Articulation

In music, the word “articulation” refers not only to how we start our notes but also to how much we separate them. Whereas left-hand articulation refers to how (and when) we place our fingers on the string, on this page we will look at how we start (and separate) our notes with the bow. Articulation is all about the beginnings and endings of individual notes in contrast to “phrasing” which is about where we take groups of notes (musically) once they are already started. From the gentlest, almost imperceptible start (da niente) to the most dramatic sforzando, and from total legato connection to total separation, there is a world of articulation possibilities – a huge artistic palette – available to us. The sensitivity and variety of our note beginnings (starts) and connections is a very important factor in our interpretation and contributes greatly to the artistry of our playing.

Because “articulation” is definitely also an important component of our bow technique, this identical article can be found in both the “Bow Technique” and “Musicality and Interpretation” sections of the celloblog. Normally, however, the main difference between a fine player and a less fine player, in the area of articulations, is not a question of technique, but rather of interpretative choice. For a purely technical discussion of bow technique in note-starts see Bow Starts/Changes and Bow Trajectory from the Air.

ARTICULATION AS AN ELEMENT OF MUSICAL LANGUAGE

Articulations are not only a fundamental ingredient of our interpretation and of our bowing toolbox but are also, just like harmony, melody and rhythm, a fundamental component of the language of music. This is why this article is also included in a third department: that of “Musical Language”.

In speech, we have vowels and consonants. In music also. In speech, as in music, there are many different degrees of articulation from the hardest, clearest, most percussive starts of the letters like K, T, P (these are the ones that can spray spittle or rosin dust), to the smoothest totally unarticulated sounds of the vowels, passing through the more mildly articulated consonants of V, F, J etc. The ultimate legato (slur) for a string player is the equivalent of a singer’s sequence of changing notes on an unchanging vowel sound.

Some languages are more articulated than others. German is not only very clearly articulated but also has accents on the first syllable of most words (like Hungarian). The French language is quite the opposite: very smooth, feline and unaccentuated. Italian has a beautiful mix of crisp, clear articulations alternating with creamy legato and, moreover, a clear accent on the penultimate syllable of most words. This is why the Italian language is music: each sentence is a musical phrase, and even each word is a miniature musical phrase.

The origin of musical phrasing and articulation is in speech – and song – so it’s not surprising that the music (and cooking ??) of each culture reflects perfectly the same qualities as its spoken language. The mumbled English language often resembles not only mashed potatoes, mushy soup and mushy vegetables but also seems to be reflected in the dense, thick, gooey, sloshy textures of a lot of post-Baroque English music.

ARTICULATIONS AND DYNAMICS

Surprisingly, the way we start (articulate) a note is quite independent of its dynamic. A pianissimo note can start with a crisp, clear attack and vice versa, a forte note can start smoothly. To use the speech analogy again, we can whisper the word “piano” with a very percussive start or we can shout the word “no” with a very smooth unarticulated beginning.

MAKING NOTE-STARTS VISIBLE

There is an excellent, free, computer program for audio recordings called Audacity. On any computer, we can record ourselves and then look at the “image” of the sound. If we zoom in on some of the note-starts, we can see perfectly how the abruptness of the start and the rapidity of the decay (fade-out, fall-back) correspond to the degree of articulation.

WHEN THE LEFT-HAND HELPS THE RIGHT-HAND’S ARTICULATION

Very often, we will have the left-hand finger already prepared on the string before the bow starts playing the note (see Preparation Principle). In these cases, the manner in which we start (enunciate) each new note is decided solely by the right hand/arm. But in certain other cases the left hand also can contribute to the bow’s articulation impulse, while in other cases it is only the left hand that determines the type of articulation that we give the note, as explained in the following cases:

1. LEFT-HAND ARTICULATION (HAMMERING) IN A SLUR

In a 100% legato slur, it is uniquely the left hand that determines the clarity of the articulation, according to the speed and force with which the fingers are placed onto (or lifted off) the strings. The faster the passage, the more we need to articulate clearly the left-hand fingers, for which we may prefer to use the harder tips rather than the softer pads (see Finger-String Contact and Finger Articulation). In staccato and portato bowings however, the pulsations within each bowstroke also contribute to the articulation.

2. LEFT-HAND PIZZICATO TO HELP WITH BOW STARTS ON OPEN STRINGS

Often, it can be difficult for the bow to get the open strings cleanly vibrating at the very beginning of the bowstroke. Open strings often scratch at the start. This is because the open string is “stopped” by the ridge (nut) at the top of the fingerboard which is much harder and more abrupt than when a note is stopped by a finger. To start the string vibrating before the bow starts (or simultaneously) we will often use a discreet Left-Hand Pizzicato.

3. SFORZANDO ATTACKS: THE DOUBLE WHAMMY

For extra emphasis, especially in loud sforzandos and accents, we might want to hit the string with both hands at once. This not only looks dramatic and exciting but also helps to avoid a possible scratch on the sfz bowstart. Perhaps the soloist’s first entrance in the Dvorak Concerto could be a candidate for using this little special effect.

