German Baroque: Phrasing, Rhetoric and Sewing Machines

In much of the music of the Baroque Period, notably in the music of Bach and Telemann, the lines of music sometimes seem almost endless. In the faster movements, the uninterrupted flow of equal note values can make the music sound sometimes a little mechanical, somewhat like a sewing machine (or a keyboard), especially when, as is often the case, there is a lack of articulation (slur) variety. In the slower movements, this same lack of rhythmic and articulation variety can create a certain feeling of lack of direction, of aimless rambling/meandering, and of not really making the most of the articulation possibilities of the bow (most notably through a lack of slurs).

This is why in Bach, Telemann, and Baroque music in general (more than in music of other periods), we often have to really search for and create the phrases by adding our own dynamics, articulations, bowings, and the rhythmical micro-freedoms of Rhetorical Delivery to give more structure and make more sense out of the ceaseless flow of notes. Playing the notes “well” is not usually enough and can sound like a boring teacher reading a textbook aloud to the class. In order to be really effective – to get the most out of the music – we need to apply a considerable amount of intelligence and creativity to these questions.

This music, especially when it is written for an unaccompanied melody instrument, is often a wonderful test of phrasing ability (and imagination) for performers. Not only do the notes come in constant succession with little rhythmic variety, but also the composers give almost no phrasing instructions at all apart from the occasional bowing. In fact, playing Bach is almost like an IQ test for musicians in which we are asked to “make as much sense as you can” out of long sequences of rhythmically identical sounds on a page. We do, however, run the risk of scholarly criticism. While taking rhythmical liberties (rubato) is normally considered an acceptable act of interpretation, adding and changing slurs is more controversial. If we consider the score as a “skeleton” or an “architect’s plan”, that can be dressed and decorated (played, articulated, bowed) in different ways, then we will not be obliged for eternity to always reproduce the composer’s articulation suggestions (see Urtext). In this way, our choices of bowings (slurs) can also be considered as part of our own personal interpretation.

BACH’S CELLO SUITES

The dance movements of Bach’s Suites (and Violin Partitas) usually have clear phrasing and a rich variety of articulations. Compared to the dance movements, the Preludes present a more difficult interpretative panorama, with less articulation variety and phrases that tend to be much longer and much less defined. Sometimes, hundreds and hundreds of notes of the same rhythmic value follow each other uninterruptedly, and to make the situation even more difficult, the notes are often given the same repeated articulation groupings over and over again. Bach was a champion of this type of music, and the Preludes of his Solo Cello Suites provide some very good examples of this rhythmic “monotony” that so desperately needs to be structured, organised and broken up into phrases:

- in the Prelude of Suite I, of the total of 657 notes, only 3 are not consecutive semiquavers.

- in the Prelude of Suite III, from bars 2 – 77 (i.e. the entire main section, between the introduction and coda) we have 895 uninterrupted semiquavers.

- the Preludes of Suites IV and VI start respectively with 384 and 930 consecutive uninterrupted quavers.

Even some of the dance movements are only slightly more varied rhythmically. Of the 84 total bars in the Courante of Suite III, 78 are composed of uninterrupted quavers (in four sections with 43, 162, 90 and 138 of them respectively). The only interruptions to this constant quaver movement are found in 6 solitary bars, in which we find a total of 8 semiquavers, 4 dotted crotchets and 2 minims (compared to the 477 total quavers in the movement).

Apart from the rhythmic monotony, there is sometimes also an “articulation monotony” that begs for more variety in the slurring and grouping of the notes. Sometimes we find ourselves faced with long sequences of separate notes which might benefit from the addition of a few short slurs, especially on arpeggio intervals across to a neighbouring string (see Choosing Bowings). The opening measures of the Courante from Suite II perhaps serve as a good example of this situation:

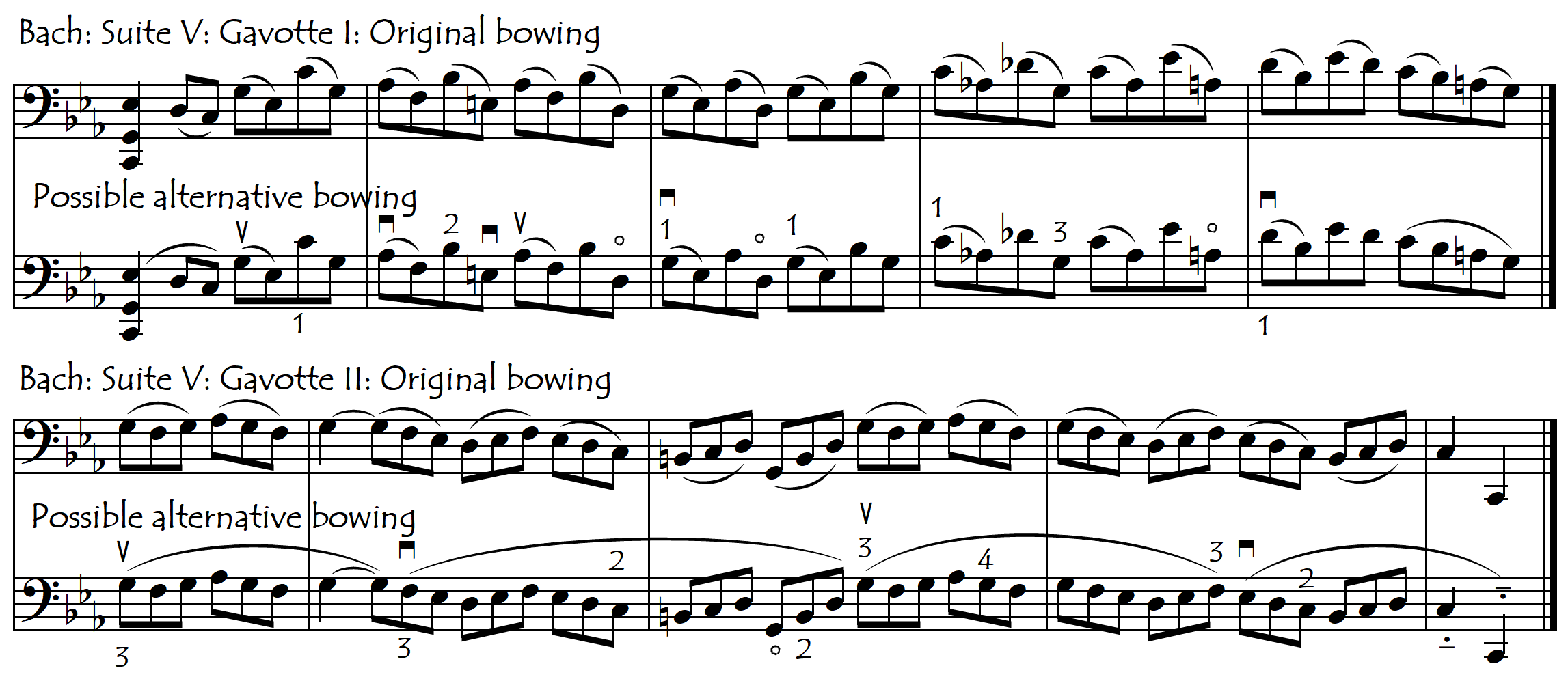

The monotony of unvaried articulations does not only occur with separate notes. Sometimes, Bach’s copyists unanimously suggest the same slurred note groupings over and over in passages where a little more articulation variety is not difficult to find and could add interest and colour. This situation occurs for example in Gavotte I from his Fifth Suite with the groups of two-slurred quarter-notes and likewise for the groups of three-slurred quarter-notes in Gavotte II:

A similar situation occurs in the Prelude to the Sixth Suite. Although there are inconsistencies between the four different source manuscripts, Bach’s apparent almost-constant slurring together of the groups of three notes can sound very boring and repetitive, which is a big shame for this absolutely wonderful composition.

BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED VIOLIN SONATAS AND PARTITAS

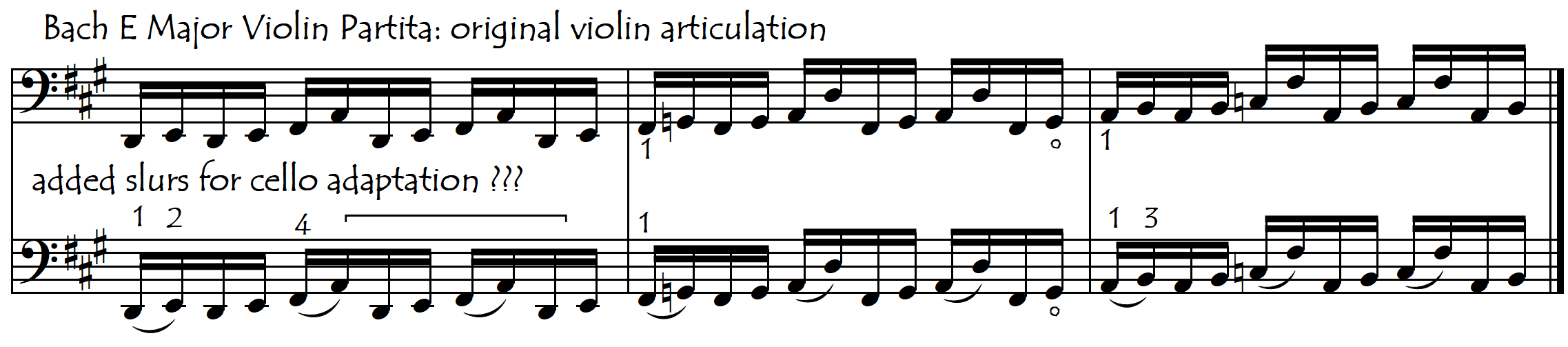

In the Prelude of the E major Violin Partita, of the total of 1629 notes, 1618 are semiquavers. Adding some small slurs can remove some of this “Moto Perpetuo” articulation monotony:

In Bach’s B Minor Partita for Solo Violin for example, five of the eight movements run a serious risk of sounding like the dreaded sewing machine because of the uninterrupted flow of equal note values as shown in the following table:

|

SEWING MACHINE RHYTHMS IN BACH B MINOR PARTITA FOR SOLO VIOLIN |

||

|

MOVEMENT |

TOTAL NUMBER OF NOTES |

NUMBER OF NOTES OF EQUAL RHYTHMIC VALUE |

|

Double I |

380 |

378 (semiquavers/16th notes) |

|

Courante |

476 |

474 (quavers/8th notes) |

|

Double II |

956 |

953 (semiquavers) |

|

Double III |

300 |

298 (quavers) |

|

Double IV |

532 |

531 (quavers) |

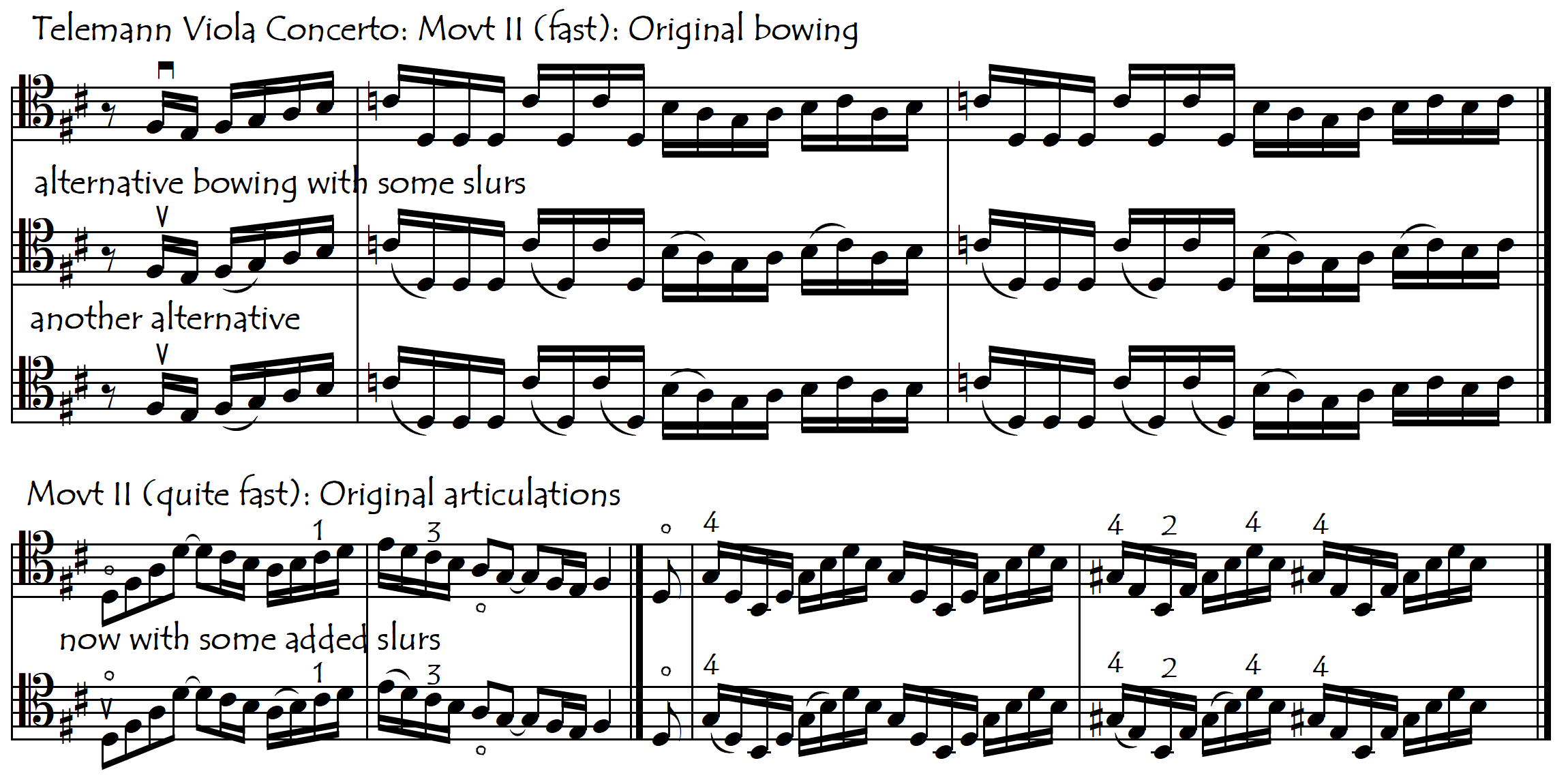

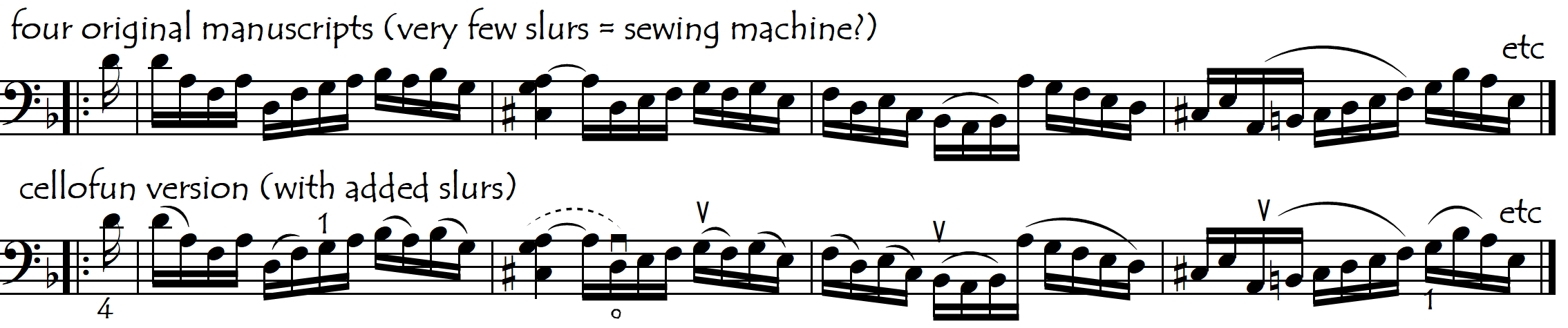

TELEMANN

In Telemann’s Violin Fantasias the risk of sewing-machine monotony is much less than in much of Bach’s solo violin music. Telemann’s phrases are shorter and, in general, there is more rhythmic and articulation variety. Nevertheless, we might still want to add a few slurs here and there to some of the passages in uninterrupted semiquavers and even also to some of the more lyrical passages in the slower movements in which Telemann doesn’t indicate slurs. In his Viola Concerto, there are several passages for which adding a few slurs to the uninterrupted fast semiquavers seems to improve both the interpretation and the ease of playing of those passages: