Cello Finger Articulation (and Release/Removal)

What is this movement of “finger articulation” that we are talking about here? The term “finger articulation” does not refer to the way in which we keep the string held down (see “pads or fingertips?” and “finger pressure“), but rather to the way (how and when) we place our fingers on the string. We will also look in this article at two other related questions: how we remove the fingers from the string, and whether or not to keep a finger down during a passage in which the same finger will be used at a later moment. Let’s look first at the placement of the fingers on the string.

FINGER PLACEMENT: WHEN? HOW?

There are many different ways of placing a finger onto a string. The differences concern not only the speed and timing of the placement but also the type of movement that we use to place the finger. Let’s look first at the types of movement that we can use to place a finger:

MINIMUM ESSENTIAL FINGER MOVEMENT OR ERGONOMIC HAND-ROLL ?

When we place or remove a higher finger we can choose to do the absolute minimum necessary movement (moving only the finger) or we can also incorporate a rolling movement of the hand to bring the finger towards (and away from) the string. This is not an either/or situation but is rather a question of degree: we choose how much (if any) of the rolling hand motion we want to use.

We have this choice at all articulation speeds.

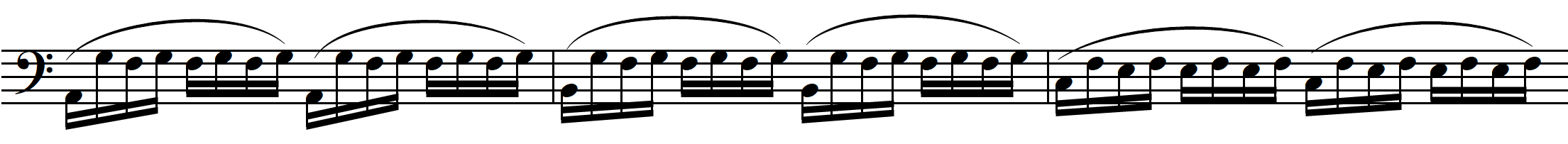

In fast playing, the use of the rolling hand movement relaxes our hand and prevents it from becoming wooden and rigid. Trills are the simplest example of this phenomenon but any fast finger sequence of consecutive neighbouring fingers can benefit from the hand-roll:

Here are links to some pages of exercises using this “hand-roll” in fast passages in one position in all the fingerboard regions:

THE ROLLING HAND, VIBRATO, DANCE AND AND DRAG QUEENS

In trills, we can easily observe just how similar the hand-roll movement is to the vibrato movement. We can even use trills as a way to learn vibrato. But the hand-roll is not only a useful ergonomic movement for fast articulations and vibrato. At slower articulation speeds (not trills) it is also an expressive, expansive, communicative gesture, almost like a little dance for the hand in which the degree of hand-roll reflects the intensity and characteristics of the music we are playing. We could almost consider it as a somewhat feminine characteristic, taken to its extreme in the exaggerated wrist movements of a drag queen, which is probably why some of the more macho cellists don’t use the hand-roll much outside of vibrato and trills !!

ARTICULATION TIMING: ON TIME OR ANTICIPATED?

Keyboard players simply articulate (press down) each new finger at the exact moment that they need the new note to sound but for string instruments the situation is quite different and the timing of our finger articulations is not always what we might automatically presume. Sometimes we have no choice but to place the finger exactly in the moment we need it: this requires an active, fast, energetic articulation. But at other times we can prepare the finger’s contact with the string, having it already lightly in place before we need to sound it. It is this timing of the finger placement on the string that very much determines the necessary articulation speed. Surprisingly, the only situation in which we absolutely must articulate the new finger exactly in/on time, is when we are playing a legato finger progression to a higher finger on the same string in the same position.

