Cello Thumbposition: Why Is It Hard ? What Are The Difficulties ?

There are many difficulties associated with the use of the thumb on the fingerboard (Thumbposition). Let’s look at them one by one:

1: UNCOMFORTABLE, UNNATURAL, AWKWARD AND STRAINED POSTURES

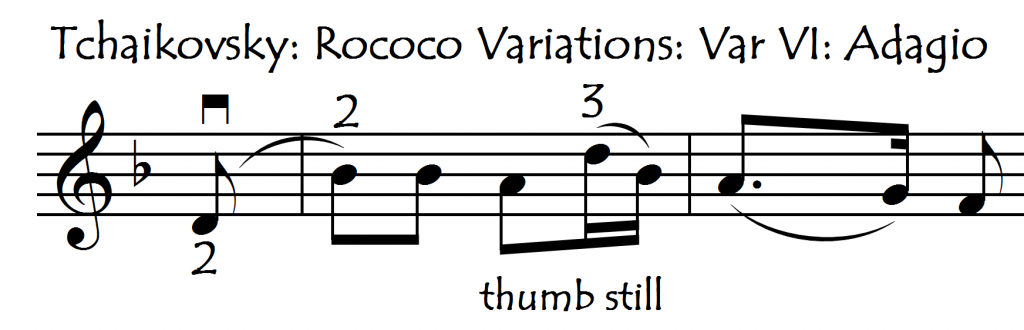

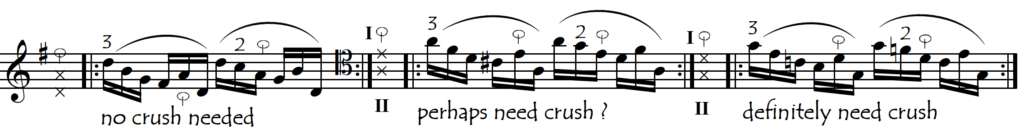

The first and most important problem is simply that it takes a lot of getting used to. Like a swimmer changing from freestyle (crawl) to the butterfly stroke, or like a ballet dancer going up onto their points, as soon as we place the thumb ON the fingerboard, the hand’s whole posture changes radically and we enter a totally different mechanical world. The hand in general, and especially the thumb, is just not used to this posture nor to these types of movements. With the thumb up on the fingerboard, even the simplest finger configurations can feel strange at first. For example, the whole-tone interval between the second and third fingers can feel quite clumsy at first:

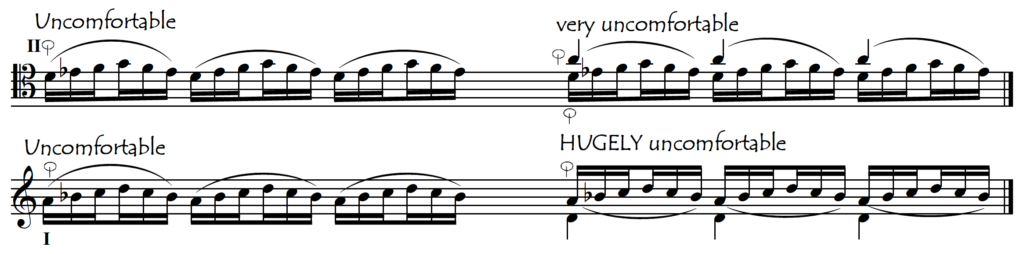

This 3-2 tone interval becomes increasingly uncomfortable as we go into the lower positions: try transposing the above example downwards by semitones to observe how it gradually becomes impossible. But other thumbposition finger configurations are even worse. Often, we are obliged to use hand postures in thumbposition that don’t just feel unusual but really are strange, strained and sometimes even wildly contorted. The next step in the progression towards increasing contortion occurs when the second/third finger whole-tone is combined with a whole-tone interval between the first and second fingers (giving a major third interval between the first and third fingers).

Now our hand discomfort increases even more, especially for small hands and especially in the lower thumb positions. In the above example, our thumb was comfortably placed one tone behind the first finger. One of the most uncomfortable thumbposition postures occurs when we take this same first/third finger major-third extension but now combine it with a semitone interval (crush) between our thumb and first finger:

This contorted hand posture is not only extremely uncomfortable (for small hands) but also extremely common. Sometimes we can avoid this awkward position by refingering the passage (as in the second example). These alternative fingerings can be useful in fast passages (as above) but are especially important in expressive passages in order to allow the hand to do vibrato. But often we can’t avoid these postures and will just need to adapt our hand to them through diligent practice. A more detailed look at these types of problems can be found by clicking on the Extensions in Thumbposition link and we will look more at the poor contorted first finger lower down on this page. For practice material for working on these uncomfortable finger configurations featuring major thirds between the first and third fingers, click on the following highlighted links.

