Music Reading-and-Notation Problems

Fluent music-reading (the decodification of the musical notation) is a complex skill, acquired and perfected only by many years of practice and experience. Learning music without reading it – by ear and/or by simply copying at the instrument – is the time-honoured way in which music (and all other knowledge and skills) was transmitted until the discovery of written forms of communication. The notation of music – as with the writing down of any language – is an evolutionary step forward from personal transmission in the sense that it is a much more efficient way of mass-propagation and preservation of musical compositions.

However, while music-reading is undeniably a hugely useful skill – and totally necessary for a classical string player – we should be aware that it can create certain specific problems that people who play by ear (or from memory) don’t have. Many great musicians – both composers and performers – have been almost or totally “illiterate” with respect to the writing and reading of music: The Beatles and Luciano Pavarotti, along with a huge number of rock/pop musicians come immediately to mind. And the extraordinary young cellist Santiago Cañon was already an instrumental virtuoso before he could properly read music.

Before looking in detail at some of the problems that can be created specifically when we read music, let’s look at the subject of how we actually “read” music ?

As instrumental musicians, we have two overlapping possibilities:

- we can read music “aurally”, like singers, translating the written code into its musical intervals and rhythms. Reading in this way, we are imagining (sounding, singing) the music in our head as pure (vocal) music with no attempt to play it on our instrument, neither imagined nor in our hands. This is “sight-singing”, a purely intellectual skill, requiring no emotion and no bodily motion. This is a very difficult but very useful skill, equivalent to (but much more difficult than) reading a book silently to ourselves.

- we can also read music “instrumentally”, translating the written code directly into the physical movements necessary to make the sounds rather than first imagining those sounds aurally. We can do this almost as well while simply imagining ourselves at the instrument as when we actually have the instrument in our hands. This is the equivalent of reading a book aloud, except that it is, just like for sight-singing, also much more difficult. The added difficulty comes from the fact that, for reading music, we not only have to decipher the pitches and the rhythms but also we have to calculate how to play them on the instrument. So for each note, not only do we need to decipher its pitch and length but also decide (choose) on which string we will play it, which of our five fingers we will use, what part of the bow we will be in and in which bow direction. We can easily understand why sight-reading makes high-speed chess look like a sunday stroll ! Reading music is infinitely more complicated than reading words because for words, not only are the pitches and rhythms unspecified but also the physical aspect of our sound (voice) production is completely automatic, requiring no thought or calculation.

Let’s look now at some of the possible problems that can be associated specifically with the reading of music, as compared to when we learn it and play it by ear:

1. READING TAKES UP BRAIN-SPACE AND THEREFORE TAKES AWAY FROM MUSICAL EXPRESSION AND BODY-AWARENESS

Written music is a very complex codified language. Learning to read music (decode it) takes an enormous amount of time and practice. In fact, when learning a new piece from a written score, it is the reading, the decodification of the written score, that can actually take up most of our concentration. This can be so even for a professional musician but is especially true for a person who is not yet familiar with this written language.

One of the most wonderful things about the Suzuki method of instrumental teaching is that the “reading” aspect is left till later. This allows the learners to dedicate their attention to their body-use and to the musical expression. This is a very good habit to get into from the earliest age as the complications of reading often distract even professional musicians from giving attention to body-use and emotional expressivity. And body-use and emotional expression are not just the two most important elements of music: they are music. Reading music is not making music – it’s only giving us the instructions. Even when we know a piece of music well, reading the score while playing not only takes up brain space that could otherwise be used in our playing but also keeps us anchored in the here-and-now when we could otherwise be flying in a deep imaginary-sensory world with our eyes closed.

Sight-reading music is quite different to reading a piece that we already know. In fact, we only really read music carefully when we don’t know it. Once we know how it goes, even if the score is in front of us we use it mainly just as a reminder of what’s coming and to prevent ourselves from getting lost. Our aural and physical memory at the instrument is much better than our aural reading ability, and once a piece is “in our head” we only need the written music to activate (trigger) that memory.