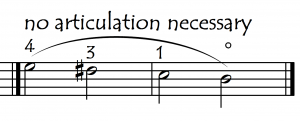

In the above examples we need to articulate the new fingers exactly “on time” – we cannot anticipate their placement – and therefore need to be very clear, precise, and fast with our finger articulations. When we talk about “finger articulation”, it is this type of pianistic movement to which we are referring. There are however very many circumstances in which we can anticipate the placement of a finger on the string and for which therefore we don’t need (or want) to do the articulation with a crisp, fast movement. Let’s look now at some of these situations:

ARTICULATION-ON-DEMAND OR LADY-IN-WAITING? THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HOW WE SOUND OUR HIGHER AND LOWER FINGERS

The higher the finger (using standard notation of thumb,1, 2, 3 and 4) the more it tends to be played by active finger articulation (in contrast to being played by the release of a higher finger). For example, the thumb never (?) needs to be articulated (hammered onto the string) in order to be played: once it is placed on the string it just stays there permanently, ready to be used when we need it. The first finger is only actively articulated after an open string or after notes played by the thumb: after any of the other (higher) fingers it is just there, waiting on the string just like the thumb (if we are using thumbposition). The second finger has to be articulated only after the open string, thumb and first finger notes: but after notes played with the third or fourth fingers it is just there waiting on the fingerboard. In order to sound (play) the top finger however, it almost always has to be actively articulated. The only finger after which it doesn’t need to be articulated is after itself!

Let’s look at some musical examples to illustrate this phenomenon by actually counting the number of active articulations used/required for each finger:

In “The Swan” by Saint Saens the first finger is actively articulated 4 times, the second finger 6 times, the third finger 16 times and the fourth finger 18 times. In contrast, 33 notes are played by a first finger that is already in contact with the string whereas only 9 notes are played by a fourth finger that is already in contact with the string. These types of proportions are repeated across the entire repertoire but are even more exaggerated in thumbposition passages because in thumbposition we basically never “articulate” the thumb.

In summary: the lower the finger, the more it tends to function as a “lady-in-waiting” and the higher the finger the more it tends to function with “articulation-on-demand”. Let’s look this in a little more detail now:

1. ANTICIPATION FOR LOWER FINGERS (THE” LADY-IN-WAITING”)

When the new note (finger) on the same string is a lower finger, it doesn’t need to be articulated because it is already on the string while the higher finger is playing. The lower fingers are thus sounded by the release (“negative articulation”) of the higher finger rather than by their own active articulation. It is easier to take a finger off the string than it is to place it on the string, which is why descending figures are easier for beginners than ascending figures.

2. ANTICIPATION FOR FINGERS ON A NEW STRING OR AFTER A SILENCE

When the new note is played on a different string (any finger), or if there is a silence between any two notes (fingers), we very often anticipate the finger articulation, placing the finger ahead of the bow and the rhythm. In the example below, the arrows refer to the approximate timing of the finger placement which, in these situations, can be anticipated (before the beat). This is actually easier to see when we play pizzicato, as pizzicato is less legato than bowed notes so we have more time between the notes to observe (and to do) our “anticipated finger articulations”.

The more separated the notes are, the easier it becomes to anticipate the placement of the fingers before their “correct” rhythmical moment (before we actually start to sound them with the bow or with a pizzicato pluck).

