Baroque and Pre-Baroque Period: History and Repertoire

While the Baroque Period in music is generally considered to cover approximately the period from 1600-1750, the cello – an Italian invention – did not appear till the end of the 1600s. Stradivari’s first cellos date from this time, as do the first compositions specifically written for cello: collections of Ricercares by Giovanni Antonii (1687) and Domenico Gabrielli (1689), as well as Domenico Galli’s “Trattenimento Musicale Sopra Il Violoncello Solo” (1692).

While the Baroque Period in music is generally considered to cover approximately the period from 1600-1750, the cello – an Italian invention – did not appear till the end of the 1600s. Stradivari’s first cellos date from this time, as do the first compositions specifically written for cello: collections of Ricercares by Giovanni Antonii (1687) and Domenico Gabrielli (1689), as well as Domenico Galli’s “Trattenimento Musicale Sopra Il Violoncello Solo” (1692).

That the cello was still not a standardised instrument is shown by the fact that Antonii’s work is written for a cello with six strings, tuned like the contemporary viol (mainly in fourths) except for a scordatura of the lowest string (depending on the key) while Galli’s is written for a 4-string cello, but also tuned in fourths.

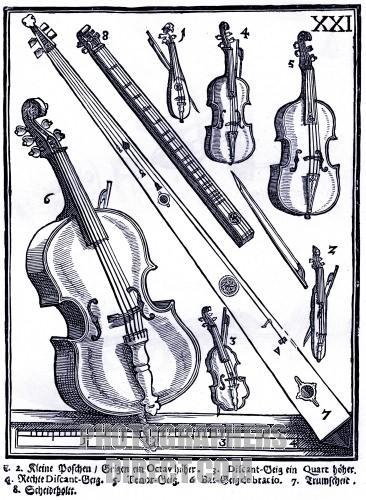

The first orchestral compositions specifying the use of the “cello” appeared around 1700: to be precise, in Gasparini’s Cantata Op.1 (1695) and Scarlatti’s cantatas (1690s), written in Rome and Naples. Before this time the cello basically did not exist as such, and all the music that was written for bass-register string instruments was played on its various predecessors: the violone (ancient doublebass), the viola da gamba, viola da spalla, viola pomposa, bass violin (see picture on right) etc. In fact, it is even possible that the Bach Cello Suites were written to be played on one of these smaller instruments (see the following article). To avoid confusion, we need to remember that “Viola de Gamba” is the Italian term that translates to “Basse Viole” in French. Likewise “Doublebass” – the bass-register instrument of the violin family – translates to “Violone” in Italian.

That the cello as we know it originated in Italy is confirmed by the French musician Michel Corrette who, in his Traité de Violoncelle (1741) – probably the first-ever “cello method” – attributed to the influence of Italian players and composers the introduction of the violoncello to Paris, in the early eighteenth century. This introduction of the cello met with a huge success in France. By the late 1730’s the enthusiasm for the cello there was such that between 1738 and 1750 26 volumes of cello sonatas were published (by Le Clerc). This success gave rise in 1740 to a famous article “Defense de la Basse Viole Contre Les Entreprises du Violon et les Pretensions du Violoncelle” (Le Blanc) (“In Defense of the Basse Viole [Viola da Gamba] Against the Encroachments of the Violin and the Pretensions of the Cello”).

From the very beginning of the cello’s history, we can see a progressive “emancipation” from its initial role as a humble bass instrument (simply doubling the Basso Continuo) towards a more melodic, soloistic instrument whose register was progressively extended upwards into the tenor register and beyond. Already in Scarlatti’s cantatas of the early 1700’s the first steps of this emancipation can be seen in the fact that the bass line was now divided into two staves: one for the Basso Continuo, and the other – with both a higher register and a more elaborate part – for the cello. This emancipation continued throughout the 18th century with the cello becoming, in the second half of the century, a fully-fledged solo instrument – while at the same time preserving its ability to simply double the bass line.

USE OF THE HIGHER FINGERBOARD REGIONS

USE OF THE HIGHER FINGERBOARD REGIONS

In the Renaissance and Early-Baroque periods, neither thumbposition nor the higher registers were ever used (note the extreme shortness of the fingerboard in most pictures of cellos in this epoch). The cellist’s left hand was confined to the Neck Region, almost never going higher than the half-string harmonic (“A” on the “A” string). The sonatas of Vivaldi, Marcello, De Fesch, Geminiani, Galliard etc illustrate this characteristic perfectly (with the exception of one bar in Vivaldi’s 8th Sonata in which the cello goes up to Bb on the “A” string).

The high register cello writing that we find in “cello” music of this time was intended either for non-standard-tuning cellos (such as the 5-string “violoncello piccolo” used in approximately twenty Bach Cantatas and his Sixth Cello Suite, as well as in several of Vivaldi’s Cello Concertos) or for instruments of the Viola da Gamba family (Bach’s Gamba Sonatas and all compositions by Ortiz, Marais, Couperin, Rameau etc.). Most other “Baroque” pieces that require the use of the higher registers (Intermediate and/or Thumb Regions) are simply transcriptions or arrangements for the cello of Baroque violin music in which the original “violin key” has been retained. A huge amount of these arrangements exist, almost all of which were edited and published in the 19th and 20th centuries (sonatas by Eccles, Valentini, Locatelli, Veracini ….. concertos by Tartini. etc).

The thumb – and the higher registers in general – only began to be used extensively in the transition period between Late Baroque and Early Classical but it was the cellist-composers of this period, rather than the grandmasters, who were initially responsible for this evolutionary leap. Neither Bach nor Vivaldi ever used thumbposition. In fact, neither even used the Intermediate Region on more than a handful of occasions. Their excursions up beyond the half-string harmonic on the top string (including in their works for the 5-string Violoncello Piccolo) can literally be counted on one hand: Bach did it only once (in the Prelude of the Sixth Suite) and Vivaldi did it once in each of his 8th Cello Sonata, Double Cello Concerto and Cello Concertos RV 401, 418 and 424. Apart from these brief daring incursions into the tenor register, the cellists left-hand stays permanently in the Neck Region.

In contrast to this “conservatism” of Bach and Vivaldi, it appears to have been some of the adventurous Italian cellist-composers who broke through the fingerboard frontier, making the quantum leap into thumbposition and the highest cello registers. Salvatore Lanzetti (1710-1780), used thumbposition and the high registers frequently in Nos. 5, 8, 9,11 and 12 of his 12 Cello Sonatas Op.1 (published around 1736) in which the cello’s range is extended up to the A, two octaves above the open string and even (once) up to the B, one tone higher. Antonio Vandini, in his sonata in C Major – of which a manuscript copy seems to be dated 1717 – also takes the left hand into thumb position, regularly going up to “C”, a third higher than the half-string harmonic. In his F major and G Major Sonatas he goes even higher, with extended (but simple) passagework with the thumb on “C” on the A string (highest note “F”). The drawing on the right shows Vandini, playing high in the Thumb Region, but holding his bow “underhand” in Gamba style! Thumbposition caught on rapidly in France. In Michel Corrette’s treatise of 1741 (see above) thumbposition is clearly explained, and the 5 Sonatas Opus 1 of Bert(e)au (1748) are full of carefully fingered thumbposition passages.

In contrast to this “conservatism” of Bach and Vivaldi, it appears to have been some of the adventurous Italian cellist-composers who broke through the fingerboard frontier, making the quantum leap into thumbposition and the highest cello registers. Salvatore Lanzetti (1710-1780), used thumbposition and the high registers frequently in Nos. 5, 8, 9,11 and 12 of his 12 Cello Sonatas Op.1 (published around 1736) in which the cello’s range is extended up to the A, two octaves above the open string and even (once) up to the B, one tone higher. Antonio Vandini, in his sonata in C Major – of which a manuscript copy seems to be dated 1717 – also takes the left hand into thumb position, regularly going up to “C”, a third higher than the half-string harmonic. In his F major and G Major Sonatas he goes even higher, with extended (but simple) passagework with the thumb on “C” on the A string (highest note “F”). The drawing on the right shows Vandini, playing high in the Thumb Region, but holding his bow “underhand” in Gamba style! Thumbposition caught on rapidly in France. In Michel Corrette’s treatise of 1741 (see above) thumbposition is clearly explained, and the 5 Sonatas Opus 1 of Bert(e)au (1748) are full of carefully fingered thumbposition passages.

