Bach: Cello Suite Nº 6 BWV 1012: Discussion

The sheet music can be downloaded here in four versions:

- transposed down a fifth and adapted for a 4-string cello

- the same, but with the addition of a “walking bass” line for a second cello (or any other bass instrument)

- a comparison of the four existing manuscript copies

- written out down a fifth, but for playing on a 5-string cello (therefore no adaptations necessary)

The special peculiarity of this Bach Cello Suite is that it was, of course, written for a 5-string cello, with a high E string. The other, less significant peculiarity is that it is the most chordal of all the Suites, using more chords and doublestops (229) even than the 5th Suite which (with 205) was the former champion in this category (see the table showing the frequency of chord use in the Cello Suites in Bach: Chords and Doublestops). Let’s consider first the consequences of the use of the 5th string in this suite.

5 STRINGS OR 4?

If we play this suite on a cello with 5 strings, it lies (almost) in the same fingerboard region for the left hand as the other five suites and is of comparable difficulty. We say “almost in the same fingerboard region” because, even when played on a 5-string cello, the Prelude still takes us (in the progression from bars 72-77) right up to the top of the Intermediate Region (which corresponds, on the A string, to “C” above the octave harmonic). This is a fourth higher than Bach has ever taken the cellist’s hand in the previous five Solo Suites. In summary, even on a 5 string cello, this Prelude is still somewhat higher and more virtuosic than anything seen in any of the other Suites.

PLAYING IT ON A 5-STRING CELLO

Playing on a 5-string cello removes most of the unique technical difficulties that 4-string cellists face in playing this suite (see below), but it adds two new unique (but minor) “brain difficulties”.

- it is confusing for bow level control because the A-string is now the second string rather than the top string, the D-string now corresponds to the G-string etc

- it is difficult to read and find the notes that are played on the E-string because they are now played in the lower positions on that string instead of being played in the higher positions on the A-string.

These two difficulties normally mean that we require a period of adaptation to the 5-string instrument, but both difficulties can be eliminated if we write the music out a fifth lower and play our 5-string cello as though its top string were an A-string. This is what has been done in the editions offered here.

The greatest problem associated with playing this Suite on a 5-string cello is however that, unfortunately, almost none of these cellos exist. For more discussion about which instrument Bach wrote this Suite (and his other cello Suites) for, click here. Because of the unavailability of 5-string cellos, most cellists try to play this suite on a four-string cello. This creates several problems. Let’s look at these now:

DIFFICULTIES OF PLAYING IT ON A 4-STRING CELLO

1 EXTREME TECHNICAL DIFFICULTY

If we play this suite on a 4-string cello at the original pitch (i.e. as Bach wrote it), our left hand is often in the higher registers. In fact, it needs to go up to a high G on the A string, almost two octaves above the open string (Prelude, bar 74). This is one whole octave higher than any other piece that Bach ever wrote for the cello. Here, we are in Boccherini or Paganini territory – not Bach territory. What’s more, not only do we need to play “up high”, we also have to move up and down between the stratosphere and the depths of the C string with the same fluidity and ease that would be given by the presence of that missing fifth (higher) string. This is extremely difficult. It may be interesting as a technical challenge, but musically it is rather like a circus trick – and often a very dangerous one.

2. MISSING HIGH OPEN STRING = MISSING STRING-CROSSING SPECIAL EFFECTS

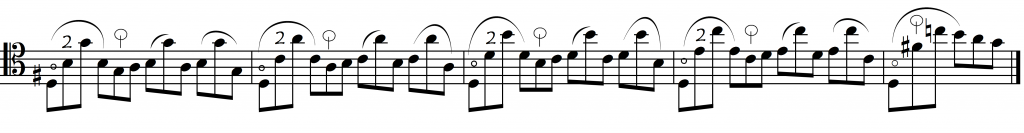

Bach knew perfectly well how to use the open strings to wonderful effect in certain string-crossing passages, most notably in the Prelude between bars 23 and 33. The following example shows how Bach imagined these bars, with this spectacular bariolage effect featuring upside-down string crossings and the higher open string. This is how the passage would be played on a 5-string cello, although it would of course sound one fifth higher:

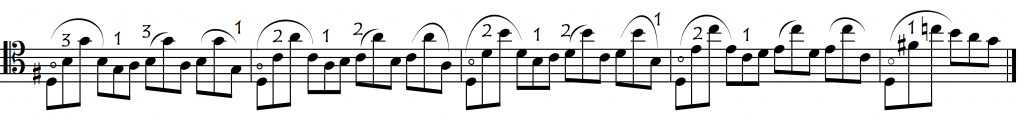

But when we play this Prelude at the original pitch on a 4-string cello, we don’t have that top open string that Bach imagined. Without the open string, not only do these wonderful special open-string effects disappear but also the passage becomes excruciatingly difficult, requiring some high-tech thumb gymnastics and very athletic hand contortions. In spite of our hard work and suffering, it can still easily sound not only out-of-tune but also nothing like it was originally supposed to.

3. CHORDS

Many chords become unplayable (or almost) when we play at the original pitch on the 4-string cello. This occurs most notably in the Sarabande, which is the most chordal of all of Bach’s cello suite movements.

CONCLUSION:

If we don’t have a 5-string cello, we can avoid all the above-indicated problems by playing this suite transposed down a 5th. This makes it immediately accessible to all cellists. It also enables all the special string-crossing effects that Bach uses so well. What the Suite “loses” in the transposition (through the modifications or suppression of the lowest notes and through the use of a lower register) is more than compensated for by these other technical and musical advantages. Why convert beautiful, wonderful, profound music into a virtuosic showcase (or an excruciating struggle) by playing it on the wrong instrument? On this website, we steal a lot of music from other instruments, but we always adapt it to the cello’s technical limitations and peculiarities so that it can sound great without the cellist having to be a superhuman virtuoso practicing 8 hours a day! Our transposition of this suite down a fifth follows this same logic.

Another advantage of playing this Suite transposed down a fifth is that, if we are lucky enough one day to have a 5 string cello in our hands, we can play from the same (almost) sheet music, in its version for a five-string cello (i.e. with all the lowest notes left in). By simply pretending that the top string (the E string) is an A string, the music now sounds “at original pitch” even though what we are reading is a fifth lower. This is possibly a much easier way to read and play music on a 5-string cello than reading the music written out at true pitch. As we mentioned above, reading “at true pitch” is very confusing both for bow level control (the A string is now the D string, the D string corresponds to the G string and so on) and for the left hand on the E string. This (reading at true pitch on a 5-stringer) requires considerably more brainwork. It is comparable to playing a scordatura piece written out at true pitch – and we don’t normally do that!!

Violists play this Suite transposed down a fifth ….. but is this the basis for another viola joke? NO! On the contrary, it is in fact further proof that viola players are often the most intelligent, least egotistical and most thoughtful of all string players (see also Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata).

PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH THE TRANSPOSITION DOWN A FIFTH

