Reverse Bowings For Cellists

“Reverse” bowings refer to those bowings in which the beats, pulses, or accented notes are played on the upbow. Although we won’t be talking much about them here, there are many reasons why it feels most natural for string players to have the pulse (the accented beat) on the down bow, especially when we are playing many fast “small” notes.

It would seem that when the two bowing symbols that we use to indicate up and downbows first appeared, they were derived from the latin words “nobilis” (noble) and “vilis” (weak, unimportant). French renaissance composers liked to write an “n” above important notes, indicating that they were to be played in a particularly beautiful, noble fashion. To the players, this was generally a prompt to play those notes from the frog (downbow). A “v” above a note meant the opposite, indicating that these notes didn’t need much attention. These notes were thus used as an opportunity to bring the bow back towards the frog (upbow).

The “n” and “v” letters thus evolved into our present-day bowing signs. It is not surprising that these symbols originated in France, because they are only valid with the “french” (overhand) bowhold. With the german (underhand) bowhold, standard then and now for the viola da gamba, it is/was the upbow that is the stronger stroke while the downbow is the weaker return stroke. Nor is it surprising that these symbols evolved in the Renaissance/Baroque period because with the primitive bow, the difference between up and down bows was much greater than since the invention of the Tourte bow at the end of the 18th century.

Getting comfortable with “reverse bowings” is a surprisingly useful skill because these bowings are not only often unavoidable, but also are sometimes our bowings of choice to get us out of some tricky situations. Developing this skill is a little like developing the ability to be ambidextrous (being able to use both hands equally well). It’s as though we were learning to write with our “other” hand, with the difference that we will need our reverse bowing technique much more often than we will ever need to write with that “other” hand! Let’s look now at some of the different situations in which we will use reverse bowings, either by choice or obligation:

UNAVOIDABLE REVERSE BOWINGS

TRIPLETS AND COMPOUND TIME

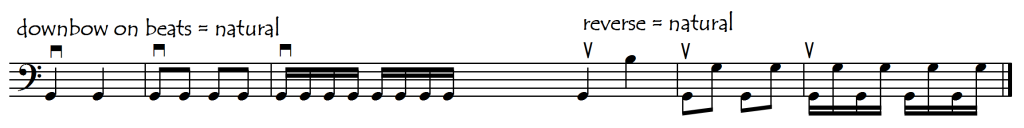

The most obvious of these situations are found in triplet rhythms or compound time (3/8, 6/8, 9/8, 12/8). Here, for separate-bow passages, every second triplet figure will start with the “reverse” bowing, with an upbow on the beat. This bowing “irregularity” – having every second beat starting on an up bow – makes it easier to get “tangled up” because we are normally so accustomed to playing with down bows on the beats.

3/8 and 9/8 passages are of course the worst as they “compound” (multiply) the difficulties. In these time signatures we don’t only have to manage groups of three notes (triplets), but we also have to group them in threes! This means that every second bar begins on an up bow and even a repeated bar will have the reverse bowing the second time.

For this reason, triplets and compound time passages are an excellent entry-level introduction to the problem of “reverse-beat-bowings” as well as constituting an added difficulty in fast/tricky passages.

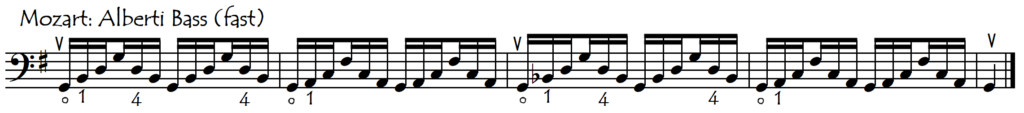

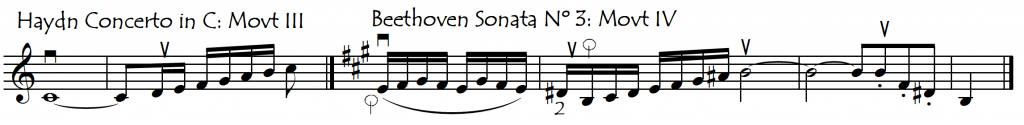

The above Haydn excerpt is relatively slow, which makes the coordination problems much easier. For working on our faster coordination, if we can keep the lefthand simple, with fewer note changes, it will help us to focus on the bow. Placing a little accent on each beat (giving an alternation of down and upbow accents) will often help our coordination.