Firstfinger/Thirdfinger Major Third: EXERCISES

Firstfinger/Thirdfinger Major Third With Thumb One Tone Behind: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

Firstfinger/Thirdfinger Major Third Together With Thumb/Firstfinger Semitone: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

The postural transformations required for thumbposition are difficult for the fingers, but even more so for the thumb. Nothing in a thumb’s previous life has prepared it in any way for this. In no other human activity is the thumb used in such a way. This is a very good illustration of the concept of “unnatural”. Our finger pads are full of millions of nerve endings which make them extremely sensitive and delicate sensory (and sensual) devices. As well as this wonderful, delicate sensitivity, millions of years of hanging and swinging from branches have also prepared our fingers perfectly for the cello, as this is exactly the posture we use for the left hand ……… in the neck positions. (See Finger-String Contact)

But in contrast to the fingers, those same millions of years of evolution for the thumb have produced a very functional and strong (but relatively brutal) instrument for gripping branches, tools and enemies’ necks. Unfortunately (for the thumb), playing the cello does not require these otherwise very useful skills – quite the contrary in fact ! Suddenly, at the cello, the thumb is not only told “DON’T GRIP” but now also “PUSH DOWN AWAY FROM THE PALM” and then “WOBBLE RHYTHMICALLY” (vibrato)! Poor thumb. Is it really surprising then that cellists traditionally consider thumbposition “difficult”, mainly for virtuosos, and leave the high regions till last in cello pedagogy?

WHY IS THUMBPOSITION UNCOMFORTABLE ?

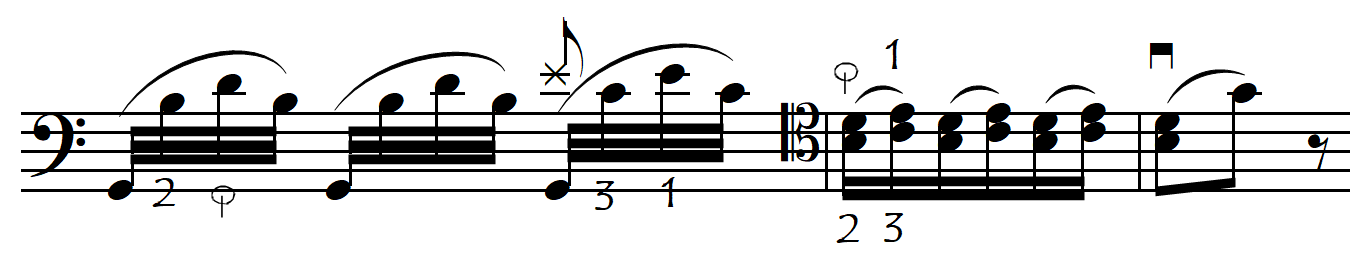

It is actually the shortness of the thumb that causes most of the difficulties of thumbposition. Because of this shortness, placing the thumb ON the fingerboard automatically tips the hand backwards into the “violin” position (with the first finger very curled). The more strings the thumb is covering (touching), the more it turns the hand, making the fingers slope backwards and placing them diagonally to the strings and fingerboard. This is not a comfortable playing position – especially for the first finger. For this reason, if we have the thumb on the G and D strings, it becomes more difficult to play with the (other) fingers on the A string. Thus, in order to play comfortably on the A string in thumbposition, we usually need to bring the thumb over to the top two strings even if it is not actually being used to play any notes in the passage. Sometimes however this is not possible (or too complex to be worth it).

Saying the same thing but in other words, the fewer strings we have the thumb on, the more the fingers can be square to the fingerboard (like our hand posture in the Neck Position) which makes just about everything easier for them. Cellists with long thumbs have a great advantage in this sense as their left hand is able to stay more square to the fingerboard in thumbposition, which considerably reduces the tension in the hand (the first finger need not curl up so much, it is easier to extend up to the higher fingers etc). To achieve this same effect, cellists with short thumbs may thus find it especially useful, where possible, to play with the thumb only on the higher string – or even floating completely free (see discussion below). The added comfort and relaxation that this gives us is especially noticeable in fast passages, but also in lyrical passages requiring simultaneously extensions and a warm free vibrato. Try the following passages with the thumb firstly on both A and D strings and then on the A string alone.

