Choosing Bowings

Bowings are like a painter’s brushstrokes and, together with our choice of fingerings, make a huge difference, not only to how the music will sound but also to how easy or difficult it is to play. In paradise, all gentle bow-starts are at the tip, all sforzandos at the frog, all diminuendos fall on down-bows and all crescendos on up-bows. Unfortunately, in real life it’s not so easy, and finding “the best” bowings for any passage can be a complex engineering puzzle, a mathematical juggling act requiring the balancing and reconciling of many different technical, acoustical and musical (interpretative) factors. Choosing bowings is at the same time an inspired art (like choreography for a dancer) and a pure science (arcology?). It is an “art” in the sense that our primary consideration is the musical idea: of how we want the passage to sound. It is only when we have this idea that we can then start to apply our scientific (or intuitive) mathematical intelligence in order to try to find those special bowings that will most easily help us achieve this artistic goal. Our choices of both bowings and fingerings contribute greatly to our interpretation and constitute one of the major differences between clumsy sight-reading and masterly performance. Choosing bowings (and fingerings) is creative, instructive, mind-opening ……. and fun.

We have included this article in the “Technique” department because our goal here is to understand the science of bowings in order to be able to achieve our interpretative objectives. Normally our musical intentions are much stronger and healthier than our awareness of the ways in which we can use our choice of bowings to achieve these goals. In other words, most commonly it is our understanding of bowing science that is the weakest link in the interpretative chain, and it is our “sub-optimal” (bad) bowings that are getting in the way of our great musical intentions. It is of course possible to play very well in spite of using sub-optimal bowings, but finding a “good” bowing can make our job so much easier.

“UP” AND “DOWN” BOWS: THE CONFUSION OF LANGUAGE!!

The terms “up bow” and “down bow” represent quite a strange use of language, as the directions in which the bow actually travels on the cello have no relation to the traditional concepts of “up” and “down”. Had Isaac Newton played the cello he might have become quite confused about the meaning of these words ….. and might even never have discovered gravity! If we however play the cello while lying down, on the edge of a bed or sofa, with the instrument rotated 90º clockwise, we will then understand perfectly why the terms “up” and “down” are used to describe the bow stroke directions!

These terms, of course, come directly from violin playing, and would indicate in fact that the violin used to be held in a position more rotated clockwise than nowadays (in the gipsy/country-fiddler posture). In this position, the violinist’s arm really does “push up” for the up-bow and “pull” (or fall) down for the down-bow. For the cello, the words “to the left” and “to the right” would be more appropriate descriptions of the bow directions than “up” and “down”.

The french however have a different way of describing the two bow directions: they use the terminology of “push-pull” rather than “up-down”: the upbow is called “pushed” (poussé) while the downbow is called “pulled” (tiré). This is also a strange use of language because a push-pull movement usually refers to a movement that is made in an axis towards and away from the body, as if the bow were a saw (or a sword) pointing straight out in front of us. Despite the directional confusion, “push” and “pull” are a more helpful way of describing the bow-stroke directions than our english “up” and “down”, because push and pull both imply that we are working against a certain resistance, rather than just going in a certain direction. And what’s more, these terms are as valid for violin (and viola) as for cello and bass.

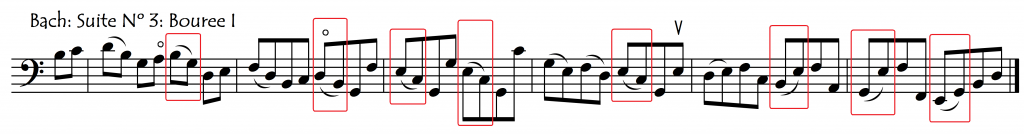

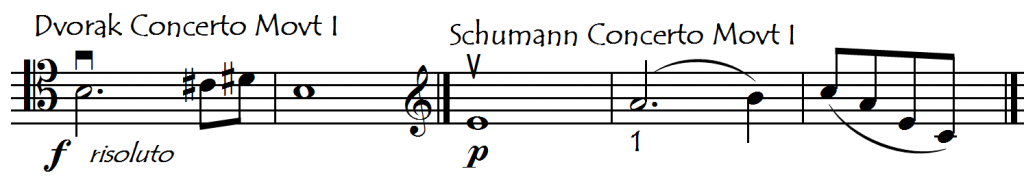

The origin of the bowing symbols is both curious and revealing. The downbow sign quite probably evolved from the letter “n” while the upbow sign evolved from the letter “v”. These letters were the abbreviated forms of the latin words “nobilis” (meaning strong, noble) and “vilis” (meaning exactly the contrary). French Renaissance and Baroque composers would place these “n” or “v” symbols above certain notes to indicate whether they were to be played strongly or weakly. To illustrate this opposing yin-yang natures of up and down bows, the opening cello themes of the two most famous cello concertos do a very good job: the Dvorak starts with a classic strong, accentuated downbow, while the Schumann starts with a beautiful gentle imperceptible smooth start, which would suit perfectly an upbow (although we will often play it downbow, for phrasing reasons).