It is possible to be a very good, quick reader while at the same time being a not-very-good instrumentalist and/or a not very expressive musician, because pure reading is a very intellectual skill. Conversely, it is possible to be a wonderful instrumentalist and musician without knowing how to read or write music at all, as the Beatles illustrated perfectly. Not surprisingly, musicians who don’t know how to read music usually have a much better memory for it and often are more spontaneous and expressive performers. Many wonderful singers are not very good music-readers – Pavarotti was a good example – however it is of course possible to be a great reader as well as a great instrumentalist and musician.

We have talked about the “Tyranny of the Thumb” with respect to the left-hand (see Left Hand Regions). We can equally well talk about the “Tyranny of Reading” with respect to classical music in general. Both the written score and permanent thumb contact give us security but at the price of freedom and expressivity. In both cases, it’s “safer with, but more fun without”.

One way to not let the reading aspect detract from the musical and physical aspects is to do the initial reading stage away from the instrument. This is surprisingly useful. We can learn the rhythms, plan our fingerings (maybe also the bowings), and can advance significantly in our learning of the piece – and all that without any physical or emotional tension. Doing this while listening to a recording of the piece is even more useful as we are using here elements of aural transmission (learning by ear). Needless to say that if we do this with the full score in front of us rather than just the cello part, our understanding of the piece will benefit considerably.

2. READING REDUCES CREATIVITY

When we play from a written score, we tend to follow the instructions rather than using our imagination. When we play however from memory, we soon forget the original notation (unless you use photographic memory) and start to play with more creativity, ultimately not only forgetting certain indications but perhaps even changing them. We begin to play more spontaneously and freely, as though we were improvising rather than just following instructions …….. hopefully!

Actors have much fewer instructions in their written parts. This makes their interpretations more varied and interesting, not only between different actors playing the same role, but even for the same actor on different days. This is a more interesting creative activity and much more satisfying for the performer (and for the public who might have heard the same piece many times). See Sing or Speak? and Freedom or Obedience

3. THE DANGERS OF READING TOO LITERALLY

Music is usually played only after being first written down (by the composer) and then read (by the player). That means that between the composer’s imagined aural idea and our performance, there are two stages of transmission via the written notation: the codification (writing) and the decodification (reading). In both these stages, information can be excluded, forgotten, lost, scrambled and approximated.

Written music is a code that is, at the same time very complex and not very exact. Because of this, it requires a lot of experience and knowledge to interpret all the information musically. If we interpret some elements of the notation too literally we can fall into various technical (instrumental) and interpretative traps which we will discuss separately here.

Let’s look first at some of the technical traps caused by reading too literally:

3.1 TECHNICAL PROBLEMS PRODUCED BY READING TOO LITERALLY

3.1.1 LITERAL READING TECHNICAL TRAP Nº1: NO TIME FOR SHIFTING

Musical notation does not allow for the time it takes to do a shift. In a literal interpretation of the written music, the shifts in a legato passage would be “infinitely fast” in order to be able to hold the note before the shift for its full value (length) and also start the note after the shift in time. This is of course impossible, and leads unwary, obedient people to try to do shifts both as-late-as-possible and as-fast-as-possible. This makes playing the cello VERY difficult, is a recipe for disaster in every sense, and is absolutely the opposite of what we need to do. (see Shifting)

3.1.2 LITERAL READING TECHNICAL TRAP Nº2: BOWINGS OR PHRASINGS?

Very often, especially in Romantic music, a composer’s phrasing markings (slurs) are misinterpreted to mean “bowings”. This almost always leads us to try to play with bow-strokes that are excessively long, leading to a strangled or, at best, unexpansive sound in which bow-pressure is overused as a sound-production mechanism in relation to bow-speed. It is very hard to play expressively under these conditions. A bow change is not the equivalent of a singer’s new breath, and can be imperceptible, especially a change from downbow to upbow at the tip of the bow. This is not to say that practising with long slow bows is not a very useful yoga-like exercise to develop control: it is. But suffocating a musical phrase in order to fit it into one long bow-stroke is usually due to a misinterpretation of the composer’s phrasing indication and is seldom worth the effort.