CELLO SIZE, STRING LENGTH AND FINGERINGS IN THE BAROQUE PERIOD

Up until at least the mid 18th century, it would appear that the fingerings used on the cello were basically the same as violin fingerings (with the use of one tone extensions between each finger – see picture on the right of Salvatore Lanzetti). This is no doubt why Quantz wrote in 1752: “Solo playing on the cello is not easy. Those who wish to distinguish themselves in this manner must be provided by nature with fingers that are long and have strong tendons, permitting an extended stretch”. Curiously, both Leopold Mozart and Quantz, in their respective treatises on music written around the mid-1700s, describe two different cello sizes: a smaller cello for solo playing and a larger one for orchestral playing. It is only in 1740 that Michel Corrette’s Treatise (mentioned above) proposes the revolutionary new idea of using a semitone between each finger as the standard fingering.

The occasional use of the thumb in the Neck Region that is required on the modern cello to play certain passages in the Third and Fourth Bach Solo Cello Suites reinforces the theory that the Bach Suites were written to be played on a much smaller instrument than the modern cello: probably the Viola Pomposa or the Viola da Spalla, both of which are played with violin fingerings. This smaller size would have allowed these passages to be played simply with stretches between the fingers rather than with the use of the thumbposition which is unavoidable with the modern cello’s size.

The occasional use of the thumb in the Neck Region that is required on the modern cello to play certain passages in the Third and Fourth Bach Solo Cello Suites reinforces the theory that the Bach Suites were written to be played on a much smaller instrument than the modern cello: probably the Viola Pomposa or the Viola da Spalla, both of which are played with violin fingerings. This smaller size would have allowed these passages to be played simply with stretches between the fingers rather than with the use of the thumbposition which is unavoidable with the modern cello’s size.

THE CELLO BOW AND BOWHOLD

The cello bow and bowhold are vastly different now from how they were in the Baroque times. For discussion about this see the article Baroque Interpretation

CELLO, VIOLA DA GAMBA (BASS VIOL) OR VIOLONE (BASS)?

Because the cello did not exist as such until the 1690s, the composers who preceded its introduction wrote either for the Viola da Gamba (Ortiz, Colombe, Marais, Schenck) or for the Bass (Purcell, Corelli). The Bass (violone) was not a melodic instrument and was limited to playing the Basso Continuo parts. Both the cello and gamba however could be used as obbligato (melody) instruments so, after the cello’s establishment, it became possible for composers (and players) to choose between these two instruments.

Because the cello did not exist as such until the 1690s, the composers who preceded its introduction wrote either for the Viola da Gamba (Ortiz, Colombe, Marais, Schenck) or for the Bass (Purcell, Corelli). The Bass (violone) was not a melodic instrument and was limited to playing the Basso Continuo parts. Both the cello and gamba however could be used as obbligato (melody) instruments so, after the cello’s establishment, it became possible for composers (and players) to choose between these two instruments.

While Couperin and Rameau stayed exclusively with the gamba, most others (especially the cellist-composers) converted completely to the cello. Telemann and Bach however continued writing for both instruments. Telemann’s Paris Quartets of the 1730s were written for flute, violin, basso continuo and cello-or-gamba. So that the gambist and cellist could take turns playing the obbligato (melodic) and continuo bass lines, Telemann composed separate (but identical) versions of the obbligato part, one for viola da gamba and the other for cello. The only difference in the parts is the clefs that he uses: tenor and bass clefs for the cello part and “viola” and bass clefs for the gamba part.

********************************************************************

THE END OF THE BAROQUE PERIOD

The deaths of Vivaldi in 1741, J.S. Bach in 1750 and Handel in 1759 can be considered perhaps as signifying the progressive “beginning of the end” for the Baroque period. By the middle of the eighteenth century, a new musical style was appearing that is known as “Rococo” or “Preclassical” style. In the world of painting the Rococo style is characterized by delicate colours, many decorative details, and a graceful and intimate mood. Similarly, music in the Rococo style is monophonic (in contrast to polyphonic/contrapuntal), light in texture, melodic, and elaborately ornamented. In France, the term for this was “style galant” (gallant or elegant style) and in Germany empfindsamer Stil (sensitive style). Towards the end of the eighteenth century, a reaction against the Rococo style occurred. There were objections to its lack of depth and to the use of decoration and ornamentation for their own sake. This led to the development of the Classical Style (approximately 1775-1825).