RELEASING THE THUMB TO MAKE THE POSTURE MORE COMFORTABLE?

Having the thumb only on the A string is already useful, but releasing the thumb entirely (when it is not needed to stop a note) frees the fingers up even more. Imagine if in the Neck and Intermediate Regions we always had to keep our first finger down ?? Try it …. This creates unnecessary and harmful tension. If we watch videos of Yo Yo Ma, Stephen Isserlis and other fine cellists, we will see that they often release the thumb in the higher regions, letting it float in the air until it is actually needed to stop a note. This increased comfort not only allows a bigger vibrato but also helps in faster passages, especially for small hands.

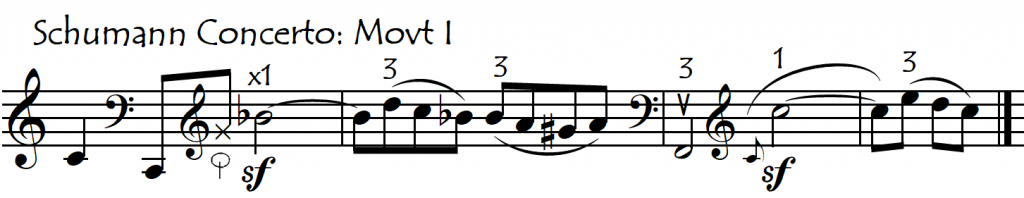

This is particularly noticeable in fast upward scales on one string (especially on the A string). This is because the first finger is, especially for small hands, often uncomfortable and strained if held down while the third finger or extended 2nd finger (one tone from the first) are stopping the string. Shifting quickly and comfortably up to the first finger after a higher finger is so much more difficult if the first finger is under strain before the shift. Removing the thumb removes part of this strain, thus facilitating the comfort and security of the shift, as in the following examples:

IN-TUNE FIFTH ON THUMB REQUIRES UNERGONOMIC HAND ANGLE

In thumbposition, the angle of the thumb required for an in-tune fifth across the A and D strings poses serious problems for our hand’s ergonomy. For a perfectly in-tune fifth across the A and D strings, it seems that the thumb needs to point back towards the scroll of the cello. With the thumb pointing towards the scroll, the fingers (especially the lower ones and especially on the higher string) are obliged to curl up into an even more uncomfortable posture, which supposes a great hindrance to all aspects of our left-hand technique. If the tip of the thumb could be pointing the other way (towards the bridge) then this would constitute a help for our hand’s ergonomy. Unfortunately, the great majority of our thumbposition playing occurs on our top two strings, making this “unergonomic” fifth angle across those two strings seem like a very cruel act of destiny/nature/physics!

This is especially problematic when we need to sound the thumb on both strings in a passage because the perfectly in-tune perfect fifth requires the highly unergonomic thumb angle that makes life so difficult for the rest of the hand. If we are only sounding the thumb on the top string, then when can position it (angle it) in such a way that it facilitates the ergonomy of the other fingers.

In order to obtain our perfectly in-tune fifth on the thumb we may need to turn the hand so much that our first finger needs to go into one of two quite unergonomic positions:

- totally curled, stopping the string by pushing it sideways across towards the left with the tip of the finger, or alternatively

- with the last two joints totally blocked, rigid and straight

But even without needing to play a perfect fifth on the thumb, we can find ourselves, especially in the Neck Region, with our first finger in this bizarre posture. It is enough to have the third finger on the lower string and the first finger on the higher string:

Let’s look now in greater detail at this bizarre first-finger posture:

FIRST FINGER ABSOLUTE CONTORTION

Sometimes we will need to use a very bizarre posture for the first finger in which it is totally curled and pushes against the string horizontally instead of vertically. This need occurs when we have the third finger on the lower string and the first finger on the higher string, especially (but not exclusively) when the thumb is only a semitone away from the first finger.