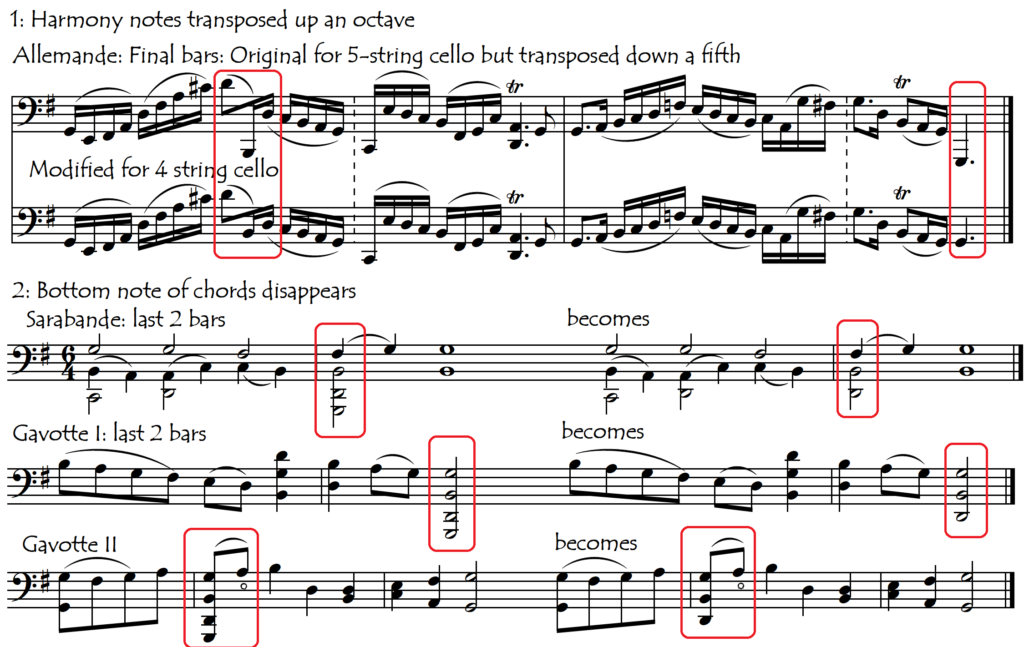

Of course, when we play it a fifth lower, some notes are out of register: they are too low to be played. In fact all of the notes in the 5-string version that lie on the C string have to be modified. Fortunately, this concerns only 46 of the 2963 notes (1.5%) that make up this Suite. When these unplayable notes are simply isolated “harmony notes” or the bottom notes of a chord, this is very simple to fix. In the case of an isolated harmony note, we can transpose the note up an octave. In the case of the bottom note of a chord, the note can be simply deleted. The uses of these two methods are shown in the following examples:

These necessary – but innocuous – modifications don’t cause any noticeable change to the musical line and, in the case of these four movements (Allemande, Sarabande and two Gavottes) no modifications other than those shown above are necessary.

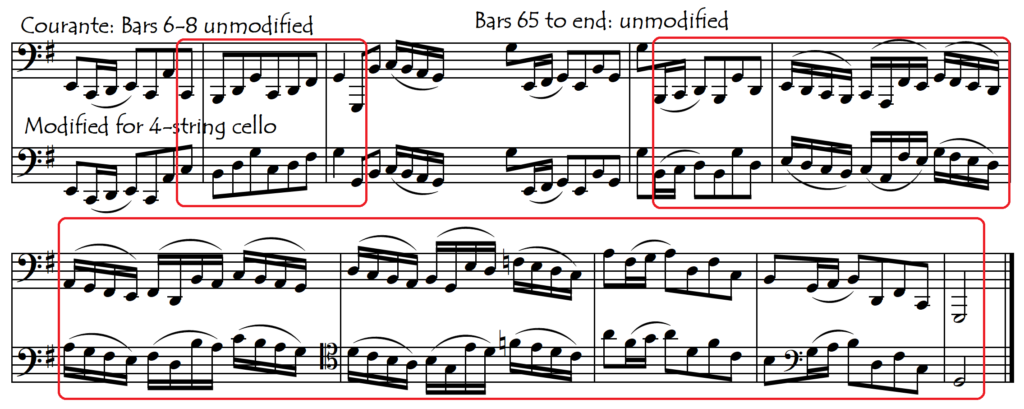

Sometimes however, one or several notes in a melodic passage go under our register. In these cases, it is preferable to conserve the original melodic line by transposing the entire passage up an octave as in the following examples taken from the Courante.

The Courante only requires the modification of 4 other notes, in bars 13, 14 and 31/32. These four harmony notes can all be simply transposed up an octave without disturbing the musical line.

We have dealt now with the Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, and Gavottes, in which a total of 17 notes (out of a total of 1960!) were out of range. All of these movements required only simple, minor changes (up an octave or suppression) to adapt them to the transposition down a fifth. The Prelude and the Gigue present slightly more problems. In these movements, there are some situations where we need to actually rewrite the music.

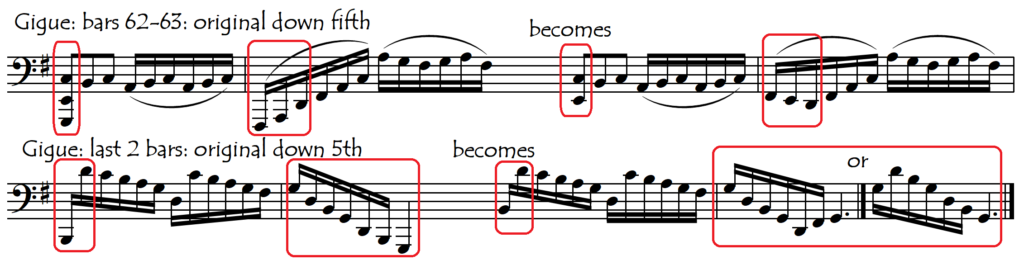

In the Gigue, 17 notes (from a total of 653) are out of range, in bars 16, 27, 45, 58/59, 60-63 and 67-68. Of these, all but bars 63 and 68 can be perfectly resolved using the innocuous techniques of octave transposition and suppression (in the case of the lowest note in the chord) as used in the examples above from the Allemande, Sarabande and Gavottes. Only bars 63 and 68 require rewriting which we have done in the following way:

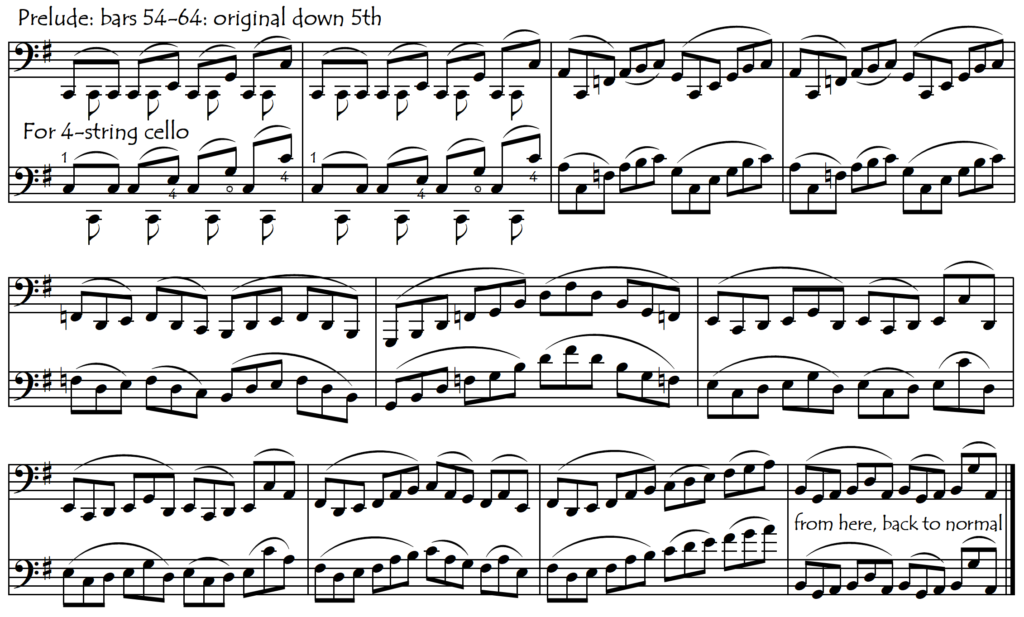

It is the Prelude that presents the most problems. Although only 12 notes (of the total of 1350) are out of range, in order to preserve the melodic line, and to avoid long passages in the lowest registers, ultimately 145 notes have been changed by an octave. This may sound like a lot of changes but, in fact, 136 of these notes belong to just two continuous phrases: bars 41-42 and bars 54-63 as shown in the examples below.

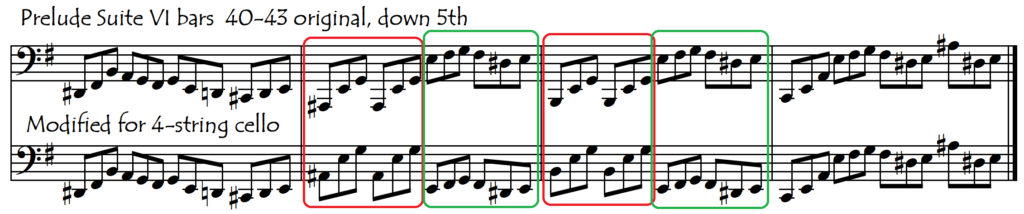

Sometimes, the octave transposition is slightly more complicated than simply changing every note of the phrase uniformly. In the first two bars of the above example, we have kept the low open C string in order to be able to have the string crossing effect that characterises this theme each time it appears. Also, in bars 41-42 (next example) we have transposed half of each bar up an octave (red enclosures) but the other half has been transposed down an octave (green enclosures) in order to maintain (but in reverse) the octave jumps of the original.

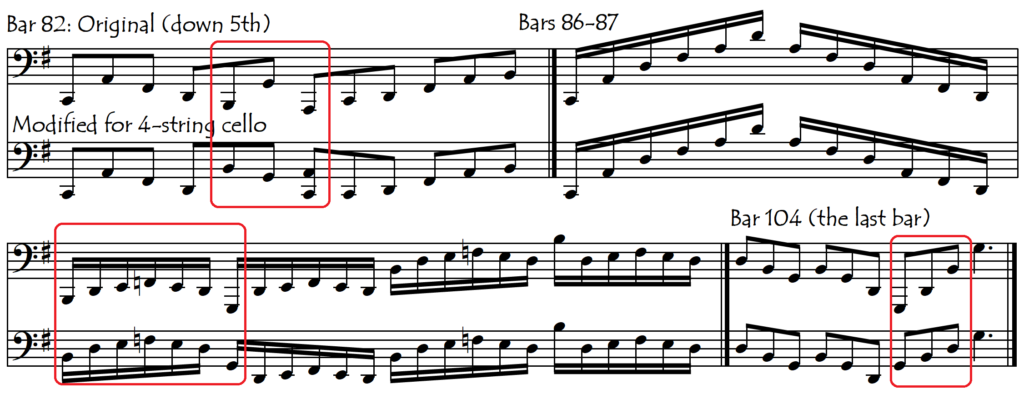

The only other changes in this movement are shown in the following examples:

ONE MORE EDITORIAL CHANGE: BACH AND THUMB POSITION

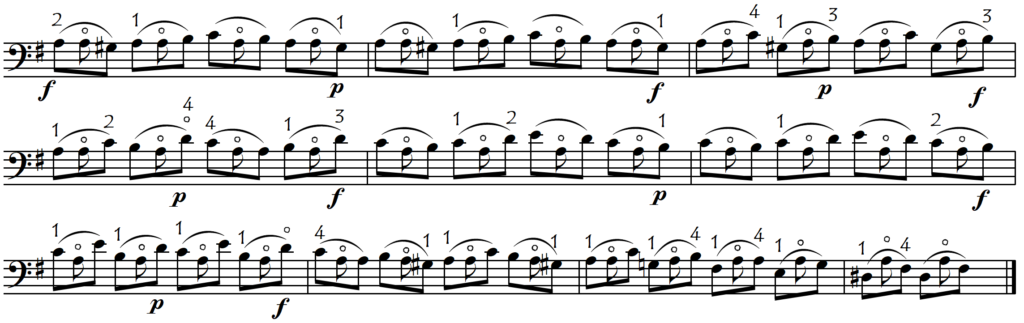

Even when this Suite is played on a 5-string cello (or transposed down a fifth on a 4-string cello) there are still some passages where the cello’s modern size requires the use of thumb position (see Thumb Position in the Bach Suites). If we are correct in believing that neither Bach nor his cellists were aware of the possibility of thumbposition, then this would seem to be further evidence for the fact that Bach wrote this suite (as well as the others) for a smaller instrument. In fact, one of these passages – bars 70 to 75 in the Prelude – would almost seem to prove the idea that Bach’s cellists never used the thumb. Play this passage on your normal 4-string cello with “standard” cello fingerings (using Thumb Position). This is how it would be played by a modern cellist using a 5-string cello (although of course, it would sound a fifth higher):

This is extraordinarily difficult because during the open D string we need to remove the left hand entirely from its contact with the cello. When we do this we lose all our positional and tactile references. To make things even worse, during this loss of contact, we have to do a shift. This is Absolute Positional Sense at its most absolute! Finding notes in this way is one of the hardest things we will ever have to do on the cello. If this same passage is played without using thumbposition, then our left hand maintains permanent contact with the cello via the thumb at its normal place behind the neck and we thus have none of these navigational problems.

This passage is like a vital clue to a musicological detective: it indicates simultaneously:

- that thumbposition was probably not used by Bach’s cellists

- that the cello for which Bach wrote the Suites was probably smaller than the modern cello, because the fingerings that are required to avoid the use of the thumb are basically impossible on the modern cello (with one tone stretches between each finger). In fact, Bach referred to his Viola Pomposa (a much smaller instrument than a cello and played in the violin/viola position) as his “Violoncello Piccolo”. See the following article for further discussion about what instrument Bach actually wrote his Suites for.

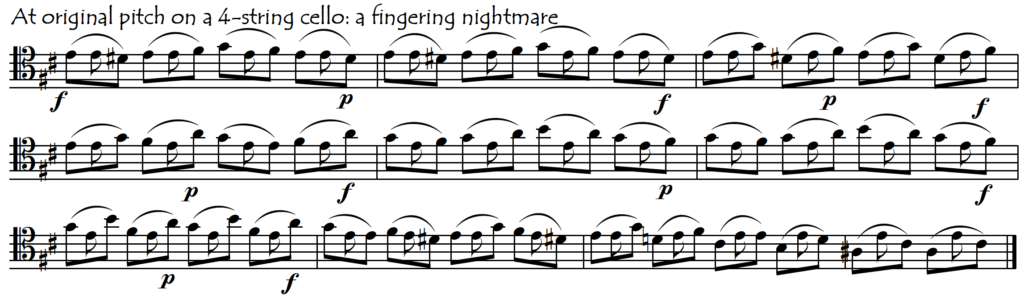

To resolve this problem for the modern-size cello, perhaps Bach wouldn’t object too strongly to the following solution:

Here, the “pedal” is the open G string instead of the open D string. This changes very little in the basic harmony because G is the tonic of the pedal chord (Bach’s original D is the fifth of the chord) but it is hugely advantageous for the cellist (and listeners). Using the open G string as the pedal we gain enormously in harmonic resonance because the open string can keep on ringing while we are playing the other notes of the passage, and we also gain hugely in technical ease (intonation security) because we can use thumbposition without now having to do a “lost in space” shift (removing the whole hand from the fingerboard) every time the pedal sounds. Purists and critics would hate this suggestion ….. but I rather like to think that Bach would approve. Bach was an eminently practical composer and it is hard to believe he would have deliberately written something that had such a high risk of sounding bad. His original version worked fine on the smaller instrument, but on a modern-size cello, independently of its number of strings, we need a little help with this passage. In the playing editions offered on this website, this modification of Bach’s original music has been used.