REPERTOIRE AND TIMELINE

Let’s look now at a timeline for the Baroque period. Here we can see not only the grand masters but also cellist-composers (indicated with a “*” sign), lesser-known composers who wrote for the cello (and/or its predecessors) as well as some literary and historical figures. Click on the highlighted composers to see which pieces of theirs are available for download.

Colombe 1640 ………………… 1700

Gabrielli 1651 …1690

Pachelbel 1653 ……………. 1706

Corelli 1653 …………………. 1713

Marais 1656 ……………………….. 1728

Purcell 1659 .. 1695

Schenck 1660 …………….. 1712

A. Scarlatti 1660 ………………….. 1725

Couperin 1668 ……………………… 1733

Caldara* 1670 …………………….. 1736

Eccles 1670 ………………………… 1742

G: Bononcini* 1670 ………………………….. 1747

Vivaldi 1678 ……………………..1741

Valentini 1681 ………………………… 1753

Telemann 1681 ………………………………. 1767

Cervetto* 1682………………………………………………. 1783

Marcello 1683………………….. 1739

Rameau 1683 ………………………………… 1764

J.S. Bach 1685 …………………….. 1750

D. Scarlatti 1685 ………………………….. 1757

Handel 1685 ……………………………. 1759

Porpora 1686 ………………………………… 1768

Senaillé 1687 ……………….1730

Galliard 1687 …………………….. 1747

De Fesch 1687 …………………………….. 1761

Geminiani 1687 …………………………….. 1762

Veracini 1690 ……………………………….. 1768

Vandini* 1690 ……………………………………….. 1778

Tartini 1692 ……………………………………. 1770

Leo 1694 ………………… 1744

Locatelli 1695 …………………………….. 1764

Berteau* 1708 ……………………………… 1771

Pergolesi 1710 …….. 1736

Guerini 1710 …………………………. 1770

Lanzetti* 1710 …………………………………. 1780

CPE Bach 1714 ………………………………………. 1788

If we look now at these same composers in a timeline according to their death dates, we get a different – and perhaps more realistic – idea of where their mature output lies in the Baroque timeline. Here, for example, we can see how Bertau and Lanzetti, the cellist/composers who initiated the use of thumbposition, are found at the end of the Baroque timeline, because both had extremely long lives (for their epoch). Both died approximately 30 years after J.S Bach, who never discovered the possibilities of using the thumb on the cello fingerboard.

Gabrielli 1651 …1690

Purcell 1659 .. 1695

Colombe 1640 ………………… 1700

Pachelbel 1653 ……………. 1706

Schenck 1660 …………….. 1712

Corelli 1653 …………………. 1713

A. Scarlatti 1660 ………………….. 1725

Marais 1656 ……………………….. 1728

Senaillé 1687 …………….1730

Couperin 1668 ……………………… 1733

Caldara* 1670 ……………………… 1736

Pergolesi 1710 ………. 1736

Marcello 1683………………….. 1739

Vivaldi 1678 ……………………….1741

Eccles 1670 ………………………….. 1742

Leo 1694 …………………. 1744

G Bononcini* 1670 ……………………………… 1747

Galliard 1687 ……………………….. 1747

J.S. Bach 1685 ……………………….. 1750

Valentini 1681 ……………………………. 1753

D. Scarlatti 1685 ………………………….. 1757

Handel 1685 ……………………………. 1759

De Fesch 1687 …………………………….. 1761

Geminiani 1687 …………………………….. 1762

Rameau 1683 ………………………………… 1764

Locatelli 1695 ………………………….. 1764

Telemann 1681 …………………………………. 1767

Veracini 1690 ……………………………… 1768

Porpora 1686 ………………………………… 1768

Tartini 1692 ………………………………… 1770

Guerini 1710 …………………………. 1770

Berteau* 1708 ……………………………… 1771

Vandini* 1690 ……………………………………… 1778

Lanzetti* 1710 ……………………………….. 1780

Cervetto* 1682……………………………………………….. 1783

CPE Bach 1714 …………………………………….. 1788

REPERTOIRE NOTES

Cervetto: 12 solos for Cello and Basso Continuo (1750)

Galliard Six Solos for the Violoncello, and Six Sonatas for the Bassoon or Violoncello

Guerini 6 Sonatas for Cello Opus 9 (1765)

External articles (further reading):