Fast and/or Tricky Playing: Speed and Coordination

WALK, JOG OR SPRINT?

Runners, swimmers, skiers and many other athletes can decide whether they want to specialise in marathons or sprints. We musicians don’t have that choice: we need to be able to do the musical equivalent of both. Playing lyrical slow melodies beautifully is a huge and essential part of a cellist’s required skills but we also need to be able to do the high-speed stuff – and those sprints and pyrotechnics very often come immediately after (or before) the lovely slow stuff!

The cello is quite a large, cumbersome instrument and is not ideally suited to high-speed virtuosity. Compared to the violin, saxophone, clarinet, and many other more virtuosic (fast-response) instruments, not only are the distances between the notes on the cello greater but also the instrument speaks slower (with more energy/effort required to articulate each new note). Taking an analogy from the world of motor vehicles, the cello would be somewhere between a truck (double bass) and a Ferrari (violin) – so perhaps a camping van (RV)? In the animal world, it would be somewhere between an elephant and a hummingbird: a large sheep (or a small cow) perhaps??!!

LONG AND FAST OR JUST A QUICK TRICK?

“Fast” is a very interesting and wide concept. When looking at the problems posed by a “fast passage” we need to differentiate between the different types of problems that fast playing can pose. Some fast passages are very short, with only a few fast movements following on from each other rapidly in succession. Rather than “fast passages” we probably think of these as “tricky bits”. Here the main problem is the rapid coordination of just a few different movements. At the other extreme, we can have longer fast passages, in which problems of endurance, reading, memory and inner visualisation are added to the speed/coordination requirements. And mixed in with these “difficult” fast bits there are other moments (notably tremolo and slurred trills) when we play very fast but without any difficulty whatsoever (see below).

THE BENEFITS OF FAST PLAYING

Practising slowly and with the utmost relaxation teaches us a lot, but fast-playing also teaches us many useful things, most notably:

- to be relaxed (otherwise we will seize up along the way)

- to let go and trust our body’s automatic programming (because at high speed it is impossible to consciously play/think every note individually)

- to read quickly, and to read ahead of what we are playing (if our eyes can’t read fast enough, there is no way our fingers will be able to play fast enough)

Fast-playing is in fact a great and infallible diagnostic tool for our level of tension in much the same way as the proverbial canary in the coal mine used to be a diagnostic tool for the level of toxic gases. While the canary would die if the toxic gases built up, thus warning the miners that it was time to get out, our fast-playing will seize up if our level of (toxic) tension is too high, thus warning us that we need to find ways to reduce our tension level, normally through improving our “technique”.

Driving a vehicle fast and out of control is scary, but when we can do it calmly, without losing control, it gives us a great feeling of mastery. The situation is identical on the cello although the danger, in case of a crash, is purely psychological. But playing fast not only gives us a feeling of mastery: to be able to play fast without crashing or seizing up we actually need mastery as a pre-condition. Fast-playing is thus not only a great diagnostic tool for our level of tension at the cello but is also probably the ultimate test of our mastery of the cello.

While fast-playing “teaches” us many essential skills, prolonged fast exercises, studies, and pieces (Moto Perpetuos) also give us one of the best possible physical workouts for developing the invaluable endurance strength and fitness that make normal-speed playing ultimately seem effortless.

THE PRACTICAL STUFF

In this article, we will have a detailed look at some of the different concepts and difficulties involved in “fast” playing, but for those of us who want to get immediately into the more practical, playing side of things, here are some links to practice material, as well as to some practical tips and tricks concerning how to play and practice fast passages. The subject of how to play fast and how to improve our “fast bits” is an enormous and very important part of our technical toolbox so it has its own dedicated page.

Tips For Practicing Fast and/or Tricky Passages

Almost every longer piece of music has its “fast passages” so there is a vast abundance of practice material to choose from. Click on the following link for a selection of exercises and repertoire excerpts, grouped according to the type of difficulties involved.

Fast and Tricky Playing: EXERCISES AND REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

And now, for the more curious, let’s continue with our investigation of some of the different concepts of what “fast” playing really is:

SPEED MEASUREMENT

When analysing speed-based problems it is useful to be able to somehow measure the “speed” at which our notes are happening. For vehicles, we measure their speed by the distance travelled over a certain time (km/hr) but this is not at all useful on musical instruments (except perhaps for the double bass!). If we go inside the vehicle, to the engine, we start to get closer to a useful measuring concept with rpm (revolutions per minute), which when transposed onto a musical instrument would be bpm (beats per minute) or, even more useful for us, npm (notes per minute). So how fast is fast according to these measures, in music and, more specifically, on the cello?