Mozart was a string player and most of his slurs are exactly that: bowings. But Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Beethoven and many other composers, especially of the Romantic era, were not string players and their “slurs”- especially the long ones – are very often indications of phrasing rather than bowings (see “Choosing Bowings“).

Going back to the urtext score to discover the composer’s original intentions is almost always a good idea, but even some of the world’s finest cellists/musicians, in their desire for authenticity, can fall into the unfortunate trap of considering phrase markings as slurs.

Now let’s look at some of the interpretative traps:

3.2 INTERPRETATIVE TRAPS CREATED BY READING TOO LITERALLY

3.2.1 LITERAL READING INTERPRETATIVE TRAP Nº 1: NO RUBATO OR PHRASING

Only the most extreme tempo and dynamic changes are indicated in musical notation. We have to allow ourselves the freedom to invent all the small, humanising details of rubato (tempo changes) and phrasing (dynamics) in order to make the difference between a living, breathing, spontaneous, communicative, human, exciting, moving performance and the dull, square, utterly predictable, mechanical, metronomic rendition that would result from doing exactly as the written score says. See Freedom or Obedience? and Sing or Speak?

Sometimes composers write “ad-lib” or “cadenza”, notating the music without barlines and with smaller noteheads. Here, it is clear that we have permission to do exactly as we please rhythmically. But between this extreme and that of the other 99% of our music that is notated with standard rigid rhythmic-and-barline structure, there is a whole world of graduation possible. One of the best examples comes at the entrance of the soloist in the Beethoven Violin Concerto. Most violinists play it “like it’s written”, so hearing Wanda Wilkomirska play it as though a living creature was gradually waking up (or unfolding) was an interpretative revelation as to the power of NOT playing exactly what is written!

3.2.2 LITERAL READING INTERPRETATIVE TRAP Nº 2: PROBLEMS IN READING (UNDERSTANDING) RESTS

According to a literal interpretation of written notation, rests are silences in which “nothing is happening” and “the music stops”. Pinchas Zukerman is not in agreement and has this to say …..

“in music, rests don’t exist ….. the music doesn’t stop until the piece has finished …… rests are just breaths (pauses) during which the musical intention continues …..”

“Rests” are actually very well named: their descriptive title implies an opportunity for a little rest-and-relaxation (and breathing for singers and wind players), but does NOT imply silence. In an ensemble, other people are probably playing during our rests, and even in unaccompanied music, a large part of most rests is taken up either with the resonance of what has just been played or the anticipation (“pregnant silence”) of what is about to come.

When we have a “rest” in our score during a piece of music, this is not an opportunity to check our phone, clean our strings, fix our buttons or do something else. And when we transcribe vocal or wind music for any string instrument, we may decide to shorten or even eliminate some of the “breathing rests” that we string players don’t need (see “Morgen” by Richard Strauss).

Sometimes we musicians can be tempted to give importance only to the aural aspect of our music-making and think therefore that we can do anything we like while we are not playing, so long as we remain silent. But in fact, we are in many ways like actors. Actors, unlike many musicians, are well aware that, as long as they are on stage, even when not saying any lines, their every movement and gesture is either a contribution to or a distraction from the drama that is unfolding.

3.2.3 LITERAL READING INTERPRETATIVE TRAP Nº 3: LACK OF IMPROVISATORY MELODIC FREEDOM

“Improvisatory melodic freedom” refers to those liberties taken exclusively with the melody line, while the harmony and accompaniment continue without any variation. With rubato and phrasing, we play what is written but with more freedom, adding unwritten rhythmic and dynamic expressive nuances to the score. Melodic improvisation however takes this freedom one level higher, involving actual changes to the pitches or rhythmic values of the notes. Here, we are considering the written score as a rough outline, a guide, a sketch, to be modified and/or filled out according to the imagination of the performer.

