Baroque and Pre-Baroque Period: Style and Interpretation

On this page we will be talking about style and interpretation in the playing of music from the Baroque (1600-1750) and Renaissance (1400-1600) periods (all these dates are of course quite approximate). For a discussion of the history and repertoire of these periods, click on the highlighted link below.

Baroque and Pre-Baroque Cello Music: History and Repertoire

There are many similarities in style and interpretation between the Baroque and Classical periods so there is considerable overlap between this article and the page dedicated to Style and Interpretation in the Classical Period.

AUTHENTICITY

The older the music, the further away it is from our times and therefore the greater the effort required to understand its historical context. This is why it is Baroque and Pre-Baroque music that tends to suffer the most from “uninformed” performance practices (basically, from being played as though it were Romantic music).

Usually, we think of evolution as leading us on a path to improvement. “Newer” normally means “better”: the most recent model of anything is usually an improvement on the previous version. Who then – apart from eccentrics or very poor people – would drive an old car, use a typewriter, an old camera, bicycle, gut strings, a Baroque bow, a light sound, little vibrato etc when there are such fantastic improved modern versions available? This reasoning was applied not just to performance style but also to whole musical epochs: Early Music (pre-romantic) was for a long time considered “old-fashioned”: simple and inferior to Romantic music. The Romantic Period was a time in which instrument manufacturing, emotivity, symphonic composition and virtuosic playing technique all flowered. This was such an amazing period in musical history that it is very easy for us to get stuck in a time warp, playing everything as though seen through this gorgeous romantic technicolour lens.

Because cello technique has improved over time, “Early Music” – being often somewhat less virtuosic than more recent music – can be considered as just “too easy” “not challenging” and therefore “boring” for the virtuoso instrumentalist. For all these reasons, the argument most commonly used to denigrate the “authentic performance, original instrument” revolution in Early Music musical interpretation, was (and is) that it was only for eccentrics and poor (incompetent) instrumentalists. Early music enthusiasts were considered as the musical equivalent of the Amish. Nowadays, fortunately, the tables have turned, and playing “Early Music” in the style of Russian romantic music has become not just “old fashioned” but even an almost embarrassing sign of a lack of awareness, musical education, intelligence and open-mindedness in the performer.

To play Early Music really “well” (to greatest effect) in its “authentic” style, requires much greater use of the intellectual components of interpretation than is required for playing Romantic Music. Choices of tempi, articulations, bowings, phrasings, dynamics, rhetoric, rubato etc are important in all musical styles but they are absolutely primordial in Early Music because the fundamental tools of Romantic Interpretation (instrumental virtuosity, big juicy sound and intense romantic emotional outpouring) are either unnecessary or inappropriate. Because that gorgeous luscious sound that we take as our romantic ideal would have been impossible to achieve with a baroque cello, baroque bow and gut strings, we have to find other ways to make this music powerful, moving, dramatic, beautiful etc.

This is probably why the “authentic”, “original instruments” world of pre-Romantic interpretation has always attracted so many of the most thoughtful, intellectual musicians. In the cello department Christopher Coin, Anner Bylsma, Claudio Ronco, Josetxu Obregon and others are not just fantastic cellists but seem also to be on a different intellectual and interpretative plane than your average “romantic” cellist for whom playing everything “beautifully” is often the ultimate goal.

Let’s look now at some of the defining characteristics of Baroque and Pre-Baroque music and cello playing:

THE CELLO ? ……..

Before the early 1700s the word “cello” could refer to many quite differently sized (and tuned) instruments. Not only was the cello a very new and non-standardised invention at this time but also it had a very popular predecessor – the viola da gamba – which it gradually came to replace. This means that a great amount of Baroque (and all Renaissance) music that we now play on the cello was, in fact, not originally written for the cello as we know it. Telemann (1681-1767), for example, wrote the vast majority of his cello-register music for the gamba, and even the Bach Cello Suites seem to have been intended for a smaller instrument on which violin fingerings were used (see Bach: Cello Size and Violin Fingerings).

For a chaotic list of quotes and references to articles about the cello’s history, click on the following link:

Cello History: Quotes and References

THE BAROQUE SPIKE AND CELLO ANGLE

The spike/endpin was only invented in the 1830’s, at the start of the Romantic period. All Baroque and Classical Period music was therefore originally played without a spike/endpin, which has major repercussions on playing style, posture and interpretation. Automatically, the cello angle is more vertical, the bow’s pressure on the string is naturally lighter, and we are obliged to sit forwards on our chair. Simply playing without a spike is a very revelatory experiment that can teach us as much about pre-romantic style and interpretation as reading the many books and treatises that are available on the subject.