SPEED LIMITS

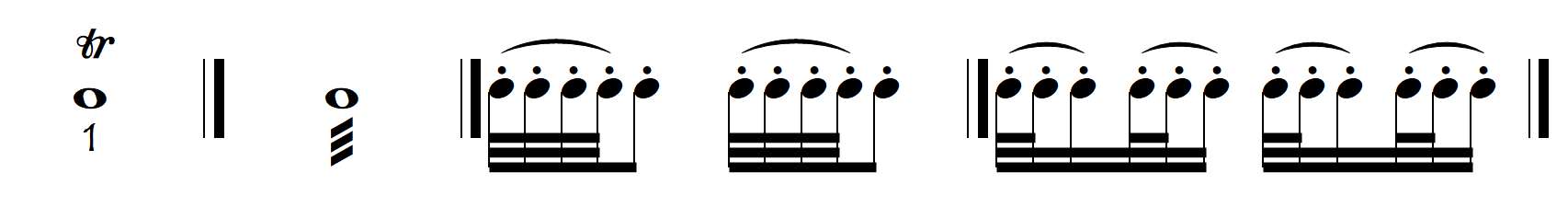

Some of our fastest playing occurs in trills and tremolos, in neither of which, by definition, is the speed notated – we simply play them as fast as we want to (or are able to). Unlike for vehicles, there are no speeding fines for going too fast: we will simply crash. If we set the metronome to 90 bpm and start experimenting with our fastest trills and tremolos we will perhaps find, curiously, that the maximum speed for both seems to be quite similar, at around 8 notes per beat = 720 notes per minute. Because this is quite a high number, and one minute is rather a long time, a more useful speed measure on the cello might be notes-per-second (nps) rather than bpm. Using this measurement, our 720 bpm becomes the easier-to-conceive “12 notes per second”. If we do the same maximum speed test on another type of top speed playing – ricochet bowings – we seem to find a reasonably similar maximum speed, but this speed, unlike for trills and tremolos, cannot be maintained for more than just a few notes at a time.

This maximum obtainable speed will doubtless vary considerably between one person and another and is probably determined physiologically: each body, nervous system, brain etc having its own specific characteristics and some being faster than others. And even for the same person, our non-crash top speed will vary depending on our day, or even on the moment: sometimes we are clumsy and other times we are firing on all cylinders …..

SPEED IS RELATIVE (SO “FAST” DOES NOT ALWAYS MEAN DIFFICULT)

What then is “fast” playing”? Is it always difficult ? What makes it difficult?

In outer space, astronauts are flying around at tens of thousands of kilometres per hour, but because there is no air friction (wind) up there, it feels to them as though they are not moving at all. The same phenomenon occurs when we travel in a large passenger plane: we feel no rushing wind, we are making no effort, the plane is not vibrating and shaking like crazy (hopefully), the earth underneath us is moving very slowly ……. the whole experience is so smooth and easy that we don’t feel that we are moving fast at all.

So the concept of fast has two completely separate components: the objective and the subjective. The objective speed can be measured: in the case of music we could use “notes per minute/second”. The subjective sensation of speed however, could only be measured by physiological measurements that evaluate our emotional (and physical ?) state, because the feeling of speed, is usually just the feeling of difficulty, stress, sensory overload, loss of control.

When we play something fast but effortlessly, it no longer feels fast. For example, play a tremolo …….. now a slurred trill. Easy, no? Our maximum speed, of around 720 notes per minute (= 12 notes per second) is fast but woodpeckers are faster, reaching speeds of up to 20 pecks per second! Of course, machines are faster. Cars cruise at 40 rps and even rest at 15 (idling speed), washing machines spin your clothes at anything from 7 -30 rps, sewing machines sew at 40 -500 and pneumatic drills hammer from 10 – 300 rps. Though 12 notes per second is fast (for any manual activity), the fact that the tremolo or trill is not particularly difficult means that it doesn’t feel fast.

We can achieve these high speeds relatively easily only because the movements involved in each “change to the next note” are very small and are not complex (difficult). On their own, rapid bow changes on the same string, and most slurred rapid finger changes in the same hand position, require very little movement and can usually be considered relatively “easy” (but with plenty of left-hand tongue [finger] twisters as exceptions). Other changes, requiring greater muscular activity (such as large shifts and string crossings), more unnatural movements (tricky finger combinations) or combining several different movements (such as bow change + string change + finger change + shift) are however much more difficult to do quickly.

This is why a more complete evaluation of the difficulty (or trickiness) of a passage would need to combine the simple speed measurement with another measurement that we could call “events per note” or, to be more exact “difficulty-per-note-change”. This measurement would not only count the number of different events (string crossing, new finger articulation, shift, bowchange) that occur between the notes but also evaluate their difficulty. For example, at high speed, a small shift is less difficult than a large one, and a string crossing across one string is easier than a crossing that goes over three strings. In our tremolos and trills, there is only one event per note-change: in the tremolos it is a bowchange and in the trills it is a finger change. When we play our trill with separate bows we double the events-per-note. If we were to give our tremolo a new finger on every note the difficulty skyrockets, and if we add shifts and string crossings then even at 240 npm (a third of the maximum tremolo speed) we are still playing “fast”

While “speed” is measurable, “fast” is thus a totally relative concept, and whether or not a passage can be considered “fast” is not determined by the absolute number of notes played per second nor by the metronome mark, but rather by the amplitude (size) and difficulty (complexity) of the movements involved in relation to the amount of time that we have in which to do them. And because time is relative, what feels like very little time for some people might feel like plenty of time for others. So, in many ways, when we use the word “fast” to describe a passage we are referring more to our subjective feeling of its difficulty rather than its actual speed, as things that feel “fast” for some players will feel simply comfortable for others! What is “too fast” for one player may even be “boring” and “unchallenging” for another. And to add to the subjectivity factor in “fast-playing”, even for the same player what might feel very fast one day may feel much less fast at another moment. Not only are there large variations between different individuals in the speeds of our physiological “computer centre” (brain/body), but also our own processor is greatly affected by our momentary physiological state: tension, tiredness, stress etc can make even a high-performance sports car function like a spluttering old bomb! To look at some of the ways in which we can free up brain-space and make our processor work faster, lopen the following link:

“Tips For Practicing Fast and/or Tricky Passages“

2: WHAT THEN IS “FAST-PLAYING” ?