THE RELATIVE FREQUENCY OF ANTICIPATION COMPARED TO “ON-TIME” ARTICULATION

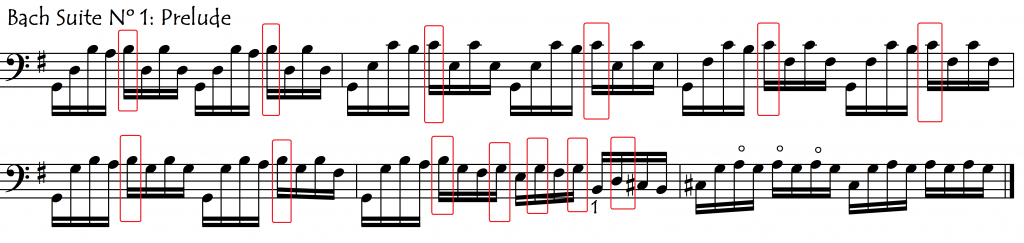

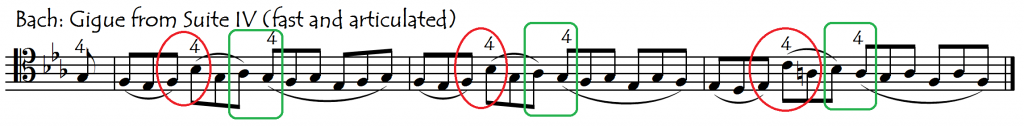

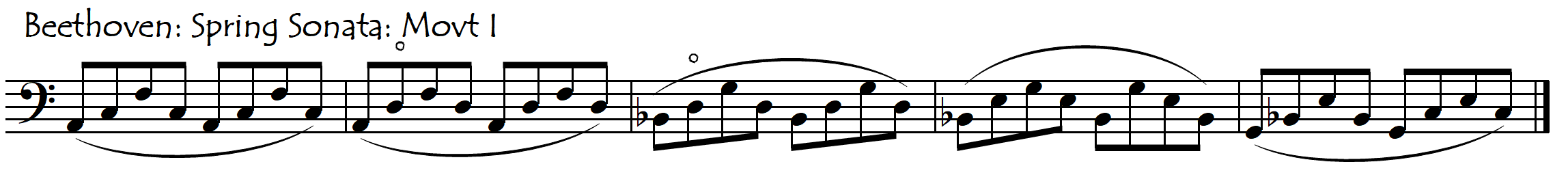

Anticipated finger placements are actually much more frequent than the energetic articulations. Look for example at the following excerpt in which the obligatory “on-time articulations” are shown within the rectangles.

Of the total of 70 stopped notes in this passage, only 14 (20%) actually require an “on-time” articulation. The other 56 notes (80%) can be placed anticipatedly. In the following example, none of the notes would normally be articulated “on-time” – all would be anticipated.

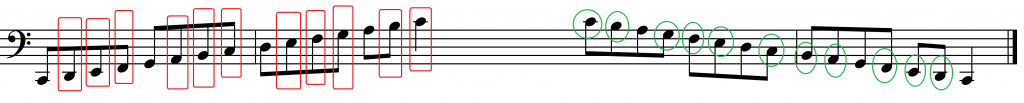

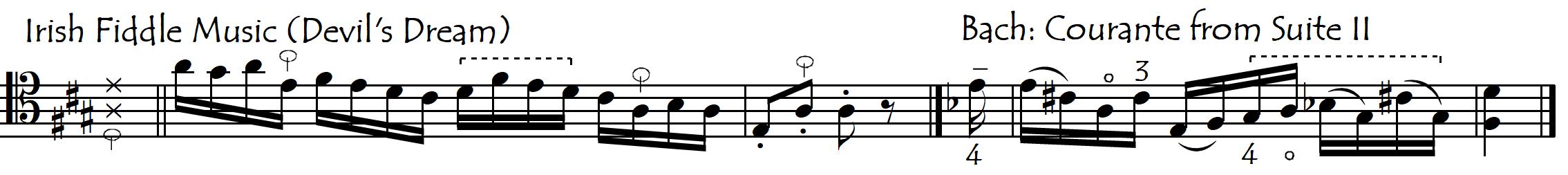

Not all musical excerpts have the same articulation characteristics. Look at the following examples. The “piano articulations” (where the note is “hammered” at exactly the required moment) are once again shown by the red rectangles. The “anticipated” finger placements (no hammered articulation required) are shown by the green enclosures.

The upward scale requires a hammered articulation on every stopped finger – but the downward scale requires absolutely none, as all the finger placements can be done anticipatedly. In the downward scale we could articulate the fourth finger on the new string if we wanted, but this is usually not useful, for reasons that will be explained just below.

ADVANTAGES OF ANTICIPATION

When we can do our finger articulations anticipatedly then we no longer need to articulate them hard or fast. In fact, an anticipated finger placement is basically the opposite of an “articulation”: articulating in advance not only allows us to place the fingers in a gentle manner, it actually requires us to use this gentle manner, as otherwise, the articulation will sound because of the percussive effect (see Left Hand Pizzicato).

Another advantage of anticipated placement is that we don’t need to coordinate this placement with anything – so long as we put the finger down before we need it, we can do it anytime we like. This is a beautiful, relaxed, easy feeling, and quite the opposite of the effort and difficulty involved in placing the new finger at its exact rhythmic moment and coordinating it simultaneously with a change of bow or change of string. (see Fast Playing and Anticipation Principle).

ADVANTAGES OF SIMULTANEOUS COORDINATED BOW/FINGER ARTICULATION

As usual, there are two sides to every story. While anticipation is usually good for smoothness and fluidity, there are also situations in which using a crisp, on-time articulation, even though not technically absolutely necessary, can be very helpful. We could also have named this section “disadvantages of anticipated articulation”.

1: DRAMA

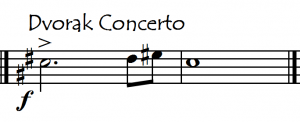

Accents, sforzandos, and dramatic fortes can all benefit from the decisiveness of a simultaneous attack from both hands. Having the finger already waiting calmly in position before the bow placement, takes energy away from the musical (and theatrical/choreographical)) drama: 2: SECURITY

2: SECURITY

A crisp on-time articulation can help give us security in our finger placements. This can be especially useful in shifts. It is as though the act of hitting the finger on the destination note gives us extra confidence to target/find that high note accurately and decisively in outer space. This is the opposite of groping smoothly around as though we were lost in a dark room. With an on-time articulation, we catch the note like a cat leaping for its prey: with a slow careful preparation followed by a sudden release of explosive energy. Some other useful analogies could be: swatting a fly, hammering a nail etc.

3. COORDINATION

Sometimes, articulating the finger on the new string to exactly coincide with the bow’s string crossing can help us to coordinate and control a fast slurred note sequence. It is as though the benefits of anticipation were here outweighed by the advantage of doing everything decisively, rhythmically, and all at once:

But what if the notes were slightly changed and the finger was already prepared on the lower string ???? We certainly wouldn’t “rearticulate” it ….. (see discussion at the bottom of the page about “rearticulation choices”).

4. RELAXATION

With a finger placed on the string, our left hand is not as relaxed as when it has no fingers placed. As a general rule, we should use every possibility we can find to allow the hand to relax. Placing the fingers too early – especially if we also start pressing too early – causes tension. Tension means danger. We must not anticipate too early nor too decisively. The best anticipation is both as late as possible and as light as possible. Otherwise we might actually be better off by not anticipating our finger placement!

ARTICULATION TIMING IN SHIFTS ON THE SAME STRING

Same-finger shifts require no new finger articulation. Assisted shifts downwards, and scale/arpeggio-type shifts upwards also have no need for a new finger articulation because they go to a lower finger (which is normally already in contact with the string). The only shifts that require a new finger articulation are upwards assisted shifts and downwards scale/arpeggio-type shifts because, in both cases, they require the placement of a higher finger. Let’s look at these now:

SHIFTING TO A HIGHER FINGER: PLACE NEW FINGER EARLY, OR ARTICULATE IT EXACTLY ON TIME?

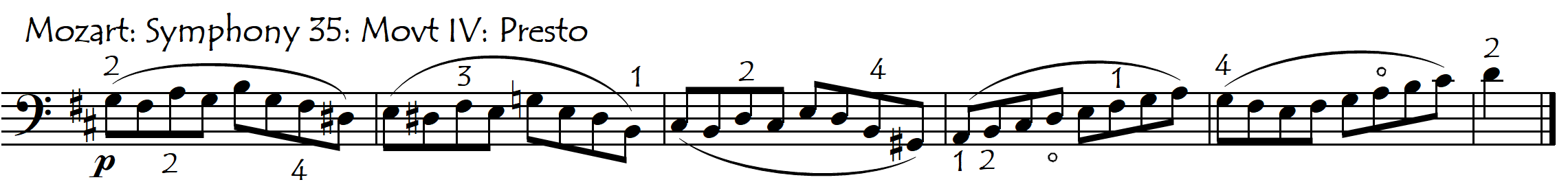

This is a very important – and conflictive – question! When we shift to a higher finger – either on the same string or onto a new string and both upwards and downwards – we can choose when to articulate the new (higher) finger. Either we do it clearly and crisply in the exact moment that we want to hear the new note or, on the contrary, we place the new finger both imperceptibly and anticipatedly and thus slide into the new note on the new finger. This applies to both “assisted shifts” upwards (red circles) as well as to “scale/arpeggio-type” shifts downwards (green rectangles) as can be seen in the following example.

Sometimes our decision (choice) is based on technical reasons: with an anticipated finger articulation we can hear the shift glissando on the new finger. But at other times this is a stylistic choice, between a vocal style (legato, lyrical) or a pianistic one (clear, articulated, no glissando). In the above example, every placement of the fourth finger gives us an opportunity for choosing between these two alternatives. Being a smooth legato melody, with all the shifts under slurs, the optimum conditions are present for favouring a choice of smooth anticipated articulations in the shifts (although many cellists might play it with strong rapid articulations for clarity). But what about the following example?

Here, we are in a different musical world. Now, the shifts coincide not only with bow changes but also with the strong rhythmical accents. These are the optimum conditions for a strong rhythmic finger articulation of the higher finger after the shift, rather than the smooth anticipated placement during the shift. While we don’t need to do this crisp articulation, doing it actually fits in with the accented, energetic musical character.

The speed of the passage is also an important factor in our decision as to when (and how strongly) to articulate the higher finger in a shift. Slower passages are more suitable for the vocal, legato, smooth, anticipated placement whereas faster passages can appreciate more the clarity and definition of a crisp rhythmic (exactly on-time) placement. Play the following examples both slowly and quickly to see how the articulation needs of the shifts change according to the speed of the passage:

What the right hand is doing also affects our decision about when (and how strongly) to articulate the higher finger in a shift. In the following example, the exact same notes, with the exact same fingerings, will be played completely differently (from the point of view of the finger articulation) according to the desired right-hand (bowing) articulation. When the shift coincides with a right-hand articulation (as in the first two bars) our shifts will also be articulated whereas when the shift occurs on a slur (as in the last two bars) we are more likely to want to do a smooth sliding glissando:

These are choices between complete opposites – night and day, black and white, (but definitely not between “good” and “bad”). It is either one or the other, with no possibility of compromise (finding a mid-point). We could almost characterise these two options as representing two very different psychological prototypes: the “Puritan” way (highly articulated, with absolute clarity) and the “Sensuous” way (very smooth, with the notes merging into one another). We need to be able to do (and be?) both ……

But there is another factor that will also influence our choice in this question: whether or not we can actually hear our glissandi. When playing in large orchestras – or in any noisy situation in which we can’t clearly hear our glissando shifts – the articulated rhythmic placement of the new finger after a shift becomes an intonation life-saver. Lacking the audible glissandi feedback to tell us where we are (relative positional sense) we now depend on our absolute positional sense: our ability to find any note “out of the blue” (without any reference to the note which came before it). Absolute positional sense is helped very much by the vigorous, decisive articulation of the target finger in each new position (see Positional Sense).

Having looked at the subject of finger-placement timing, let’s look now at the other possible characteristics (variables) of our finger placements.

ARTICULATION SPEED AND ENERGY:

According to the musical situation, our appropriate left-hand articulation speed can vary between, at the one extreme, the almost imperceptible padding (steps) of a cat creeping stealthily towards its prey, and – at the other extreme – the rapid fire explosions of automatic gunfire, a pneumatic drill, a string of firecrackers exploding in a row etc. These wildly different possibilities are actually very similar to the different ways in which we make contact with our bow on the string (bow trajectory from the air): we can place it on the string very slowly, gently and imperceptibly or, at the other extreme, we can hit it hard and fast into the string to make a sfz. This is why the term “articulation” can be applied to both the left and right hands.

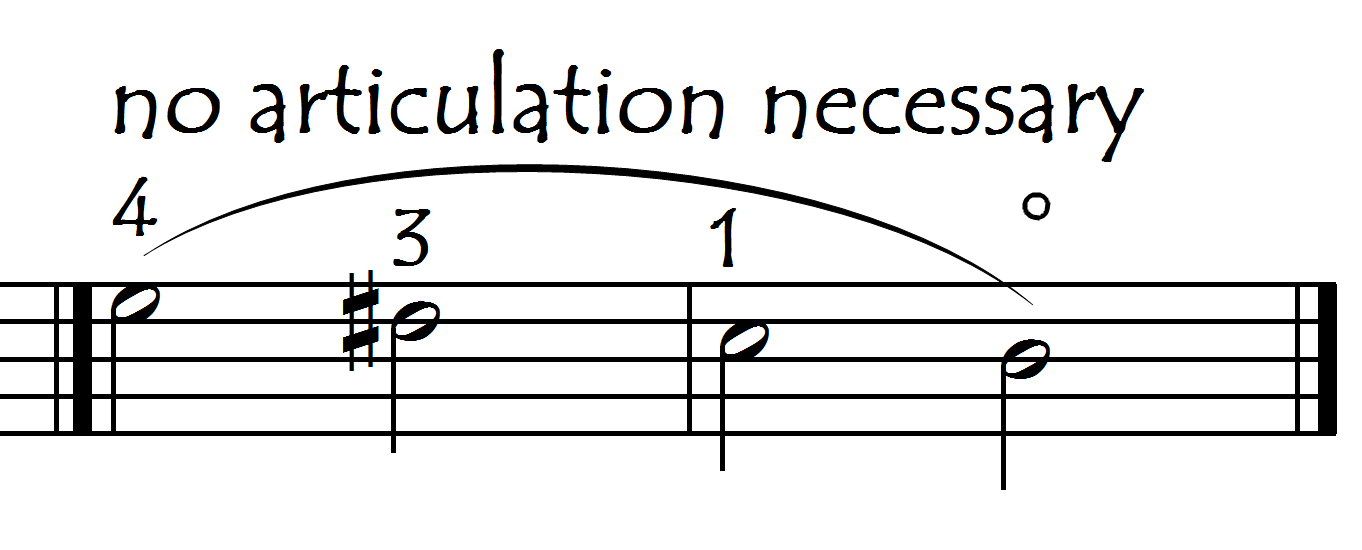

In slower, gentle, lyrical music not only do we not need hard, fast finger articulations, we in fact need to avoid them, as they can disturb the musical expression. Here we really do want to just be sliding (gliding, slithering) around as in the following example:

In faster music however, in order to help the notes “speak” clearly from their very beginning, it usually helps to use faster, clearer, crisper (more energetic) finger articulations than in slow lyrical playing. We can often hear very clearly this energetic articulation (hammering) in closely-miked recordings (in which the microphone was placed close to the cello) such as in this recording of Stephen Isserlis playing the Bach Suites (extracts). This is definitely not a catwalk.

Energetic articulation comes quite naturally in loud fast passages but we often have to remind ourselves to use it also in fast soft passages. Hitting the fingers hard on the fingerboard while we are playing very lightly with the bow feels quite unnatural. This really requires practice (see Fast Playing).

Articulating a new note requires more work (speed x pressure) than just maintaining any one note which is why our hand tires much faster when we are playing many notes than when we are just holding long notes. But the force and energy required to articulate the new notes is not only determined by musical factors. The more resistant the string is, the greater the energy required to stop a new finger. This means not only that the thicker lower strings need more articulation energy, but also that the higher the strings are from the fingerboard the harder they will be to articulate rapidly.

FINGER RELEASE: WHEN? HOW? “REVERSE” ARTICULATION = LEFT HAND PIZZICATO

It is not only how we make contact with the string that is interesting but also how we break that contact. How and when we release the fingers from the string is an important (and often neglected) aspect of our finger-string contact investigation.

When we use a lower finger after a higher finger, we don’t need to articulate that new (lower) finger because it is already in contact with the string during the preceding note.

However, in order to help the lower note to sound cleanly from the very beginning, it will normally be a good idea to do a left-hand pizzicato (pluck of the string) with the higher finger as we release it from the string. This L.H. pizzicato is basically a “reverse articulation”: instead of placing the lower finger energetically and quickly on the string, we are now removing the higher finger energetically and fast. But whereas the “hammered” placement is made in a purely vertical direction (the finger whacks down onto the string from directly above it), our energetic removal is done with a strong horizontal (sideways) component in order to be able to pluck the string. This LH pizzicato produces almost the same effect for the lower finger as if we were to place it with a “hammered” articulation. It is also a very useful trick to help the bowed open string to sound cleanly and clearly right from the beginning.

Try any downward scale with and without these left hand pizzicato “reverse articulation” effects. In the following example, the + sign indicates that the note is sounded by the vigorous removal of the previous (higher) finger from the string with an energetic plucking (LH pizz) movement. Try this first with only the left hand (no bow or right-hand pizzicato):

“Playing” (sounding) notes and passages without the right hand obliges us to use exclusively our two left-hand articulation possibilities: both “reverse” (LH pizz) and “hammering/whacking”. This gives us an intense left-hand articulation workout. But even when we are using the right hand to sound the notes, the technique of releasing the fingers with a horizontal “pluck” rather than just a simple vertical release is still a very useful basic component of our fundamental cellistic toolkit that can be used at all times.

Here are some specific exercises for working on this horizontal pluck-release, firstly to the lower fingers, and then to the open string:

Horizontal Pluck-Release To the Lower Fingers: EXERCISES

Horizontal Pluck-Release To the Open String: EXERCISES

The subject of left hand pizzicato (horizontal pluck release and “whacks”) is dealt with in great detail on its own dedicated page where you can find all these exercises and more.

RELEASE AND REARTICULATE, OR KEEP IT DOWN ? CHOICES FOR REPLAYING THE SAME FINGER IN MULTI-STRING AND SINGLE-STRING PASSAGES

Normally we release a finger once we have started playing a different note with another finger. But at many other times, we have the choice as to whether or not we leave a finger “down” (on the string) while playing with other fingers:

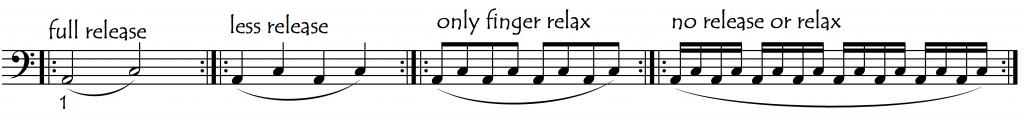

We must choose what to do with the finger before reusing it. We can choose between the two opposite extremes of:

- keeping it pressed down

- releasing it entirely (lifting it off the string and then rearticulating it when we need it)

Or we can make a compromise between these two opposites, by releasing the finger pressure but still keeping the “released” finger permanently in contact with the string and thus perfectly ready for its next intervention. This tends to be a very useful compromise as it avoids the real danger of the hand becoming tense and rigid, which is what can easily happen when we maintain more than one finger stopping the strings at the same time.

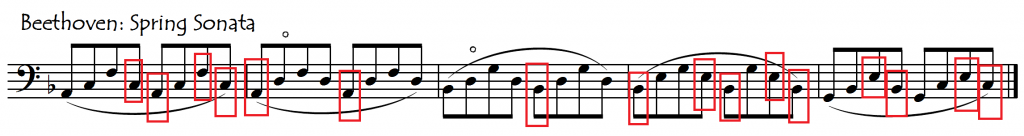

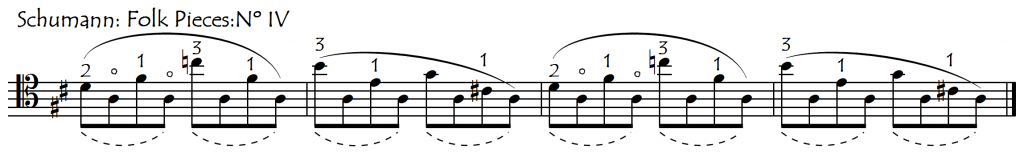

Here below is the identical passage, but this time all the notes for which we have these different articulation possibilities are shown inside the rectangles. All of these notes can be played in any of three different ways:

- no rearticulation (permanently stopped)

- rearticulated completely

- compromise (rearticulated but without any loss of string contact beforehand)