ORNAMENTATION

Ornamentation is a vital expressive component of most Baroque music (as well as of baroque architecture, decoration, art etc), reaching its absolute peak towards the end of the Baroque period (see Rococo Style). As a general rule, trills should be started on the beat (not with a grace note before the beat), and from the note above. We can usually take our time over this first note of the trill, thus making the most of its highly expressive dissonance.

THE LEFT HAND

In “Early Music”, we generally use less vibrato, stay more in the lower positions, and use fingerings across the strings rather than shifting up and down the same string. Whereas in Romantic music we tend to avoid playing longer notes on the open strings (because we can’t do vibrato on them), the opposite is true in the Baroque (and Classical) style. Open strings with their beautiful natural (unforced, effortless) resonance and overtones are just wonderful in Pre-Romantic music.

FINGERINGS: KEYBOARD OR ROMANTIC ?

“Authentic Baroque” fingerings tend to use the lowest possible positions on the fingerboard, with the corresponding frequent use of both the open strings and string crossings (changes of string). These fingerings could be called “keyboard” fingerings in the sense that, by favouring string crossings over shifts, they avoid vocal glissandi. “Romantic” fingerings, on the other hand, will often follow a lyrical slurred melodic line, up and down the same string, giving the passage a more lyrical, vocal quality.

SHIFTING AND GLISSANDI

The prominent expressive glissando is very much a romantic-and-afterwards phenomenon. Much of the music of the Classical and Baroque epochs (and before) was written for palaces and churches. Religious and royal decorum have never been renowned for their public shows of emotivity and sensuality and, in music of these styles, this expressive device is often inappropriate and will need to be avoided. Before the Baroque period, most of the stringed instruments including the Lira (Viola) da Gamba and Lira da Braccio (precursors of the cello and violin family) had frets, so even if they had all wanted to, the only musicians who could really join the notes together with glissandi were singers and sackbut players (the sackbut was a precursor of the trombone). For this reason, in music of these early epochs, we will probably use expressive glissandi only in passages that use a melodic, singing style (usually slow movements).

For shifts that occur during a slur, we can relax the bow pressure and speed in order to make the glissando less audible. For shifts that occur on a legato bowchange we can achieve this same “camouflage” effect by doing our shifts on the “old” bow rather than on the “new” bow.

Even though audible sliding (glissandi) effects are used much more in Romantic music, pre-romantic glissandi can be absolute magic. Upward shifts on a bowchange can be made hugely expressive – but in a very discreet way – if we shift on the old bow and on the new finger. This is a perfect technique for “Classical Period” music, for which the Romantic swooping glissando on the new bow is just too much (see also Shifting And The Bow). Christophe Coin is an absolute master of this type of shift.

This is such a beautiful and powerful expressive device that we may often want to use it even when a shift is not absolutely necessary, as in the second shift of the above example.

The subjects of glissandos (and on which bowstroke to do them) are dealt with in more detail on their own dedicated pages in the shifting department:

The Glissando Shifting and the Bow

THE RIGHT HAND

The Baroque bow is a very different tool to the “Classical” and ultimately “Tourte” bows into which it evolved during the Classical period from around 1785/1790. The Baroque bow has a more pronounced natural tendency to get softer towards both ends and louder towards the middle than the modern bow. Its attack (articulation) was much smoother and softer as the hair tension was lower. When we play Renaissance, Baroque and early Classical Period music we need to be aware of these differences.

Even if we are using a modern “romantic” bow, we can imitate the early bow by using lighter, faster bow strokes and by playing less legato and less sostenuto in general. Romantic sostenuto legato bowing doesn’t have much place in stylistic (authentic) Baroque playing. Therefore, to play in a more “authentic”, less romanticised style, it can help to let the longer bow strokes fade out a little towards their ends, as in the following examples taken from the Bach Solo Cello Suites:

Exactly the same principle applies to Classical Period music. While the starting notes of the two Haydn Cello Concertos need to fade out a little if played in “authentic” style, the starting notes of the Dvorak and Schumann Concertos definitely do not want to do this.

In the above examples, each “long” bow is only one note. We can, however, use exactly the same technique of fade-out also when the bowstroke involves more notes, as in the following examples:

Baroque bowing doesn’t only use a lot of fade-outs, it also uses a lot of fade-ins, especially for very long notes. Some good examples of this can be found in Bach’s “Air On The G-String” and the first movement of his First Sonata for Violin and Harpsichord. Here, the bowed instrument is imitating the singer’s voice, with the imperceptible start from “niente” followed by a crescendo which can either fall back away (diminuendo) or continue on (crescendo) towards the next note. In fact, on very long notes, it can do all of these: growing, then fading and then growing again !