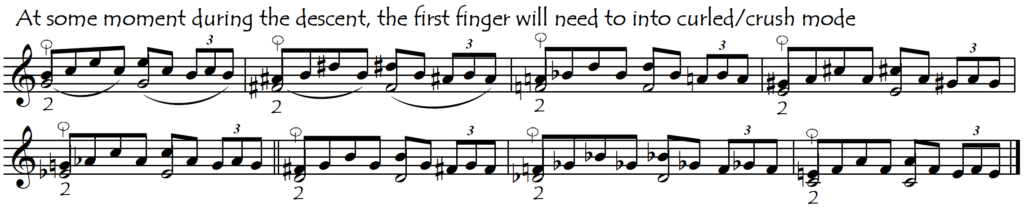

The lower our hand is on the fingerboard (pitch-wise) the greater the need for the contortion. In the following progression, we can see how at some point in our descent, the first finger will need to go into the totally curled position:

Even when there is a whole tone between the thumb and first finger, as we go lower on the fingerboard eventually we will also need to use this contorted, curled, crushed sideways first-finger posture:

This bizarre first-finger posture is only useful in faster passages where we don’t need vibrato on that first-finger note:

GENERAL DISCOMFORT OF FIRST FINGER

The first finger in the Neck and Intermediate fingerboard regions is the hand’s powerhouse, foundation and pillar of strength. But when we place the thumb up on the fingerboard that same first finger suddenly loses most of its superior qualities, becoming weak and insecure. This is because it is just too close to the thumb for optimum stability/ergonomy. The problem is especially pronounced on the A-string because the obligatory hand position – especially for cellists with a short thumb – means that the first finger doesn’t have room to have its nice ergonomic curve and must play often with the last finger joint blocked in a rigid, straight line. Strong climactic notes played on the first finger in thumbposition on the A-string can be quite unsatisfying because of this unergonomic finger posture:

And big shifts up to supposedly powerful notes on the first finger can be dangerously unstable.

Usually, it is this first-finger weakness and instability that causes the main problems with upward scales on the same string in thumbposition:

For all these reasons we need to work especially on our first finger strength in thumbposition. The Cossmann Doubletrill exercises, together with first-finger shifting exercises are very good for this. Upward scales on one string also work the strength of the first finger very much. Apart from this “hard physical work”, some other easier solutions (using our intelligence) are also available. Placing the thumb only on the A-string can help facilitate the comfort of the first finger, thus minimising this problem somewhat. Removing the thumb entirely from the fingerboard (allowing it to “float”) does even more to help.

ARM DISCOMFORT

Thumbposition is not just uncomfortable and hard work for the fingers, thumb and hand. Maintaining the arm in the higher positions also requires more muscular effort than in the lower positions as the arm is extended (reaching up) and the elbow is raised. In the lower positions, the left arm is closer to the body, which allows its muscles to be more relaxed. It is as though in the lower positions we were sitting (or lying) down on a comfortable sofa, while in the higher regions we are standing up (sometimes on the tips of our toes and on a high stool).

GREATER STRING TENSION AND HEIGHT: THE NEED FOR A THUMB CALLOUS

Another problem with playing in thumbposition is the increasing difficulty of stopping the strings (pressing them to the fingerboard) as we go further and further above the strings halfway point. This difficulty is due to two factors.

- the increased (and sometimes excessive) height of the strings above the fingerboard in the higher regions (many luthiers do not pay enough attention to this region)

- the increasing rigidity (difficulty of moving) the strings as they get closer and closer to the bridge (this is discussed in more detail below in the section concerned with sound and bowing difficulties)

This difficulty in stopping the strings in the higher regions is especially significant for the thumb (as compared to the fingers) for two reasons:

- it is the thumb pressure that normally maintains the strings permanently close to the fingerboard when we are playing in thumbposition. In other words, it is the thumb that does the hard, brutal work of the guitar’s “capo” which thus allows the fingers to be able to do their “artistic work” of articulating fast and freely as well as vibrating (none of which the thumb can do much of)

- the thumb is not used to applying pressure in this direction, nor is it used to resisting the abrasive forces of the string on the skin

Not many thumbs are able to function well in thumbposition without a considerable callous on that inner part of the thumb that stops the higher string (the outer part which stops the lower string is protected by the thumbnail and thus doesn’t need a callous). This callous is necessary for two reasons:

- to stop the string cutting into the thumb when playing with the thumb for longer amounts of time

- to help the thumb stop the string firmly and cleanly. Without a thumb callous, the higher string just makes a deep groove in the soft skin and is no longer stopped properly, which causes all the different problems that we get in any situation where the finger pressure is insufficient: a consistently bad sound (with occasional squeaks) and bad intonation on the thumb notes.

The callous needs to be built up gradually, and then maintained by regular thumb use. Playing suddenly for a long time in thumbposition will almost certainly cause an abrasion injury on the skin of that part of the thumb that touches the higher string and to minimise this risk we need to be careful that our strings are not set too high. The A-string is the most “dangerous” string in this regard because it is the thinnest: the lower strings are thicker and for this reason they don’t cut into the skin anywhere near as much. It’s a bit like the difference between being walked on by someone wearing stiletto heels (A-string) or by someone wearing normal shoes (lower strings).

If we gradually increase the time we spend using the thumb, the callous will form naturally. But if we don’t have these optimal conditions of gradual build-up then there are several ways in which we can avoid the situation in which the skin becomes so sore that we have to stop using thumbposition:

- at every opportunity, place the thumb only on the A-string (instead of on both the A and D strings) as the presence of the thumbnail serves as a protection for the skin in this area. The following exercises, for example, can be played with the thumb only on the top string:

Basic Thumbposition Exercises On One String

- practice passages only on the three lower strings (with no thumb-use on the A-string)

- put a plaster over it

If we really overdo it, serious muscle and joint problems can be the result for the thumb, so it is in fact quite fortunate that the skin damage (and pain) starts long before these more serious problems.

The callous that is necessary to be able to use the thumb well on the cello is visible proof that thumbs were not originally intended for anything even remotely like this. But we need to remember that with the softer and more flexible gut strings that Boccherini and co. would have used, this problem would have been significantly less important than nowadays with our tight steel strings.

2: LOST IN SPACE

The second main problem of playing with our thumb up on the fingerboard is the lack of positional references. This means that we can often feel pretty much “lost in space” in thumbposition. Several factors contribute to this:

2A. in the neck region, our hand is moving between two very clearly defined reference points. The “corner” at the top of the neck (“4th position”) serves as one limit, and the end of the fingerboard (scroll-end) serves as the other limit. We are constantly sensing the distance of our left hand from these points, and we use this information to know where we are on the fingerboard. By contrast, in the thumb region, there are no easy visual or physical reference points to help us know where we are. Thus, when we are playing in thumbposition we often find the next note according to its interval from the previous one rather than from a clear idea of its absolute location (see Positional Sense). In other words, we often don’t know exactly where we are up there until we have actually sounded (played) a note, and worked out which one it is. Then we orientate ourselves in relation to that note, which has become our reference for the moment.

2B: The further up the fingerboard we go, the further away our hand is from our body and the greater our elbow/forearm angle becomes. Because of this, as we go up the fingerboard it becomes progressively more difficult to sense exactly where our hand is, and the greater the margin of error becomes in our fine positional controls.

2C: When the thumb is under the cello neck (as in normal Neck Position), or in the angle at the upper corner of the neck (as in the Intermediate Positions) it gives us a lot of positional information. In other words, we know what notes our fingers are going to fall on mainly thanks to the positional information from the thumb (try finding different notes with the thumb not touching the cello neck and you will see how difficult it is to know where our fingers are without this information). But as soon as our thumb is on top of the fingerboard, it loses this ability to tell us where we are. Playing in thumbposition we can feel “lost in space” even in the lower (neck) regions. I must confess that I don’t know why this is ……… but it is !

3: SOUND (BOWING)

A third problem is the difficulty in making a good sound in the higher regions. This is principally a bowing problem. It comes from the fact that as our left-hand stops the string higher and higher up the fingerboard, the length of the vibrating string becomes shorter. This in turn requires that, in order to make the string vibrate properly, the bow must go closer and closer towards the bridge (click here for a simple exercise to automatise this). Unfortunately, the rigidity of the strings increases closer to the bridge, which means that as the string gets nearer to the bridge, the string becomes exponentially more difficult to move (to both set in vibration and to keep in vibration). This means that, as we bow closer to the bridge, it becomes more and more difficult to find the right mix of bow speed and pressure necessary to make a good sound.

4: THUMB VIBRATO: Thumb vibrato has its own dedicated page here.