“GOOD” AND “BAD” BOWINGS: MUCH LESS PERSONAL THAN FINGERINGS

Whereas our hand size often plays a large part in our choice of fingerings, it has no influence on our bowing choices. Because cello bows are all remarkably similar in length and weight, our choices of bowings are influenced primarily by mechanical, acoustical and interpretative factors (room resonance, type of ensemble and repertoire, need for volume or for intimacy) that are identical for all cellists independent of our personal unique physical characteristics. When we are choosing our bowings, the only variables that are truly “personal” are our musical taste, technical ability, and the particular characteristics of the cello and bow that we are using. Normally, therefore, a “good” bowing for a particular passage in a particular acoustic, will be good for anybody playing in those same acoustical conditions.

In the same way that a “good” fingering for a large hand might be totally unsuitable for a small hand, a particular bowing that suits a large hall might be quite inappropriate for a small intimate room (and vice-versa). But whereas a “bad” fingering might only be bad for the small cellist, the quality or deficiency in a choice of bowings will affect all cellists equally. Imagine if some cellists played with a bow twice (or half) the length and weight of a normal bow. In this case, the need for “personalised” bowings would be justified and this situation would correspond almost exactly with that of the differences in the sizes of different cellists’ left-hands. The intimate relation between acoustics and bowing choices corresponds to the equally intimate relation between hand size and fingering choices and the enormous variations in hand size between different cellists are probably about as significant for our choice of fingerings as are the enormous variations in the acoustic qualities between different rooms (and instruments) for choosing bowings.

Some people can play very well in spite of using illogical, unimaginative or uncomfortable bowings: now that is a sign of true talent and/or very good training and/or an excellent instrument/bow. Unfortunately however, having all these advantages can make those lucky cellists think “why bother” when it comes to thinking about whether a bowing can be improved or not. If such a cellist wins a job as section leader in an orchestra (and they often do), their group is going to need infinite patience. Ultimately, we need to learn both skills: how to choose the best bowings ……. but also how to play the worst bowings!

WORKING BACKWARDS

In any piece of music, there are some passages (figures, bars or notes) for which the choice of bow direction is both absolutely clear and very important. When we begin to bow a new piece, we need to start by putting in the bowings for these passages. Then we can just fill in the other bits (in which the bowings are less important) in the best way possible but always in such a way as to arrive at those critical passages in the right direction and in the right part of the bow. This means that, in order to avoid “backwards” (unfavourable) bowings, it helps to also work backwards !

AUTOMATIC ALTERNATION BETWEEN UP AND DOWNBOWS?

Please no !!!! This type of bowing is the curse of any orchestral string player who has the bad luck to have an unimaginative section leader.

Usually, the start of a new musical impulse coincides with a change of bow direction ………. but not always. It is very easy to think that, automatically after a down bow, the next bow stroke must be an up bow (and vice versa). But this is actually “thinking without thinking” (the worst type): an automated response that often doesn’t give the best possible solution to a musical or technical problem, or to any problem in fact. For many different reasons and in many different circumstances it might actually be a better idea to follow our initial bowstroke (up or downbow) with another (or others) in the same direction rather than a simple mechanical succession of opposing movements.

Especially at slower and moderate speeds, two (or more) successive impulses within one bow stroke can replicate almost exactly most of the variety of separate bow strokes. Even while continuing (restarting) in the same direction, the different notes can still be articulated with every possible degree of separation/connection from the extreme separation of crisp hooked dotted rhythms to the almost imperceptible reduction in volume between the notes of a throbbing portato (see below).

