Ricochet and Flying Spiccato (Jeté) On The Cello

Often we need to play the cello as though we were a singer, but occasionally we need to open up our box of magic tricks, unwrapping our ricochet and flying spiccato bowings to become more like jugglers or circus acrobats. In both of these bowing styles, the bow bounces several times in the same bow direction, rather like skipping pebbles on water. What then are the differences between ricochet and flying spiccato ??

- ricochet tends to be faster than flying spiccato

- ricochet can be played equally well on upbows as on downbows whereas flying spiccato is used almost exclusively on upbows

- ricochet has only one impulse in each direction, no matter how many notes are played within each bowstroke, whereas flying spiccato has more of a conscious, deliberate impulse for each note

- ricochet starts with a clear throwing of the bow against the string whereas flying spiccato can start with the bow still on the string after a previous note. Because of this obligatory throwing impulse, ricochet is also often given the french name “jeté” which in french means literally “thrown”

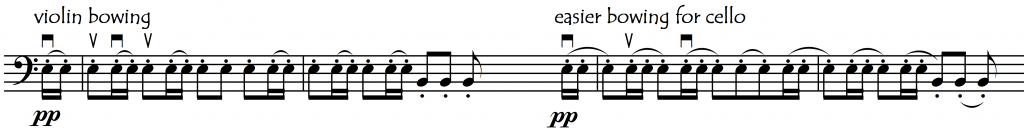

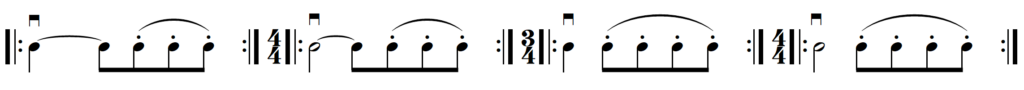

These two bowing styles are virtuoso versions of spiccato, in the same way that flying staccato is a virtuoso form of portato. If we change our bow direction after every bounce then this is no longer “ricochet”, but rather just a plain old “spiccato” as in the following example:

The discussion and examples that follow below will look at these questions in more detail. Before looking at ricochet, let’s start with flying spiccato as this is the slower version of the flying bounce.

FLYING SPICCATO

Even though we might think of flying staccato as a virtuoso technique, we actually use it very often in its simplest manifestation as two upbow spiccato notes:

These are very commonly-used bowings for two reasons:

- the two short (staccato) notes tend to be shorter(more staccato) than if we were to use as-it-comes bowings

- they give us the strong beats always on the downbow, which usually feels more natural

To verify these characteristics, try the above rhythmic figures now with as-it-comes bowings instead of the two flying upbows:

The most common manifestation of these bowings is with the two upbows on the upbeat and the downbows on the strong beats. Having our two flying upbows on the strong beats can be a little disconcerting because we are bowing “against the beat”, but it still gives us the advantage of the extra-short staccato, compared to the “as-it-comes” bowing:

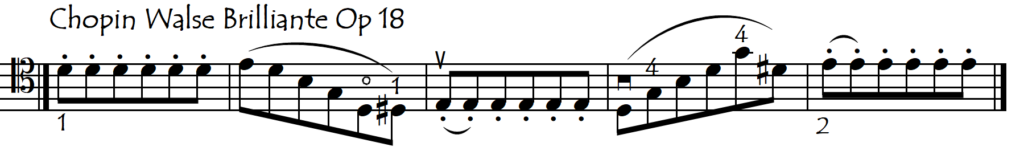

If the note before our flying upbow is long, then we can (or must) start our flight from on the string. Especially in faster tempos, getting the bow to bounce can require a very agile and well-trained hand:

If the previous note is short however, we can (and will almost certainly want to) start from above the string. Starting our flying spiccato from above the string guarantees the bow’s bounce but can be a little harder to control

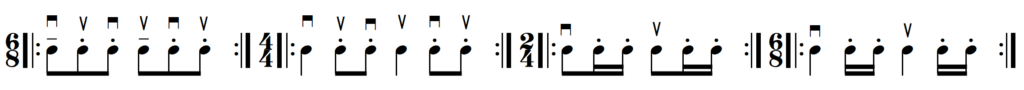

In all of the above flying spiccato examples, we have only two notes on our flying upbow. This is the easiest version. As we add more notes to our upbow, the difficulties increase:

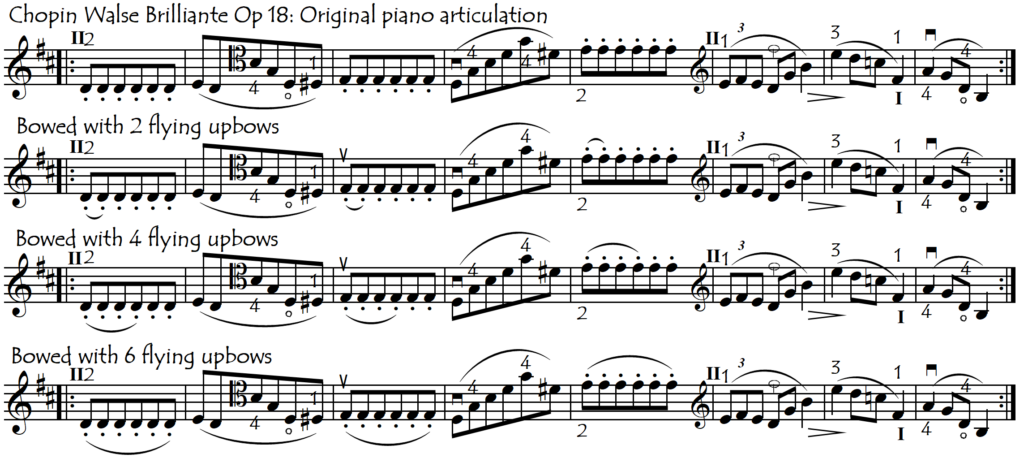

Often, we have a choice of how many notes to play in our flying upbow. According to the difficulty and speed of the passage, as well as the length of the downbow note before our flying upbow, we might want to include fewer (or more) notes within the flying upbow stroke:

Flying Spiccato: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

As the speed of the bounce gets faster, we will eventually reach a speed at which our flying spiccato becomes unstable, then dangerous and ultimately, impossible. To avoid these problems, at some stage (speed) we can start to use ricochet instead of flying spiccato. So let’s look now at the fastest variety of flying spiccato: ricochet bowings:

RICOCHET: WHEN AND WHY?

Ricochet bowings are used when:

- the speed of the notes is so fast that any other bowings – flying or normal (alternating bow-direction) spiccato – would just get us in a tangle, or

- we want to achieve exceptionally brilliant, fast, short, highly articulated sounds in figures that could be played with normal spiccato

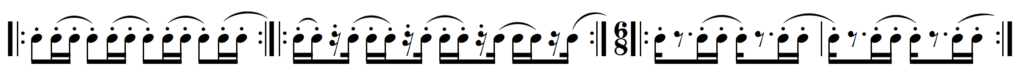

Above a certain speed, with flying spiccato we are no longer able to control each bounce and will probably need to use ricochet bowings:

They only work in quite limited situations: repeated series of rhythmical ricochet bowings are applied normally to small groups of notes – anything above 4 notes per ricochet is starting to get very tricky – usually without many left-hand-finger changes within each ricochet “throw”.

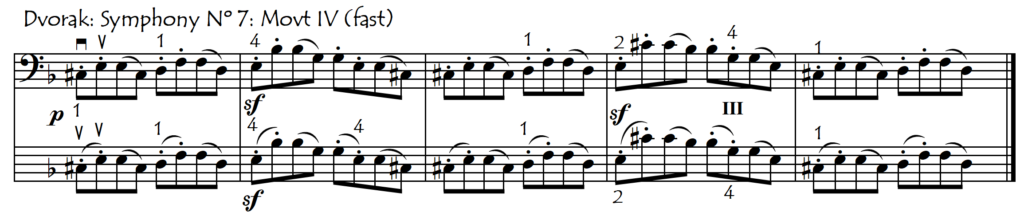

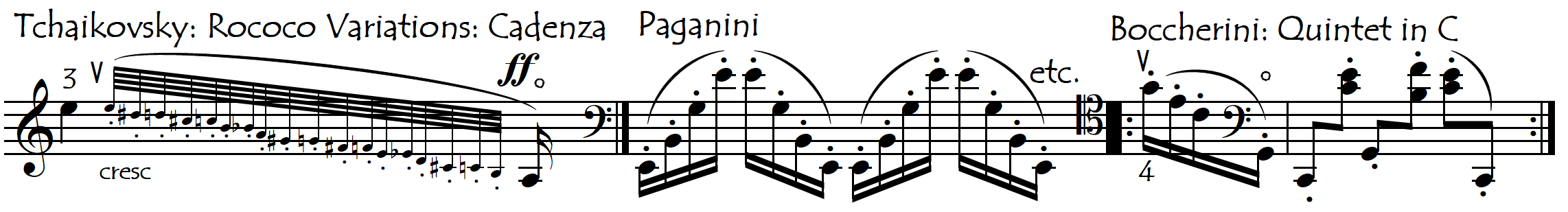

If there are many finger changes, ricochet can seem difficult because the rapid coordination of the finger changes with the ricochet bounce is not easy. This doesn’t however mean that we can’t have a lot of note changes in one ricochet bowstroke:

In the first two of the above examples, the pitch changes don’t require lefthand coordination. In the last example however, Boccherini combines, in the same single ricochet throw, lefthand finger changes with string crossings. This is why this little figure is quite a tricky, virtuosic coordination exercise!

Thanks to the very clear bowing articulation given by the thrown bounce, even when the coordination is difficult because of finger changes during the flying spiccato, the passage still might sound clearer and more brilliant than if we were to play the same notes slurred:

Ricochet is a type of bowing that is rarely used in the standard solo cello repertoire, which is why we rarely work on it systematically. Surprisingly however (for what could be considered as quite a brilliant, virtuoso type of technique), we need it reasonably frequently in orchestral music and even in chamber music. If we are not familiar and comfortable with doing this type of bowing, we can easily find ourselves losing our rhythmic control in passages that would not pose a significant problem if we were to play them with a normal spiccato bowing. Click on the following link for a compilation of repertoire examples using ricochet bowings.

Ricochet gives a special type of sound- very short, articulated and percussive – that composers may or may not specify. We can use our cellistic and musical judgement to decide whether or not a ricochet bowing is the best alternative in any situation. Certainly, we will need to use our judgement as to which ricochet bow directions are the most suitable for each figure because this is a subject for which most composers are not well placed to decide, and if they do specify the exact bowing they often get it wrong (usually basing their choice of bowing on what suits the violin [see below]).

PERFECTION, DISASTER, OR SUBSTITUTION BY SPICCATO

Even though it may be the “extreme sports” version of spiccato, ricochet is actually a very delicate and tricky bow stroke: it either works easily and naturally, or is a chaotic out-of-control mess. Because ricochet bowings are used in fast delicate passages with absolutely crystal-clear rhythms, we normally cannot hide or play them “approximately”. They are either perfect (and easy) or highly embarrassing, so we really need to feel comfortable and secure with this technique. If we are not secure with our ricochet, it is probably best to just play the figures with a normal spiccato: it is better to sacrifice a little bit of character (and the cello section’s visual uniformity) than to mess up the rhythm completely!

WHAT ARE THE UPPER AND LOWER SPEED LIMITS FOR RICOCHET?

If we look at the note speeds in different repertoire passages using ricochet we will see that a fairly common npm (note-per-minute) speed for ricochet is somewhere around 600-700 with an upper limit of 800-900 and a lower limit of around 500. Below a certain speed, we will probably want to articulate each note individually with the bow, and above a certain speed, the bounces are no longer clearly distinguishable/discernible.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE ELBOW IN RICOCHET

The importance of the elbow in our control of ricochet is surprising. Freeing up the elbow, allowing it to move in both preparation and follow-through, makes ricochet bowings suddenly much easier and more natural. The more bow changes we have in the ricochet passage, the more this flowing relaxed mobile elbow will be necessary/helpful.

DIFFERENT BOWINGS FOR VIOLIN AND CELLO RICOCHETS

The violin bow is lighter and easier to control than the cello bow in ricochet bowings. For this reason, cellists may prefer to change their bows less often than violinists in ricochet figures, especially in that most common of ricochet rhythms: two 16th notes followed by an eighth note, as shown in the following (in)famous example from Rossini’s William Tell overture. Unfortunately, in orchestras, the bowings come initially from the concertmaster (violinist) so we may end up having to play those violin bowings ……..

RICOCHET AND DYNAMICS

Ricochet bowings are most common in the softer dynamics. For louder playing, we usually favour a more vigorous, energetic spiccato, with one note per bow stroke, as for example in the accompaniment to Shostakovitch’s First Cello Concerto. In the first two examples below, played softly, we could use a ricochet bowstroke, whereas in the last “forte” variant we will definitely use separate spiccato bowstrokes:

It is very easy to invent ricochet practice material. Simply playing any sequence of notes (the easier the better) with standard ricochet rhythms and bowings, will get us used to controlling this delicate bowstroke.