Syncopations and Offbeats For Cellists

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SYNCOPATIONS AND OFFBEATS

In syncopations, we don’t just play off the beat but also play over the beat in the sense that we tie our notes over the beats. Because of this, it is a good idea to work on our “offbeat” playing as a preliminary (preparatory) phase to working on syncopations. Simple metronomic exercises to establish the mathematical correctness of our offbeat and syncopated rhythms are a very dry (but efficient) first stage in getting familiar and comfortable with these types of rhythms. In the following exercise progression, the rhythms gradually “tighten” as we need to subdivide into increasingly smaller fractions (first two, then three then four).

Put the metronome on any pulse. This little series uses four beats to a bar but we could also do the same with three beats per bar. Play the progression first quite slowly, then gradually make the pulse faster. The difference between the simple offbeats and the syncopations is that in the syncopations, instead of playing short notes between the beats, now we will hold these notes until the next offbeat impulse:

SYNCOPATIONS

For a very pleasant next stage in acquiring fluidity and comfort in our syncopations, we could play music from the “popular” genres such as Ragtime and Pop. In this music, syncopations are normally much more common than in most “Classical” pieces and syncopated rhythms are often more common than four-square on-the beat rhythms.

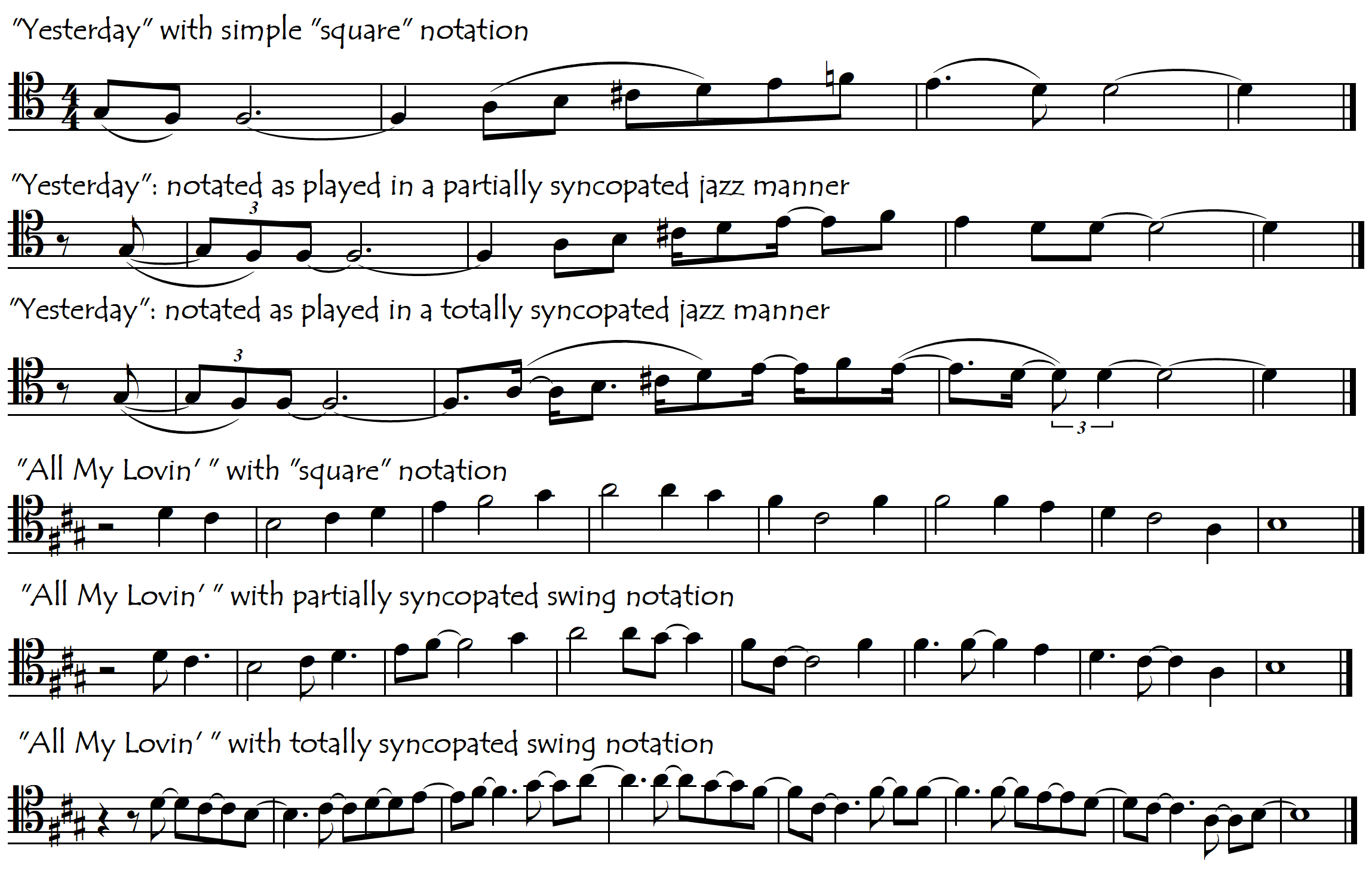

It might help to start with the “square” versions of a piece before moving on to progressively more syncopated versions. The following examples illustrate this progression with some songs by The Beatles:

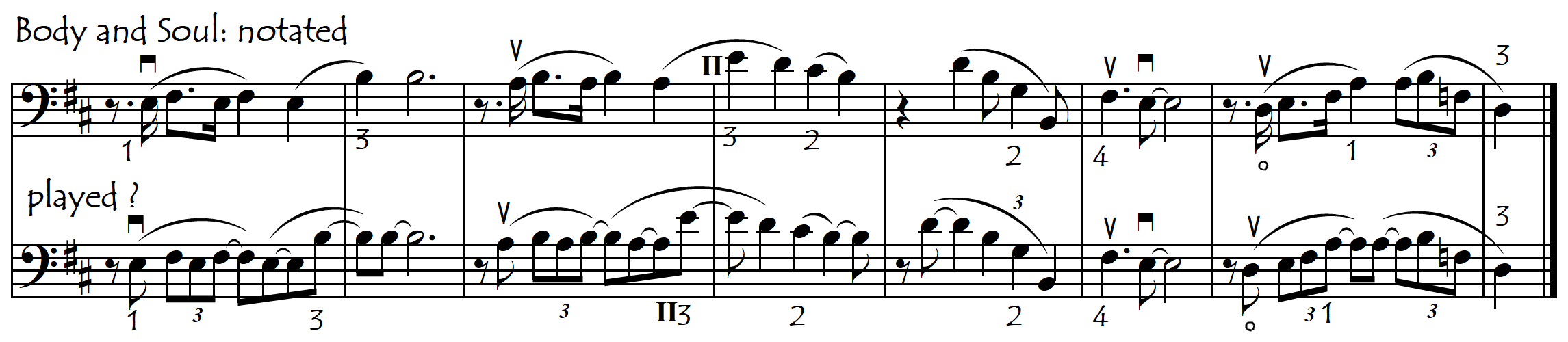

Jazz and Bossa Nova regularly take syncopation to another, higher, level of complexity and syncopated notes may here be even more frequent than notes that actually fall on the beats. Here is another musical example, this time taken from the jazz standard “Body and Soul” (1930) by Johnny Green.

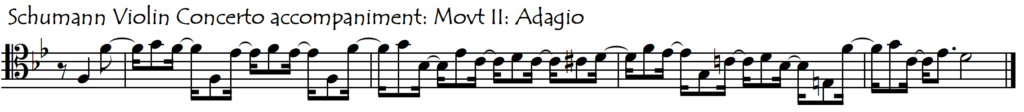

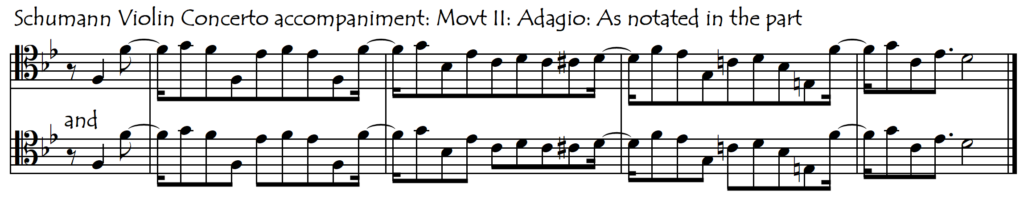

While the frequency of ties and syncopation reaches a maximum in “Popular” music, we will still encounter many complex syncopations in the more traditional “Classical” repertoire:

SOME FUN PIECES FOR WORKING ON FAST SYNCOPATIONS

1: BACH: COURANTE FROM HARPSICHORD SONATA Nº 6

With its constant use of (fast) syncopations in the right hand, we could rename the Courante from Bach’s Partita Nº 6 for Harpsichord BWV 830 (also used sometimes as the third movement of his Sonata for Violin and Harpsichord Nº 6 BWV 1019) as “Crazy Syncopations”. This piece is so attractive and entertaining with its ultra-fast light-footed syncopations, that we have transcribed it for cello as a very enjoyable “study” that can be used for working on this rhythmic skill. As well as offering it as a cello piece with a prerecorded accompaniment, it is also offered here as a duo for two cellos. This duo can be played asan “equal” duo in which both players take turns, alternating at the repeats between playing the syncopated “melody” line and the unsyncopated bass line. If one player prefers, they can of course play only (and always) the easier bass line (which has no syncopations).

Here below are two downloadable audios (computer-generated) of the accompaniment part “played” on the guitar. The first is a little slower than the second. If we actually download them then we can play them at different tempi. Because the accompaniment and cello start together, a one-bar introduction has been added as well as a few seconds of silence to allow us to sit down with the cello after pressing the start button. In these accompaniments, both repeats are made: we will almost certainly appreciate having a second opportunity for the many tricky passages !

2: GLIERE: SCHERZO FROM “8 DUOS FOR VIOLIN AND CELLO OP 39”

This is the seventh piece in the collection of duos Op 39. Both instruments are treated equally and both must play the fast tricky syncopated lines as well as the accompaniment. The piece is written in fast 3/4 time so when we look at the score/parts, instead of syncopations we see only hemiolas (with ties over the barlines) but this is just a trick of the notation. If it had been written in 6/8 time then the syncopations would have been more clearly “visible”. The score and parts are downloadable/printable from the following link:

Gliere: “Scherzo” from “8 Pieces for Violin and Cello”

See also “Fast Playing: The Importance of the Beat as a Coordination Aid”

THE EMOTIONAL SIGNIFICANCE OF SYNCOPATIONS

The emotional effects of syncopations are a lot like those of dotted rhythms. Fast “happy” syncopations (see the Bach and Gliere examples above) give incredible life, energy and bounce to the music and put a smile on our face whereas in their intense “darker” versions they can represent chaos and unresolved conflict. Slow gentle syncopations, in contrast, create a relaxed, laid-back, blurry, fuzzy effect of round contours and soft edges, giving a beautiful, cool, flowing expressivity and sentimental freedom to the music:

But at any speed, syncopations are the ultimate “antifascist” rhythms. Playing between the beats (rather than on the beats) is equivalent to writing between the lines. Syncopation is the opposite of “toeing the line”, of military discipline and clarity. How many military marches use syncopations ? None that I can think of. Imagine soldiers trying to march to war to the music of Bossa Nova, Jazz, Pop, Disco, The Beatles etc. Instead of striding forth with perfect order, discipline and determination, the soldiers would inevitably loosen up, dance, lose their aggressivity and end up having a picnic with the opposing forces!!! It’s not surprising that most “philosophical” music (music that searches for a deeper, more intimate humanity) such as Jazz, the Beatles, Schumann and other “Intimate Romantics”, Bossa Nova and even most Pop music, is full of syncopations.

And let’s not forget that we owe all this 20th-century syncopation -with all the joy and loosening-up that it brings – to the Afro-American influence. Scott Joplin, with his invention of Ragtime – a sort of fusion of African rhythms with classical harmony – planted the seed that would later develop into Big Band, Jazz, Pop, Rock, Rhythm-and-Blues, Bossa Nova etc and all of the most exciting musical developments of the 2oth-century.

SYNCOPATION NOTATION

We will often find syncopations noted in a way that can seem rhythmically confusing:

Rather than being frustrated with another example of user-unfriendly notation, we can look on the bright side, accepting that this type of code-deciphering keeps our brains sharp and may be one more reason why musicians seem to be protected against many forms of cognitive decline !