We talked above about the subjectivity of “fast” playing, but let’s look now some more at the objective, scientific elements of fast playing:

2: 1. INDIVIDUAL, ISOLATED FAST MOVEMENTS

Do you know the “viola joke” about fast playing: A violist claimed that he could play really fast – even semidemiquavers (32nd notes). His colleagues asked him to show them ……. by playing one !

Fast means “with little time”. When we talk about “fast-playing” we are normally referring to passages in which we have a lot of notes to play in a short period of time. But sometimes (very often in fact), even if we have only two notes to play, to get from one note to the next, we have to play one single isolated movement very fast (see examples below). These situations can be considered simply as posing a problem of coordination rather than a problem of “fast-playing”. The best examples of this type of isolated fast movements are given by dotted (or even better, double-dotted) rhythms.

It is interesting and useful to work on these individual fast movements in an isolated way, studying them separately as though we were working with chemicals in a “laboratory”. This is useful because a “fast passage” is simply a succession of many of these small isolated coordination problems, all following each other in a short time. These movements are the basic building blocks of a fast passage. As mentioned above, when there are just a few of these fast movements together, or if they are particularly difficult movements then we will call it a “tricky” passage rather than a “fast” passage.

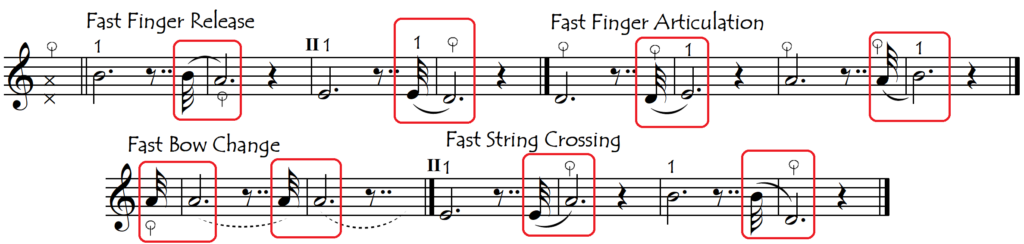

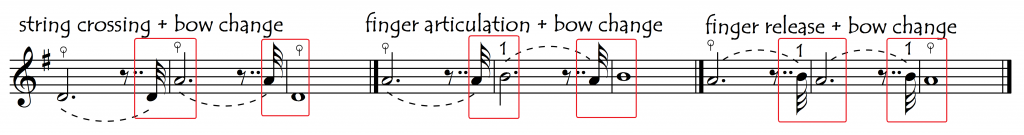

Let’s look at some of these individual fast movements. In the following examples, we have isolated single fast string crossings, finger articulations, finger releases and bow changes:

Be aware that, even though the 32nd note (semidemiquaver) looks fast (because it is so short), the fast movement actually comes after the short note. To prepare for the playing of the short note we in fact have all the time in the world, as we can take time from the long note preceding it. Conversely, even though the note after the semidemiquaver is long, we have very little time to prepare for it. It is this lack of preparation time that makes it “fast”. Fast always refers to the amount of time we have between the notes. This time between the notes is the amount of time we have to prepare the next note and when it is small ….. we have to be fast!

Intelligent fingering will often allow us to place the largest, most difficult movements at those moments when we have the most time to do them, rather than the opposite. In practical terms, this means “shift before the short notes and not after them. See the Technical Fingerings page for more examples:

2:2. COMBINING MOVEMENTS: COORDINATION

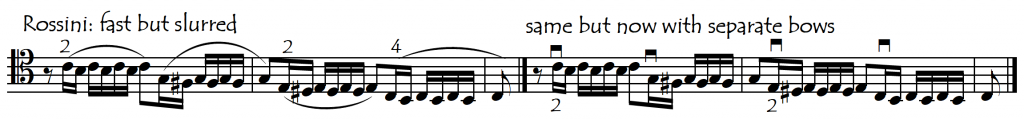

We have seen that “fast” is not necessarily difficult. A change from one note to the next can be anywhere on a scale of difficulty from extremely easy (trill, tremolo) to extremely difficult (large shift + large string crossing + other complications). The “easiest” fast passages, repeat over and over again (rapidly), the same simple movement and don’t pose coordination problems between the two hands. For example, tremolo and trills don’t need much practice because there is nothing really to coordinate: in each case it is only one hand that is “spinning”. But when we start to combine simultaneous changes of different elements in the two hands, we rapidly enter into difficult territory as now we need to perfectly coordinate (synchronise) these changes. It is this coordination that causes us problems rather than simple speed. Let’s try for example doing trill now with a separate bow for each note. Here we are simply combining an easy tremolo with an easy trill, but the sum of these two easy elements gives something indescribably more difficult: a true tongue twister.