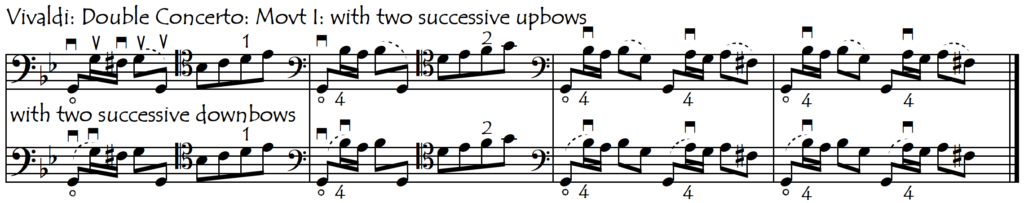

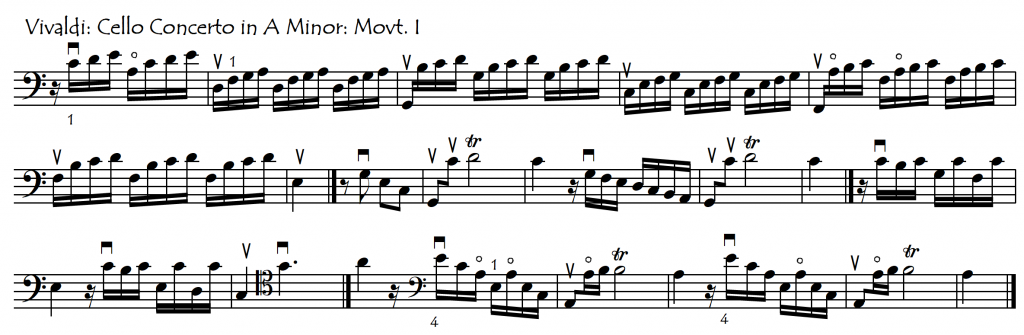

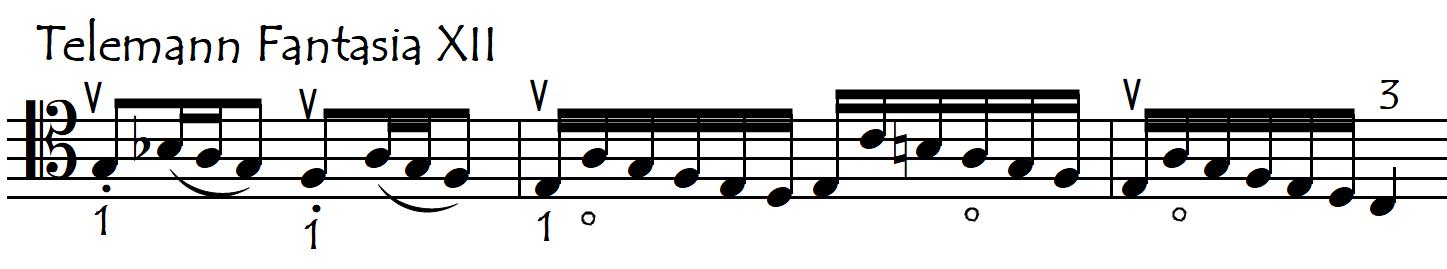

While we often play two successive upbows (in order to have our upbeat on an upbow), the use of successive downbows is something that comes less spontaneously/naturally and therefore requires more imagination. In the following example, the choice of two successive downbows takes us further away from the frog, encouraging us to use faster and lighter “italianate” bowstrokes. The two successive upbows, in contrast, bring us towards the frog where we are more likely to sound like a neolithic axe-murderer !

The separations between the consecutive bowstrokes in this Vivaldi example are mid-range separations (neither extremely separated nor extremely connected) in which simply our continuation in the same bow direction sounds exactly as if it were a new bowstroke in the opposite direction. The dotted slur indication, which is not used in standard notation, IS used (and very frequently) in all cellofun musical editions and illustrations. It indicates a new bowstroke, in the same direction as the previous one, which starts at the same place in the bow that the last bowstroke finished. Another way to refer to this type of bowing could be as “a broken slur”.

Consecutive bowstrokes in the same direction can be divided into several different types. Often, as in the above example, our use of this little “trick” is totally optional but at other times we absolutely need these bowings. Let’s look now at some of these special, most characteristic, cases, each of which has its own dedicated article (click on the links):

- THE “RETAKE”:

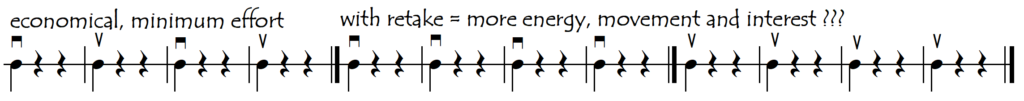

Here, between two notes played in the same bow direction, there is a “musical space” in which we bring the bow silently back in the opposite direction to the previous bowstroke before starting our new bowstroke in the same original direction. Words make this gesture sound complicated but it isn’t, as the following example will show. The retake movements are indicated in the example below by the arrows. Here, obviously, there is no dotted slur marking because a retake is not a broken slur but a completely new beginning, in another part of the bow:

Very often, the use of retakes will add attractive dance elements to our playing. As-it-comes bowings (in which we simply alternate up and down bows as though we were using a saw to cut wood) are usually the most simple and economical bowings in terms of energy expenditure and intellectual effort but are also the most neutral/inexpressive in terms of body language. Even though the use of retakes may not be necessary from a technical point of view (bow division, bow bounce etc), their use can add a huge amount of interest, character, energy and attractiveness to the same notes because now our bow and right arm are obliged to move a lot more. This concept is valid for music of any speed and dynamic:

The following link opens up a page dedicated to the subject of the retake:

- THE “HOOK”

Here, between two notes played in the same bow direction, there is a “musical space” (a silence filled only with resonance). Hooked bowings should sound like separate bows, but rather than changing the bowstroke direction we just take the pressure off completely and then start again, in the same direction but, in contrast to the retake, now in the same part of the bow where the previous stroke finished. The most common use of hooked bowings is in “unbalanced” figures such as dotted rhythms, in all their different manifestations. In the cellofun editions, hooked bowings are indicated by dotted/dashed slurs.