There are two main types of melodic improvisatory freedom: the addition of ornaments, and the “rewriting” of the rhythms. Let’s look first at the rhythmic modifications

3.2.3.1 REWRITING OF RHYTHMS

SWING, POP AND JAZZ:

A good example of this need for rhythmic melodic freedom occurs in “swing music”, as well as in pop and jazz. Here, even though the rhythms are usually notated as “simple, square, on the beat” and in 3/4 or 4/4 time, they must usually in fact be played syncopated and in compound time (with triplets instead of hard, crisp dotted rhythms). Playing this music exactly “as written” will make it sound childlike or square, formal and uptight. (see Fascism in Music). In fact, almost all “popular” music, especially from jazz onwards but also folk music of all times, is full of syncopations, triplet rhythms, and possibilities for melodic improvisatory freedom. This music is however normally notated (written out) in a simplified 4-square way as in this example of “Yesterday”.

This “simplified notation” actually has two very positive effects:

- it avoids the written parts looking incredibly complicated (syncopations and jazz/pop rhythms are usually easier to feel than to read).

- it opens the door to a wide variety of different types of improvisatory rhythmic freedom (if the music was written out exactly, with all the syncopations, triplets etc. it would become harder to do anything different).

But we musicians must be aware that sometimes, music is not to be played as it is written !! “Yesterday” could be played freely in many different ways. Here below is perhaps one of the possibilities:

A “wandering” melody over a rhythmically stable accompaniment is a very powerful, expressive and deeply philosophical “device” with its tantalising combination of freedom with discipline, liberty with responsibility, individualism with social awareness. It is the equivalent of “writing between the lines”, “thinking outside the box”, “dreaming while anchored in reality” ……… etc.

“A L’ITALIANA”

Another example of when we might deliberately not play the notated rhythms occurs in a lot of Italian music, where the magic words “a l’italiana” automatically mean that we should play the short notes – usually upbeat figures – both later and shorter than notated, giving that crisp “al dente” italian sparkle to the music, which is oftentimes notated in stodgy four-square unsparkling rhythms. The literal reading of the rhythms here will not impress anyone. We may choose to do this “a l’italiana” tightening even in purely melodic figures (see the cello opening to Rossini’s “Una Voce Poco Fa” and the start of his Duo for Cello and Bass).

“A LA FRANCESA”

This implies the identical rhythmic transformation as in “a l’italiana”, whereby we convert all dotted rhythms into double-dotted, in order to give the same crisp, energetic style so characteristic of the french baroque overtures. Remember that one of the most famous french baroque composers Jean Baptiste Lully, was in fact Giovanni Battista Lulli, born and bred in Italy!

3.2.3.2 ORNAMENTATION

FREEDOM TO DECORATE

How beautiful it is to hear the repeated section of a Late-Baroque (or Early-Classical) piece elaborated with well-thought-out ornamentation! The ornamentation of a repeated section is, however, normally not notated by the composer. If you haven’t yet heard Christophe Coin’s Vivaldi Cello Sonatas (or Rachel Podger’s Mozart Violin Sonatas), you have an enormous pleasure to look forward to and a perfect illustration of the delights and expressive power of un-notated ornamentation!

When ornamentation is notated it is sometimes more complicated than when we are left to improvise it. Now we must try and interpret the composer’s instructions and this can be a tricky business because of the ambiguity of the notation. Let’s look at some of these situations:

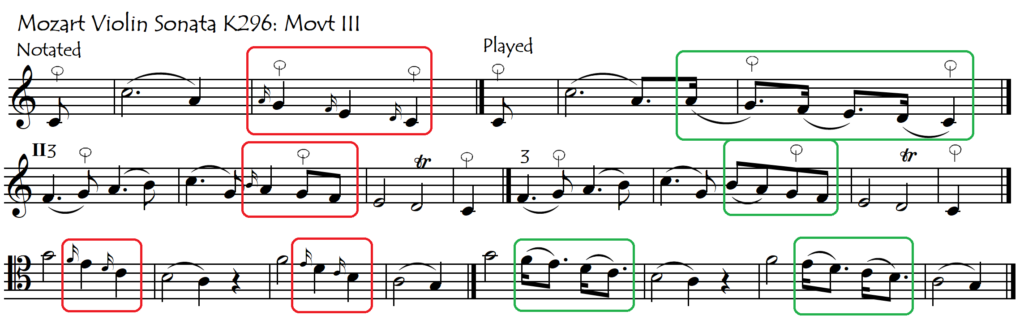

GRACE NOTES

The notation of grace notes is very often quite ambiguous. That same little grace note, notated before the principal note, can be played either before the beat or on the beat. It can also be played in a variety of lengths anywhere between very short and very long. The following examples from Mozart’s Violin Sonata K296 illustrate some of these possibilities:

TURNS

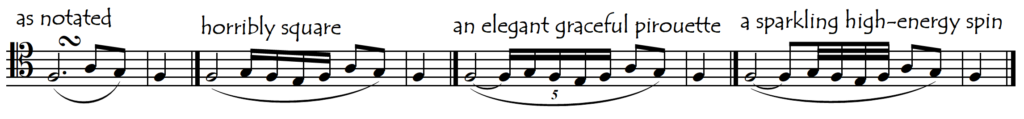

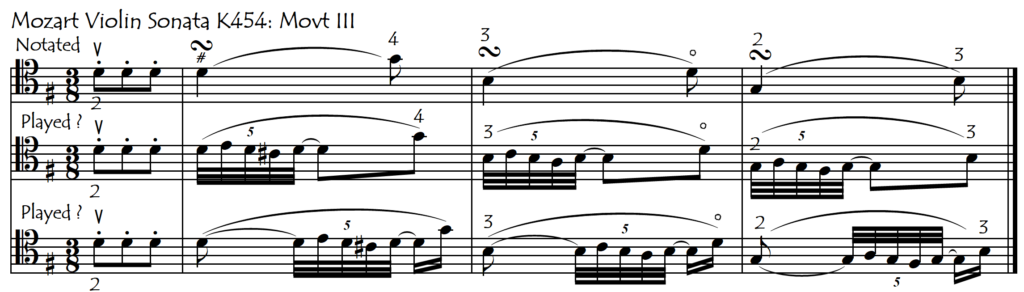

Working out the best rhythmic placement for the notes in a turn can be a real juggling act (or jigsaw puzzle) which can have quite a notable effect on the success (or not) of our interpretation. We usually want our slower turns to sound like beautiful ornamental dancing gestures rather than mathematically precise pieces of engineering. One of the best ways to achieve this effect is to use quintuplets in our turns, often with the first or last note of the quintuplet tied to the preceding or following beat. None of this is of course indicated in the notation symbol:

Even if we decide to make a quintuplet turn, we can still sometimes have some doubts about where exactly to put the quintuplet notes:

3.2.4 LITERAL READING INTERPRETATIVE TRAP Nº 3: MECHANICAL BEGINNINGS AND ENDS OF NOTES

Musical notation is binary: the note is either “On” or Off”. Musical notation doesn’t enter deeply into the world of different gradations that is possible at the endings and the beginnings of the notes, nor does it enter into the world of resonance, where the music keeps sounding (because the string and instrument keep vibrating or because the hall keeps resonating) even though we have taken the bow off the string. We have a considerable margin of choice as to both the “how” and also the “when” of our note beginnings and endings.

NOTE ENDS: Unlike what the notation “says”, the great majority of notes are not maintained evenly (sostenuto) for their full value, especially in Baroque and Classical styles. In fact, many notes are not maintained for their full value at all. The bow stops pressing earlier than the notation says, leaving only the resonance, an “almost silence”, a breath, before the next note. (example).

NOTE STARTS: In slower playing especially, many notes actually start progressively with a “fade-in”, rather than with a mechanical On-Off start. This gradual start begins slightly before the beat and can concern both volume (fade-in) and/or pitch (glissando). (example)

Between a silence and a written note, there exists a whole range of sound possibilities that we can invent and play with. Realising this and taking advantage of it contributes enormously to our expressive palette.