CHOOSING REVERSE BOWINGS FOR STRING CROSSING PASSAGES

In string crossing passages, the bow has a very strong natural preference to go to the lower string(s) on the downbow and to the higher string(s) on the upbow. Click here to go to the article dedicated to this subject. This mechanical preference for having the downbows on the higher string (and upbows on the lower) will often override our rhythmic preference for having the downbow on the beat, which means we will often play string crossing passages with “reverse” bowings.

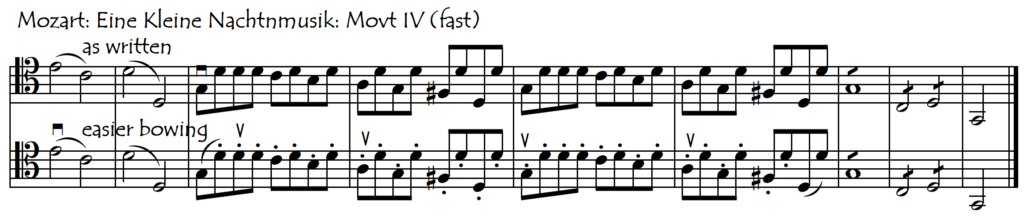

If the string crossings are spiccato, we will have even more reason to want to play the crossings in the “favourable” direction as this not only helps the crossings but also the bounce. Sometimes this this might require adding a slur to get into the reverse bowing and/or to get back to “normal direction” bowing:

CHOOSING REVERSE BOWINGS IN ORDER TO BE IN THE RIGHT PART OF THE BOW

Rapid separate-bow-passages are easier in the upper half of the bow. We may prefer to play them with a reverse bowing out there in the “easy part of the bow” rather than with a non-reverse bowing in the scrubbing region (lower half).

In the above example, we deliberately chose our bowings in such a way as to give ourselves reverse bowings. We can also do the opposite – choosing our bowings to avoid these reverse passages.

UPBOW UPBEAT FOLLOWED BY DOWNBOW DOWNBEAT ? NOT ALWAYS !!

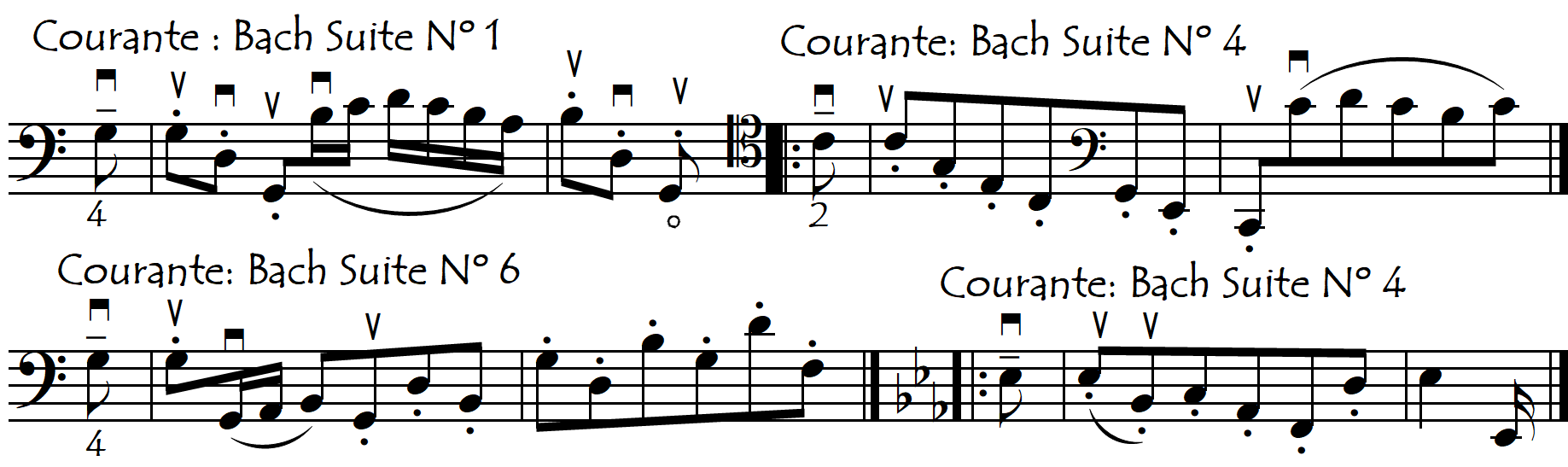

It would seem that, even linguistically, upbows are made for upbeats and downbows are made for downbeats. But while an upbow upbeat followed by a downbow downbeat, is certainly a very common figure, sometimes we can do exactly the opposite. For example, in the Courantes of most of the Bach Suites:

HOOKING TO AVOID REVERSE BOWINGS

In Minuets, Waltzes and other music in ternary time, when the articulation and speed are favourable, we often just play “down-up-up” (the equivalent of the typical Oom-Pah-Pah figure on the tuba), hooking together the two last notes on two up bows instead of doing a reverse bowing on every second triplet figure. But this bowing is not always possible or desirable, especially at faster speeds. Play the following example at a constant metronome speed. Above a certain speed, the two hooked upbows are no longer practical and we will need to do the as-it-comes bowing with every second triplet figure using the “reverse” bowing. See also the page dedicated to “Hooked Bowings“.

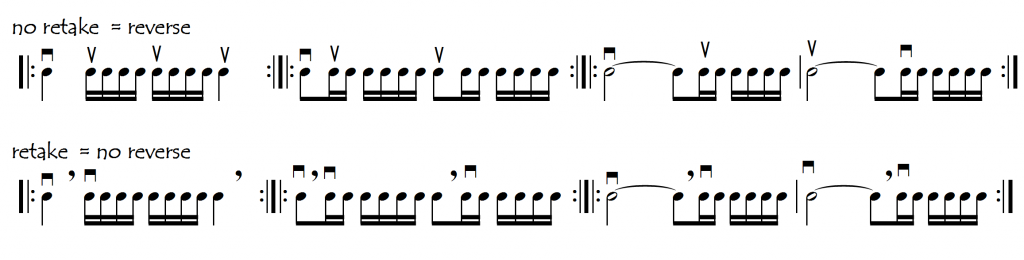

RETAKING TO AVOID REVERSE BOWINGS

It is not only in ternary and composite rhythms that reverse bowings appear. In many passages in “binary” rhythms, we will find groups of notes in which the normal backwards-and-forwards alternation of bow directions produces figures with reverse bowings. Sometimes we can retake to avoid that. See also the page dedicated to “The Retake“.

HOW TO DEVELOP REVERSE BOWING SKILL

Passages in separately-bowed triplets make the alternation of down and upbows on the beat very obvious and predictable but in any complex bowing passage we are likely to find up bows on the beats or requiring accents. Therefore, deliberately practicing “reverse” bowings in non-triplet passages, is a very useful exercise in coordination that will help us enormously in our playing of fast complex passages. Developing this skill is a little like developing the ability to be ambidextrous (being able to use both hands equally well). It’s as though we were learning to write with our “other” hand, with the difference that we will need our reverse bowing technique much more often than we will need to write with that “other” hand!

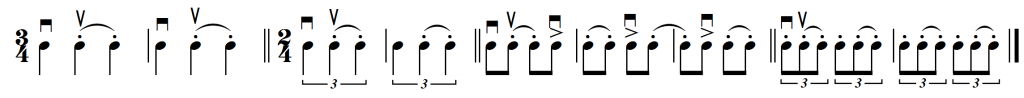

To develop this skill progressively and logically, take any study or extended passage in continuous quavers (8th notes) and play it in the following ways (in order of difficulty):

1: Play two semiquavers on each note (or, to make it even easier, four). Play with down bows on the beat

2: Do the same but in 6/8 with three bow strokes now on each note

3. Play this triplet rhythm with a 9/8 pulse

4. Do the 6/8 version (nº 2), but starting each bar on an upbow

5: Now do the first exercise (binary semiquavers), but this time playing with the upbow on the beat

The following example illustrates this progression of difficulty:

An alternative rhythmic progression that can be used on any sequence of notes (scales are probably the easiest) is offered here below:

Soft, gentle tremolos with imperceptible starts, such as those that begin most Bruckner symphonies, sound better (less defined) when we start them on upbows. Playing tremolos in this manner also helps us to get used to reverse bowings. Gentle ends to tremolos are also much better on upbows. In fact, almost all gentle starts are better on upbows, independently as to where the “beat” might be.

The following links open some compilations of repertoire excerpts in which we will need these “reverse beat” bowings:

Fast Separate-Bow Triplets With Three Bowstrokes On Each Pitch: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

Fast Separate-Bow Triplets With One Bowstroke On Each Pitch: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

Bowing “Against” The Beat (not triplets): REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

The Courante from Bach’s First Suite is full of reverse bowings and makes an excellent study for this skill. Here it is, bowed in such a way as to use an absolute maximum of reverse bowings:

Courante From Bach’s First Suite Bowed Especially As Study In Reverse Bowings