Bach: Unaccompanied Violin Sonata Nº 3 BWV 1005: Transcribed For Cello

The source for this transcription is Bach’s autographed manuscript. In the “Literal Transcription” this manuscript has simply been copied and transposed down a fifth (plus an octave). All the bowings in the “Literal Transcriptions” are Bach’s. In the “Edited Concert Versions” however, Bach’s bowings have very often been changed.

MOVT I: Adagio

This is not an easy movement on the cello and we might have many questions about how to play it, both technically and interpretatively. One of the main difficulties comes from the fact that it is almost constantly in doublestops and chords. Of its 141 quarter-note beats, no less than 121 (more than 85%) have at least one doublestop or chord on them. In fact, 85% of all the notes in this movement are part of either a doublestop or a chord. In spite of this densely chordal nature, surprisingly only six chords have needed to be revoiced to make them possible for the cello (in bars 9, 22, 24 and 33).

Because of the lack of harmonic clarity in doublestops in our low register, it may be a good idea to experiment with playing only the bottom note of some of the spread four-part chords, playing the G-string note only in passing on the way to the top strings. For the same reason, the three low “F’s” in bar 2 of our solo version have been taken up an octave to get them out of the hippopotamus register. Bach’s original jumps an octave in the next bar anyway so we have just advanced that jump by one bar. In all of the spread chords, the grace notes which start the spread should be played before the beat.

In bar 18, many violinists spread the three chords downwards (starting from the highest notes of the chords). Although it does definitely make the voice leading in the bass line very clear, this sounds suddenly very strange, coming as it does in a piece in which the other 79 chords are all spread from below. Chords would never be spread downwards on any instrument on which the bass note continues ringing on (lute, guitar, keyboard with pedal etc) and we have decided to spread these chords from the bottom up, hoping that our ears are able to remember the bass note of the chord and make the voice leading connection.

It is hard to know how much (and when) we should play legato in this movement. Certainly, bars 34-35 and the slurred pairs of 8th notes in bars 5, 7 and 9 will be legato but Bach’s use of slurs in the 89 dotted rhythm figures is inconsistent, with slurs over 30 of them but no slurs over the other 59. Violinists tend to play this movement very legato (baroque violinists much less) but we cellists might prefer to have a little relaxation before many of the short notes of the dotted figures to allow us to relax the hand, shift and/or prepare the string crossing for the following broken chord. In other words, instead of a truly legato slur, in many figures we may prefer to do a gentle portato, hooked bowing. We have tried to indicate this difference in the Edited Version through the use of solid and dotted slur markings but many other choices of portato and legato are possible. Possibly it would have been better to do as Bach did, leaving many bars without any bowing indication.

It is also hard to know how much to maintain the doublestops, maintaining both voices in the doublestops or shortening the non-melodic voice to allow for greater transparency of texture (and a more relaxed left hand). Bach, as always, writes all of the doublestops with the full duration of their harmonic relevance but this never means that both voices must be held for their full rhythmic duration.

With such gentle, peaceful music it is very tempting – but probably “wrong” – to play the dotted figures as triplets (2+1) rather than as the 3+1 rhythm that Bach wrote. One wonders why Bach didn’t use a triplet 9/8 rhythm: perhaps this movement is not as peaceful and tranquil as we thought ? Or perhaps it was to keep the speed very slow: triplets tend to flow along faster while quadruplet dots (at slower speeds) suit a more poised, hesitant, reflective delivery ?

Apart from the chords and doublestops, probably the greatest difficulty of adapting this Adagio to cello is actually its very low register, the highest note being only an Eb on the A-string. This low register, combined with the constant double-stopping and chords makes it a prime candidate for playing as a cello duo, transposed up a fifth (into the original violin key). It really does sound a lot better in this way, played in the original key by two cellos rather than transposed down a fifth for one solo cello. But even after distributing all the notes between two cellos, there is still the need for frequent double and triple-stopping. Because of this, it is actually the three-cello version that gives the best results: now all the harmonies can be played completely free of all tension. One wonders why Bach didn’t just write this piece for string orchestra from the beginning! No additional notes have been added to these duo and trio versions apart from an optional harmonisation of bars 12 and 45-46.

MOVT II: Fugue

This is a colossal work. It is the longest of Bach’s solo violin fugues, and like the others, is intensely polyphonic, with a total of 338 doublestops and 250 chords. Because each chord is composed of two doublestops, this gives us a grand total of 344 + (250 x 2) = 844 doublestops!! Even when we divide the notes of the polyphonic passages between two players (in the “Duo Versions”) we still sometimes have too many notes to play. To be really comfortable, we would need to make a version for three cellos, but then the third cellist might go to sleep in those many non-polyphonic passages where there is nothing for them to do!

