists to see how much nicer it is to play with the cello rotated around is to put a little stool (like a guitarist’s foot-stool) under the left foot. Now the knee and thigh are raised up and we are consequently able to rotate the cello a whole lot more without losing our vital leg/cello point of contact.

Alternatively, for short-legged cellists, to facilitate playing on the fingerpads without needing a stool or a leg-lengthening operation, we can shorten the spike, bringing its point of contact with the floor closer in towards our body. This has the effect of making the cello more vertical, which allows us to rotate it a little further around before our left leg loses its contact with the instrument. Basically, the more vertical the cello is (the closer the spike point is to our body), the more we will be able to rotate it in this favourable direction, and consequently the easier it will be to play on the pads on the A-string. (See Seating Posture).

WHEN MIGHT WE WANT TO PLAY ON THE TIPS??

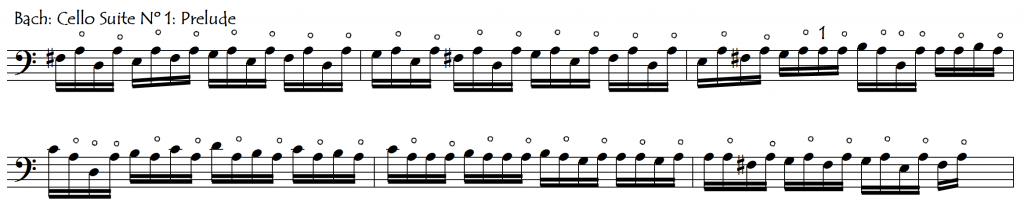

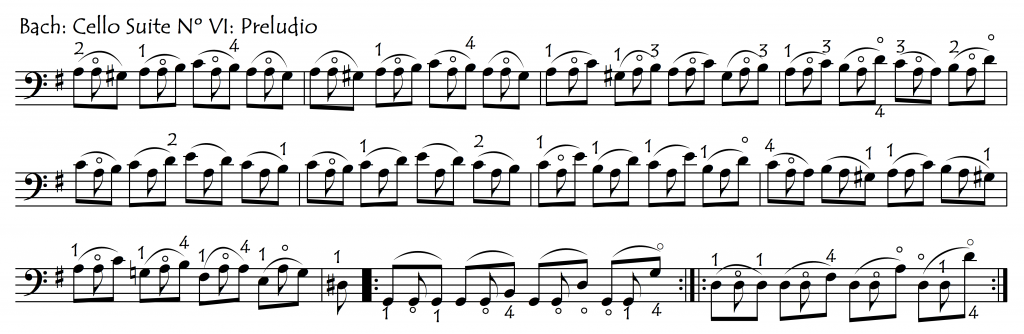

- IN FAST ARTICULATED PASSAGES

Of course, for fast articulated passages, this warm and rounded sound becomes less important. In these types of passages we need clarity above all, and can use a more drum-like articulation, for which the fingertips – harder and less mushy than the pads – may be more suitable.

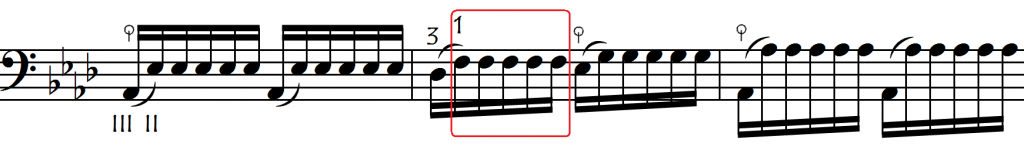

- WHEN WE NEED THE HIGHER OPEN STRING TO SOUND

Another situation in which we need to play on our fingertips is when we are also sounding the string above that on which our lefthand is playing. In other words, when we are playing doublestops (or broken doublestops) or simply doing a string crossing to a higher string with either an open string or a lower finger on the higher string. In these situations, unless we play on our fingertips, the fingers playing on the lower string will touch (and thus disturb the sounding of) the higher string. This is most pronounced when the higher string is an open string, because the open string is significantly higher off the fingerboard than the stopped string, thus is more easily disturbed by the fingers stopping the lower string.

If the crossings are slurred it becomes even easier to hear if the higher open string is being disturbed by the lower-string fingers or if it is, on the contrary, ringing freely and constantly throughout the passage as we want it to do.

If we can get that open string ringing uninterruptedly, without its vibration being interfered with by the fingers on the lower string, then these passages sound really magnificent. This is certainly how they are meant to sound.

The following links open up several pages of downloadable (printable) study material for “playing on the tips”. All of this material makes use of the doublestopped (or broken) higher open string to oblige us to keep our fingers on their tips:

NEITHER TIPS NOR PADS: BIZARRE WAYS OF STOPPING THE STRING

In some situations – normally where we don’t need vibrato or an especially good sound – we can stop the strings in some very unorthodox ways. For example, the use of the first finger in thumbposition in the neck region, where the string is stopped from the side rather than above, and the finger is in a completely curled position. The discomfort – and frequency – of this posture is one of the reasons why we don’t use thumbposition in the neck region much!