ARTICULATION AND BOWINGS

Often, our bowings (choice of bow directions) are determined by the articulations that we wish to obtain. While a slur gives the ultimate degree of minimum articulation (maximum smoothness), spiccato, “hammered” and “flicked” give the ultimate degree of maximum articulation (separation). In between these two extremes, following the progression from minimum to maximum articulation, are portato, separate legato, and detaché (literally “detached”) bow strokes.

Whereas it is the composer (most often) who specifies the desired articulations, it is we, the players, who have to organise our bowings (choice of bow directions) in such a way that we will be in the right part of the bow to be able to achieve these articulations. For example, gentle starts are easier further away from the frog, spiccato needs to be in certain parts of the bow etc (see Choosing Bowings). Some composers don’t specify much in the way of articulations. This doesn’t usually mean that there should necessarily be little variety in articulation, but rather gives the player free rein to use their imagination. This situation occurs especially in Early Music as well as in Folk and Popular music of all periods.

Bach – especially his Suites for Solo Cello (but also in his Partitas and Sonatas for Solo Violin) – is the most challenging music intellectually for choice of articulations. This is because of the combination of an enormous number of notes to play (with very few long, held notes but many short faster notes often in quite repetitive rhythms) with an almost complete absence of valid bowing and articulation instructions. This means that a large part of our interpretation of Bach’s music is simply a question of choosing the bowings and articulations that give form, sense and meaning (as well as making it technically easier to play) to music that could otherwise sound quite minimalist. Part of the huge variety of completely different Bach interpretations out there is largely due to this enormous freedom given us by Bach’s lack of articulation instructions.

We can find some very good examples to illustrate this in Bach’s Partita in B minor for Solo Violin (here transcribed for the cello). In the second Double, there are 960 notes (if we don’t play the repeats) of which only 3 are not semiquavers. Only 30 of these notes (3%) are slurred (according to most editions). In the third Double, there are 183 notes of which only 2 are not quaver (8th note) triplets and there are absolutely no slurs. Adding slurs in the appropriate places (as well as using lots of Phrasing and Rhetoric) is one way to avoid these pieces sounding like minimalist sewing machines.

To clearly show the importance of “articulation” in the language of music, we can try playing any piece of music with no articulation variety: no slurs, no staccato, no spiccato. Alternatively, get Finale or Sibelius to playback some music with all the articulation signs removed.

SHORT UPBEAT SEPARATED FROM LONG DOWNBEAT ? NOT ALWAYS !!

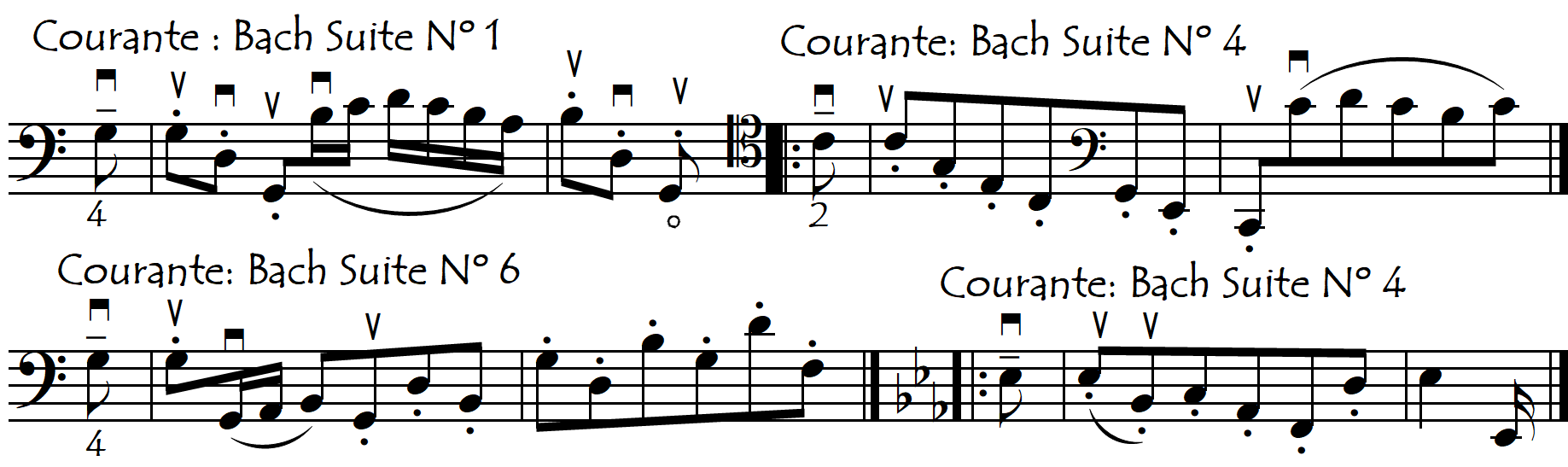

While the short upbeat, separated from a longer downbeat, is certainly very common, sometimes we can use our imagination and do exactly the opposite. For example, in the Courantes of most of the Bach Suites:

THE DOT

Never was such a simple sign used in so many different and ambiguous ways! When placed on (or under) a note it means short or separated, but this separation can be with respect to the note before, the note after, or both. The dot is looked at in greater detail in the “Reading Problems” article.