Bach: Rhythmic Factors

On this page, we will look at Bach‘s music for unaccompanied cello and violin from the point of view of rhythm. We will look at two main subjects: Bach’s use of dotted rhythms, and then his various rhythmical “curiosities”.

1. THE USE OF DOTTED RHYTHMS

The following table shows the frequency of use of dotted rhythms in the different movements of the different suites. Counting the dotted rythms can never be an exact process because the definition of what is (and what isn’t) a dotted rhythm is not actually completely precise, especially at slower tempi (see the article “Dotted Rhythms“). In this table therefore there are sometimes two numbers given for each movement. The numbers in brackets include the slower, “doubtful dots” which are however not included in the “total”.

|

FREQUENCY OF DOTTED RHYTHMS IN THE BACH CELLO SUITES |

||||||

|

SUITE 1 |

SUITE 2 |

SUITE III |

SUITE IV |

SUITE V |

SUITE VI |

|

|

PRELUDE

|

0 |

10 (16) |

0 |

3 (6) |

Prelude 44 (52) Fugue 2 |

0 |

|

ALLEMANDE |

18 |

14 |

3 |

0 (1) |

78 (82) |

33 (45) |

|

COURANTE |

3 |

2 (6) |

0 (4) |

0 (2) |

34 |

0 |

|

SARABANDE |

7 (9) |

4 (19) |

10 |

43 (44) |

0 |

31 (43) |

|

GALANTERIE I |

0 (2) |

0 (1) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

GALANTERIE 2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

GIGUE |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

63 |

0 |

|

TOTAL |

28 |

30 |

13 |

46 |

221 |

64 |

At slower speeds, dotted rhythms can give a mannered, courtly, lilting, even teasing (when you wait – to great effect – till the absolute last moment, before playing the short note) character. The Fifth Suite provides perhaps the best examples of this slow dotted “French style” in its Allemande and in the introduction to the Prelude. At faster speeds, dotted rhythms usually give a skipping, rollicking, sparkling, crisp, playful, dancing character. Once again it is the Fifth Suite that provides the best example of this in its Gigue.

FRENCH STYLE OR GERMANIC STYLE: OPTIONAL DOUBLE DOTTING

The use of dotted rhythms, especially in Baroque music, is often associated with the “French Style”. This is why we can consider the Fifth Suite as being very much in a “French suite”. Undotted rhythms, at any speed, give a more steady character. They can be slow and stately, or sprinting and driven, but are usually more “serious” and therefore referred to as “Germanic style”.

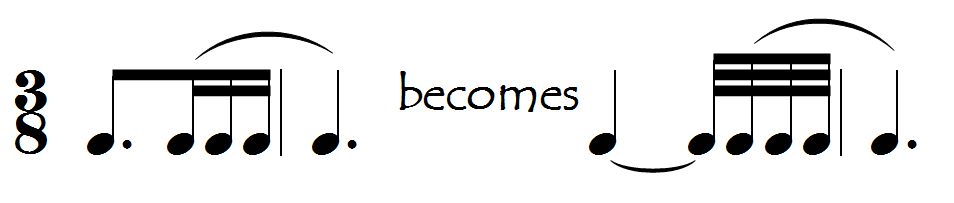

What really gives us a strong “French style” however is when we decide to “double dot” these dotted rhythms. This is optional, but was in Bach’s time perhaps an automatically assumed way of playing these rhythms, in the same way that we nowadays automatically (hopefully) play “swing” music syncopated even though is traditionally written out “square”. We can choose between playing in the German style (as written) or in this French double-dotted style in which the semiquavers (16th notes) are played later and shorter than written.

To illustrate this, let’s look at the Gigue of Suite V, whose 43 bars of classic 3/8 dotted rhythm can be even more “frenchified” and lightened by shortening the dotted note slightly as shown in the following example.

But we can make this movement even more dotted, sparkling and “French” by converting the semiquavers that lead into the next bars, into semidemiquavers as in the following example that occurs twenty times in this movement. Not doing this double-dotting will make the movement more plodding and heavy.

Independently of whether the movements are fast or slow, dotted rhythms tend to lighten the music, and this effect is heightened by the use of double dotting so prevalent in French Baroque music. Let’s look at how we can apply this to both the Prelude and Allemande of Suite V. Funnily enough, the rhythms in both examples are identical even though they come from different movements.