3.2.5 LITERAL READING INTERPRETATIVE TRAP Nº 3: DYNAMICS

Einstein’s Theory of Relativity may be a Law of Physics but Einstein himself declared that his theory was inspired largely by music. (See Why Learn Music?). In music, everything is relative, and dynamics are no exception. A dynamic marking is never an absolute volume level but is rather entirely relative: to what has come before, to what will come next, and to what is going on around you. The actual volume (measured in decibels) that we need to produce, especially in a passage marked “p”, will vary enormously according to the musical and acoustical circumstances. That very same “p” will need to be much louder when accompanying a large choir in a huge hall or playing a section solo in a large orchestra as compared to when playing string quartets in a small room.

Especially in orchestral music, when composers write “p” this is very often not a reference to how loud we need to play but rather is a reflection of the volume (decibel level) of the music at that moment. When a large noisy tutti passage full of brass, winds and percussion is followed by a reduced-formation string passage, the composer will usually write “p” but if we actually play it “p” then nobody will hear it. Even if we play it “f” the total decibel level will still sound soft in comparison to the full tutti orchestra and the global “p” effect will still have been achieved. This would be a fascinating subject to explore with a sonometre.

Many excellent examples of this common phenomenon can be found in the tone poems of Richard Strauss where a very common effect is large forte tutti is followed by a solo passage for the cello section divided into pairs of players (desks), each with a different part and whose interventions are marked “p”. If we play “p” as marked the effect is more that of the “p” in pathetic, whereas even if we play a minimum of “mf” then the sound level is only starting to approach the level of a full-orchestral “ppp”. For an audience, the most successful concert option is actually to play “f” in these passages !

Even in the orchestral music of Mozart, this same problem exists quite commonly. In his overture to the opera “The Abduction from the Seraglio” after a loud tutti opening, the cellos (without the doublebasses doubling us underneath) have an energetic theme that is marked “p”. Once again, even if we play a minimum of “mf”, the music will still sound “p”. And in his Serenata Notturna for strings and timpani, high-energy interventions of solo string players between the loud tuttis are also marked “p” but are definitely not to played “p”.

3.2.6 LITERAL READING INTERPRETATIVE TRAP Nº 4: STACCATO ARTICULATION (DOT).

The simple “staccato” dot over (or under) a note is a very ambiguous, approximate instruction, meaning quite different things in different musical circumstances. The dot implies “separation” and “shortness” but between the two extremes of the driest (shortest) spiccato to the very slightest “portato” separation (pulsation), there exists a whole world of graduation possibilities. The different interpretations of “the dot” concern not only the amount of separation (degree of shortness) but also on which side of the note this separation must come: the dot can mean a separation from the preceding note, from the following note, or both.

The first of the above examples illustrates a very common situation in which this ambiguity can often cause problems. While the dot on the “short note” ( the “E”) refers to its separation from the preceding note, the dot on the following note (“G”) refers simply to its shortness (which means its separation from what comes afterwards) and not to any separation between it and its preceding note. So, even though both notes are dotted, there should in fact be no separation between them. Yes, this is definitely confusing! When computers see this notation, they automatically play it with a separation between the two dotted notes, but this sounds horrible, especially at faster speeds. Here, instead of gentle Viennese lilting flow, we are entering into Monty Python’s Silly-Walk territory! Fortunately, we have better taste than computers, and can hopefully understand intuitively that the interpretation of a dot does not always follow a standard rule. Certainly, it would be easier if the dot always implied a separation from what comes afterwards, as shown in the first alternative solution. This would mean that any note with a dot is shortened, without any ambiguity. Another possible solution to these dotted-doubt situations could be provided by the use of rests instead of dots, as shown in the second alternative solution.

Just like in the above example, it is very common that in dotted rhythms, the short note might have a dot on it. This almost always means that it is the note before the little note that must be shortened, in order to make a separation between them. This certainly is a strange coding (notation) system, in which it is not the note with the dot on it that needs to be shortened, but rather the preceding note! Here is another example of this from the music of Fritz Kreisler, with the preferred cellofun notation alternative shown afterwards:

To avoid confusion and ambiguity with regard to the interpretation of the staccato dot, in the cellofun editions the articulation notation has normally been changed for these types of figures. Now, instead of dots at the end of slurs, we prefer to use dashed slurs with no dots. The dashed slur automatically implies a separation between the two “slurred” notes. The elimination of the dot also eliminates the possibility that we might try to separate the little dotted note from its following note, which would not only sound bizarre but also would be rather difficult.

Even with this effort to eliminate ambiguity and standardise the meaning of the staccato dot, there are still notation situations that defy easy solutions. Once again the music of Kreisler will be used as an example:

Here, we want the second note to be short, but connected legato to the first note. But how can this be notated ? An exact notation (bars 3-4 and 5-6) is very laboured and cumbersome but putting a dot on the second note can make us want to separate it from the preceding note (which is wrong). So there seems to be no ideal notation for this figure and it is simply assumed that we understand the musical language sufficiently that we will know, automatically, that in this style of music, the second note of a slurred pair is always shortened.

Also very susceptible to ambiguity are dots under a slur. In fast virtuoso music, these dots usually imply the extreme shortness of flying staccato or ricochet. However, in slower or moderate-speed music, dots under a slur usually imply the exact opposite: here we normally want the dotted notes to be less separated than they would be if each note was to be played on an ultra-legato separate bow. So in fact, dots under a slur very often mean “portato” – but are often interpreted erroneously to mean “very separated” (staccato, spiccato or ricochet). The examples shown here below illustrate this confusing way in which portato passages are often notated:

In a perfect world, those portato-dots under a slur would be changed for lines or, for slightly more separated notes, lines with dots. Both of these signs would make their portato articulation unambiguous:

3.2.7 LITERAL READING INTERPRETATIVE TRAP Nº 5: ACCENTS, FORTEPIANOS AND SFORZANDOS

There is great confusion and ambiguity in the way composers indicate accents. Theoretically, an fp has a faster and more extreme volume reduction than a typical “accent” and an sf or sfz is somewhat more brutal and takes the longest time to become softer. But often these indications are interchangeable.

Basically, every composer has their own personal way of using and indicating accents, in the same way that every person has a different way of accentuating their speech patterns. A Brahmsian fp (as in the above example) is nowhere near as quixotic and nervous as a french impressionist fp, and Schumann and Schubert’s fp’s and sfz’s, especially in their slow movements, are usually infinitely more gentle than Beethovens. In fact, accents, fp’s and sfz’s in slow, soft music by Schumann and Schubert are mainly done with a momentary increase in vibrato speed and intensity, with perhaps just a little gentle surge with the bow.

It is not surprising that an accent sign looks exactly the same as a very short diminuendo hairpin because, normally, that is exactly what it is. We can see this especially clearly when an accent (or fp or sfz or sf) is placed on the first note of a (fast) group of notes, as in the above example. Rather than the accent only being played on the first note of the figure, it is often spread (distributed) across the first few notes and is actually like a quick diminuendo.

And, as a final observation about the reading of accents, an accent can sometimes also mean “take more time” as well as “give a stronger articulation”. The above example is also a perfect illustration of this double-meaning: not only does the first triplet figure have a diminuendo but it also has a big rubato, starting slower and heavier and then speeding (and lightening) up. Now the music really starts to feel like “Brahms”.

********************************************************

Some “reading traps” are dangers to both our interpretation and our technical execution.

3.2.8: LITERAL READING INTERPRETATIVE AND TECHNICAL TRAP: DOTTED RHYTHMS:

Visually, in music notation, the short note that comes after a longer dotted note “belongs” in every way to the note that comes before it: not only is it usually beamed to the preceding note but also it belongs to the same bar (measure). This is unfortunate because, in fact, those little notes normally “belong” much more to the notes that follow them rather than to the notes which precede them, in exactly the same way that an upbeat “belongs” to (and is the start of) the new phrase. Thinking (unconsciously) that the short note belongs to the preceding note not only gives rise to interpretative (phrasing) errors but also leads us to use inappropriate (more difficult) fingerings. We can make it so much easier for our left hand if we finger the short notes so that they are already in the same position as the following note. In that way, we can shift after the long notes, which is when we have the most time (see Technical Fingerings and Shifting).

