Gamba, 5-String Cello and Arpeggione Music on the Cello

The “Violoncello Piccolo”, an instrument for which Bach wrote quite considerably (Sixth Solo Cello Suite and at least twenty Cantatas) has five strings: the four normal cello strings plus a higher E string. The “Arpeggione”, instrument for which Schubert wrote his extraordinary Arpeggione Sonata, is very different. While it has the same additional high E string, it then has five other (lower) strings which are tuned to guitar tuning, with the following open-string pitches (from bottom to top): E, A, D, G, B, and E. The Viola da Gamba has between 5 and 7 strings and is tuned, like the Arpeggione, mainly in fourths. None of these instruments has an extra string tuned lower than the cello’s C string, but all have at least one additional string above the cello’s A string.

Because of the cello’s lack of the higher E string, playing the repertoire of these instruments on a normal 4-string cello is almost identical to playing virtuoso violin pieces in their original key, with the only difference being that here, unlike for violin pieces, we will need our lowest (C) string. Using a normal 4-string cello for this repertoire is like asking a tuba to play a trumpet part: we are completely out of our normal cello register.

Fortunately for transcription purposes, the C string is used very little in most of the repertoire for these instruments. For example, it is used for a total of only 6 notes in Bach’s three Gamba Sonatas, 17 in the Arpeggione Sonata, and somewhat more (46 to be precise) in Bach’s Sixth Suite. Therefore, with a few minor modifications (to substitute for those low notes), we can apply the same principle to these pieces as we do to other violin pieces, and thus choose to transpose them down a fifth in order to bring them into a more comfortable cellistic register (click on the links to the actual pieces for a more detailed description of these adaptations).

If we have the good luck to have the use of a 5-string cello, we can play this music at its original pitch, but we may still find it easier to play from a part that is written out a fifth lower and just play as if our top (E) string was simply an A string. Although the music will sound a fifth higher than it is written, this way of writing/reading makes life easier for us in two ways:

- it eliminates most of the reading problems as these high pieces usually make much greater use of the new high string than they do of the C string. It is easier to learn to read a few notes below the C string than hundreds of notes on the E string.

- we eliminate the problem of knowing on which string we are playing (for both the bow and the left hand). This is because our positional sense for both hands is extremely relative: any one string serves as the positional reference from which we find the other strings. When what has always been our top (“A”) string suddenly becomes the second (“D”) string – and likewise for all the other strings – we can rapidly get completely lost with both hands. If, by contrast, we just pretend that the top string is always the A string, we avoid this problem entirely. This is exactly the same principle that we use in “scordatura”. In “scordatura” we write the note that corresponds to the finger we want to use rather than to the pitch it will actually sound (Bach Suite V, Kodaly Solo Sonata). We do this in order not to confuse our brain and its deeply programmed pitch-finger-string correspondences. If we write out music for a 5-string cello a fifth lower than it actually sounds, we are following exactly the same principle, but instead of deluding the brain only about the pitch our finger is playing, we are now deluding it about both the pitch and which string our bow is on. It’s a little like a “white lie” – it may seem like “cheating”, but it certainly saves our brain an awful lot of work.

This is why the pieces, conceived for a 5-string instrument, that are offered on this website in versions for both 4-string and 5-string cellos, are always written out a fifth lower. In fact, the only difference between the sheet music of the two versions is that the 5-string version has all the lower notes (written out below the C string), that had to be substituted (rearranged) for the 4-string versions because they were out of range (too low).

For musicians with perfect pitch, however, this solution may actually create more problems than it solves because now every note we play sounds at a different pitch to how it is notated. In normal scordatura writing, only the notes on the retuned string(s) sound at a different pitch to how they are notated.

THE GRAY AREA: FIVE STRINGS OR FOUR?

Some pieces of the Baroque and Early Classical Periods, which are presented as “cello” compositions, may actually have been composed for a 5-string cello. At that period, the cello was not yet a standardised instrument, and the word “cello” could refer to instruments of different sizes and with either 4 or 5 strings, such as the Viola da Spalla, Viola Pomposa, Violoncello Piccolo and even perhaps the Viola da Gamba (see Cello History).

Some of Vivaldi’s high-register cello concertos (RV 413, 418 and 424, among others) are impossible to play on a 4-string instrument without the use of the thumbposition. Considering that in Vivaldi’s time (1678-1741) thumbposition was not yet “discovered”, we can only assume that they were written for a 5-string instrument even though he didn’t specifically mention this.

It is possible that Haydn also intended some of his higher register cello compositions (D major Cello Concerto, Sinfonia Concertante etc) to be played on a 5-string instrument. The writing in these pieces is so much higher than his normal cello writing (including that of his C major cello concerto) that we can justifiably wonder if perhaps the cellist for whom Haydn wrote these two pieces had a high E-string on their instrument. Click on the highlighted links (above) to see all of the thumbposition passages of these two pieces written out down a fifth. This is how they would be (where they would lie on the fingerboard) if we played them on a 5-string cello. Suddenly these pieces become infinitely easier. Now we no longer need to be Paganinis-of-the-cello to play this piece well.

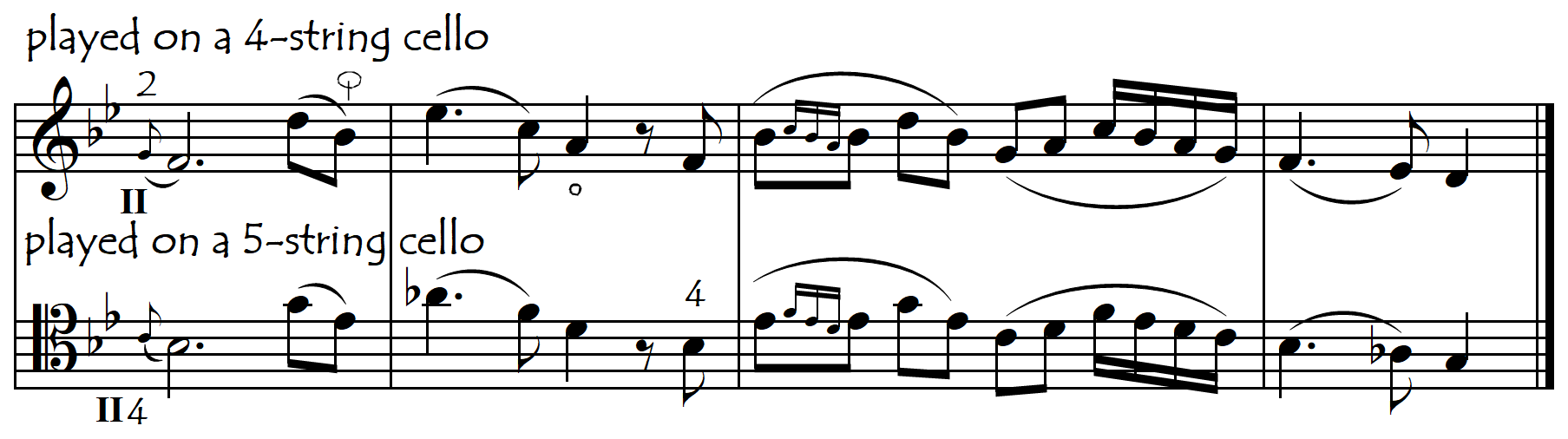

Compare for example the difficulty of the cellist’s first melodic solo intervention in the Sinfonia Concertante in the two following versions (for 4-string and 5-string cello). Of course, the 5-string version will sound a fifth higher (i.e. the same pitch as the 4-string version) if played on a 5-string cello:

PLAYING MUSIC THAT WAS CONCEIVED FOR A NORMAL CELLO, ON A FIVE-STRING INSTRUMENT

Above, we have looked into the problems of playing 5-string music on a 4-string cello. Now, let’s talk about the exact opposite: the advantages of playing some “normal” (but high) cello music on a 5-string instrument. Having that fifth (high) string can make some very difficult high passages suddenly become very easy, even in music that would seem to have been written for a normal 4-string cello. In Boccherini’s many Cello Sonatas the C string is so rarely used so we could quite easily transpose them down a fifth, but he so obviously loved the cello’s higher (and highest) registers that this downward transposition would change the essential character of the music. A more practical solution would be to play this music on a 5-string cello, thus suddenly making it infinitely more pleasant, both for the listener and the player.

And for jazz and pop, the benefits are even clearer. This music is almost always amplified so the acoustical and ergonomic complexities of a traditionally-made 5-string cello are irrelevant: we can simply use a solid 5-string electrical instrument. Even the Yamaha Silent Cello (a wonderful sounding 4-string electrical instrument) can easily have a fifth string added to it.