Independently of whether the movements are fast or slow, dotted rhythms tend to lighten the music, and this effect is heightened by the use of double dotting so prevalent in French Baroque music. Let’s look at how we can apply this to both the Prelude and Allemande of Suite V. Funnily enough, the rhythms in both examples are identical even though they come from different movements.

2. RHYTHMIC NOTATIONAL CURIOSITIES:

In some movements of the Bach Cello Suites (and Solo Violin Partitas and Sonatas), Bach writes the music using “bizarre” note lengths (time signatures). Sometimes – as in the Sarabande of the Sixth Suite and the Courante of the Fifth – he uses rhythmic values that would seem to be twice too long. This is the way pre-Baroque composers usually notated their music – see Purcell, Ortiz, Dowland etc – but it is unclear why Bach did this only in these two isolated movements.

Sometimes, he does just the opposite, using very small note values of half the length that we would normally expect. The Allemande of the Third Cello Suite is one example of this, with its 204 semidemiquavers (32nd notes, with three beams) but an even better example is the Allemande of the Sixth Cello Suite:

Bach’s notation of the Allemande of the Third Suite might look strange, with all those little notes, but is comprehensible when we realise that:

- with his notation, the speed of the quarter note (approximately 60 per minute) is more or less similar to all the other Allemandes of the first five suites (approximately 70 bpm

- the harmonic rhythm of this movement (see the harmonised Duo Version) is twice as slow as for his other Allemandes

The notation choice for the Sixth Suite Allemande is harder to understand because with Bach’s notation for this movement, it is now the eighth notes (rather than the quarter notes) that have a speed of 60 bpm. This is a similar situation to the Allemande of Bach’s First Violin Partita, which is also notated with tiny note values and has an eighth-note speed of approximately 45 bpm.

To try and understand why he might have done this, let’s have a look at some of his other unaccompanied string pieces for which he uses ultra-small note values. For this, we can use the Allemande of the first Solo Violin Partita, the Grave that starts the A minor Solo Violin Sonata the Adagio that starts the G minor Solo Violin Sonata and the first movement (Adagio?) of his Sonata Nº 3 for Violin and Harpsichord, as illustrated in the table below:

|

USE OF VERY SMALL RHYTHMIC VALUES IN BACH SLOW MOVEMENTS FOR CELLO OR VIOLIN |

|||

|

PIECE |

SEMIDEMIQUAVERS |

HEMIDEMISEMIQUAVERS |

SEMIHEMIDEMISEMIQUAVERS |

|

Allemande: |

363 |

56 |

0 |

|

Allemande: |

107 |

35 |

0 |

|

Adagio: Sonata I |

157 |

97 |

4 |

|

Grave: Sonata II |

280 |

55 |

0 |

|

Adagio: Movt I |

376 |

42 |

0 |

|

Allemande: |

204 |

0 |

0 |

This stuff is hard to read! We are not used to reading such small note values. Counting three or four beams on a note is as difficult (if not more) as counting many ledger lines on very high or low notes. Bach loved mathematics and reading this music is mathematically challenging for the normal musician. To decipher it we don’t even need our instrument: this is a mathematical exercise for which we just sit down with the music and a pencil to figure out the rhythms. Not only do all the beams make the music hard to read rhythmically, but they also make the music very “black” and complicated-looking.

This level of reading complication is however perhaps unnecessary. The only real usefulness of these tiny rhythmic values is to make it clear, perhaps, that the essential pulse of the music is very slow. The movements for which he uses this type of “microscopic” notation all have a slow pulse and long bar durations. If we write this music out using more readable note values (doubling the value of each note) we therefore have to be careful, when playing it, not to change Bach’s original idea. He obviously wrote it like he did in order that the piece would be felt (“danced”) with a very slow crotchet (1/4 note) pulse in which the short notes are simply light, fast-flowing, floritura ornamentations (like Baroque painting and architecture). Let’s play these movements like that, but let’s also make them readable without the need for a calculator or a magnifying glass!

All of these pieces (movements) are available on this website in both the original version and the “easy to read” version (with all note values doubled). To maintain their original ultra-slow bar frequency (pulse) we still maintain the original bar length despite the doubling of the note lengths. A dotted barline has been placed in the middle of each bar simply as a reference point, because these double-length bars can be extremely long.

To avoid having to decipher the pitch of notes far above or below the stave, editors normally don’t hesitate to change the clef or to use the “8ve” sign, but rewriting a composer’s rhythms in a more user-friendly way is not very common. This is a shame: for both pitch and rhythm, many reading difficulties can be easily avoided by simply using a more “user-friendly” notation.