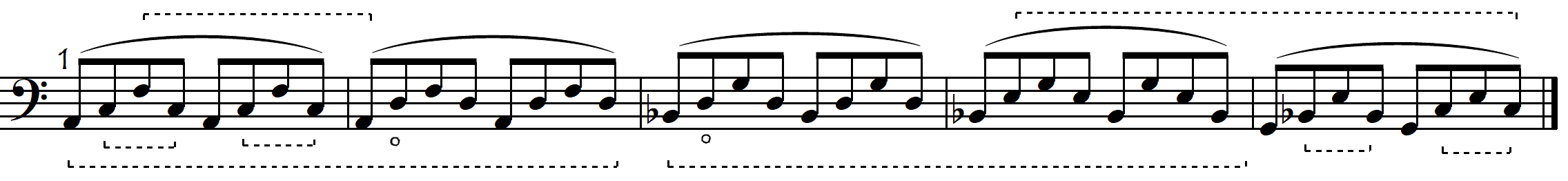

Because these decisions are such an important part of our finger choreography, it is useful to have a sign that indicates “keep the finger contact” (either stopped firmly or just gently touching). In the cellofun.eu editions the dotted bracket is used to indicate this. Don’t confuse this sign with the solid bracket, which indicates that a finger is stopped on two strings at the same time (see Capo Fifths) !! The following example shows all of the possibilities for keeping finger contact during the Spring Sonata passage. Playing it slowly, we soon realise (especially in the first bar) that if we were to keep all those fingers down that don’t absolutely need to be removed, then our hand would be too stuck to the strings and the advantages of maintaining finger contact become lost.

Of course, our choice as to whether or not we release a finger entirely between its interventions will be very much influenced by the speed of the passage. The less time we have between reutilisations of the same finger, the more difficult (and impractical) it will be to release the finger pressure and rearticulate the finger. This concept applies equally well to passages on one string as it does to multi-string passages:

But the amount of time we have between utilisations of the same finger is not just a direct function of the speed of the passage. Even in a very fast passage, if the time between the original finger placement and its rearticulation is sufficient, we can still release it entirely while it is not in use:

Here are two more examples in which we will almost certainly be well advised to “keep the finger down”, perhaps with a release of pressure.

The following link opens a compilation of similar repertoire excerpts in which this same technique can be very useful:

Keep Finger Down: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

ARTICULATION AFTER AN OPEN STRING

After an open string, the work of articulating a finger (stopping the string) is more difficult than when we articulate a finger after a lower finger. This added difficulty is due to the fact that the open string is higher off the fingerboard than it is when stopped by a finger, so our new finger has to push it a greater distance to the fingerboard. This can pose problems in two different situations:

- in fast passages

- in slurred passages

In slurred passages we might be tempted to hit the new finger down hard and fast in order to avoid a “squeak” (the note after the open string not sounding cleanly because of the distance it must be pushed before it is properly stopped) but this impact can make the string move so fast and so far that it causes our bow to shudder and bounce on the string. This is especially a problem in the Intermediate Fingerboard region because it is there that the strings are the highest above the fingerboard. It is also especially a problem in the middle of the bow (the bounciest part) which is why in the following excerpt we might want to break the long slurs and play everything in the upper half of the bow (where it bounces much less or not at all).

In fast passages, the extra articulation and speed required after an open string can make our fingers get in a tangle:

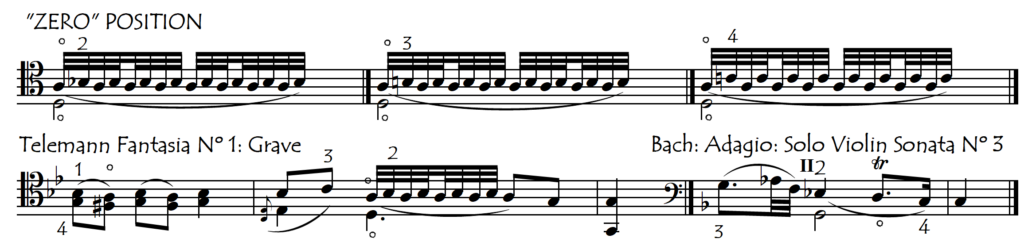

Trilling on an open string is the ultimate example of this problem. To give our hand more stability we can use “zero position” in which the first finger is placed on the nut at the top of the fingerboard (by the scroll):