This difference between “easy fast” (slurred trill) and “tricky fast” (trill with separate bows) is determined by the need for coordination between the two hands.

In the above example, the notes alternate regularly and predictably: there are no “surprises”. But when the note pattern changes and is not a simple regular alternation then the coordination difficulties increase:

So we can see that the difficulties that occur in fast playing can come from two possible sources:

- the absolute speed of the movements and

- the need to coordinate these different movements

What then are these different movements (“changes”) that have to be synchronised (coordinated)? There are in fact, not many:

- the bow: changes of direction, changes of string (with or without bow change) and bounce-or-not-bounce

- the left hand: changes of note in the same position (finger articulation), change of note to a new position (shifting), change of string (left-hand string crossing)

As we add more fast coordinated changes into our passage we start to increase the difficulty. We have looked at examples of fast repeated identical changes (trill, tremolo) and also at isolated single fast changes (string crossing, finger articulation, finger release and bow direction). Now let’s add to that single rapid note change, one other rapid movement that has to coincide exactly with the note change. Now we are entering into the world of “coordination”:

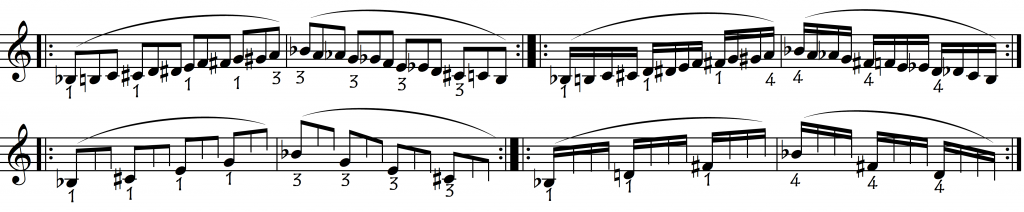

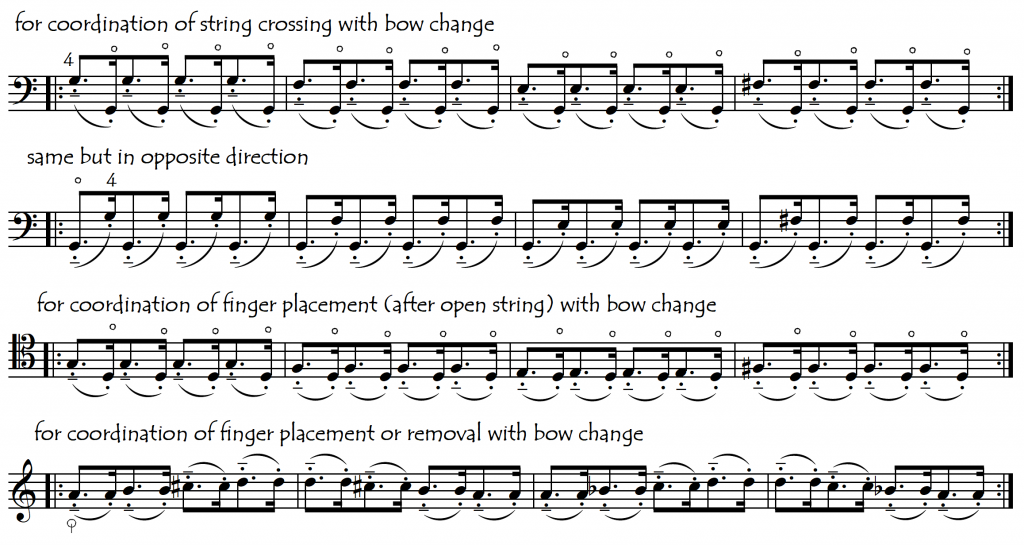

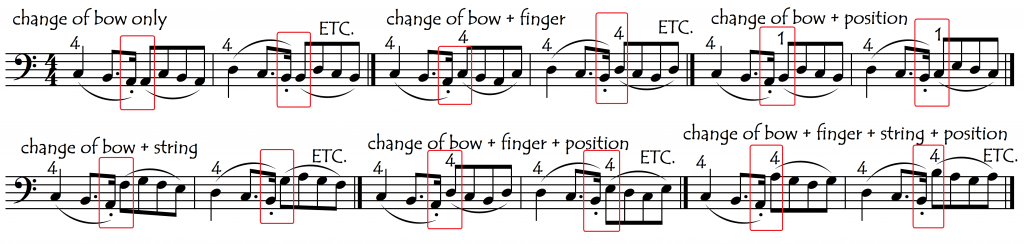

For our most basic practice of speed and coordination, we can usefully work on each of these different coordination skills separately and individually, inventing our own little exercises or studies, specialised exclusively in each movement. When playing the first two lines, keep the lefthand finger always down (don’t rearticulate it each time the bow plays it):

We can then add a third movement to that single note change, for example, “string crossing + bow change + new finger articulation”. Or we can even have four movements required for a single note change as would happen if we added a shift to the preceding example (string crossing + bow change + finger change + shift). Look at the following progression:

- in the first example, we have no other movement to coordinate with the bow change

- in the second, third and fourth examples, we need to coordinate one other movement with the bow change

- in the fifth example, we have to coordinate two other movements (change of finger and position) simultaneously with the bow change

- in the sixth example, we have to coordinate three other movements (change of finger, position and string) with the bow change

To increase the difficulty even more we could:

- make the string crossing a leap over 2 (or 3) strings and

- make the shift larger.

2.3 ANTICIPATION AS AN AID TO COORDINATION AND THEREFORE TO FAST PLAYING

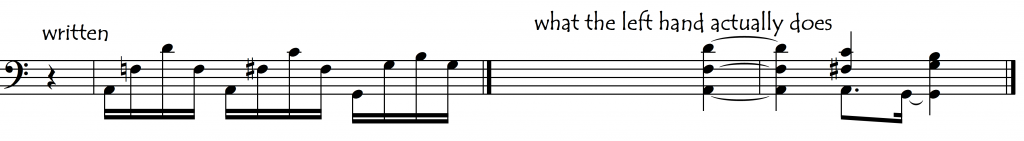

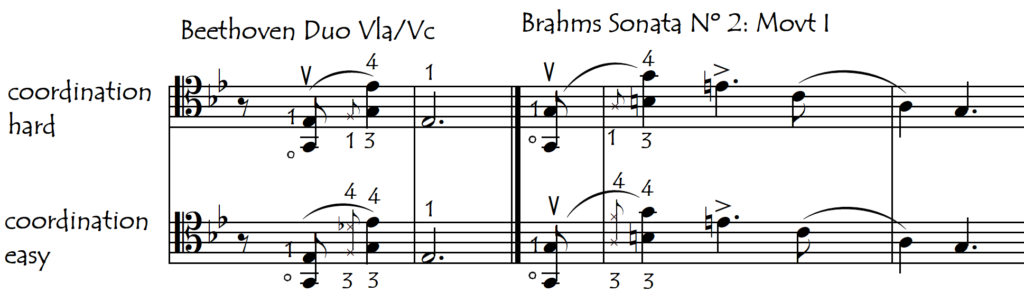

Very often we can prepare movements before they are actually musically (rhythmically) required, and by so doing, we separate movements into a consecutive chain that would otherwise need to be performed simultaneously. This anticipation thus eliminates potentially problematic coordination difficulties. In the following example, absolutely all of the left-hand articulations are anticipated (prepared). None of them coincide with the bow change/string crossing. If we try to articulate each finger at exactly its required moment, we will see how it becomes impossible to play the passage quickly.

In chords that contain shifts (or simply in shifting doublestops with a change of string), we have the potential difficulty of coordinating three different movements (the articulation of the new finger, the arrival of the hand in the new position, and the arrival of the bow on the new string) all at the exact same metronomic moment. This is quite difficult (try it) and is a very good exercise in timing, coordination and fine motor control. But it is an unnecessary difficulty, especially in a musical context.

To avoid this coordination problem we can anticipate the placement of the new finger on the new string. In this way, our bow’s change of string doesn’t need to coincide exactly with the rhythm but can be made anticipatedly. This “anticipated” string change not only integrates itself perfectly into the music but even improves our playing because it allows our lefthand glissando to be heard on both strings.

Fast and/or tricky passages can often be helped enormously by anticipating as many of the movements as possible. See the section in Basic Technique dedicated to the subject of Anticipation

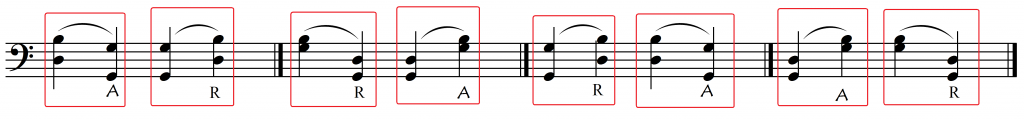

Sometimes however we have no choice and must coordinate the movements simultaneously. This is when things start to get difficult and innate sporting talent (good fast timing and coordination) really helps. In the following example, we need to coordinate perfectly the slurred string crossing with a finger articulation (A) or a finger release (R). Even at slow speeds, this is not easy! Note that the first finger on the A string doesn’t move at all in the following example – it stays stopped throughout.

The more empty space (time) we have between the note changes, the easier our coordination problems become because that time (space) allows us to do all the necessary movements before we need to play the new note(s). If the above pairs of notes were not slurred, then everything would become easier, and if there were actual rests between the notes then the coordination difficulties would basically disappear.

Another way to reduce the coordination difficulty is to play in a jazz/pop/folk mode, with (very small) left-hand glissandi rather than precise, pianistic, bang-on-time finger articulations/releases.