CONCLUSION

Unfortunately, many of us classically trained musicians try to play all music “as written” (literally). That is hardly surprising seeing as such a large part of our training is simply to “read and follow every instruction perfectly”. Playing from memory and learning by ear (or by copying), protects us from falling into many of these “notational traps” but seeing as we will inevitably have to play often from written parts, we must also, ultimately and inevitably become good “readers”. This of course means not only “reading exactly” but also knowing when to read inexactly, “between the lines” of the written notation. This is a very large part of the process of becoming a musician.

*************************************************************************************

MUSIC PUBLISHING AND EDITING: HOW TO MAKE READING EASIER (OR HARDER)

Even the most simple music can be written out in a way that makes it very very difficult to read. Let’s talk now about ways in which a written score can be made more (or less) user-friendly, or in other words, how a score can be made easier (or more difficult) to read.

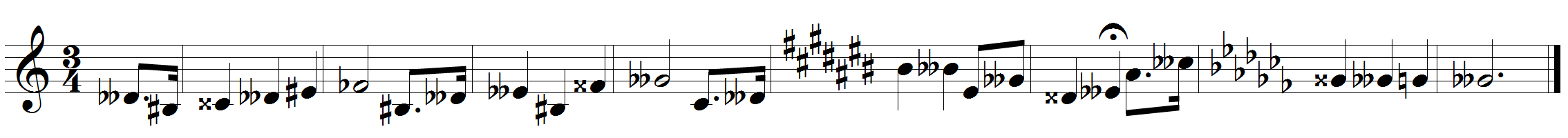

Try reading the following examples, away from your instrument:

In the above examples, it is the choices of notation for both pitch and rhythm that are responsible for the extreme difficulty of the reading. These examples show just how much the way in which music is notated can influence the ease (or difficulty) with which it is read, but they also show how easy it is to play these “extremely complex pieces of music” (?!) once we have first “worked them out” (decoded the notation).

Some musical passages may be complex for both the reading and the playing (see the sections on Ear Training and Rhythm), but the problems in the above examples are exclusively in the reading. And of course, there are other musical passages that are very easy to read, but very hard to play. The problems of notating/reading pitches and rhythms are discussed and illustrated in more detail, with standard repertoire examples as study material, on their own separate pages:

The way in which the pitches and rhythms of a piece of music are notated are almost always decided by the composer and it would take a brave editor to dare to “improve” on the composer’s choices in order to make life easier for the players. But music publishers and editors do have a lot of influence in making a score more (or less) easily readable without touching the notation, simply through their layout and printing choices.

MULTIMEASURE RESTS

Counting bars (measures) of rests is a totally unmusical activity. When we are counting rest bars we are absorbed in a totally mathematical world in which our only priority is not to lose count because if we do, the consequences can be catastrophic. In this situation, the music that is playing around us can even be a distraction and cause us to lose count, especially if there are complex rhythmic effects and/or phrasings. Apart from knowing the music well, reading cue notes, or counting phrases, are both much more musical ways to keep our place in the score when we are not playing. So, rather than trying to count a large number of consecutive bars of rests we (or the music publisher) could divide that non-playing time into a certain number of musical phrases, with the addition of cue-notes to orient us at the tricky moments. In this way, we could avoid not only the stress and the danger but also the unmusicality of counting bars when not playing.

MODERNITY AND THE EASE OF COMPUTERISED LAYOUT

In the past, music publishing and printing was an expensive, complex and laborious task, so it is no wonder that so many “standard” editions of the music that we play – especially early 20th-century orchestral parts – are so awful to read from. The instrumental and intellectual difficulties of the orchestral works of Richard Strauss are made infinitely worse by the unnecessary reading problems that these deficiencies create. Nowadays, thanks to computers and programs like Finale, Sibelius etc, music publishing and layout are very simple tasks, although the learning curve is quite steep. Once the music has been “computerised”, then the process of fixing errors and improving the layout for maximum ease of both playing and reading is extremely easy. Hopefully, those old “hieroglyphic” editions will gradually be replaced by modern “user-friendly” editions.