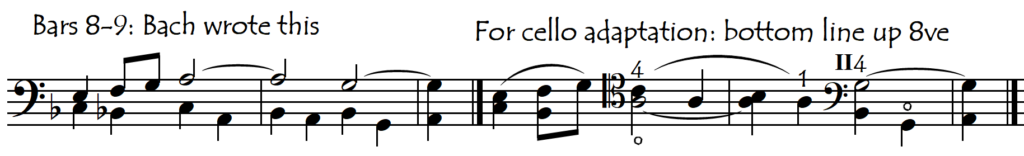

In the “solo” version, many chords have needed to be revoiced to adapt them to the cello. When deciding whether or not to eliminate or change a note in a chord, priority has always been given to achieving ease of playing rather than to authenticity or harmonic fullness, but no harmonies have been changed. Occasionally the G-string note of a four-string chord has been eliminated, not only for ergonomic ease but also for aural clarity. Notes have only been removed from chords in those places where the removed note is not essential for the understanding of the harmony or of the voice-leading. Also, in quite a few doublestopped contrapuntal passages, the lower voice has been taken up an octave to avoid our low doublestops sounding like a hippopotamus duo (bars 27-30, 111-121, 140-143, 289-291 and 314-318) or simply to make the doublestops playable on the cello (bars 8-9 and their repeat at 296-297).

For anybody but the most accomplished cellists, the “Solo Version” is more of a curiosity than a concert piece. Even violinists have trouble making the chordal sections of this Fugue sound like they aren’t the soundtrack to an explorer hacking their path through a dense tropical forest and it is doubly difficult on the cello because of the size of our instrument. The Duo Versions are a much more successful (and user-friendly) way to play this piece.

There are two “Duo Versions” offered here: a “Low Version” (transposed down a fifth, like the solo cello version) and a “High Version”, a fifth higher (in the original violin key). In both “Duo Versions” the music is divided into a high voice and a low voice. The high voice is the “solo” voice and has most of the thematic, melodic material, while the low voice is the much simpler harmonic accompaniment with the occasional low register thematic material. These Duo Versions are very much “arrangements” rather than simple transcriptions because the lower voice (second cello part) has been filled out with additional harmony notes during the many monophonic passages so as to create a sort of “walking bass” to accompany the top voice.

The Low Duo Version is definitely the “Easier Version” of this fugue on the cello. The “High Duo Version” is perhaps even harder than the solo version (for the first cello part), because of the problems associated with Bach’s taking the music up as high as he ever takes the violin (to a G one tenth above the violin’s open E string in bar 263). Because we are playing in the original key, this means that we need to go up to G, almost two octaves above our open A string.

In both duo versions, it may be interesting for the second cello, in its doublestops, to try and reproduce the effect of the spread (arpeggiated) chords that are so characteristic of this music when played by only one solo instrument. When the second cello plays the notes of a doublestop together and strictly in time (on the beat,) this arpeggiated effect is sadly lost.

We have no possibility for page-turns during the four pages of music on which it lies. Some people nowadays play from a tablet, on which the page turns can be made with a foot pedal, but for those of us who haven’t become quite so modern, we will need to either memorise it (a gargantuan and risky task) or lay the music across two stands. It is easy to imagine Bach continuing the piece in an endless improvisation. We cellists on the other hand might be tempted to actually do the opposite, making an occasional cut in the enormous chordal passages perhaps, in order to make the piece more easily digestable.

- For Cello Solo: Edited Version

- For Cello Solo: Clean Version

- Literal Transcription

- Engraving Files (XML)

- For Cello Duo in Original Key (High): Study Score

- First Cello Part (Higher Voice)

- Second Cello Part (Lower Voice)

MOVT III: Largo

Here is a link to a video performance by Christian Tetzlaff (on the violin) of this transcendental movement:

Tetzlaff: Bach “Largo” from Sonata Nº 3

This movement lies very well for solo cello, with the only note changes necessary being the revoicing of a few chords.

Here is an audio of Christian Tetzlaff playing this movement in our cello key. Playing along with him is a lesson in music-making.

Approximately 40% of the quaver beats in this movement have at least one doublestop or chord on them, which makes it also a good candidate for playing as a cello duo. In our “Duo Versions,” the second cello has an accompanying voice, playing all the lower notes of the doublestops and chords as well as those other harmony notes that we have filled in where Bach left the harmony “empty”. The Duo Version in the “cello key” (transposed down a fifth) will thus also be our “Easier Version”. Playing this movement as a duo makes it so much easier that, as with many of the Duo Versions of movements of the Bach Unaccompanied Violin Partitas and Sonatas, we can play it now also in the original key (one fifth higher than the “cello versions”).

- Low Duo Version (down fifth): Unedited

- Low Duo Version Down fifth): Edited

MOVT IV: Allegro

This movement adapts very well to the cello. It has absolutely no doublestops or chords, which certainly helps for the adaptation process. No notes have needed to be changed from the violin version, although many bowings have been slightly modified to suit the cello better. Of the 1196 notes in this movement, 2 are quarter-notes, 24 are eighth-notes and the remaining 1170 (98%) are sixteenth-notes. This could easily produce the “sewing-machine effect” but doesn’t, thanks to Bach’s great variety of imaginative bowings and string-crossing effects. This movement goes as high as Bach ever takes us in his unaccompanied music: up to “C” on the A-string. It not only takes us up high, it also keeps us there for a good while of climactic high-register thumb-position scrubbing: a fitting climax for the final movement of his last Solo Sonata.