The following link opens up a page dedicated to the subject of hooked bowings:

- “PORTATO”

Here, between notes played in the same bow direction, there is much less “musical space”. In fact, normally, the idea/effect of the “portato” bowstroke is to produce a more legato connection than even the most legato separate bowstrokes, but less legato than a slur. Portato bowings are on a continuum with hooked bowings but are simply at the much more connected end of the spectrum. The reduction in pressure and bowspeed between the notes is therefore much less than in hooked bowings. This continuity allows us to connect more than two notes in a portato bow stroke, unlike for hooked bowings which almost always concern two notes in the same bow direction (pairs of notes), most often a long one followed by a short one. Portato bowings are normally indicated by slurs with lines, dotted lines, or dots on the notes. In the cellofun editions they can also be indicated by longer dotted slurs over other shorter solid slurs.

It is because of the similarities between portato and hooked bowings that they are looked at in detail on the same page as hooked bowings.

“Portato (and Hooked) Bowings“

DOWNBOW ON DOWNBEAT (AND UPBOW ON UPBEAT) ?

Even linguistically it seems that the upbow is made for the upbeat and the downbow for the downbeat. Although there are often very good ergonomic reasons why this little combo is a standard formula, sometimes however, it is not the best bowing option and, in these cases, it will be to our advantage to think “outside of the box” and do the reverse.

In this example, the main reason for our “reverse bowings” is to facilitate the string crossings (most notably the leaps across strings) and this subject is looked at in more detail later in this article. But multiple other reasons can also make reverse bowings advantageous and we have an entire article dedicated to this subject (see Reverse Bowings).

FACTORS INVOLVED IN OUR BOWING CHOICES

Let’s look now at some of the elements that influence our choice of bow directions:

1. THE COMPOSER’S ARTICULATION AND DYNAMIC INDICATIONS:

The articulations (including slurs) and dynamics that the composer has written are, of course, the most important starting point in our choice of bowings. Most composers are not experienced string players, let alone cellists, and sometimes, even bowings that are suitable for the violin (as written by Bach and Mozart for example) may not be suitable for the cello. The cello needs more bow and more separate articulations (to help the notes speak) than the violin. So we should feel justified in often using our cellistic intelligence to judge whether the composer’s bowing indications are absolutely the best instructions, or whether they can be improved.

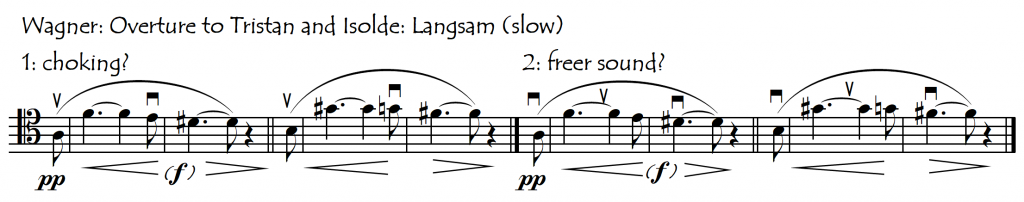

1:1 SLURS: BOW SPEED, DYNAMICS, AND SUFFOCATION

We have to be careful with how literally we interpret composers’ slur markings (or their absence). A slur is, more often than not, just a phrasing, indicating “legato” – especially if the composer was not a string player. Mozart was a string player and most of his slurs are exactly that: bowings. But Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Beethoven and many other composers, especially of the Romantic era, were pianists rather than string players and the “slurs” over their long, singing phrases are almost always phrasings rather than bowing indications. If we treat these “slurs” as bowing indications then we (and our listeners) are going to suffer (see below). At the other extreme, some composers may not even feel the need to use slurs to specify legato, especially if they are writing for singers. If we treat this lack of slurs literally and play the music with only separate bows then, once again, everyone will suffer.

One of the most common situations in which we will need to disregard the composer’s bowing/phrasing instructions occurs when we need to change our bow on a long slur (or on a long note) in order to be able to sustain it with a good sound. If we don’t change our bow, because we are considering the phrasing indications as bowings, then we will almost certainly end up using bow-strokes that are excessively long. This will give us a strangled or, at best, unexpansive sound in which bow pressure is overused as a sound-production mechanism in relation to bow speed. It is very hard to play expressively and make a beautiful sound under these conditions.