5: TRILLS ON THUMB

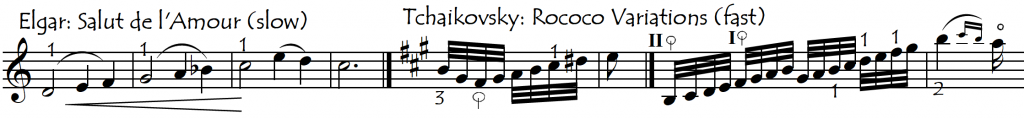

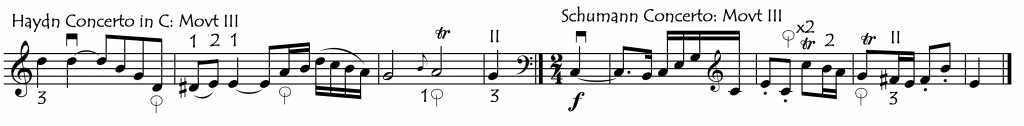

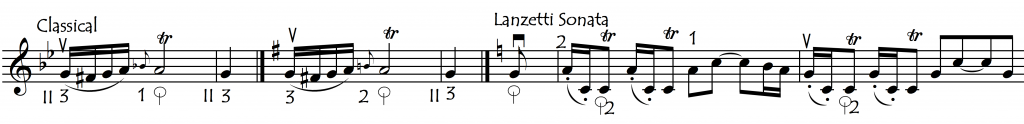

These are not very enjoyable and are only to be used when any alternative fingering would be even worse (which unfortunately is quite common). If the thumb can be played as a harmonic then this trill becomes somewhat easier (as in the first of the following examples):

The semitone trill is easier than the whole-tone trill because of the greater compactness of the hand. For the same reason, using the second finger (instead of the first finger) as the trilling finger for one-tone trills on the thumb gives much greater speed and stability even though it may seem a bizarre fingering.

The semitone trill is easier than the whole-tone trill because of the greater compactness of the hand. For the same reason, using the second finger (instead of the first finger) as the trilling finger for one-tone trills on the thumb gives much greater speed and stability even though it may seem a bizarre fingering.

This is however not always easy to do:

This is however not always easy to do:

***************************************************************

SOME CONSEQUENCES OF THE DIFFICULTIES OF THUMBPOSITION:

The difficulties of cellists in thumbposition were accepted and respected by composers. But most composers did not understand the causes of these difficulties. They thought that we cellists were like singers …….. or mountaineers ………..or fruit. For singers (and also for wind and brass players), a high note requires much more muscular effort than a low one, thus staying up high for too long strains the voice. For mountaineers, the higher they climb, the less oxygen there is in the air, and the harder everything becomes, which means that they need to get back down afterwards as quickly as possible.

And fruit ? According to common legend, Newton discovered gravity thanks to an apple falling on his head. Fruit – like everything else, including mountaineers – tends to fall down to earth, and falling is dangerous: for the person underneath the falling object (Newton) as well as for the faller (mountaineer).

For all these reasons, in most cello music of the classical and romantic eras, the composers usually only send us up to the higher regions for a few brief culminating moments. This is a great shame because it means that we never really spend enough time up there, in most standard repertoire at least, to get properly acclimatized to the higher altitudes. And this lack of comfort in the high regions means that many of these culminating, emotional, or dramatic moments are also unfortunately the passages that most trouble us and are the most likely to be played badly.

It’s also a shame because they (the composers) were mistaken. The cello is neither a voice, nor a mountain, nor a fruit. None of these conditions apply to cellists’ left hands.

- a high note on the cello does not require much more muscular effort than a low one (unless the strings are too high from the fingerboard).

- there is no shortage of oxygen up there and thus no urgent need to get back down as soon as possible

- there is no risk of a catastrophic fall from the higher positions. Gravity does not make our hand fall back to the low positions but rather the complete opposite. The words “up” and “down” on the cello fingerboard mean in fact the complete opposite of what they mean in normal life. What we call the “higher” positions are only high in the musical sense. The “higher” our hand goes up the cello fingerboard, the higher the notes get but the CLOSER our hand gets to the ground. In a strictly scientific, spatial use of language, our hand actually gets lower to the ground as we go up the fingerboard.

Had he learned the cello as a child, Newton probably would have become very confused about the concepts of up and down …… and might never have discovered gravity. And we haven’t even mentioned yet the equally illogical concepts of “up” and “down” bow directions!