Bach: Cello Suites: Violin Fingerings, Thumbposition, Extensions and Cello Size.

VIOLIN FINGERINGS AND THE USE OF LOW-REGISTER THUMBPOSITION IN THE BACH SUITES

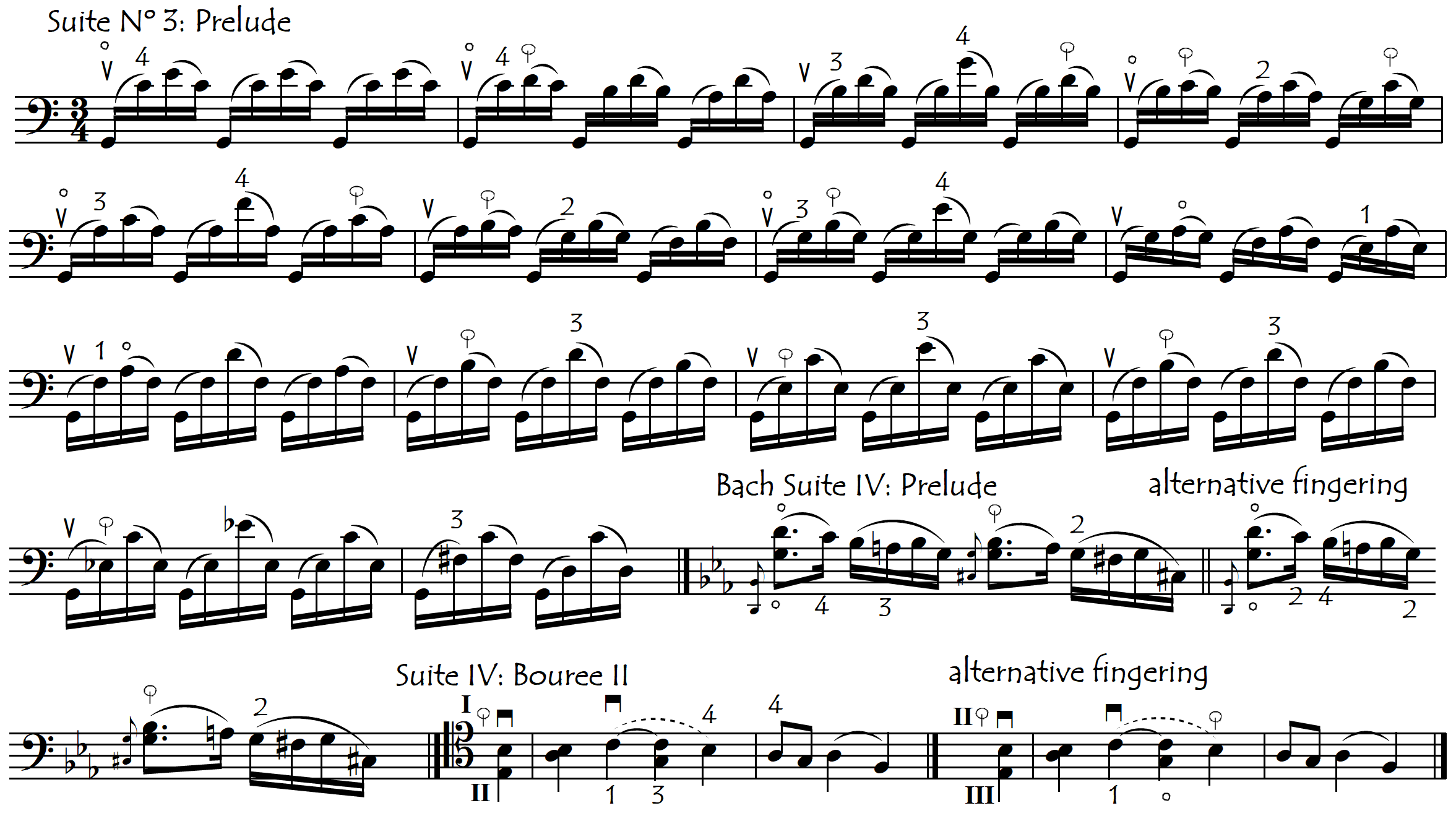

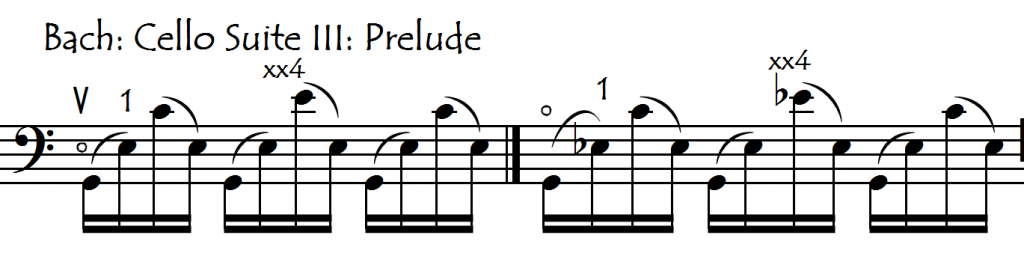

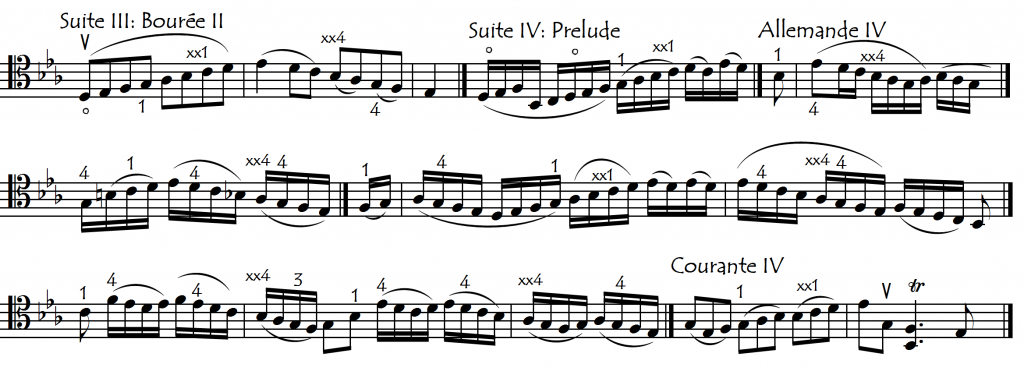

Even though the Bach Cello Suites normally stay in the Neck Region, certain passages in the Cello Suites are impossible to play without using thumbposition because of the extensions required. Here are just a few of those passages (a link to an entire compilation can be found just below):

This need for the thumb in Bach’s music is strange because thumbposition was as yet almost certainly unknown to him and his cellists. Even for thumposition’s first inventors (see “History Of Thumbposition“) it was only ever used as a way to play “up high”, never in the Neck Region. These passages lead us to believe that the Suites were almost certainly composed for a smaller instrument, on which violin fingerings could be used (see the following article). The following link opens a compilation of passages in the Bach Cello Suites for which we could, should or must, use the thumb. The Sixth Suite is included here but only as played on a 5-string cello or transposed down a fifth:

Thumbposition Passages In The Bach Cello Suites

Violin fingerings (with a handframe of a perfect fourth) are often impossible on the modern cello without the use of the thumb, but while the thumb is often our salvation for these passages that were conceived for violin fingerings, there are other passages for which even the thumb cannot save us and we need to rewrite the music (notes) in some very minor ways:

The following link opens a compilation of all the “violin-fingering-conceived” passages in the Bach Cello Suites for which we need either to use the thumb or rewrite the music (or both) in order to be able to play them successfully. These passages seem to show without a doubt that Bach imagined his cello suites to be played with violin-type fingerings.

Bach’s Use Of Violin Fingerings In The Cello Suites: EXAMPLES

NORMAL 1-2 TONE EXTENSIONS IN THE BACH SUITES

Above, we have looked at the “impossible” extensions. Now let’s look at the frequency of the “normal” 1-2 tone extensions in the different Suites. For large-handed cellists, this is completely irrelevant, but for small-handed cellists it is quite interesting (see Extensions and Hand Size). Of course, the frequency of extensions in any piece can vary widely according to our choice of fingerings. Let’s look at the Courante of Suite IV, for example. We can finger it in such a way as to avoid as much as possible the use of extensions (leaving us with only 16 unavoidable ones) or we can do the absolute opposite and finger it with a maximum of extensions (which gives us approximately 100 of them), thus converting it into a study for the use of extensions. To look at these different fingering styles, open the following links:

Courante Suite IV: Fingered With A Maximum Number Of Extensions

Courante Suite IV: Fingered With A Minimum Of Extensions

For the following table, the number of extensions in each movement has been counted using fairly standard fingerings. The Courante of Suite IV, with “standard” fingerings has 56 extensions – approximately halfway between the two extremes of fingering that we have just looked at.

The “Galanterie” movements refer to the pairs of Minuets (Suites I and II), Bourées (Suites II and IV) and Gavottes (Suites V and VI) found always between the Sarabandes and the Gigues.

|

FREQUENCY OF “UNAVOIDABLE” 1-2 TONE EXTENSIONS IN THE BACH CELLO SUITES |

||||||||

| Prelude | Allemande | Courante | Sarabande | Galanterie1 | Galanterie2 |

Gigue | TOTAL | |

|

Suite I |

6 |

8 |

17 |

5 |

5 |

15 |

7 |

63 |

|

Suite II |

50 |

31 |

22 |

7 |

13 |

6 |

29 |

158 |

|

Suite III |

36 |

18 |

44 |

7 |

5 |

9 |

13 |

142 |

|

Suite IV |

137 |

71 |

56 |

17 |

46 |

18 |

101 |

446 |

|

Suite V A=A |

19 + 128 |

19 |

10 |

12 |

26 |

9 |

19 |

242 |

|

Suite V A=G |

13 + 100 |

17 |

11 |

12 |

30 |

7 |

20 |

210 |

|

Suite VI in G |

93 |

15 |

21 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

23 |

163 |

We can see from this table how, suddenly in the Fourth Suite, with the key of Eb major, the number of necessary extensions explodes. There are (many) more extensions in this Suite than in the three preceding Suites combined! This Suite is hard physical work, especially for a small left hand.

DOUBLE-EXTENSIONS IN THE BACH SUITES

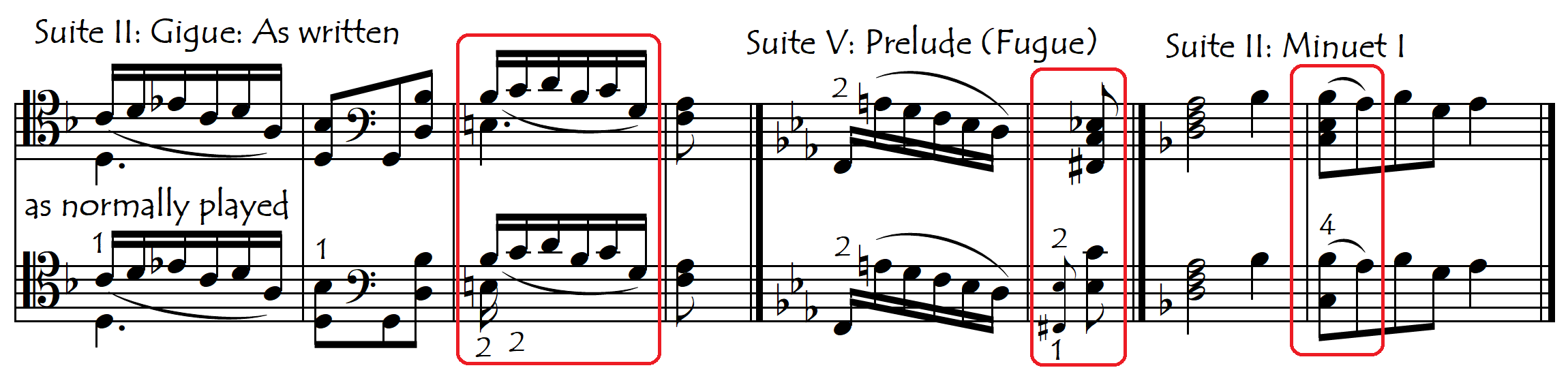

But it is not just the use of simple single extensions (with one tone between the first and second fingers) that explodes in the Fourth Suite, but also the need for double-extensions (a perfect fourth between the first and fourth fingers). In Suites I and II we have no need for any double-extensions. In the C-major movements of Suite III there are only two moments where most cellists will use a double-extension (these can however also be avoided by using the thumb).

In the second Bourée of Suite III (in C minor), and in the Eb major key of Suite IV however, if we want to avoid using “romantic” fingerings (climbing up to the Eb on the D-string), then we will need to do frequent double-extensions, all due to the presence of Ab, as in the following examples:

Of course, we can avoid these double-extensions by fingering these passages up and down the D string rather than crossing over to the A string, but it is highly unlikely that Bach’s cellists would have done this. Bach only ever took the cellist’s left hand out of the Neck Region once, for a brief moment in the Sixth Suite. All his other “high” cello writing is for the Viola da Gamba or the Violoncello Piccolo.

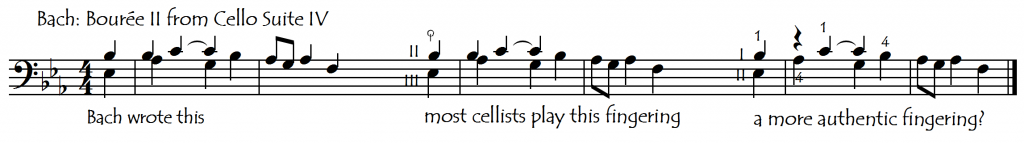

The Fourth Suite, more often than any other, shows either that the cello was smaller than now, or that Bach didn’t quite understand the limitations of reach of the cellist’s left hand. According to Bach’s writing, it would appear that cellists of his day could comfortably reach a perfect 4th, as shown in the above examples and also in the following example from Bourrée II of the Fourth Suite. Most modern cellists play this passage in thumbposition on the D and G strings, but we can be absolutely sure that no cellist of Bach’s time would have done this as Bach’s cellists didn’t use the thumb ever. See History of the Thumb Position

CONCLUSION

Could it be that Bach overestimated the extension possibilities – both simple and double – of the cellists left hand in this Suite? Could it be that Bach even decided to use the scordatura in his Fifth Suite to avoid repeating the same ugly sounds and out-of-tune playing that this key signature with three flats caused (and continues to cause) his cellists in the Fourth Suite? Or is the explanation for all these difficult (or impossible) extensions the fact that Bach wrote these Suites for a smaller instrument that could be played with violin fingerings (see the following article)?

We can avoid some – many even – extensions by looking for special fingerings (see Fingerings to Avoid Extensions) but many are unavoidable. Often our bowings need to be decided in accordance with our fingerings (and vice versa). There is no point playing a legato slur with the bow in a passage in which the left hand cannot play legato (because it has to do an awkward shift or stretch). The bow’s slur will only make the passage sound ugly because it doesn’t allow us to discreetly place the uncomfortable movement in that millisecond of time (and silence) that a bow change gives us (see Choosing Bowings).