Using too little bow speed obliges us to either reduce the volume or use more bow pressure. Ultimately, we “run out of bow” in the same way that a singer can run out of breath if they don’t take enough opportunities to breathe. And just like singers, when our choice of bowings does not allow us enough bowspeed to make a free, warm sound then we feel that (and sound like) we are suffocating. A bow change is not the equivalent of a singer’s new breath and can be imperceptible, especially at the tip of the bow. This is not to say that practising with long slow bows is not a very useful yoga-like exercise to develop control: it is. But suffocating a musical phrase in order to fit it into one long bow-stroke is usually due to a misinterpretation of the composer’s phrasing indication and is seldom worth the effort.

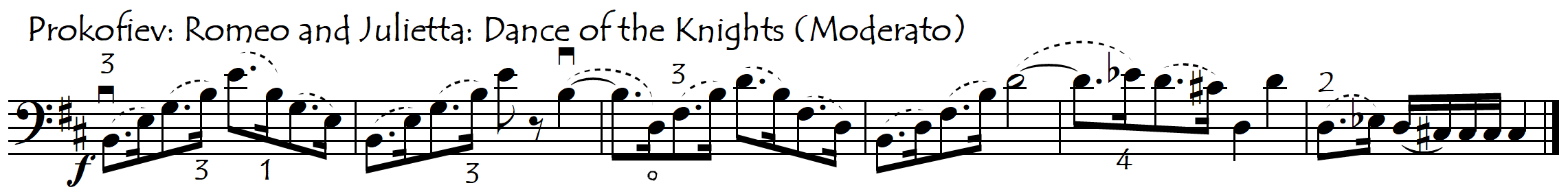

In orchestras, there is absolutely no excuse for urtext “suffocation bowings” because players in a section can change their bows at different times in the phrase without those individual changes being audible. We can even change our bow on a long sustained note without the change being heard, as in the following famous passage from musical history.

The Philadelphia Orchestra had a policy of “free bowings” for many years: each string player could do the bowings that they wanted. During that time the orchestra was renowned for its beautiful, free, vibrant string sound. This is not surprising!

Apart from the dynamics (volume), the amount of bow we need in a passage is determined by many factors, including the quality of our instrument and the acoustics of the room in which we are playing. What may be enough bow for one particular player or room, is often not enough for a different player or for a different acoustic. We need to be flexible: there is no “perfect” amount of bow for a given passage of music. But we also need to be careful, and respectful of the composer’s intentions: if we choose the moment to change our bow when the interruption is the least audible, then we are not “rewriting” the music. If however we choose our moment badly and the bowchange is heard clearly then we are rewriting the music.

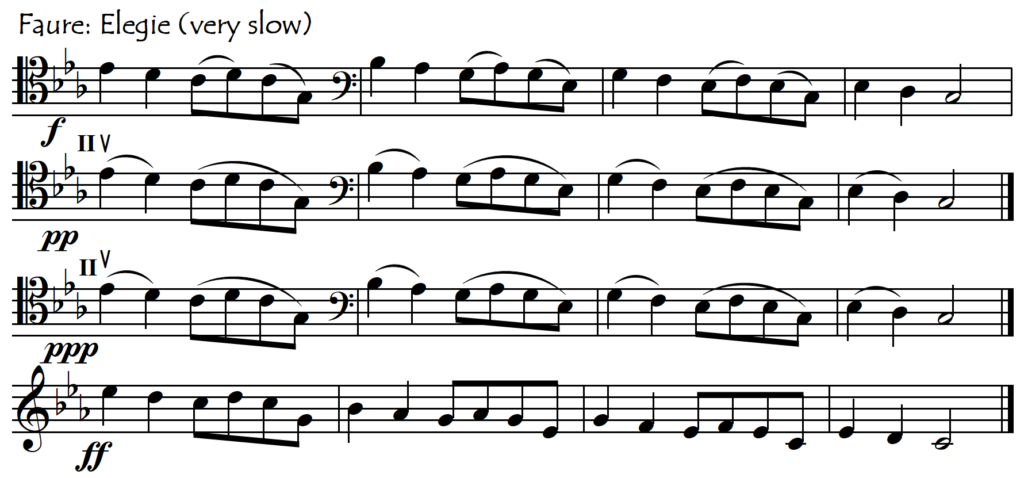

An interesting bowspeed laboratory experiment is provided by Fauré’s “Elegie”, in which the slow, legato, principal theme is played four times in very different dynamics. Fauré tries to help us by specifying the bowings. As usual, it is the soft versions that are the most difficult to play convincingly: could we use more bow in order to have a freer sound or should we do we do the opposite? Could there be a difference in the bowing between the pp and ppp versions ?

WHEN IS A BOWCHANGE NOT A BOWCHANGE?

When we change from a downbow to an upbow at the tip, especially in softer passages, the change is so easy, so smooth and so imperceptible that it often can barely be heard (if at all) as a new articulation. This is often very useful to us because instead of running out of bow (suffocating) on a long downbow that is finishing a phrase we can simply change the bow at the tip without creating any effect of breaking the line, phrase, or slur.