In this way, only the bow’s string crossings pose a timing/coordination problem. For the left-hand, while we do want to arrive at the “new” note exactly “on time”, the fact that we slide into it without a precise moment of finger articulation/release gives us a lot more time to “get our act together” as well as giving us a whole lot of aural feedback (the glissando) to help with the accurate timing of our arrival at the target note. The addition of even only very small (semitone) glissandi down from and up to the fourth finger has the effect of greatly reducing the complexity of this double-coordination of the string crossing with the finger change. This “blurring” of what would otherwise be precisely timed finger articulations and releases is a technique we can use not only to overcome/eliminate coordination problems but also to give our playing a nice, loose, laid-back, relaxed feel when we play jazz, pop and folk music or any music of the more popular music styles.

But this technique is not only useful in popular music:

The left-hand’s gradual glissando into a new note (or notes) is exactly like the right-hand’s gradual approach to a new string apart from the fact that we can’t hear the approach of the bow to the new string. If only we could !

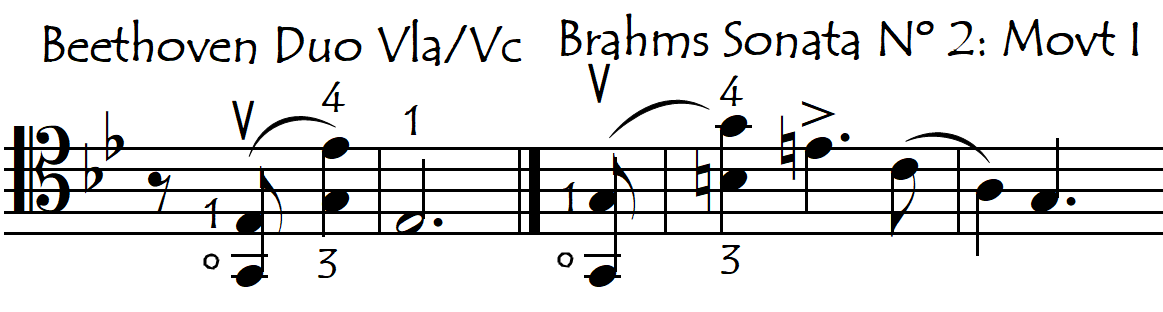

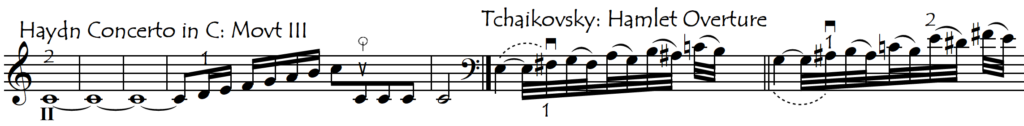

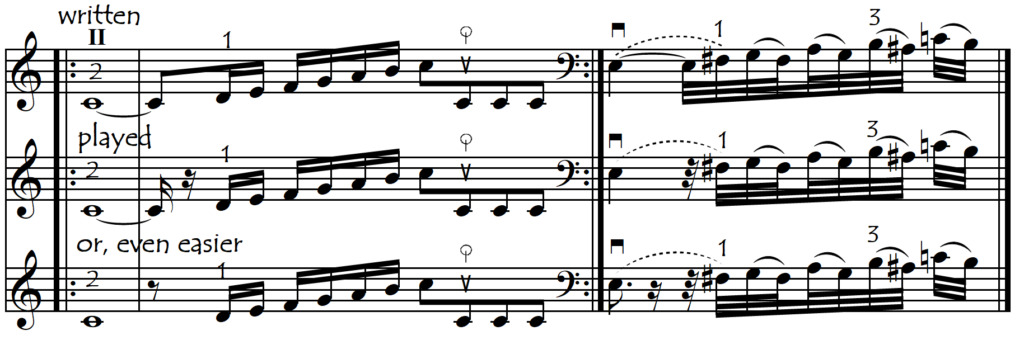

CONTROL OR OVERCONTROL: SEIZING UP

Seizing up – getting blocked – in fast passages, is often a sign that we are trying to play individually every little note. How can we fix this? When playing rapidly, we mustn’t try to think about consciously playing each note as a separate entity – there is simply not enough time. We just need to have a few control points situated along the way, while for the rest of the notes, we simply let the hand do its work peacefully and automatically, as shown in the second line of the following example. Fast chromatic scales provide good study material for this subject because, although we are moving rapidly, we are not moving large distances. Therefore, chromatic scales are more of a brain problem than a real physical difficulty.

Another example of the difference between overcontrol and healthy control, taken this time from the world of psychology: compare the positive effects of the healthy interest of a parent (or partner) in supporting what their loved ones are doing, with the negative effects of the overbearing, suffocating, “interest” of a parent/spouse who wants to control every detail of their loved one’s life!!

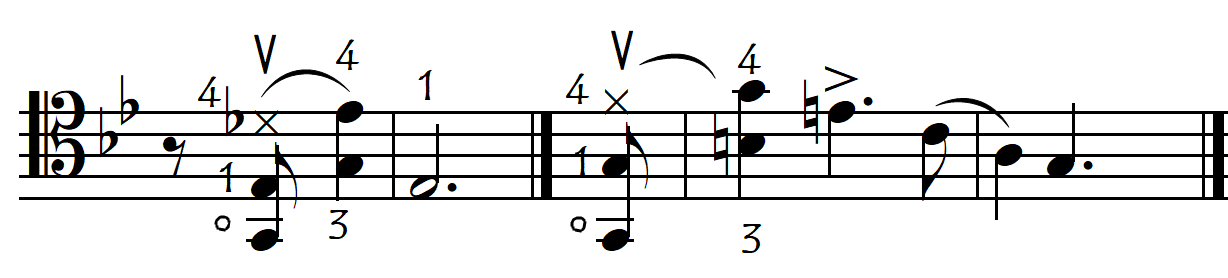

And now, coming back to cello technique, another example to illustrate this phenomenon. Try playing a chromatic scale once again, but this time using only one finger.

If we try to play this above example “carefully and exactly” (with one movement for each note) it will be an almost impossible exercise in coordination and will drive us quite crazy! However, if we do it with a smooth, relaxed, totally loose glissando it’s as easy as pie! And the intonation is no problem if we use a few control points on the way up and down as shown on the second line. Try it on any finger – even on the thumb!

If we try to play this above example “carefully and exactly” (with one movement for each note) it will be an almost impossible exercise in coordination and will drive us quite crazy! However, if we do it with a smooth, relaxed, totally loose glissando it’s as easy as pie! And the intonation is no problem if we use a few control points on the way up and down as shown on the second line. Try it on any finger – even on the thumb!

We have a whole separate page dedicated to this important subject. Click on the following link for a more detailed discussion:

RUSHING

The biggest problem with fast and tricky passages is our natural tendency to play them too fast. Either we start too fast from the very beginning, or we accelerate during the passage (or both). This is Rushing, a very unwanted and dangerous – but totally natural – phenomenon to which we have dedicated a page of its own.

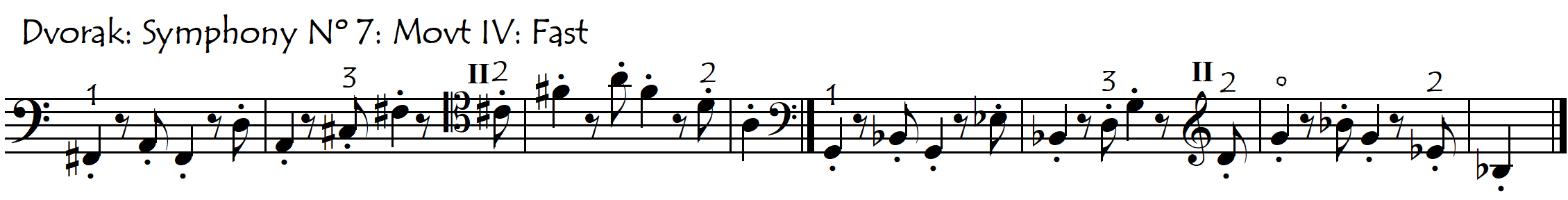

FAST AND SOFT: THE MOST DIFFICULT

The combination of fast and soft is a curious (and difficult) one. We generally associate “soft” with the concepts of “gentle”, “tender”, “relaxed”, “sleepy” and even “slow”, so playing fast and soft simultaneously can feel a little contradictory. It’s a little like whispering when very angry, or running a 100m sprint on the tips of your toes: it just doesn’t feel “natural”. The energy, speed and articulation needed for fast playing are more easily applied and controlled when we play louder. Try the following passages, both loudly and softly and you will see this.

This contradiction is most pronounced for the Left Hand. The cello is quite a large instrument and its strings are not only thick and long but also quite high above the fingerboard. Because of these properties, compared to many other instruments the cello needs quite a strong and energetic articulation of the left-hand fingers in order for the notes to speak, even in pianissimo playing. To play softly, we automatically reduce the pressure of the bow on the string. But if we simultaneously reduce the energy level of the left hand in parallel with this reduction in bow pressure, we are likely to lose the clarity of the articulation of each individual note in our fast soft passages. With the exception of Thumb Position (where the thumb is holding the string down to the fingerboard), the cellist’s left-hand fingers can’t really just race lightly over the notes. In fact, when playing softly and fast, the left-hand needs to articulate with almost the same energy and speed as if we were playing loudly. This is especially so in slurred passages because in a slur, the bow cannot help with the articulation of each new note. Thus we basically have to “uncoordinate” the energy levels of the left and right hands in fast soft playing. This is like those amusing coordination party tricks such as rubbing circles on our tummy while tapping our head, or doing clockwise circles with our right foot while drawing a 6 in the air with our right hand: it doesn’t come naturally ………….. and thus requires practice.

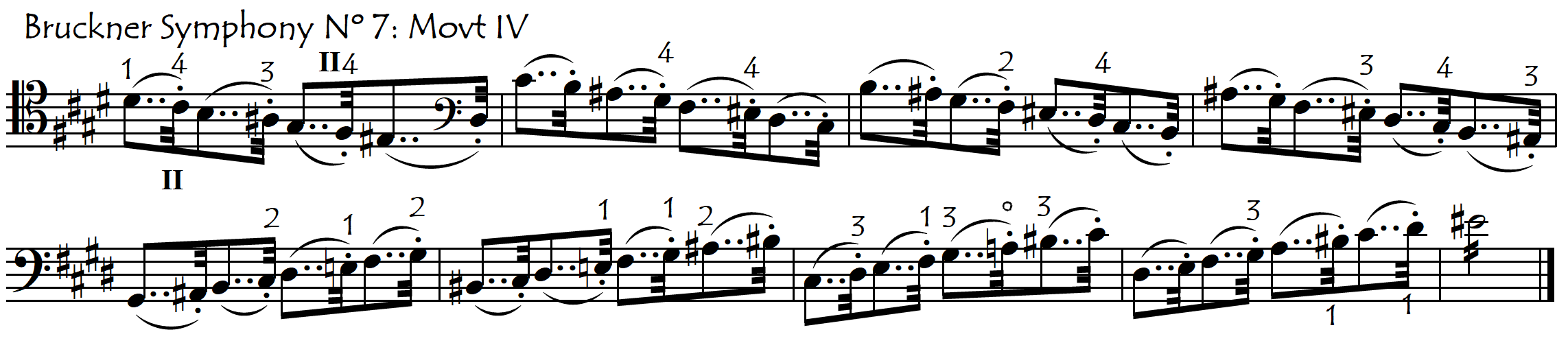

Curiously, as with the above examples, it is in orchestral repertoire that we will most often need this skill.

COORDINATION AIDS: THE BEAT, THE DOWN BOW AND ACCENTS

The significance of the beat, the down bow and accents, as coordination aids in fast passages is another large subject which has its own page here:

Coordination Aids: The Beat, Accents, Downbows etc

SPICCATO

We have mentioned how the difficulty of a “fast passage” is the sum of all the individual rapid movements that have to be coordinated together. But when we have to do all these rapid movements while maintaining a bouncing bow we are no longer talking about a simple addition but rather about a multiplication of the difficulties of playing fast. See the Spiccato page

QUICK WAKE-UPS

Imagine this situation: we know that we will have to leap out of bed and perform some high-speed tasks at 8.00 AM. We have a choice: either we stay deeply asleep till 7.59.59 when the alarm goes off, or we wake ourselves up a little earlier in order to prepare ourselves for the sudden radical change in activity level. This same situation occurs regularly in music: we need to take off suddenly at top speed after a long note (or silence).

How do we prepare then for these sudden high-speed departures? Simply by not “going to sleep” during the long note (or rest)! If we make the effort during the long note to imagine the driving inner pulse of those fast little notes that we will soon need to play, then we should have no problem. It’s a little like relay racers: in order to take the baton from the previous runner with a smooth and fluid transition, they need to be already running at the same speed. As a practice method, we can actually play these smaller subdivisions instead of just playing the long note: this helps to get our brain used to imagining those smaller note values even when we are not actually playing them:

It helps to remind ourselves that the shift after the long note is NOT fast !! We can shorten the long note before the fast getaway without anybody noticing:

TYPES OF FAST PASSAGES: A HIERARCHY OF DIFFICULTY

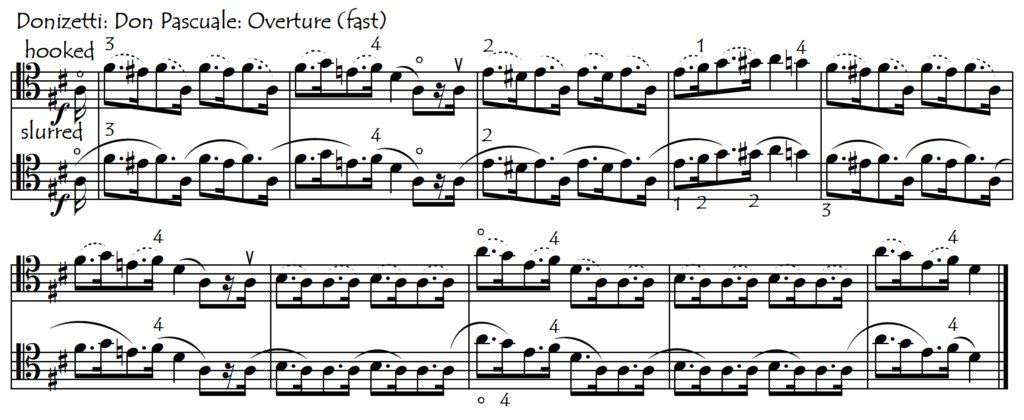

In the same way that we can decompose any fast passage into its different components, we can classify fast repertoire passages according to the types of problems that they contain. In this way, we can create a sort of approximate “hierarchy of difficulty” that might allow us to work on our fast playing in a more progressive and structured way. Some fast passages (especially slurred ones) are almost exclusively problematic for the left-hand. Others might pose almost exclusively right-hand problems. In fast hooked-bowing dotted passages, for example, the sensation of speed and difficulty comes from the problems of the right hand in articulating the dots. If played slurred, they no longer feel fast or difficult:

But the majority of passages that we consider “fast” involve coordination problems between the two hands. By practising any fast passage with a variety of bowings: slurred, separate (including spiccato) and mixed we not only integrate the passage better into our brain and hands but also improve our general fast coordination skills between the two hands. The following link takes us to compilations of repertoire examples and exercises for each different “category”.