Rushing For Musicians: The Panic Response

Why do we rush when we have a difficult passage ? Why is it that, just at that precise moment in which we need all the time and relaxation that we can possibly find (in order to do our difficult passage with as little stress as possible), we rush like crazy, thus making a difficult passage even more difficult ?

Human nature seems to suffer the defect that when we are in a hurry, we can very easily fall into the trap of doing things too fast. This is the “panic response”. “Too fast” is, by definition, any speed above which we start to lose control, and this is when accidents start to happen. The musical manifestation of this “natural psychological law” is that we tend to rush the most, difficult, complex passages (these are the ones we call “fast”).

When we think “this passage is fast”, then we also tend to think not only that it has to feel “difficult” but also even that it has to go “as fast as possible”. Here we are measuring the speed subjectively, confusing speed with difficulty (see Fast Playing). In this state of panic, overwhelmed by an overdose of demands on our brain and body and therefore in a state of high tension, we lose our logical reasoning capacities and can no longer feel the steady pulse or hear the other musicians (or the metronome).

MENTAL ACCELERATION

Another unfortunate fact (defect) of human nature is that the faster we do things, the more impatient and accelerated we tend to become. This is Newton’s First Law of Motion (also called the Law of Inertia) in its psychological manifestation. Whereas mechanical objects tend to slow down under the effect of friction, the mind has no friction, so once it starts accelerating it becomes – unless we consciously put the brakes on – like a rocket hurtling through space with nothing to slow it down. This is why, on top of a general human tendency to panic in the fastest, most difficult situations (or musical passages), some people – accelerated, nervous, fast-speaking and fast-thinking types – have a greater tendency to rush than others. See Calm in the Psychology section.

BRAIN OVERLOAD

Rushing is just one symptom of the loss of control that occurs when our brain is overloaded. We are literally so tied up in our own problems, so self-absorbed, that we have no brain space free to pay attention to what is going on around us. Whereas a computer that doesn’t have enough RAM memory or processing power might go slower before ultimately grinding to a halt, a musician in the same circumstances will often accelerate until ultimately crashing, out of control, at top speed.

Normally, this overload is caused by the fact that the passage we are playing is stretching our technical capacities to the limit (or beyond). Stagefright also saturates our brain and causes it to overload. Sadly and ironically, the speed at which the panic response sets is inversely proportional to our tension level. In other words, the more tense we are, the lower the speed necessary to make us freak out (lose control and rush or get in a tangle). If we are feeling comfortable with the passage, the piece, the cello, ourselves and the situation, then we are more likely to be calm …….. and therefore less likely to rush.

SOLUTIONS

Here are some specific practice techniques for eliminating the “rushing response”:

START SLOW AND BAN THE METRONOME (AT FIRST)

When learning a new language, we have to slow it down to a speed at which we can both:

- understand what is said to us with ease, and

- pronounce each sound of what we want to say correctly.

If it all goes too quickly, our brain can’t keep up, and when this happens, not only do we learn nothing but also we get into the very unsatisfying habit of chaos, muddle, confusion, tangled threads and tension. Learning our instrument, or a new musical passage, is exactly the same: if we don’t slow it down enough that we can play it well (= relaxed, in tune, in time, and with a good sound) then we will probably never get better, and in fact, risk getting into the habit of doing “it” badly (tensely, out of tune, too fast and with an ugly sound) forever – or at least until we finally slow it down! Once we actually slow a passage down to this “easy” level, it is extraordinary how quickly it can be mastered but if we never allow ourselves the luxury of playing it slow enough, we can spend hours not only making it worse but also reinforcing a general habit of playing tensely and rushing!

To achieve this vital state of relaxation and control it helps enormously to ignore the concept of a stable tempo, banning all ideas of metronomic discipline and allowing ourselves to slow down our playing whenever we get to anything difficult. Metronomes (or pre-recorded accompaniments) are extremely useful as an ultimate test of our mastery of a passage but the rhythmical discipline that they impose in difficult passages can be such a difficult, demanding taskmaster that their end result can actually be counter-productive due to the excessive tension created.

How ironic and counterintuitive it is that a metronome can actually cause rushing, but this is only when it imposes a speed that is too fast for us for certain passages or movements. Using a metronome to slow us down is, on the contrary, an excellent tool to help us overcome our rushing.

THINK “SLOW”, USE A METRONOME AND PLAY BEHIND THE METRONOME BEAT.

When we play a fast passage “a tempo” (at speed), it is helpful to think the absolute opposite of “fast”. We need to think “slow” or even, “as slow and easy as possible”. Here is where the metronome is a godsend, teacher, saviour and guardian angel, giving us the mental brakes that can save us from crashing. A metronome can be lethal for slower, expressive music, but for working on fast passages no tool is more useful. Non-judgemental, impartial, perfectly objective, just like a SatNav (G.P.S.) it will never shout at you when you ignore it. You however may be tempted to shout at it when it “decides to slow down” in the middle of your fast passage. It is truly amazing how slowly it actually goes in the fastest, trickiest passages!

It’s a good idea to practice our fast playing not just “in time” with the metronome, but even sometimes a tiny bit behind it, in order to get used not only to not rushing, but also to playing as slowly as possible without actually being left behind by the metronome. It’s surprising just how much extra time we have when we do this. It really does make a big difference to be just a tiny bit behind the metronome rather than a tiny bit ahead of it. In this way we are testing the lower limit to the fastest passages, rather than always testing the upper limit (the speed at which we crash). We can do this best when the metronome is beating slowly, for example the metronome can be beating minims (half notes) while we are playing semiquavers.

Fast in music should be a physical phenomenon, but not a psychological one. In fact we could probably say that as a general rule, the faster we move, the slower we need to think, in order to avoid losing control.

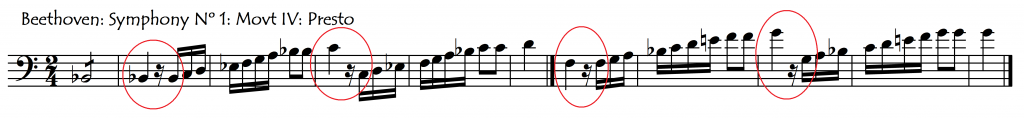

FEEL (COUNT) THE FAST PULSE VALUES: DOTTED RHYTHMS, SYNCOPATIONS AND MISSING BEATS

Some passages lend themselves more to rushing than others. Certainly, when a beat is tied over (and thus we don’t play a new note or impulse on the beat), it becomes much easier to rush. Because we are not “making” the beat, we tend not to wait long enough for it and thus can easily overanticipate the following note(s). This phenomenon is especially pronounced when we have a long note (or rest) followed by short rapid notes: we tend to take off on the short notes too early. We call this “eating” the long note – it’s as though we have eaten the end off it! :

The solution is to keep, during the long notes or rests, our internal metronome beating the small, fast values that we are going to have to play immediately afterwards. It is so easy to get lazy and go to sleep during long notes (or rests). If we do that, then our wake-up tends to be in a panic! In the above excerpt, for example, we need to keep feeling semiquavers during the long notes and the rests. Practicing with the metronome beating the small subdivisions is a good way to get us used to feeling those smallest, fastest, rhythmic values.

The music of Vivaldi gives us a lot of delightful material of this type for working on our rushing tendencies. The following study, based on excerpts from his music, should be played with the metronome. It is all in simple thumbposition so that we can work on two skills at once: our rhythmic control and our comfort in thumbposition.

3: OTHER PRACTICE METHODS

On the page dedicated to “Fast and Tricky“, there is a whole section on practice methods for fast passages.