1:2 SLURS: PHRASING AND BOW DIRECTION

The bow has its own natural breathing cycle, just like a living being or a musical phrase. The down-bow corresponds to the expiration with its natural diminuendo and release of energy, while the up-bow corresponds to the exact opposite (see Bow Trajectory).

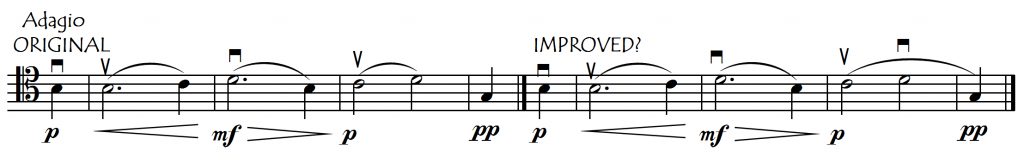

As mentioned above, slurs are very often just phrase-markings rather than bowings. Composers may know exactly how they would like their phrase to sound, but they rarely know what will work the best in terms of bowings. This means that we will often need to use our intelligence, choosing bowings that best fit the music, rather than always blindly following the score’s indications as if they were the untouchable bible. Even composers who did play a string instrument don’t always make the best bowing suggestions. The following example from Mozart’s “Marriage of Figaro” can be made much more effective and natural if we place our final diminuendo on a down bow, by changing (imperceptibly) Mozart’s slurs.

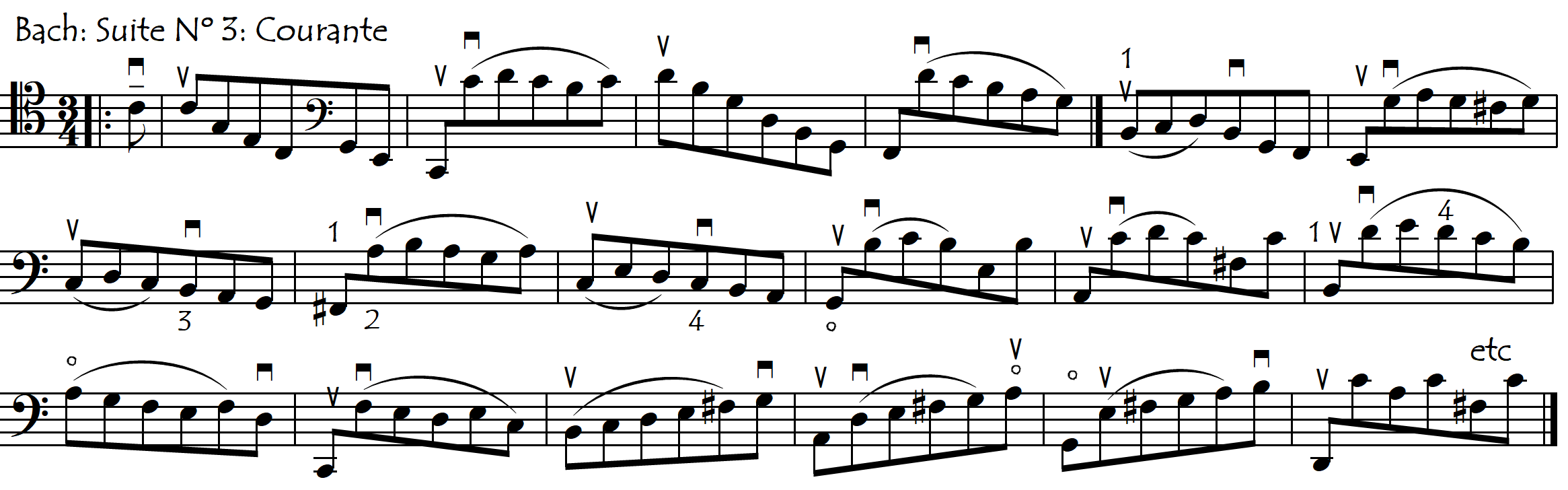

1:3 SLURS: ADDING FOR ARTICULATION VARIETY IN BAROQUE MUSIC

In Baroque music very often the “default” articulation is no articulation marking at all, and we can be faced with long sequences of notes with no slurs. In long passages of uninterrupted short notes of uniform duration, we may want to add some slurs to add variety and musical interest to the articulations. See Bach and the Sewing Machine.

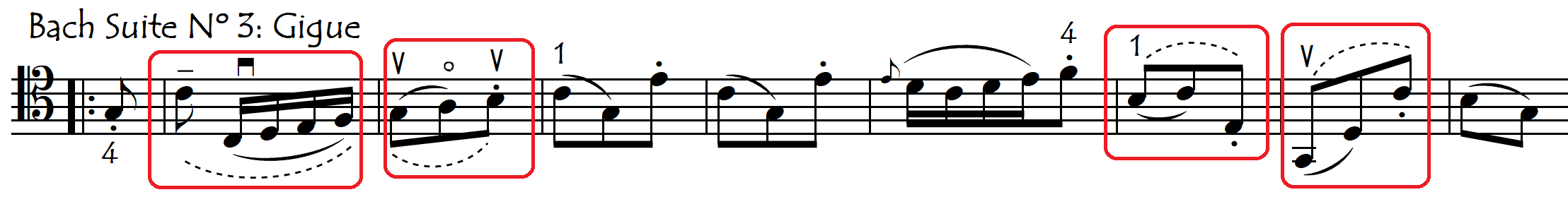

1:4 SLURS: ADDING SLURS TO BROKEN DOUBLE-STOPS FOR EXTRA RESONANCE

Another way of enhancing these same types of passage (those with many uninterrupted short separate notes) is by slurring some of the broken doublestops. Like this, we not only add interest to the monotony of unbroken separate bows, but we also gain the added benefit that, when we slur pairs of notes on adjacent strings we can let them “ring into each other” (overlap) more than if we were to play them with separate bows. This increases the harmonic resonance, the chordal sensations, and makes the music sound richer and fuller. It is especially useful in unaccompanied music. Bowing in this way, it is a little as though we are accompanying ourselves simultaneously on a second cello!

2. THE BOUNCE

Depending on what part of the bow we are using (tip, middle or frog) the “bounciness” of the bow changes enormously. The bowing we choose before a spiccato passage must leave us in the right part of the bow for the subsequent bounce because trying to do a fast spiccato in the wrong part of the bow (at the tip or at the frog) is doomed to failure.

Our choice as to whether or not we interpret the dot to mean spiccato will greatly influence our bowing choice. Dots over notes only mean “shorter” and do not necessarily mean spiccato (see Notation Problems).

3. TIP OR FROG: TWO DIFFERENT SOUND WORLDS

The different parts of the bow (frog, middle, tip) have very great differences between them with respect to weight, balance, articulation, ease of manipulation etc. The most obvious of these is the use of the frog for loud, accentuated playing and the use of the tip for smooth soft playing (and the corresponding ease of crescendo on an up-bow and diminuendo on a down-bow). A curious case that recurs very frequently – an exception to the rule of “crescendo = upbow” – is that of crescendos to a subito piano. In our choice of bowing, do we give priority to the crescendo (put it on an upbow) or do we give more importance to the subito piano (put it at the tip) ? Many people, when they see a crescendo sign, automatically will do it on an upbow if possible. This is very often a shame, as the really beautiful moment (the surprise) is the sudden piano, which is so much more tender and delicate at the tip than near the frog. It is much easier to do a crescendo on a down bow than it is to play pp at the frog.

4. STRING CROSSINGS AND BOW DIRECTION:

The natural tendency for the bow is to want to go to the lower strings on (and after) the down bow, while it wants to do the exact opposite on (and after) the up bow (see Gravity and String Crossings). When we manage to choose the bowings in such a way that the natural physical tendencies of the bow are perfectly matched to the music, then we are swimming downstream (with the current) and making life easy for ourselves. Let’s look now at some examples of this situation:

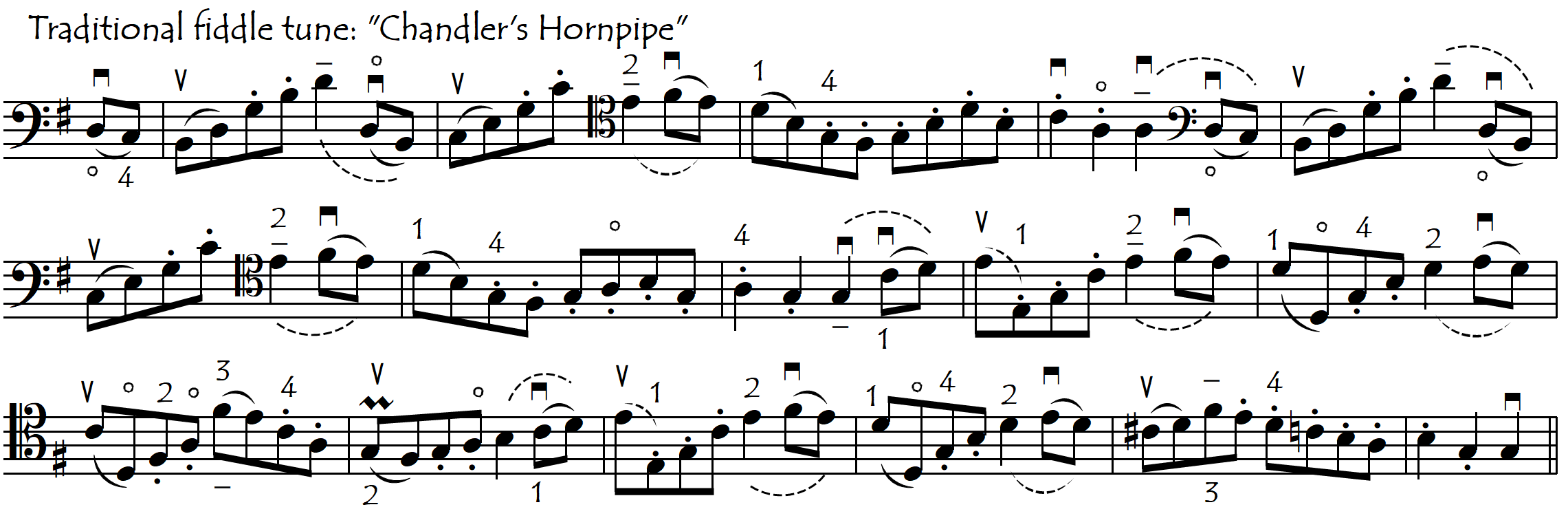

Often however, especially in faster string crossing passages, the musical factors (desire for the down bow on strong beats and on diminuendos) contradict the engineering factors (the bow’s natural string crossing and bouncing tendencies). This creates situations in which we may want (or need) to use “reverse” (or “upside-down”) bowings. Here, however, the bowings are only “upside-down” with respect to the beat, but they are “correct” according to the bow’s natural string crossing tendencies, as in the following example:

Try the above passage with the opposite bowing, to see which is easier: bowing “for the beat”, or bowing “for the string crossings”? Do the same for the following passage, from the third movement of the same concerto, in which the situation is even more extreme because the leaps are not only bigger but also faster. This makes the advantages of using the upbow on the lower string (and the disadvantages of doing the opposite) even more pronounced.

The above examples don’t leave us much room for doubt, but at other musical moments it can be less obvious which is the “best” bowing.

Even if we have a very clear idea of which bowing we prefer, very often we are unable, for various different reasons, to choose the direction that we would really like to do in a certain passage. So in any case we will always need to be able to play bowings that are “upside-down to the beat”, as well as bowings that are “upside-down to the crossings”. This subject is looked at in more detail on the following page:

String Crossings: The Bow’s Natural Tendencies

5. BOW DIVISION

“Bow division” is the complex art (or science) of planning our bowings so that we can be in the “best” possible part of the bow at every moment. This “best” part of the bow is that part where we can achieve most easily both the musical (dynamics, phrasing, legato etc) and technical (bounce, string crossings etc) requirements.

Bow division for our right hand is like ecology for planet earth: it is a huge, vital, all-encompassing subject that affects and is affected by everything. For this reason, references to it will be found on almost all the pages dedicated to our bowing. It is a complex subject because it results from the combination of all of the musical factors with the intertwining elements of bow speed, bow pressure and point of contact. It has its own dedicated page:

At the other extreme from bow division skill (choice of bowings) is bow technique skill. With a wonderful bow technique (and a great bow and instrument will also help) it can still be possible to play well in spite of bad bow division planning, by using compensations of speed, bow pressure and point of contact. It is useful to learn both skills: how to choose the best bowings ……. but also how to play the worst bowings!

5.1 BOW SPEED IN ASYMMETRICAL FIGURES

Normally we plan our bowings to avoid sudden and extreme changes in bow speed (unless deliberately needed for special effects). This planning is especially necessary for figures in which the alternation of long and short notes note creates “asymmetrical” patterns (see also Dotted Rhythms) which, without any remedial action on our part, would lead us into an unwanted, inappropriate part of the bow. In asymmetrical figures we basically have three possible choices of bowings: the retake, playing several notes consecutive notes in the same bow direction (as in hooked, portato or flying spiccato bowings) and sleight of hand. This is such a large subject that it has its own dedicated page, on which all of these alternative solutions are looked at and compared:

Choosing Bowings For Asymmetrical Figures

6. THE PULSE (BEAT) AND REVERSE BOWINGS

This is also a large subject, and has its own dedicated page:

BACH AND BOWINGS

There are so many bowing and articulation possibilities in the music of Bach that we might be tempted to wish that he had never written any bowings in his scores. Then we could be totally creative, rather than being tied to his original suggestions forever. Fortunately, in his Cello Suites, the inconsistencies in the manuscripts (none of which are in his hand) give us a certain freedom to do whatever we want, but in Bach’s violin music, his bowings are, unfortunately, very clearly specified. This is unfortunate because these indications tend to be considered as the bible: untouchable and unmodifiable if we wish to avoid being treated as blasphemous sacrilegious philistines.

How different it is when we transcribe and play Bach’s keyboard music! Here there are no (or very few) bowing/slur markings and we are therefore free to indulge our imagination, playing with the entire palette of colours of bowings and articulations that our string instrument so generously gives us. See the page Bach and Bowings for a more detailed discussion of this subject.