We do need to be careful however with these effects as, if overdone, they can make people seasick. Our vibrato width (but not speed ?) can also mimic this bowing effect, increasing towards the middle of the note and then diminishing towards the end of it, but, once again, this is a very subtle and delicate effect and if we overdo it our interpretation can become ugly and over-romanticised.

Nowadays any string player can buy a reasonable imitation Baroque bow for less than 200€. This is a very good investment and is well worth the cost. Playing with a baroque bow can actually teach us more about Baroque and Classical styles than many books or lessons. But even without buying a baroque bow we can simulate the effect of having one simply by holding our bow further away from the frog, closer to the bow’s centre of gravity. This simple displacement of the hand greatly reduces its leverage effect, and thus instantaneously makes the bow feel much lighter. Now our bow really is like a brush, rather than an axe or a hammer !

BAROQUE RIGHT-HAND ARTICULATION:

1: “MIND THE GAPS” AND “SHORTEN THE SLURS”

There are many unwritten rules (customs) concerning how to play Pre-Romantic music in an authentic, appropriate style. One of these “rules” is that when we encounter short slurs (especially 2 and 3-note slurs) in Baroque (and Classical period) music we almost always need to shorten the last note of the slur. Another of these “rules” is that the longer notes often should not be sustained for their full notated duration and should in fact be separated from the following note. This separation, rather than being a “silence”, is in fact full of the resonance of the previous note. Minuet I of Bach’s 2nd Cello Suite gives us many excellent examples of both of these stylistic customs.

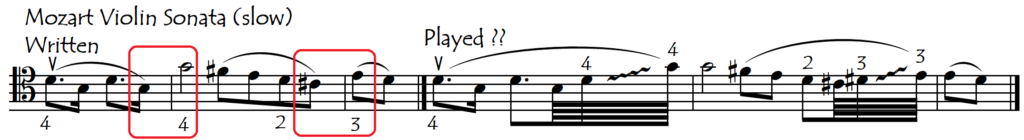

An exception to these “rules” occurs however in music which has a singing, lyrical, vocal style. Here, the only gaps are where the “singer” needs to breathe. Even though the following example is from the Classical Period, exactly the same principle applies to Baroque music:

2: PLAY 16TH NOTES LONG AND 8TH NOTES SHORT

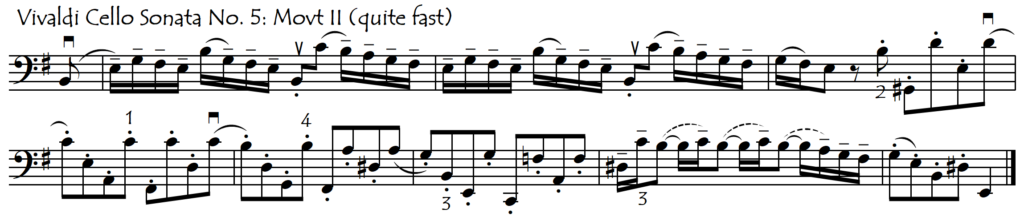

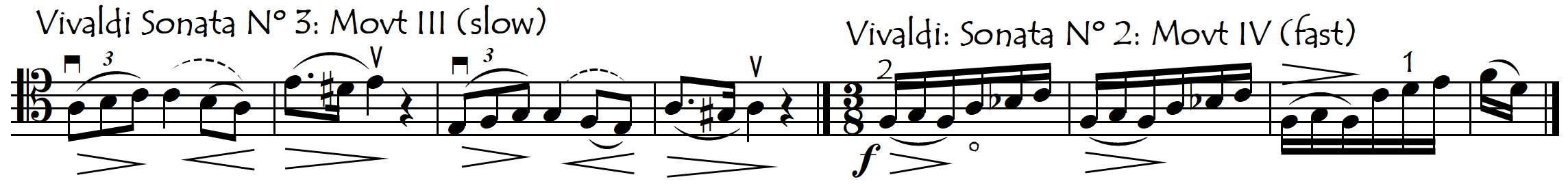

Another unwritten rule is that for non-slurred notes (especially in Baroque music from Italy), we can often apply the general principle of “play the 16th notes long and the 8th notes short”. The ideal place in the bow for the 16th notes (long) is in the middle or upper half while the short 8th notes will often want to be in the lower half. The Vivaldi cello sonatas and concertos provide us with numerous examples in which we can use this type of articulation: